Now that my two weeks of research at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives are finished (thanks to the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation), it’s time to address an issue that often comes up when the Hall’s discussed. It’s not one that relates to my visit, but I sometimes get asked about it all the same, even though I don’t have a formal relationship with the Hall. Which is: why aren’t some rock artists in the Hall of Fame? Who should be in it who isn’t already?

First off, I should note that I don’t vote in the Hall of Fame elections (and haven’t been asked to). Of more importance, it’s my feeling that musical passions are subjective enough that it’s impossible to apply objective, or even somewhat objective, criteria to an award like this. If someone isn’t in the Hall of Fame whom you really like, what matters most is that they’re in your Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It shouldn’t cause distress if other people haven’t voted them in yet.

Still, sometimes I’m lobbied to sign petitions for some artists to get into the Hall. I don’t remember all of them offhand, but I know Doug Sahm and Roky Erickson were two. Those are cultish artists who are frankly a longshot to get in soon or at all. But it’s not just hip underground types that are being championed — at one of my presentations, I was asked why Connie Francis wasn’t in.

I certainly wouldn’t mind if Sahm and Erickson made it (and don’t think Francis should be in there), but really, you’d have to build another wing or two to accommodate everyone in my personal Rock Hall of Fame. They’d include at least a few hundred bands and solo artists who aren’t in yet, and the Hall isn’t going to induct that many new honorees in the next few years (or, most likely, in my lifetime). That’s not even counting all the producers and vital non-musicians who rate consideration.

For what it’s worth, I do have opinions on my favorite acts who aren’t in yet. What follows is a list of the ten artists I’d most like to see in the Hall. I took into consideration their quality, longevity, and impact on the whole of rock. Let me be upfront, however: this is a very subjective list, guided by my personal tastes, not one which tries to take into account how many fans musicians have, how many records they sold, and how critics regard them. It’s what I like, not a consensus of what everyone likes. My personal Hall of Fame, even if the adjunct is only in my mind.

Rated in rough order of preference, here we go:

1. Love. One of the great folk-rock bands of the mid-1960s, Love generated one of the all- time classic rock albums with their third LP, Forever Changes. That record has performed better on critics’ all-time best-of lists that almost any other, and their first two albums, though not on the same level, had their share of good-to-greatness too.

I don’t know if the Hall of Fame’s voters and nominators sit around discussing fine points of qualification, like many fans and sportswriters do for the baseball Hall of Fame. If they do, however, my guess would be the major strikes against Love are that their peak was brief — just those three albums, in 1966-67 — and their commercial success was limited, though they did have two small national hits with “My Little Red Book” and “7 and 7 Is.” I do feel — though some fans vociferously disagree with me — that Love’s quality fell off drastically after Forever Changes, and that none of their subsequent records (on which principal singer-songwriter Arthur Lee was the only remaining member from their mid-‘60s heyday) were very good or distinctive, let alone on the same plane as their mid-‘60s work.

But that mid-‘60s work was brilliant — and certainly, especially in the case of Forever Changes, influential. And not just on cult artists of subsequent decades — ask Robert Plant. Cult artists haven’t fared too well in Hall of Fame voting, but some groups with limited commercial success have gotten in, like the Velvet Underground and the Stooges. If there’s room for them, there should be room for Love.

As to which members of Love should be inducted, that will be even more of an imbroglio than other disputes over inductees from bands with multiple lineups. Even in the course of their first three albums, Love had seven members. I’d go with the five guys on Forever Changes (Lee, guitarist/next-most-important songwriter Bryan MacLean, guitarist Johnny Echols, bassist Ken Forssi, and drummer Michael Stuart), perhaps adding Snoopy Pfisterer, who played drums and keyboards on their first two albums. I wouldn’t take in anyone from the post-Forever Changes lineups save Lee.

2. The Zombies. One of the great British Invasion groups, ranking near the very top of the tier once you get beyond the best half-dozen or so (the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Who, Yardbirds, Kinks, and Animals). And besides the Beatles and maybe the Beach Boys, the most inventive melodicists of their time, especially in their use of minor keys.

The Zombies have gained considerably in popularity among critics and fans in the past decade or two. It’s a little mysterious that they’ve been passed over so far, especially since lead singer Colin Blunstone and keyboardist Rod Argent are keeping the flame burning with regular and pretty well-received touring. My guess is that there might still be a perception — an unfair one, but one that is held by some listeners — that their impact was limited to their three big hits: “She’s Not There,” “Tell Her No,” and “Time of the Season.” One friend (not a voter) even insisted to me that having heard those three songs when he was growing up, he felt no need to investigate the rest of their catalog.

But the point is that the Zombies had a lot of other good songs in their catalog, even if none of their other singles made the Top Forty, and many of them bombed commercially. Not only that, those singles (and some of their LP cuts) were quite diverse. And at the end of their career, they did prove capable of making a strong album that expanded their lyrical parameters beyond melancholy romance, Odessey and Oracle.

It probably shouldn’t sway nominators and voters one way or the other, but all of the Zombies save guitarist Paul Atkinson are still alive, and would likely be very appreciative of an induction while they have their health. Unusually, there will be no controversy as to who should be inducted — during their 1964-68 lifetime, the Zombies were the quintet of Blunstone, Argent, Atkinson, bassist Chris White, and drummer Hugh Grundy, with no personnel changes.

3. Them. Like the Zombies, a band that ranks just below the top half-dozen British Invasion bands in quality and originality. Plus they had a future star in their ranks, singer Van Morrison, who also wrote their original material in the two-and-a-half years or so he was in the group.

The problem Them faces, I would surmise, is that their peak was brief, and their commercial success even a bit less extensive than the Zombies’. It’s really the explosive 1964-66 R&B/rock recordings with Morrison that matter, though they did hang on for four more LPs in the late 1960s and early 1970s with Van-less lineups. They had just four hit singles of varying degrees, none of which made the US Top Twenty: “Here Comes the Night,” “Mystic Eyes,” “Gloria,” and “Baby Please Don’t Go.”

A couple of these were much bigger in the UK (“Baby Please Don’t Go” hitting the Top Ten and “Here Comes the Night” soaring all the way to #2), but great UK popularity hasn’t seemed to manage much to the Hall, overall a pretty US-centered institution. Though I wouldn’t buy this argument, it might also be contended that since Van Morrison’s already in the Hall, there’s no need to induct Them, which he fronted for a small if significant part of his lengthy career.

But Them’s legacy, even limited to the Morrison years, isn’t really all that slim. There are about 50 tracks, many of them superb. Their impact was greater than their chart performance, even in the US, where many musicians were fervid Them fans, from the Doors and Iggy Pop to Byrds bassist Chris Hillman. Plus they did the original version of one of the all-time, and most-covered, rock standards with “Gloria.”

Do they deserve their own, separate induction? Yes. Will it happen? Probably not, perhaps in part because, even by the volatile standards of who to induct and who not, the process of selection for Them will be a nightmare. Bassist Alan Henderson is the only guy who was in all their lineups, and even during Morrison’s time with the band, there were a dozen or so lineup changes (even the estimates of how many lineups there were varies according to the source). I’d go with Morrison, Henderson, original guitarist Billy Harrison, and Harrison’s replacement Jim Armstrong — though leaving out a drummer is problematic (I’d go with John McAuley), as is leaving out a keyboardist (I’d go with Peter Bardens, though he wasn’t in the band too long), especially as spooky organs were a big feature of Them’s distinctive sound.

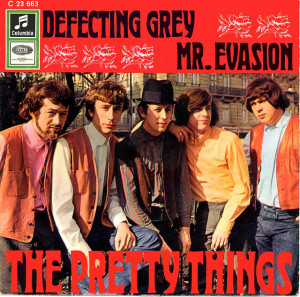

4. The Pretty Things. Let’s be honest here — these guys aren’t going to get in, at least during my lifetime, unless the usual criteria for selection radically change, or the Hall radically expands in size. But they should get in. It’s almost a cliche to state this by now, but the Pretty Things were the best British band of the ‘60s not to have a hit in the US. It’s almost as much of a cliche — but true — to note that at their outset, they were very much like the Rolling Stones (and Pretties guitarist Dick Taylor had even been in the Stones in 1962), but rawer. They also evolved into an important psychedelic group, and recorded one of the first rock concept albums, S.F. Sorrow (1968), whose release predated Tommy by about six months.

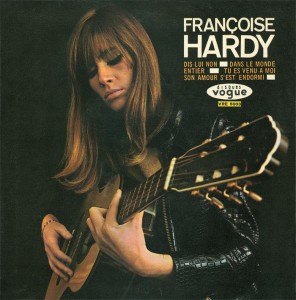

A pioneering psychedelic single by the Pretty Things, even if it pictures a previous lineup than the one that recorded these tracks.

What works against the Pretty Things? Well, though they’re way, way better known now than they were in the 1960s, they’re still not very well known in the US. Even in the UK, their commercial success wasn’t that great, and mostly experienced near the very beginning of their career, when “Honey I Need” and “Don’t Bring Me Down” were British Top Twenty hits, and their debut album did well. There are few rock bands that inspire as passionate cult devotion as the Pretty Things, and justifiably so. But the fact is, most Americans still don’t know who they are — and even many knowledgeable rock fans and critics who’d like them, given half a chance, don’t know much about them, and have heard little of their work.

Electing the Pretty Things would strike a great blow for honor based on quality, rather than the usual yardsticks of sales and fame. Deciding who to induct would be the usual challenge. Singer Phil May, who’s been on the ride almost all along, is a no-brainer, as is guitarist Dick Taylor, who was there for all their finest ‘60s work. The other guys in the quintet that made their early recordings (bassist John Stax, drummer Viv Prince, and rhythm guitarist Brian Pendleton) should probably get in too. But so too should other members who figured strongly in their recordings later in the ‘60s — drummer Skip Alan, multi-instrumentalist Wally Waller, keyboardist Jon Povey, and probably even drummer Twink, who played on S.F. Sorrow. I don’t feel passionate about putting in various other guys who played on post-S.F. Sorrow albums.

5. The Moody Blues. Now here’s a band that not only stands a fair chance of getting in, but has had armies of fans knocking on the door for quite a while. It’s not a secret that the Moody Blues are among the most popular of artists not currently in the Hall. In polls asking rock listeners which acts should be inducted, the Moodies regularly score near or at the top.

So why aren’t they included? The Moody Blues did not fare especially well among critics, although the albums during their 1968-1973 commercial prime were huge sellers, and included some fair-sized hit singles. To many, they epitomized the pretentious pomp of progressive rock; to some more serious underground aficionados, they were too twee and pop to stand comparison with more experimental prog rockers. Art-rock in general hasn’t fared that great among Hall voters, perhaps in part because of its dominance by UK acts; although Genesis made it, Yes, for instance, are still waiting, in spite of their huge global popularity.

But for me, the Moody Blues have a strong case based on their 1964-1968 recordings alone. Few fans know much about their pre-Days of Future Passed recordings aside from their one mid-‘60s hit, “Go Now.” But their mid-‘60s British Invasion-era discs — featuring future Wings-man Denny Laine as lead singer, guitarist, and (with keyboardist Mike Pinder) co-songwriter — are quite strong, with a haunting R&B/pop feel quite distinct from their peers. While Days of Future Passed introduced some of the bloat and bombast they’ve been lambasted for, it was one of the first notable quasi-concept rock albums, and (when the orchestral passages took a break) had some genuinely fine, soaring rock songs. Their albums got steadily less impressive from that point onward in my view, but made their mark as some of the most popular progressive rock LPs of their day, even if they leaned toward the poppiest and most romantic side of that spectrum.

It seems like only a matter of time for the Moody Blues — but then again, people have been saying that for about twenty years. There will be no dispute that the quintet on their late 1960s/early 1970s recordings (original Moodies Mike Pinder, drummer Graeme Edge, and singer/flautist Ray Thomas, as well as guitarist-singers Justin Hayward and John Lodge) should be on the plaque. But look forward to lively arguments as to whether to include Denny Laine (whom I would say absolutely has to be part of it), though it’s likely few will care whether the bassist in their mid-‘60s lineup, Clint Warwick, will be part of the discussion.

6. Fairport Convention. There are a number of acts, I think, who would undoubtedly be in Rock Hall if it was based in London and the music’s history was approached from a British perspective. Cliff Richard, the Shadows, the Jam/Paul Weller, T. Rex/Marc Bolan, the Smiths, Kate Bush, and others all would have been in for quite some time if that were the case. That’s fodder for a different article, but Fairport Convention are another band I think would have been enshrined long ago. Their importance to the British strain of folk-rock looms larger than any other artist’s does, and some might even contend the style wouldn’t exist without them.

But in the US, Fairport were never big sellers. Not that they were huge sellers in the UK either, but (like their early peers Pentangle, another band deserving of consideration), they always had a much bigger presence in the British scene, on the charts and otherwise. On their US tours, they were more bill-fillers or support acts than headliners. They’re another act that have a white-hot US cult following, but the great majority of US citizens still remain largely or wholly unfamiliar with them, historical importance be damned.

This is just speculation, but if Fairport ever got far in the nominating process, there might be genuine concern over the uncertainty over which members to induct. They shifted personnel so often that their style changed quite substantially as well, from the West Coast folk-rock-influenced tone of their early records to the staunch rocked-up traditional British folk approach they’d settled into by the early 1970s. That style’s much less to my taste than their earlier efforts, but they’d deserve a place in the pantheon for their four late-‘60s LPs alone.

If it was up to me (it isn’t), I’d make sure to include the quintet from their second and best album: singer Sandy Denny (who deserves strong consideration for induction as a solo artist), bassist Ashley Hutchings, drummer Martin Lamble, singer Iain Matthews, and guitarist Richard Thompson. I’d also include original woman singer Judy Dyble and the three Daves who were crucial in their shift to more traditional British folk — drummer Dave Mattacks, fiddler Dave Swarbrick, and bassist Dave Pegg. There have been a number of other musicians in this still-active band, but those are really the names that matter, even to the majority of Fairport fanatics.

7. Mary Wells. Motown stars have done pretty well in the Hall voting, so it’s another mystery to me as to why Wells hasn’t gotten in the door. She had a good number of good-to-great hits in 1960-64, including one of the label’s biggest, 1964’s chart-topping “My Guy.” At that point — which has often been forgotten — she was Motown’s biggest star. It was also at that point, unfortunately, that she left the label, never to recapture much commercial success.

If I can draw a loose parallel to the baseball Hall of Fame for a moment, perhaps Wells’s case has suffered because there’s a wide disparity between what some baseball experts would call her “peak value” and the rest of her career. There are numerous ballplayers who perform at a superstar level for three or four years, but whose case for Hall induction suffers by the relative ordinariness of the rest of their time in the big leagues. Wells performed at a superstar or near-superstar level — commercially and, much more importantly, artistically — for such a period of time. She made some fair records during the rest of the ‘60s for other labels, but was really just another soul singer after leaving Motown, in part because she was no longer produced by Smokey Robinson, who also wrote her best material.

Yet the best records Wells made while at Motown — and there were quite a few good ones, not just the hit singles — were really good. Her voice has been criticized by some historians as lacking when compared to dynamos like Gladys Knight, but for me, personality’s always mattered much more than conventional lungpower. And Wells had vocal personality galore, projecting shy sexiness better than almost anyone.

Mary’s prospects for Hall of Fame induction have also likely been hurt by the lowering of her profile since her death almost 25 years ago, and the absence (to my knowledge) of a strong campaign on her behalf. While her career itself was not cut short by death, we have to wonder what might have been had she stayed at Motown and continued to work with Robinson. Had that been the way things played out, there’s probably no doubt she would have been in the Hall a long time ago.

8. Link Wray. While it seems ridiculous to categorize such an innovative early rock’n’roll guitarist as a one-hit wonder, it has to be remembered that most fans have heard just one song by Link Wray: “Rumble.” As much as that classic did to pioneer the imaginative use of electronic distortion, it’s hardly all there is to his legacy. He recorded many great instrumental records in the late 1950s and early 1960s; in fact, he was quite prolific. Not all of his releases were great, of course, but he had a higher batting average than most pre-Beatles rockers, including some in the Hall of Fame.

And he wasn’t just all weird and wacky effects, using the guitar in many manners of thrilling ways, often with original material. Not that Duane Eddy and the Ventures don’t deserve their plaques, but I’d rank Wray way ahead of them, and he was certainly way more fearlessly experimental. The raw, often savagely wild power of those late-‘50s-to-mid-’60s records is the foundation of his case, but he also made some good vocal roots rock discs in the early 1970s, if far lower-key ones.

Wray’s influence on at least one much more famous guitarist is unquestioned, Pete Townshend testifying to it in liner notes he wrote for one of Link’s releases. He has far fewer hit records than the few other primary instrumental acts in the Hall, however, and I’d guess he has to be considered a longshot for induction anytime soon.

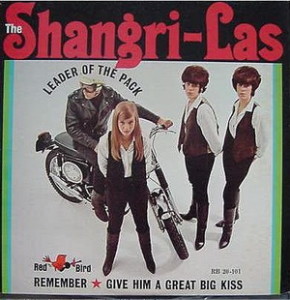

9. The Shangri-Las. One of the greatest girl groups, the Shangri-Las also had some huge hits, particularly “Leader of the Pack.” I’d wager their short career has worked against them in Hall voting, however. There were only three other big singles (“Remember (Walking in the Sand),” “I Can Never Go Home Anymore,” and “Give Him a Great Big Kiss”), and they were really only strongly in the public consciousness for a year and a half or so in 1964 and 1965. Like Wells, they were hurt with the loss of their support team at their label, in their case when Red Bird Records went out of business in 1966.

Although Betty Weiss was part of the original Shangri-Las, by the time of the photo on this release, they were down to the trio of her sister Mary Weiss and identical twins Marge and Mary Ann Ganser.

That brief recording career, however, was enough to produce more great records than many acts manage in two decades, let alone two years. And not just the hits mentioned above — “Past, Present and Future” was an amazing mid-charter, “Dressed in Black” a phenomenal B-side, and “He Cried” and “Out in the Streets” also possessed of great drama. Some of their other tracks were merely good or okay, but a Shangri-Las compilation (virtually everything they did can more or less fit on one CD) makes for much stronger listening than most single-artist girl group anthologies.

As archetypes of fetching teenage angst, the Shangri-Las could not be beat. Sadly, the Ganser twins who comprised half the group are not around now. But lead singer Mary Weiss is, and having upped her public profile drastically in recent years, one imagines she’d be very pleased to accept the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame honor.

10. Scott Walker. Like the Pretty Things, don’t let this listing get your pulse racing too fast — he’s never going to get in, not unless the very nature of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame changes. There aren’t many other figures in popular music, however, who’ve made such a heavy mark with two quite different styles — one as a pop-rock balladeer (and quite a good one) as lead singer of the Walker Brothers, and the other as an increasingly serious, almost arty singer-songwriter and interpreter as a solo artist, especially in his early career. That’s not even counting his way-avant-garde excursions from the late ‘70s onward — not ones to my taste, but efforts that are wholly uncompromising, and have an avid if specialized cult of their own.

Walker did have some US hits as part of the Walker Brothers, but he really isn’t all that familiar a figure Stateside, even though he was born and raised in the country. The Walker Brothers, though all were American (and none were brothers, or even named Walker), were much, much bigger in the UK in the mid-‘60s than the US, briefly inciting teen adulation almost on the level of Beatlemania. Scott had some British hit singles and albums in the late ’60 after leaving the Walker Brothers, but they were virtually unheard in the US. Like the Pretty Things, he’s much, much better known (speaking of his work as a solo artist) in the States now than then. But all those Mojo magazine huzzahs notwithstanding, he’s still very much a cult, if a pretty large one.

If his profile ever raised to the point where his induction was seriously considered, his style might work against his success. To some listeners, he’s far more a pop singer than a rock one, especially in his late-‘60s/early-‘70s records. To me, he’s enough of a rock singer to make such distinctions unimportant. To take the point just a little farther, if a singer like Bobby Darin’s in the Hall (he is, and made a lot of discs that were as much or more pop than rock), Scott Walker is certainly “rock” enough too.

Here’s one consolation to any rock voters or nominators feeling pangs of guilt. Though Walker’s alive and in good health, he — unlike most of the quality artists not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame — almost certainly does not care whether he gets in or not, having made clear his disdain for the usual trimmings of industry success for many years now.

************************************************************************

There’s my Top Ten of sorts. Remember, again, that I’ve never been involved in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame nomination or election process, or been approached to do so. So arguing these choices, or lobbying for others, will not have an effect on who gets selected. This is just a personal list.

There were many names who also received strong consideration, and just missed the cutoff. Sandy Denny, as mentioned in the Fairport listing, was one, as the greatest British folk-rock singer. Robert Wyatt, who’s had a lengthier career in more “underground” genres than almost anyone, was another, and someone else who likely would have been in the Hall had it been administered from a British perspective. John Mayall’s records were uneven (though often very good) and often overshadowed by his star guitarists Eric Clapton, Peter Green, and Mick Taylor, but there is hardly any other figure as influential in helping to launch significant careers, and for helping to ignite the British blues-rock explosion in general. I’d like to see Francoise Hardy in the Hall, not only for her excellence during much of her first decade as a recording artist as a singer and songwriter, but as a step toward “internationalizing” the Hall beyond performers from English-speaking countries. She’s likely the longest shot of any artist mentioned so far.

My books, and lists on my website, give you a good idea of some of the other artists I’d like to see in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (as I keep saying, there are many). Maybe I’ll go through numbers 11-20 in a subsequent post. I’ll end by just listing a few other favorite artists who seem to me to have very strong cases:

Nick Drake; Procol Harum; Jonathan Richman/The Modern Lovers; the Marvelettes; Tim Buckley; the Collins Kids; Harry Nilsson; the Beau Brummels; Bobby Fuller; Lesley Gore; Jackie DeShannon; Big Brother & the Holding Company; Pentangle; the Soft Machine; the Troggs; Judy Collins; the Move; Nico; John Cale; Doug Sahm/The Sir Douglas Quintet; the Searchers; Marianne Faithfull; Phil Ochs; Free; King Crimson; Irma Thomas; Dick Dale; the Spencer Davis Group; Arthur Alexander; Barbara Lewis; Jan & Dean; the Outsiders (the Dutch ’60s group); Dionne Warwick; Mike Bloomfield; the Paul Butterfield Blues Band; the Wailers (the reggae group); Johnny Kidd; Nina Simone; Ian & Sylvia

Blues artists (as influences on rock): Junior Wells; Otis Rush; Sonny Boy Williamson; Slim Harpo; Bukka White

Country artist (as influence on rock): The Delmore Brothers; Patsy Cline

Jazz artists (as influence on rock): Dizzy Gillespie; Lionel Hampton; Slim Gaillard; Wes Montgomery; Mose Allison

Folk artist (as influence on rock): John Fahey

Producers/Engineers/Songwriters/Managers/Label Owners/Journalists: Joe Meek; Lee Hazlewood; Giorgio Gomelsky; Shel Talmy; Paul Rothchild; Jimmy Miller; Joe Boyd; Tom Wilson; Tony Visconti; Norman Whitfield; Peter Asher; Mickie Most; Burt Bacharach & Hal David; Bob Johnston; Norman Petty; Bert Berns; Fred Foster; Norman Smith; Geoff Emerick; Chet Helms; Estelle Axton; Carol Kaye; Lillian Roxon; Graham Gouldman; Nicky Hopkins; Pete Frame; Paul Williams (the Crawdaddy founder, not the singer/songwriter); Shadow Morton