There are still plenty of album reissues and music films that interest me, but there are a deluge of music history books in comparison. There are so many that there are at least a half dozen or so such 2023 books I’d like to check out eventually, but I ran out of time. I’m sure there are others from 2023 I’m not yet even aware of that I’ll read in the future. At least my #1 choice was clear-cut, though there were plenty of other fine or at least somewhat worthwhile volumes.

The supplementary list of 2022 books I didn’t read until 2023 is pretty long, running to a dozen titles. I know my way of making annual lists is different than some and perhaps many other writers, who are strict in only considering releases from one calendar year. My feeling is that I’d rather cover deserving books late than never, especially considering that some would have placed quite high on my main 2022 list had I read them in time, and that some are not going to get wide attention. My feeling is also that just because a certain amount of time has passed between a release and a review doesn’t mean it’s any less worth reading, as much as some publicists would like for reviews to only appear at the time (or even before) a book is released.

Without trying to pat myself on the back too much, also keep in mind that unlike many listmakers, I don’t post mine until the final days of the year, instead of in early December, November, or even earlier. I know this happens because some publishers insist on having these lists compiled on earlier deadlines, and that there’s often a belief that they have to be made in time for holiday or even Black Friday shopping. But not everyone builds their shopping around these times, and not everyone celebrates these holidays. Of more importance, I’m always able to fit in a few more books, records, and films on my lists by writing about those I come across in November and December, instead of relegating them to perpetual absence from annual lists.

1. Nick Drake: The Life, by Richard Morton Jack (Hachette). Drake only gave a couple scanty interviews during his brief life, and information about the British folk-rock singer-songwriter has been on the fairly scarce and contradictory side. That hasn’t stopped there being a few previous books about him. This one far surpasses those in depth, and is a superb biography by any standard, even leaving aside the challenges of piecing together the life of a man about whom even some basic facts have been shrouded in mystery. The comprehensiveness of the research is astounding, and not only for the lengthy interviews conducted with his closest surviving associates, those being producer Joe Boyd, engineer John Wood, and sister Gabrielle Drake. Morton Jack tracked down dozens of others, from school friends who’d never previously spoken on the record to publicists, journalists, Island Records staff (including label head Chris Blackwell), and other musicians amateur and professional. He also draws from many other sources, some quite obscure, going to the heroic extent of tracking down a piece in which Drake was interviewed for the UK magazine Jackie, though for many years it was thought he’d only been interviewed in one article (in Sounds).

Beyond the sheer wealth of information, however, the author also pieced together both his musical career and complicated, troubled personal life with critical acuity and perceptive sensitivity. All of Drake’s three albums, as well as the considerable amount of material taped but not issued during his lifetime (including his mother’s recordings of her compositions), are expertly described and contextualized. Some long-standing mini-myths are punctured along the way, such as him dropping off a tape of Pink Moon in Island’s office without a word (he actually gave it to Blackwell personally); his second album, Bryter Layter, coming out in late 1970 (actually it was delayed a few months until early 1971, causing Drake considerable distress); Drake seldom performing (actually he did a few dozen concerts); and Nick never receiving critical praise while alive (actually there were quite a few good reviews, including some in the US and even one in Penthouse, though these didn’t translate to big sales at the time).

Drake’s extremely withdrawn personality, and his decline into mental illness and 1974 suicide at the age of 26, presents a greater challenge to document. Fortunately Drake’s father Rodney kept a diary during this time, and Morton Jack had access to this and other letters. While the family’s struggles in the last three years of Nick’s life don’t always make for a pleasant tale, this difficult time is relayed with objective detail and empathy for a situation that his parents and friends handled as best they could, but were ultimately helpless to alleviate. Some rare, sometimes previously unpublished photos and documents help round out the story in a 500-page book that’s far more info-packed and authoritative than anyone would have thought possible.

In accordance with full disclosure, I note that I read a draft of the book before it was published, and gave the author detailed comments. I also interviewed him about the volume at a July 2023 bookstore event, and you can read the transcript here. This biography would certainly have earned the same place on this list, however, had I not been slightly involved or known the author.

2. All the Leaves Are Brown: How the Mamas & the Papas Came Together and Broke Apart, by Scott G. Shea (Backbeat). The Mamas and the Papas had been covered extensively in books before this overall history came out, including in the autobiographies of Michelle and John Phillips; a biography of Cass Elliot; and Go Where You Gonna Go: The Oral History of the Mamas & the Papas. All of those have value, but this is the first really comprehensive biography of the group as a whole, and the best of the lot. It not only ties together a lot of the strands addressed partially in other books, but also adds quite a bit of additional info not likely to be found elsewhere. The numerous pre-Mamas/Papas outfits in which the members served time are all documented, and the music of the actual band intelligently and objectively discussed. So are the Monterey Pop Festival that John Phillips and their producer Lou Adler co-organized, and the brief ascendance of Scott McKenzie with the Phillips-written “San Francisco.” In contrast to the approach of many biographies, their much duller years after their 1968 split—both solo and together (including their 1971 reunion album)—are only given as much space as needed, which is to say, not very much.

As for their volatile internal relationships and squabbles, as well as their drug use and temper tantrums, those are here too, as they can’t be wholly separated from the music they made and the songs (largely written by John Phillips) they composed. They don’t overshadow the music, with specific tracks discussed in depth, and detailed examination of how they were produced and arranged. What’s perhaps only striking in retrospect is how much their oft-ebullient and joyous music contrasted with very troubled personal lives, and how brief their creative peak was—about a year and a half—before Phillips’s songwriting declined and they passed out of fashion, not long after they were at folk-rock’s cutting edge. Phillips comes in for both much praise for his musical abilities (at least during that brief peak) and criticism for his personal behavior, which echoed beyond the grave when his daughter Mackenzie publicly stated she and her father had sexual relations.

3. I’m Into Something Good: My Life Managing 10cc, Herman’s Hermits & Many More!, by Harvey Lisberg with Charlie Thomas (Omnibus Press). Unlike Brian Epstein, Andrew Oldham, and Allen Klein, Harvey Lisberg is not a name known to most British ‘60s rock fans, though he was a peer of and interacted with them to various degrees during the British Invasion’s heyday. He’s not even as well known as some managers from that scene lower on the totem pole of public recognition, like Giorgio Gomelsky. But he was very successful, and if he didn’t have any clients other than Herman’s Hermits and (starting in the 1970s) 10cc who made big and long-range impacts, they did very well by him. And though 10cc, and certainly Herman’s Hermits, don’t have the critical clout of clients like the Beatles, Rolling Stones, and the Yardbirds, their stories are pretty interesting. Lisberg played a big role in popularizing both bands, and has a lot of good anecdotes about them and some others in this fun and well written memoir. It’s not huge, but it doesn’t need to be, telling the tale with economic wit, and not getting too caught up in personal or non-musical detours that don’t carry nearly as much interest as the stars at the center.

If Herman’s Hermits’ catalog doesn’t command enormous critical respect (and Lisberg doesn’t blow up their importance any more than it deserves), he has good, interesting insights into how they quickly became international stars after he began working with them. Despite their squeaky clean image, not everything was smooth sailing. They had to replace their rhythm section when Mickie Most agreed to produce them; they started to resent Most for not being able to play on all their own records or have as much artistic self-determination as they wished; and Allen Klein was lurking in hopes of moving into their affairs, though he was fended off for the most part. Lisberg began working with 10cc’s Graham Gouldman long before 10cc started, and the reports of how Gouldman developed a reputation as a songwriter of hits for the Yardbirds and Hollies are also of high value, and not without their quirks – rather absurdly, it was hoped the Beatles might record Gouldman’s “For Your Love” before it found a home with the group supporting the Beatles on a 1964 Christmas bill, the Yardbirds.

Gouldman, Lisberg, and the other members of 10cc realized the importance of constructing and running their own Strawberry Studios before realizing they should form a group of their own to work there. This wasn’t just a notable signpost in their growth; by the standards of the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was very progressive to have an artist-run studio in Manchester, at a time when the British recording scene was heavily dominated by London. Lisberg had some less durable, and sometime passing, associations with artists like Julie Driscoll, Andrew Webber and Tim Rice, and Barclay James Harvest, and these are relayed without more space than they merit, though they’re also well worth reading.

4. Happy Trails: Andrew Lauder’s Charmed Life and High Times in the Record Business, by Andrew Lauder and Mick Houghton (White Rabbit). Like Harvey Lisberg’s, Andrew Lauder’s name might not be too well known to the average rock fan, even less so in the US than the UK. But as an A&R man (and sometimes working in other capacities) in the British music business since the late 1960s, he worked with an astonishing variety of interesting artists. None of the UK or German artists he was instrumental in helping to get record deals and/or building their careers became big in US, with the exception of Elvis Costello, with whom he didn’t work with as closely as most of the others with whom he was involved. You might also count Jeff Lynne, who was part of the Idle Race, one of the first acts championed by Lauder at his long stint at the UK branch of Liberty Records, though Lynne moved on to the Move and Electric Light Orchestra.

Yet the list is quite impressive and eclectic, including Hawkwind, the Bonzo Dog Band, Dr. Feelgood, Buzzcocks, the Groundhogs, Nick Lowe, Man, and then up through the late 1980s and early 1990s with the Stone Roses. He was also key to bringing German 1970s rock to international attention (even if the acts never rose to more than a cult level in the US) with Can, Neu!, and Amon Düül II. He worked on the UK end of careers of American performers like the Flamin’ Groovies, Buddy Guy, Canned Heat, and John Lee Hooker. All of these artists are discussed with inside (though seldom scandalous) and entertaining info, Lauder also bringing zeal to his memories of cult figures who never even made the dent that the likes of Neu! did, such as post-punkers the Pop Group and early-‘70s progressive rockers High Tide. The stunt of flying a planeload of journalists and hangers-on to Brinsley Schwarz’s legendary hype-ridden appearance at the Fillmore East is covered in detail, though the rest of their time as a band is respectfully noted too.

The ups and downs (though in Lauder’s case, it was mostly ups) of working within the volatile music business are likewise documented with detail. Andrew moved on from Liberty to Radar, (briefly) Island, Demon/Edsel, and Silvertone. While his recollections of deciding what to reissue and how well the releases sold on Edsel might be regarded as too specialized by some, for record nerds the nitty gritty of how compilations by the likes of the Action and reissues of cult acts like the 13th Floor Elevators were arranged are fascinating. Some of the cold machinations and personal conflicts at various labels are also interesting, and though Lauder seemed to avoid the worst of these, certainly his frustrations at Island Records put that label and its chief Chris Blackwell in a poorer light than is usually reported. The worst foibles of the bands he interacted closely with are given far less sensationalism than many memoirs would, though they do come into play at times, Lauder remembering how a member of the Flamin’ Groovies would blast the Rolling Stones’ “Tumbling Dice” repeatedly in the wee hours while staying with Andrew in London.

Reading this, you can’t help but wonder at how much the business has changed since Lauder literally wandered into a publishing company in London as a teenager and was offered a job on the spot, starting his climb up the ladder. His post-Stone Roses activities are kind of rushed through in a few pages, but that’s fine, as his interest in being a player in the record world was diminishing, though his passion for music never has. It encompassed a remarkably wide field, from progressive rock to blues and Krautrock to post-punk and catalog reissues. Lauder treats each genre with equal devotion, without prioritizing the bigger commercial successes as more significant.

5. The Island Book of Records 1959-68, edited by Neil Storey (Manchester University Press). From a purely visual point of view, and to a large degree just for the information it contains, this nearly 400-page coffee table book is stunning. Covering the first decade of Island Records’ existence, it does indeed focus on the records the label issued, though there’s lot of history of the company. Starting with its considerable attributes, there are reproductions of most of the covers of the LPs it issued during this era, many quite rare, often adding back covers, inner labels, and non-UK editions. There are also lots of photos of the artists, reproductions of ads from the period, Island-related documents like press releases and tape boxes, and other memorabilia.

There are also many extensive quotes, drawn both from interviews done for this project and plenty of other sources, some dating back to when the records were made. Oriented toward interesting anecdotes, these add up to an oral history that’s a book in itself. They feature memories from those involved in founding and running the company, especially its main executive, Chris Blackwell; numerous artists who were on the label; and ancillary figures with something interesting to pitch in, including photographers of the LP covers, producers, and recording engineers. While most of the first half or so of the book focuses on the ska and reggae upon which Island was initially built, there’s much coverage of the rock it moved into in the mid-1960s. Traffic in particular get a lot of space, including plenty of pages on their legendary cottage in the British countryside.

While early Island releases by some other celebrated artists like Fairport Convention, Jethro Tull, and John Martyn are noted in detail, refreshingly, quite a few of the less renowned Island acts receive a good share of attention too. These include Spooky Tooth (dating back to their initial incarnation as Art), Nirvana, Wynder K. Frogg, and jazz musician Harold MacNair. Although the first artists with whom Blackwell had success, Millie Small and the Spencer Davis Group, actually had their big hits licensed to Fontana Records, as Island was able to repackage some of their material, they’re also detailed at length. There are also entries, though understandably shorter ones, for Island’s flops and odd records where no one can quite remember why they were green-lighted. There’s even a section on their “adult” line and rugby discs, which weren’t notable aesthetic accomplishments, but played a big part in keeping the label afloat.

For all its assets, the text could have been better assembled. When some of the figures are first quoted, there aren’t parenthetical notes identifying their role in Island, although brief bios are given in an appendix. This and some of the sequencing can sometimes make it harder to follow than it could have been with that additional context. Some of the quotes are on the mundane, technical, or list-heavy side and could have been more tightly edited. It could be contended that more attention could have been paid to Island’s singles, although there’s a lengthy discography of those in an appendix, and there were so many that giving all of them detailed entries would have expanded the book to an unpublishable size. Still, there were some interesting acts who only had singles or EPs on Island, including the Smoke, the Anglos, and Chris Farlowe. And there are a good number of typos throughout the book – hardly a rarity in music book publishing, unfortunately, but there are more here than in most such productions. It’s to be hoped the next volume, which will only cover the years 1969 and 1970, won’t have as many.

Here’s a mistake that might never be pointed out anywhere else, for what it’s worth. On page 171, in the multi-page entry for The Best of Millie Small, there’s a picture of the Rolling Stones with a young woman on the cover of a March 1964 issue of Pop Weekly. There’s no caption, so one assumes this was placed here because it was thought the woman with the Stones is Millie Small. It isn’t. It’s Cleo Sylvestre, whom the Stones backed on a 1964 single produced by their manager at the time, Andrew Oldham.

6. But Will You Love Me Tomorrow? An Oral History of the ‘60s Girl Groups, by Laura Flam and Emily Sieu Liebowitz (Hachette). The authors interviewed more than a hundred singers, songwriters, producers, and associates for this book, as well as using a good number of quotes from other sources when figures were dead or unavailable. While this doesn’t uncover a great deal of basic info that wasn’t already known, there are many stories about the songs, the records, and the oft-fraught business side and internal relations in the girl group scene. The emphasis is very much on the top acts, and most of this is devoted to those – the Shirelles, the Ronettes, the Crystals, the Shangri-Las, the Chantels, the Dixie Cups, the Chiffons, the Supremes, Martha & the Vandellas, and the Marvelettes, with a little on the Exciters, the Cookies, the Angels, and others. That’s still enough to fill more than 400 pages, and get into some fairly little known stories like the Cookies singing backup vocals on the Chiffons’ “One Fine Day,” and Little Eva’s “The Locomotion” originally being intended for Dee Dee Sharp.

The quotes are sometimes gossipy in nature, and occasionally go into observations about the music business of the era and early days of rock’n’roll that aren’t tightly related to the girl group subject. Note also that this doesn’t cover the numerous fine solo artists who sang in the girl group style, like Mary Wells and Lesley Gore, or some of the actual groups who made good records, like the biggest one-shot of the whole genre, the Jaynetts’ “Sally Go ‘Round the Roses.” There’s a little too much space at the end on reunions and post-‘70s oldies touring, and for the likely small minority that cares, it would be good to have the sources of the quotes that weren’t from first-hand interviews noted. These are minor flaws in an overall useful addition to girl group literature, and one that details some of the darkest sides of the story. The failure of many of the artists to get their just royalties isn’t so unknown, but there were also rapes of a couple girl group stars; frequent falling-outs that ended close friendships in many of the groups; and, for Estelle Bennett of the Ronettes, struggles with mental illness and homelessness.

7. Time Has Come Today: Rock and Roll Diaries 1967-2007, by Harold Bronson (Trouser Press Books). Rhino Records co-founder Harold Bronson has written a couple previous books based around his former business and associated activities, The Rhino Records Story and the more specialized, anecdote-driven My British Invasion. There’s some inevitable overlap between topics covered in those and this volume, which puts many of his experiences in a chronologically ordered diary format. It’s still pretty entertaining whether you’ve read the others or not, tracing his journey from high school music fan to preeminent label reissue executive, getting to meet many of the interesting characters in all levels of the music (and sometimes general entertainment) business along the way. These go all the way from the Beatles down to a down-and-out Sky Saxon, and even some of the stories relating to stars are unfamiliar, like Bronson getting the scoop from Andrew Oldham as to why the Rolling Stones’ Big Hits album had a different version of “Time Is On My Side” than the hit single. Oldham told Bronson he didn’t remember being asked before, though Harold brought it up decades after the tracks were recorded.

Peter Noone, the Monkees, the Standells, Blondie, the Pretty Things, Arthur Lee and Love, the Yardbirds, the Music Machine, and obscure names known only to collectors like the Autographs – Bronson has stories about all of them and dozens of others, often detailing conversations (and brush-offs) that caught them more off-guard then they usually were. He got to interview some of them, as well as some acts he and not too many others were terribly interested in—which generate some amusing stories that are more interesting than their then-current records—as a rock journalist in the 1970s before concentrating on Rhino. There might be a little more than necessary about his semi-pro, humor-oriented bands in the early years, but the focus is on other personalities. Which are sometimes more disagreeable than some fans want to hear, as when Paul Rothchild dismisses his attempt to interview him about working with Love because the producer thought a reissue compilation wouldn’t sell, or Jeff Beck declining to authorize a Yardbirds BBC compilation.

An aspect to these reflections that might be more subtle, but is also striking, is Bronson often dealt with figures who were on the downside of their career, or way past the point where they were even involved in making records. As a young writer in the ‘70s, he often spoke with people who had been stars, but were just a few years past their peak work, though they weren’t so past their primes that they weren’t still figuring on getting back to the highest level. Some who were long past their hits—sometimes just one or two hit singles—still were under the impression they were just another hit record away from getting right back in the game. Some had kept physically fit; others had gone to waste. Bronson treats them respectfully without making undue fun of their delusions or conditions, but they’re still sobering reminders of how the stretches in which musicians are famous and at their most artistically productive are often short.

8. Leon Russell: The Master of Space and Time’s Journey Through Rock & Roll History, by Bill Janovitz (Hachette). I admit I’m not especially a fan of Russell’s records, even from his brief period as a big star in the early 1970s. But Russell’s life is of interest to almost anyone with a serious passion for rock history, owing to his collaborations with many artists and his substantial achievements as a ‘60s Hollywood session man and arranger. This 500 plus-pager has loads of research and detail on all phases of his colorful, sometimes volatile career and life, though the bulk of it is on his most significant years as a recording artist, from around the late 1960s to the mid-1970s. Maybe some of the minuter detail could have been pared down about his various homes and family relationships. Sections on his post-‘70s/pre-final years, when he largely toiled in obscurity in small venues and many meager records, can be tougher to navigate, though the author acknowledges the shortcomings of much of Russell’s work during this rough stretch. Russell’s descent from stardom was bumpier than most, and his resurgence in the 21st century (largely engineered by Elton John) among the more unexpected music comebacks, and that unnerving path is meticulously documented here.

The book doesn’t unduly dwell on the fallow period, however, though it doesn’t pull punches as to his stormy artistic and personal interactions There’s plenty about his slow rise from session player and arranger (most successfully on hits by Gary Lewis & the Playboys) to making his own records, combining multiple roots styles and more. There’s a lot about his most celebrated guest appearances and concerts, particularly on Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour, and the Concert for Bangladesh, and his work with Delaney & Bonnie. There’s also quite a bit about Les Blank’s early-‘70s documentary film on Russell, unreleased for many years due to Leon’s objections, though it became available shortly before Russell’s death.

9. David Bowie Rainbow Man: 1967-1980, by Jérôme Soligny (Monoray). While there’s no shortage of Bowie biographies and reference books, this stands out for its sheer length (almost 700 pages) and a different approach than most other major Bowie volumes. Soligny focuses on extended quotes from interviews, most though not all done by the author, with a great many people who worked with Bowie. This includes major figures like producers Tony Visconti and Ken Scott, the Spiders from Mars, and side musicians like Carlos Alomar. There are, perhaps even more valuably, memories from many who haven’t been extensively interviewed, including significant figures like Hermione Farthingale, Bowie’s late-‘60s girlfriend who was part of a trio with him and John Hutchinson (who’s also interviewed). And there are quite a few interviews with much more obscure figures with more peripheral but interesting relationships, usually working rather than personal ones, with Bowie. These include sleeve designers, photographers, recording engineers and technicians, and musicians who just played with him a bit on record and/or on stage.

It’s true some key colleagues’ voices are missing, like Brian Eno, Angie Bowie, and manager Tony Defries (see the comment from the book’s author on this post for a note on those). He spoke with a great many others, however, usually in pretty recent times (the 2010s). Some of the stories clear up or actually contradict stories and incidents long reported as fact. Some of them might disappoint those who enjoy some of the more mythical ones. Singer Antonia Maass contended, for instance, that the lyrics to “Heroes,” long reported to be based on a meeting by the Berlin Wall between her and Visconti, were written before they started their affair. The oral histories are linked by commentary from the author about each of the albums Bowie recorded between 1967 and 1980, and together with extensive footnotes, they provide the basis for separate chapters organized around each album. His pre-1967 work is also discussed, as are some singles and side projects (particularly his work with Iggy Pop) not contained on the albums.

Inevitably there’s some overlap between the extensive info here and what you can find in other Bowie tomes—which, given the length of this book, are likely to have been read by many who read this volume. The reason this doesn’t rank higher, however, is that Soligny’s prose can be overly grandiose, and the oral histories often extol Bowie’s virtues to an extreme degree, though there’s room for some (not many) controversial or negative views. The footnotes are also too numerous and often too extraneously detailed, though as they’re separated into sections of their own at the end of each chapter, they don’t interrupt the text as much as they could have.

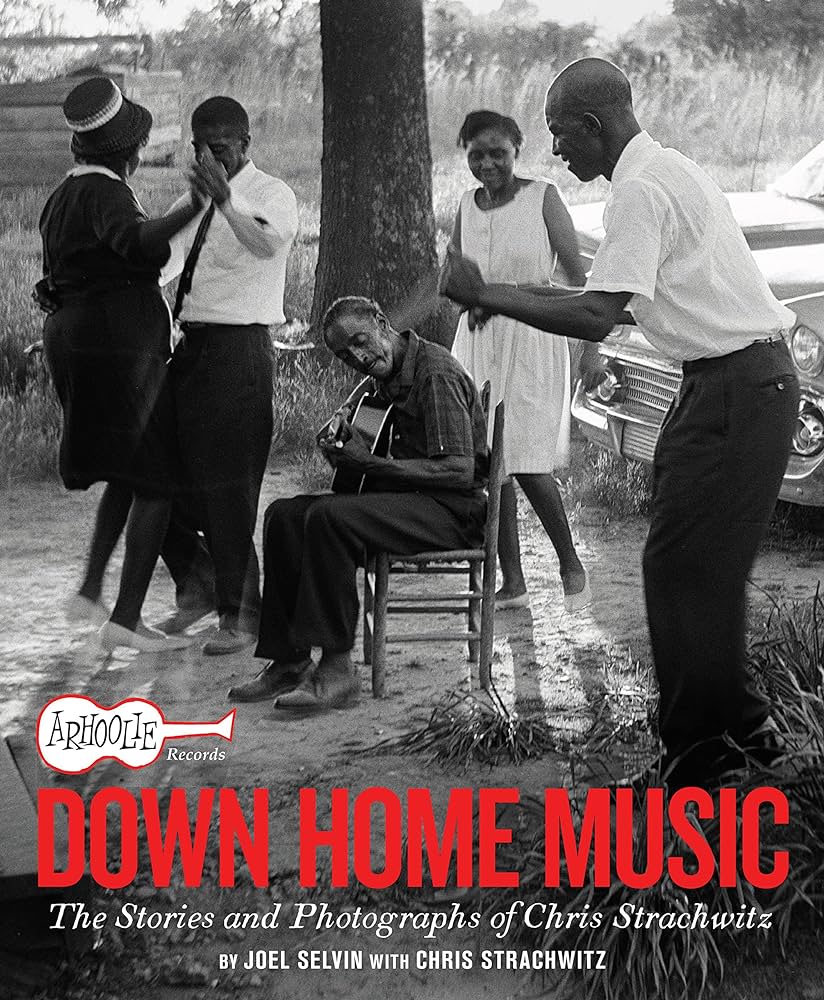

10. Arhoolie Records: Down Home Music: The Stories and Photographs of Chris Strachwitz, by Joel Selvin with Chris Strachwitz (Chronicle). Dying shortly before this book came out, Chris Strachwitz was a major figure in the documentation of American (and occasionally non-American) roots music as the head of Arhoolie Records. He recorded many blues, zydeco, Tex-Mex, folk, and old-time country discs, often going to where the musicians worked (usually in the South) and sometimes making what were essentially field recordings in humble low-budget settings. He took many pictures along the way, and this 240-page coffee table book has lots of them, spanning the 1950s to the 1990s. There are plenty of major figures, too many to list in a sentence or two, though some of them include Sonny Boy Williamson, John Lee Hooker, Rose Maddox, John Fahey, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Barbara Dane, Fats Domino, B.B. King, Lydia Mendoza, and Clifton Chenier. Some well known stars who were playing with or observing roots musicians are here too, like Carlos Santana, Bonnie Raitt, John Fogerty, and Ry Cooder. However, there are just as many images of performers who are barely known or even unknown, and while almost half a century is represented, the bulk of the pictures date from Arhoolie’s prime in the 1960s and early 1970s. While photo-centric books don’t figure as strongly as standard text-oriented ones on my lists, this is the best music photo book of the year.

Although Strachwitz didn’t boast much of his skills with a camera, most of the pictures are fine and sometimes striking from sheer visual points of view, aside from preserving important musical history. Maybe professionals with the techniques sometimes judged to be superior to semi-pros like Strachwitz would have taken photos considered of greater aesthetic quality. But it’s doubtful they would have gained the intimate trust that allowed him to take these pictures—in settings in which outsiders were sometimes viewed with suspicion—in the first place. There are so many exceptional photos that these again can’t be thoroughly listed in a mere review, but the one of Sonny Boy Williamson playing in an alley behind an Arkansas radio station in 1965 is particularly iconic. The trio he’s heading, with promotional handlettering for their radio show on the drum, almost seem to make a definitive pose for the birth of rock and roll, even if this was taken in 1965, long after rock’s actual birth. Not all of the most memorable images are of famous artists or from the 1960s, a 1986 shot of a blind harp musician and his wife working as street musicians in Guadalajara serving as another example.

The introductory 40-page essay by Joel Selvin gives a thorough history of Strachwitz’s work with Arhoolie Records, also noting his other accomplishments as the owner of the Bay Area record store Down Home Music and compiler of reissues of rare roots music. Strachwitz himself gives succinct yet detailed captions for all of the photos, relaying interesting memories of how the pictures were taken and what interested him in the performers. Often he had to put himself in precarious and sometimes even threatening situations to hear, photograph, record, and get to know the musicians, and such stories dot his memories. In his travels, particularly in the earlier years, he also got to experience a side of the United States—in ethnic communities with little representation in mainstream media, and often quite poor ones—that was experienced by few outside of those areas, as is vividly conveyed in some of the images. A “Rock and Roll Cafe,” as it was billed, in Texas in 1969 was a tin shack that looks on the verge of falling over with a good kick or two. Writes Strachwitz: “I didn’t stay for lunch, even though the door was open.”

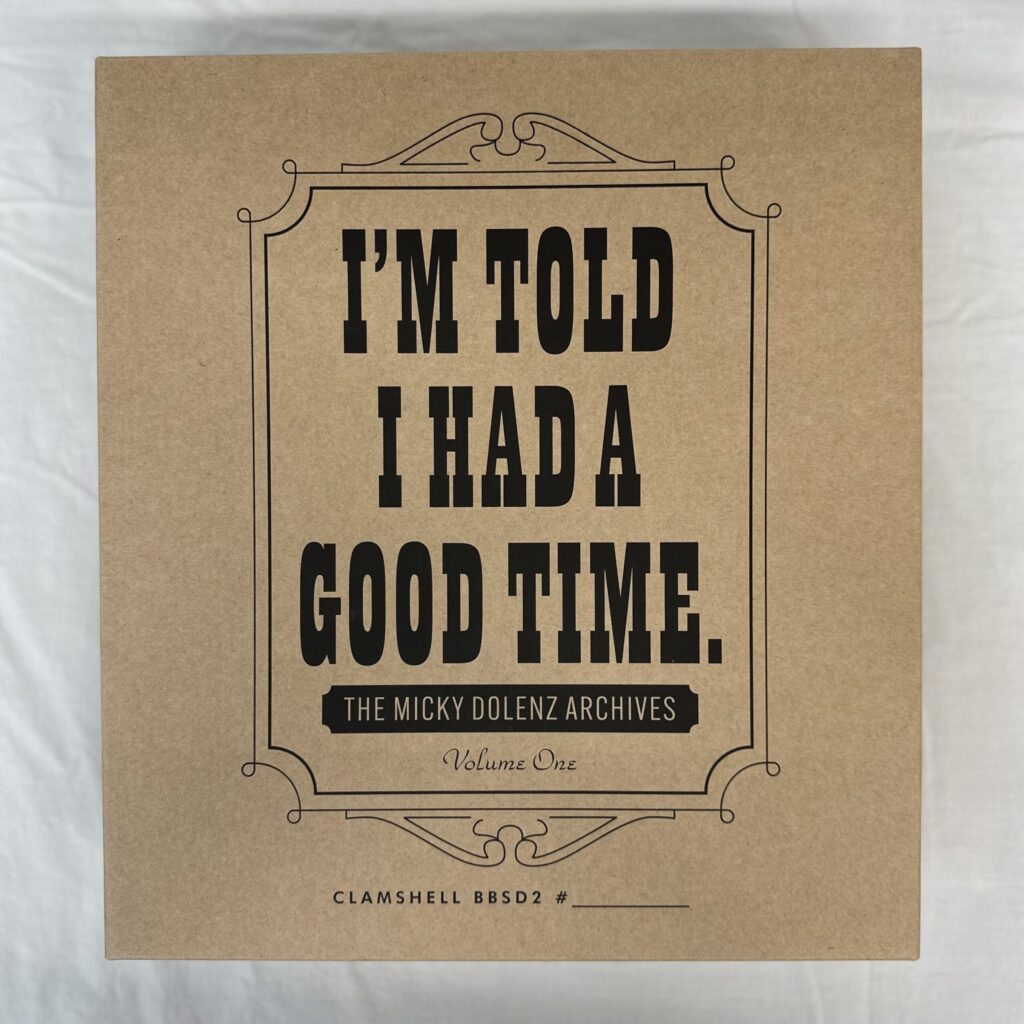

11. I’m Told I Had a Good Time: The Micky Dolenz Archives, Vol. 1 (Beatland). Micky Dolenz took and kept a lot of pictures while, and shortly before and after, he was in the Monkees, as well as accumulating memorabilia along the way. This nearly 500-page coffee table-sized volume reproduces a lot of the material, as well as presenting memories from Micky about the images in captions ranging from extensive to brief. While naturally the core audience for this is Monkee fandom, these aren’t just pictures of Micky and the group, as there are also figures with whom he toured and interacted. Of special interest are a few of Jimi Hendrix during the short time in summer 1967 when he was a support act on a Monkees tour, though there are also very good ones of Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Fats Domino from the Monkees TV special on which they appeared. Going back to his childhood and little known pre-Monkees mid-‘60s bands, the coverage extends to 1977 and his work as part of a duo with Davy Jones during that time, though the post-Monkees section isn’t large and the mid-‘60s take up the bulk of the book. Along the way are other non-Monkees pictures of note, including some of stars like Harry Nilsson, Cass Elliot, Eric Clapton, and Stephen Stills.

The text, based around interviews with Dolenz by editor Andrew Sandoval, is straightforward and witty, though not too lengthy on some of the Monkees-era photos, with quite a few of the images of the group on tour simply presented as they are. Encompassing early report cards to a receipt from the Beatles’ Apple fashion boutique and much else, one of the more interesting pieces of memorabilia is a memo from Screen Gems-Columbia Music recommending Dolenz’s composition “Randy Scouse Git”’s title be changed (as it was in the UK to avoid controversy, with the newly titled “Alternate Title” reaching #2). The post-1970 section is more interesting than some might anticipate, particularly Micky’s story of being cut from a program for the inaugural ceremonies of Richard Nixon’s second (and uncompleted) term. Dolenz speculates a Watergate joke he might have been overheard making could have responsible.

Among the more memorable observations in the captions is Dolenz’s remark about a picture of Hendrix aboard a Florida boat in July 1967: “It kills me. Jimi, you’re wearing a fur coat! It’s 90 degrees!” And there’s a frank reflection on his post-Monkees singles for MGM: “Looking back, I should have just continued doing Micky-the-Monkee-flavored stuff.” Some more extensive captions for some of the Monkees-era pictures would have been welcome, but for a massive Monkees history, there’s Andrew Sandoval’s The Monkees—The Day-By-Day Story, which like this book has exceptional production values.

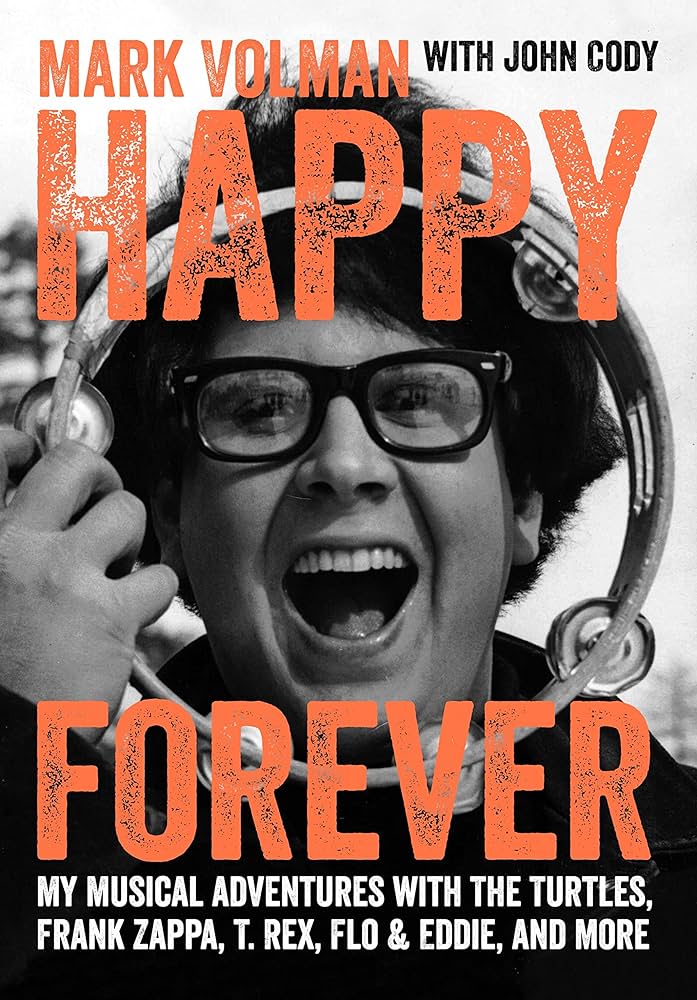

12. Happy Forever, by Mark Volman with John Cody (Jawbone Press). Along with Howard Kaylan, fellow singer Volman was the mainstay of the Turtles and Flo & Eddie. They were also part of Frank Zappa’s group in the early 1970s and sang backup for a bunch of records by other artists (notably T. Rex’s “Bang a Gong”), as well as doing some radio and other entertainment ventures. This has an unusual structure for an autobiography, as it’s more an oral history of Volman’s projects dominated by quotes from many professional and personal associates. Volman himself adds only occasional text, and it’s almost like a history of Volman as seen through those who knew and worked with him. It doesn’t suffer for that, but most of the perspective is on the outside, and it serves as much as a history of the Turtles and Flo & Eddie as it does a Volman memoir.

Plenty of people were interviewed for the book, most notably almost all of the other Turtles (including Kaylan, naturally); other members of the Mothers of Invention when Volman and Kaylan were part of the band; ex-wives and relatives; and lots of other musicians who interacted with Volman, sometimes extensively and sometimes slightly, from Alice Cooper and Ray Manzarek to Chris Hillman and Richie Furay. Of most interest are the detailed comments from fellow Turtles, including some who aren’t heard from much, like Jim Pons (who was also in the Mothers), Jim Tucker, Johnny Barbata, John Seiter, and Al Nichol. There are some conflicting and at times contentious accounts that, as in most acts with a happy-go-lucky image, reveal tension and infighting behind the scenes, as well as considerable business problems. There are also stories of how their hits were selected and constructed, and how Volman and Kaylan made the transition to a more underground comic duo after the Turtles broke up at the beginning of the 1970s.

Some of the comments, particularly from fellow legacy acts who didn’t actually intersect much with the Turtles’ paths, are more about the general 1960s/1970s rock scene (and particularly the unjust contracts and financial rewards) than Mark Volman. In keeping with the cliché reviewers often have to note, it gets much less interesting after the Turtles, Zappa, and Flo & Eddie. Sections about Volman’s entry into teaching for much of his career and his late-life embrace of Christian religious faith could have been shortened, indeed drastically reduced. So could repetitious testaments to his good nature and fine character, though there’s occasional criticism of his behavior.

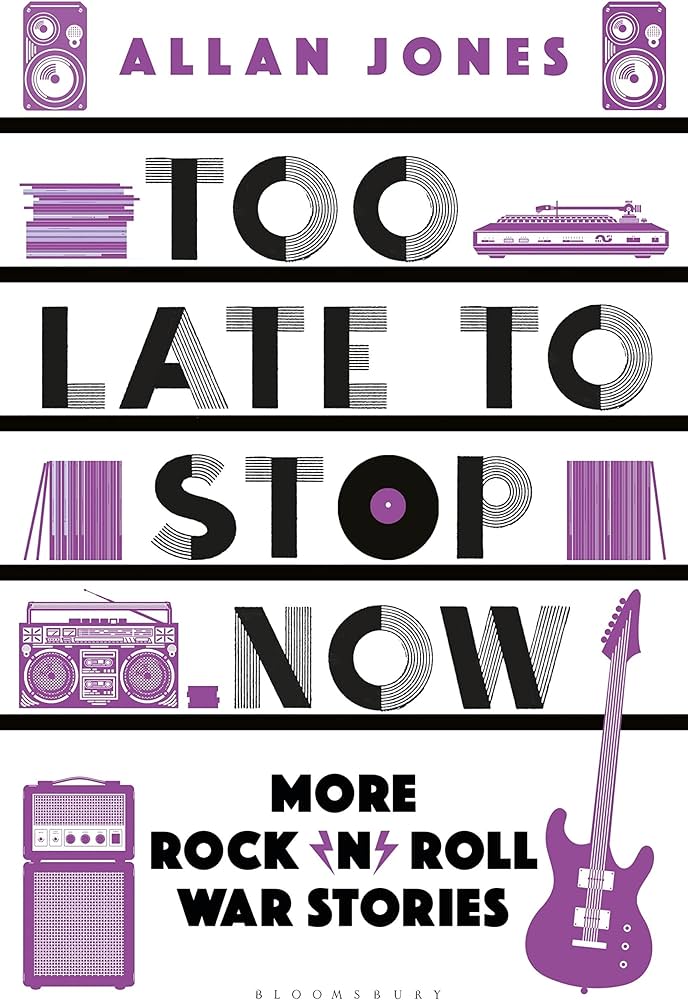

13. Too Late to Stop Now: More Rock’n’Roll War Stories, by Allan Jones (Bloomsbury). For more than twenty years from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s, Jones was a writer for and then editor of Melody Maker. Then he went on to a long stint at Uncut, where he had a regular column recalling his interactions, often though not always wild, with many musicians. These provided the basis for both a previous book, Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down, and this similarly structured follow-up. Several dozen chapters, usually very short ones, recap his interviews (and sometimes travels) with a host of stars and more cultish critical favorites, from Elton John and Peter Gabriel to Chrissie Hynde, Elvis Costello, and the Blasters. These usually emphasize the bawdy times and behavior at least as much as discussing the artists’ music, quite often ending up (or even beginning with) an onslaught of drinks quaffed by both Jones and his subjects. Such is the flow of alcohol that you wonder whether holding your liquor, or at least doing “when in Rome” amounts of booze (and sometimes coke), was considered one of the prime qualifications for and perks of the job.

Like Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down, this is largely pretty entertaining, if a little wearing when these mini-portraits give so much weight to substance intake and eccentric, at times aggravating behavior, often relayed with matter-of-fact amusement. Particularly in the later pieces, Jones sometimes goes in greater depth with more focus on the music than he did in his younger days. These are the most valuable chapters, all drawing from extensive first-hand interviews. The best are the ones spotlighting Hynde, John Cale, the Clash, and Wilko Johnson, where some historical perspective takes the place of more youthful searches for kicks. Although pretty long at 360 pages, it goes by faster than you’d think, as the wealth of chapters ensures a fair amount of white space at the beginnings and ends.

14. CSN&Y: Love The One You’re With, by Henry Diltz (Genesis Publications). At a price of about $375, this limited edition (1650 copies) book is of course not for the standard consumer, or even for the budget of the standard CSNY fan. Like other Genesis publications, however, it has considerable value for those who can afford it, or at least who are able to read if not own a copy, as I was. It has 835 photos by Henry Diltz—one of the most renowned rock photographers, especially for his pictures from the late 1960s and 1970s—and almost 60,000 words of text from Diltz, CSNY, and more than a dozen others who knew and observed the group. While the text doesn’t have much basic information that’s not in the numerous other books about the group and their members (and some of it’s taken from previously published sources), it’s entertaining and has some stories and observations that aren’t common fare, like John Sebastian suggesting either Graham Nash or Phil Everly when they were looking for a high harmony singer, and Stephen Stills having a different account than David Crosby and Nash as to how the three got together (the usual story being Cass Elliott was responsible).

While some of these pictures will be familiar to CSNY followers, plenty probably won’t, including some outtakes from the famous session for the first CSN (no Y at that point) album. And while the story of how the cover shot was taken and the house had been demolished by the time they went to try a reshoot is fairly well known to devotees, it’s interesting to hear the detailed accounts behind the photo session. Less interesting are the pictures and text about their several reunion tours, although those make up a low percentage of this volume. It’s not a thorough history of the band, as it’s built around the times Diltz photographed them; nor does it go into much depth as to their numerous side and solo projects, although some are covered for each of the four. Note that while numerous pages are reproduced from Diltz’s notebooks of the time, these are less valuable than you might hope. His observations are rather mundane, and more troublingly, his handwriting is simply hard to read.

15. 1964: Eyes of the Storm, by Paul McCartney (Liveright). From late 1963 through late 1964 (though mostly from late 1963 through early 1964), Paul McCartney took a lot of photos of the other Beatles, himself, associates, and the press, fans, and public that were chasing and sometimes hounding them around almost nonstop. This book has 275 of them, largely spanning their rise to Beatlemania in the UK in late 1963; their trip to Paris in early 1964; and their subsequent initial trip to the US in February 1964, though there are a few from late in that year. McCartney wasn’t a professional photographer—he never has made that part of his profession, actually—and the pictures are primarily of documentary value, though he was paying some attention to learning about composition and lighting from some of the photographers that regularly worked with the group.

Of course, this was a very historic time at which Paul was at the center, so even average pictures carry a good deal of significance. There are images of the Beatles backstage, onstage, in hotels, and on vacation in Miami, and of key figures close to them like Cynthia Lennon, Jane Asher, Brian Epstein, and road managers Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans. There are some unexpected musicians of note like French star Johnny Hallyday and drummer Mickey Jones. And there are plenty of pictures of fans, photographers, reporters, police officers, and anonymous observers to the giddy madness. There are also pictures taken by professional photographers from the time, particularly the ones in which Paul and/or the whole group can be seen. Some of the ones McCartney took are above average as standalone images, like one of George Harrison wearing two goofy hats on top of each other, and onstage shots of Billy J. Kramer and Sylvie Vartan.

With the abundance of books, many of them photo-oriented, covering the Beatles, some might consider this an inessential extravagance. But while it’s not part of the core Beatles library, it’s better than many such coffee table rock photo volumes. There’s not much text, but McCartney did write a thoughtful lengthy opening introduction that’s not just the too-common “I’m so honored to be able to present this book” paragraph or two many celebrities offer. He also has shorter, but still substantial, introductions to each of the five sections. There’s also a lengthy essay by Jill Lepore about the cultural context of the Beatles during this period and a similarly lengthy, serious appraisal of the artistic qualities of the pictures by Rosie Broadley, Senior Curator of the 20th Century Collections at London’s National Portrait Gallery, which had an exhibition of many of these photos around the time this book was published. McCartney’s captions for the photos are very brief, and it would have been good to have more in-depth comments and recollections, but on the whole this is more worthwhile than many such projects.

16. The Searchers: Crazy Dreams! Every Song from Every Session, 1963-2023 (peterchecksfield.com). A thorough critical Searchers discography might have a small niche audience, but I’m glad Peter Checksfield’s doing this and other such specialized books. This has entries for all of the songs they released, along with descriptive paragraphs that can be generous in their judgments. But they’re useful, especially since not too many people are familiar with this British Invasion band’s work aside from their handful of hit singles. Besides covering their singles and LPs, there are entries for work that might not even be known by serious fans, like EP-only tracks, non-LP B-sides, and foreign language versions. There are even thorough details about the fairly numerous recordings Tony Jackson did after leaving in the mid-1960s (even including an unreleased BBC session) and the few drummer/singer Chris Curtis recorded after leaving. The 1963 live Hamburg performances and their 1963 album-length demo of sorts taped at Liverpool’s Iron Door club are included, and their numerous BBC and TV performances listed.

Some info here and there is so obscure it might even be unknown to owners of multi-disc Searchers compilations, like the original performers of lesser known songs they covered like “Alright” (the Grandisons) and “Each Time” (the Bon Bons). It’s also spotted that there are two versions of “I’ll Be Doggone,” the more common one with a Frank Allen lead vocal, the less heard one with Curtis on lead from on a US LP. And did you know that the French version of “It’s All Been a Dream” has Mike Pender on lead vocals, though Tony Jackson sang the English-language original? It’s true the music, and hence unavoidably the text, gets less interesting after 1966, and the post-Sire comeback entries really play out the string. Reproductions of many record covers, many of them rare and foreign editions, dot the layout.

17. The Byrds: Every Album, Every Song, by Andy McArthur (Sonicbond). Although this won’t have much information serious Byrds fans don’t know, especially if you have Johnny Rogan’s mammoth books about the group, it’s a good and succinct overview of their recordings. Every single track on their albums is detailed and critically evaluated, including non-LP B-sides, bonus tracks on their reissues, the pre-first-album recordings that have been on the various packages with Preflyte in the title, and other bits that only show up on compilations. Some interesting trivia is sprinkled throughout, and the author doesn’t hesitate to criticize subpar songs or give slack to their post-1968 work, which was considerably inferior to their consistently innovative prior efforts.

18. Jerry Lee Lewis: Breathless! Every Song from Every Session, 1952-2022, by Peter Checksfield(peterchecksfield.com). Relentless researcher Checksfield continues his series of self-published reference books with a hefty volume detailing every song Lewis recorded. Presented in alphabetical order by song title, 707 separate titles are described in paragraph-long entries varying from a couple sentences to quite a few sentences. There are more than 707 entries, as Lewis recorded multiple versions of quite a few songs, and each separate version, including remakes, live performances, and the odd LP- or 45-only variation are also discussed. There are even tracks from bootlegs, of which there are more than many fans are aware of, and download-only items. You know it’s comprehensive when the entry for the 1966 recordings of the non-hit single “Memphis Beat” notes the substantial differences between the LP and 45 versions, and on the next page, it’s noted that a rare Japanese quadrophonic release has a slightly longer edit of a 1973 remake of the same tune.

You have to be a rabid fan to tackle such a mammoth catalog, and some of the assessments might strike some as too generous. That’s especially so when dealing with the many recordings Lewis made after the early 1970s, a time when he’s generally considered to have passed the point at which his releases were of much commercial significance or peak artistry. But Checksfield doesn’t hold back from criticizing, sometimes severely, efforts he deems subpar or flawed – not just from Lewis’s final half century, but going back to the Sun Records days. The writing’s clear and informative, and though the design is basic, it’s broken up by numerous black-and-white reproductions of record covers, inner disc labels, and screen shots of filmed performances.

19. Blood in the Tracks, by Paul Metsa and Rick Shefchik (University of Minnesota Press). It’s pretty well known – well, at least to a lot of serious Bob Dylan fans — that half of Blood on the Tracks was recorded in New York, and half in Minneapolis. Dylan actually recorded all the songs in New York, but decided to re-record some of them in Minnesota in the final week of 1974. The stories of the musicians who played on the records aren’t so well known, and this book discusses their backgrounds and post-Blood activities in depth, though the actual two Minneapolis sessions (December 27 and December 30, 1974) for the album are the heart of the narrative.

Although one of the session men, mandolinist Peter Ostroushko, did go on to became a pretty well known folk musician, the others didn’t. Their tales are of more interest than expected, especially as they’re sometimes dismissed as pretty anonymous figures that were assembled on the spur of the moment. It’s true Dylan’s brother, David Zimmerman, got the backup together very quickly, but several had done or been on records, with connections ranging from Leo Kottke and Olivia Newton-John to a fake Zombies. Although he (unlike the musicians and some others with ties to the sessions) wasn’t interviewed for the book, David Zimmerman had been involved in record production and music management, and it’s interesting to hear details of some of those, as not much has been written about him even in some huge Bob Dylan biographies. The sessions themselves are described in engaging almost play-by-play fashion. The impression’s also given that while Dylan was frustratingly uncommunicative to the musicians he used in New York, he was relatively friendly and open to suggestions in the studio where the Minneapolis sessions took place, Sound 80.

Some critics, fans, and musicians have contended that the more sparsely arranged New York sessions (whether in the takes chosen for release and the outtakes) were better and more in line with the emotions of the songs. Space is made here for those views, but also for ones by the musicians that the Minnesota performances were better, though one of the less aesthetic arguments is that they were more suited to being played on the radio. Some of the later section given to post-Blood on the Tracks work by the session guys, and their reunions in sorts of tributes to the album and Dylan, isn’t too captivating and could have been cut down. Even there, though, you get a good story about Peter Noone’s brief new wave group the Tremblers (in which one played), revealing Noone’s guitar skills were so lacking that his instrument was surreptitiously disconnected onstage, though “he never caught on.”

There’s just one mistake here that cries to be called out. There’s a reference to that Tremblers/Dylan sideman, Gregg Inhofer, being snubbed by Dylan when Bob was checking out the Stray Cats as a possible opening act at a Minneapolis club a few months after Blood on the Tracks was released. That would have been in 1975, but the Stray Cats didn’t form until 1979.

20. Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin): A Memoir, by Sly Stone with Ben Greenman (AUWA). Since Sly Stone hasn’t been heard from much in decades, and hasn’t appeared to be in the best shape when he has, it’s a surprise that he produced a memoir at all around the time of his eightieth birthday. Stone’s very colorful music and life have never been covered by a satisfactory biography, and while this account has its value, it leaves the impression there’s much more that could have been said. It’s not as lively as might be expected, telling the basic story of his amazing rise from producer/DJ/sporadic recording artist to superstar in the late 1960s and early 1970s. That’s about the first half of the book; the second half details his rather spectacular fall into both professional and personal abysses, and like many such memoirs loses considerable momentum as his life hits the doldrums.

The book is best, and Sly seems most engaged, when talking about his music. There are interesting details of songs, recordings, and albums, though it’s a bit like reading box set liner notes with a lot of participation from the artist. Be cautioned, too, that he spends almost as much time on his post-prime (say post-1973) records as his glory years, though almost anyone would feel those later discs are considerably inferior and less deserving of insights. There’s more that could be said about his time as a producer of acts like the Beau Brummels and the Great Society (with Grace Slick on vocals) at Autumn Records, though he does give more time than anticipated to his Stone Flower label for other artists in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

His numerous controversies—showing up late for shows (which he feels has been overblown, blaming this in part on getting multiple bookings, though few other artists of his stature from the era have cited this as a problem), heavy drug use, financial ruin—are relayed with some nonchalance, and without much regret or remorse for any pain it might have inflicted. The birth of his child with the Family Stone’s Cynthia Robinson suddenly crops up in the narrative with an aside that the pair had off-on flings while she was in the group; the departures of original Family Stone members are sometimes noted with brevity and little explanation; even an attack by one of his dogs on one of his kids that resulted in the child losing part of an ear is dispatched relatively quickly. It leaves a feeling of a guy who lacks almost as much of a full explanation for his fall from grace as dedicated fans do.

21. The Jive 95, by Hank Rosenfeld (Backbeat). With a bit of linking text, this is an oral history of San Francisco radio station KSAN, one of the most celebrated of the underground-oriented stations (for both music and public affairs) operating from the late 1960s to the late 1970s. Plenty of books are uneven, and among those, this is more uneven than most. There are a good share of interesting stories from DJs, engineers, local rock critics, and others who worked at or were associated with the station, as well as its predecessor KMPX, from which much of the staff moved to KSAN after a 1968 strike.

Some of those quoted (some from archival rather than first-hand interviews) are pretty well known, like original Rolling Stone music editor and occasional DJ Ben Fong-Torres; San Francisco Chronicle rock critic and author Joel Selvin; news reporter Scoop Nisker; and Raechel Donahue, DJ and wife of the station’s most famed figure, longtime DJ Tom Donahue. Some of the more colorful passages include accounts of how the Symbionese Liberation Army sent tapes to the station to broadcast their messages; a Tom Donahue interview of John Lennon around the time of Lennon’s Walls and Bridges album; and the general looseness of a time when DJs could play what they wanted, sometimes when they were stoned, and the general station operations were more casual and spontaneous than commercial stations would be in later decades.

It’s not a smooth read, however, as some of the comments are brief general observations about the San Francisco scene that have been written about for many years. Some of the transcriptions of on-air passages would probably sound a lot funnier when heard than read (and links are provided to hear some airchecks). Some quotes, especially toward the beginning, are uninformative in their brevity, and it’s not always easy to follow how the station’s programming and personnel evolved and changed. The mixed response to the introduction of punk and new wave into some programming by the late 1970s is covered, as is KSAN’s sad transformation into a mainstream popular music station, and then a country station, with none of its former identity intact. There’s some imperfect editing and a few factual mistakes that should have been caught, like identifying Jefferson Airplane’s first woman singer, Signe Anderson, as “Signe Wilkerson.”

22. Rod Stewart: The Classic Years, by Sean Egan (Backbeat). While this is more of a critical overview than a biography, and covers a somewhat wider era than what many would consider Stewart’s core classic years, it’s still a worthwhile endeavor. The focus is roughly on the years 1969-1972, when Stewart made what almost everyone considers to be his best solo albums (particularly Every Picture Tells a Story), and also had a simultaneous successful career as lead singer of the Faces. Egan draws on some first-hand interviews with insiders, especially Kenney Jones and Ian McLagan of the Faces; drummer Mickey Waller; manager Billy Gaff; and Rod’s romantic partner of the early 1970s, Dee Harrington. There are detailed critiques of the albums that, unusually for books of this sort, don’t hold back in pointing out their shortcomings, even for records the author obviously admires. Egan, like most critics, doesn’t like Stewart’s post-1972 records as much, but there’s still a lot of coverage of them up through the early 1980s, although it’s not as extensive as what’s given the previous ones. It can be tough going to go through the tracks of records that are both more boring and not as familiar as the classic stuff, and the best of the book — like the best of Stewart’s discography —lies in the earlier material, particularly what’s dealt with in the first half of this volume.

23. Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir, by Lucinda Williams (Crown). Williams has had a life more interesting than that of the usual musician who rose from cult to mainstream popularity. She didn’t have records that charted until she was well into her forties. As she overlapped the country, folk, and rock worlds, the record industry did not quickly embrace an artist they found difficult to classify. Although a little on the brief side, her memoir is a good read, beginning with a troubled upbringing with a mother struggling with mental illness and failure to complete high school owing to clashes with authority. She needed to constantly move with her family growing up, and continued to move from New Orleans to Austin to Los Angeles to New York to Nashville as she tried to forge a living in the music business, making her debut album for Folkways in the late 1970s for a $300 fee. There were numerous troubled relationships on the way, some of which informed her songwriting, though a lot of the text does discuss her music and records as well as her personal life.

Some of the most interesting sections describe clashes with record labels and producers in her long journey toward establishing herself as an acclaimed recording artist. She deliberately got herself booted off RCA by criticizing the label in public; her contract was bought from Rick Rubin when an album was going to be delayed by two whole years due to a business complication unrelated to her record; producers mixed some of her work to her dissatisfaction, leading to some re-recording and a permanent falling out with a colleague. By the 21st century she’d achieved considerable sales and widespread critical praise, yet there’s little in the book from the last fifteen years. Indeed the depth of coverage trails off considerably by the time it reaches the 2000s, which might disappoint some fans, though the previous years are documented in reasonable depth.

24. Cream: Clapton Bruce & Baker Sitting on Top of the World (Schiffer Publishing). This slim picture-oriented book is pretty narrowly focused and thus might have a narrow appeal, even considering Eric Clapton and Cream remain hugely famous. It’s devoted to the group’s San Francisco shows at the Fillmore and Winterland between February 29 and March 10 in 1968, during which some official and unofficial recordings were made. The numerous pictures vary from highly professional to dark, blurry amateur audience shots; there’s a big difference between the ones by the top rock photographer of the time, Jim Marshall, and many of the others. These are broken up by text commentary and memories from some who were there, including filmmaker Tony Palmer and engineer Bill Halverson. Some of the writing could have benefited from some editing and higher professionalism, but there’s some interesting information for devotees, particularly those clarifying what was played when and what circulates on unofficial tapes. Memorabilia like tape boxes, posters, and ads are also included.

25. The Tremeloes: Even the Bad Times Are Good!, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). Peter Checksfield’s books are for the serious fan/collector. But even compared to most of his other volumes—including two others that came out in 2023 and are reviewed above, on Jerry Lee Lewis and the Searchers—this has a pretty specialized audience. It’s similar in format to those books, going through all of the Tremeloes’ releases (including those when they were Brian Poole and the Tremeloes from 1962-66) chronologically, with descriptive entries for each. These are enhanced by first-hand and archive quotes from the members (including Poole), as well as quite a few photos and reproductions of record sleeves. The members’ solo releases—not just Poole’s, but the yet lesser known ones of other guys in the group—and tracks that found release on archival comps are included, and many covers of Tremeloes’ material noted. Appendices include a timeline, discography, and thorough list of TV and film appearances, and BBC radio sessions.

All of this is assembled and written well, and the book would rank higher had I been more interested in the Tremeloes. I do have most of their 1960s recordings, including the ones with Poole as a lead singer, which are barely known in the US. But aside from their two big US hits (“Here Comes My Baby” and “Silence Is Golden,” both in 1967), I don’t rate them too highly or find them to have much of a musical personality. Certainly Checksfield rates them pretty highly, praising much of their output enthusiastically, though there might not be many other fans (let alone critics) who find their versions of Joe Tex’s “Show Me,” Bob Dylan/The Band’s “I Shall Be Released,” and Brenda Holloway’s “Every Little Bit Hurts” superior to the originals.

If like me you’re not a big Tremeloes fan but are a big fan of ‘60s British rock in general, however, this is more interesting than you might expect. There were a lot more covers of Tremeloes material than most people would guess, some from pretty unlikely sources and non-English-speaking countries, and it’s unlikely they’ve ever been or will be traced with as much detail as they are here. Some of the stories behind how they changed personnel, found their songs (and passed on “Yellow River” before Christie had a big with it), or made sporadic attempts to change with the times are reasonably engaging too. Despite their limited US success, they had quite a few hits that charted strongly in territories ranging from the European continent to New Zealand and Zimbabwe, as well as many in their native UK. It’s quite a struggle, however, to get through the final sections on their post-1970s comebacks, reunions, and numerous re-recordings of material from their prime.

26. Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, by John Szwed (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Harry Smith’s life was so complicated that it’s hard to classify him, although another subtitle reads “the filmmaker, folklorist, and mystic who transformed American art.” Only part of what he did, and hence what this biography covers, is related to music. But his musical activities, which are covered in detail, were notable. He recorded and assembled numerous albums, by far the most well known of these being the three-volume Anthology of American Music. That three-volume series of reissues of various folk discs of the 1920s and 1930s that influenced important performers of the folk revival, some of whom (like Jerry Garcia and Bob Dylan) went on to become rock stars. He also produced the first Fugs album. But as extensive as his musical ventures were, including collecting and taping plenty of recordings of far more arcane performers and styles, these didn’t even account for the majority of his work. That also entailed experimental film, painting, constructing/collecting string figures, and collecting and classifying/disseminating paper airplanes, Ukranian-decorated eggs, Native American dress, and other material.

The range of his work, and his generally itinerant existence, presents a challenge in documenting his life. The author does about as good a job as could be done, but there are many gaps and uncertainties that probably can’t ever be pinned down. The low ranking on this list doesn’t reflect the quality of the research or writing, which is presented in an accessible and readable fashion, though it sometimes roves pretty widely back and forth in chronology. It’s more an indication of my relative lesser interest in Smith’s non-musical doings, though his film, animated and otherwise, like his Anthology of American Music volumes, had an influence outweighing the relatively few people who saw or heard these when they were first produced.

His erratic personal habits, which saw him nearly destitute and unable to take care of essential needs like food, shelter, and health care for much of his adult life, are also described, and are often disturbing. Smith lost or, worse, willfully destroyed much of what he created and collected; often failed to finish ambitious projects, although he completed a good many as well; often freeloaded from friends and benefactors without compensating them; and frequently insulted those same friends and benefactors, as well as audiences, though he could be generous and kind to others as well. His treatment of Allen Ginsberg, who put him up and to a degree financed him toward the end of Smith’s life, was sometimes exploitative and cruel. Some might have rationalized he was worth putting up with because he was a genius folklorist of sorts, but he was a pretty unsocialized one, which makes the man more difficult to admire (and read about) than his accomplishments.

27. Fashioning the Beatles, by Deirdre Kelly (Sutherland House). I’m not nearly as interested in the Beatles’ clothes and haircuts as I am in their music. But it’s undeniable their fashion was visually interesting and enhanced their huge appeal, and this book is a reasonable overview of the many phases it passed through, from their Hamburg leather days through the matching Beatlemania suits, psychedelia, and more casual wear near the end of the 1960s. While the general outline of these changes is known to many Beatles fans, this does have some unusual info that isn’t well-trod, like the fur coat George Harrison wears in the January 1969 rooftop concert being the same one he wore to his wedding three years earlier. For that matter, during their 1969 Get Back sessions, Paul McCartney wore the same shoes he’d worn as part of his Sgt. Pepper uniform. The numerous shops and designers patronized are detailed, down to the Le Château store John Lennon and Yoko Ono bought some clothes from during their 1969 Montreal bed-in. Bet you didn’t know, either, that all of the Beatles except Harrison wore suits by Nutters of Savile Row on the famous photo on the cover of Abbey Road. Some color and black-and-white photos illustrate their constantly shifting image, and it’s interesting to see them modeling Lybro jeans in a 1963 ad that wasn’t printed at the time, as well as Ringo Starr modeling a Tommy Nutter suit in a 1969 Vogue magazine ad.

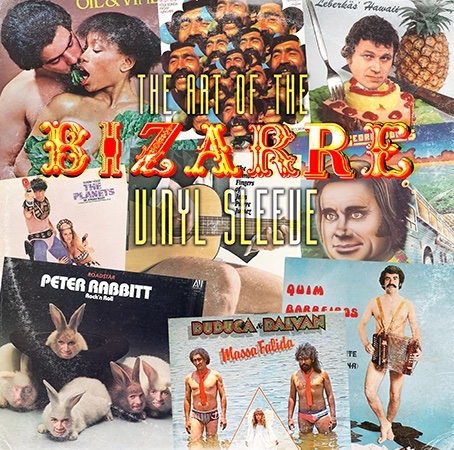

28. The Art of the Bizarre Vinyl Sleeve, by Simon Robinson and Steve Goldman (Easy on the Eyes). Co-author Steve Goldman has spent a lot of time collecting the strangest vinyl record sleeves he could find, which are often among the ugliest you’re likely to find. A lot of them supply the illustrations for this 180-page book, accompanied by quite a bit of text describing (and often gently mocking) the artwork, often filling in the background on these oft-obscure performers. Sure it’s a bit of a novelty volume for a niche among the record collecting crowd. But there are a fair number of collectors in that crowd who appreciate the weirdness of these designs, most from LPs, though some singles are included. That’s the case even if most wouldn’t want to actually buy or collect many of them (even at the cheap prices they often sell for if they can be found), let alone listen to them. And from the description of the music on the discs, many of them do seem like they’d sound horrible, especially as many were self-pressed vanity efforts, outings by minor celebrities, discs by semi-pro folk musicians, and the like.

There is, however, a pretty wide range of oddities selected from all over the world, including areas not usually covered by Western pop journalism, like the Eastern bloc. And for all the obscurity of many of the entries, questionable artwork on some releases by big-name artists are here, including sleeves on records by the Village People, Prince, and Deep Purple. The odd respectable cult favorite makes it too, like Lothar and the Hand People’s debut LP, adorned with yearbook-quality photos. Designs by respected labels are here, one surprise being a Box Tops best-of on Rhino, where the cover photo had one of the guys (not Alex Chilton) making a ridiculous ugly grimace. On occasion the artists or others involved in the process were tracked down and offered some details, although the stories behind the designs of many of these records—and the careers of many of the artists—remain and are likely to remain mysterious.

The following books came out in 2022, but I didn’t read them until 2023:

1. The McCartney Legacy Volume 1: 1969-73, by Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair (Dey Street). Running a little more than 700 pages, this would have certainly placed pretty high on my 2022 end-of-year list had I read it in time. It would have rated even higher than it does if I was more of a solo Paul McCartney fan, though the Beatles are my favorite group, and I think his contributions to that group were as good and important as John Lennon’s. But if you are a big McCartney fan, or even if you aren’t but are a big Beatles fan and/or at least interested enough in his early solo years to find out more about them, this probably won’t be beat. The original intention was to focus on his recording sessions, and those are described in great detail, along with some of his more informal demos, most of them still unreleased. This is woven together, however, with general in-depth coverage of his professional and personal life, including a lot about his wife Linda and the group he formed around him and her, Wings.

This should be hailed above all for finally laying down, with dates and details, the particulars of almost all of his studio recording sessions during these years, which encompassed his first five post-Beatles albums (whether with or without Wings), numerous non-LP singles, and other recording/songwriting projects. Those demos —often uncirculated even unofficially — are often bountifully described, too, including more than a couple dozen he recorded between McCartneyand Ram, among them a good number of songs he wouldn’t otherwise record. There’s also a lot about his disputes, and lawsuits, involving Allen Klein, and the protracted process that he initiated as necessary to dissolve the Beatles partnership. And there’s much about the various Wings lineups, illustrating how Paul, and to some degree Linda, had a hard time ceding as much creative control, commitment, and money as his sidemen would have liked.

However, the authors give Wings and McCartney more respect for what they accomplished than many music critics did and have – not just Band on the Run (whose Nigerian sessions in Lagos are among the more interesting sections), but everything else as well. Even “Bip Bop,” to pick on a song that’s probably been singled out for more harsh flak than anything else he did at the time, is examined with seriousness, as are pretty obscure B-sides like “I Lie Around” and “The Mess.” If Paul and Linda could be callous with their employees, the point’s also made that they could be generous too, and overall they don’t come off as worse than average in the rock star behavior department. The photos that dot the text are good and unusual, and the text is clear and, if more enthusiastic about his music of the period than I am, not blind to its flaws.

One minor but unfortunate flaw in the book is the lack of an index, and clearer designations as to what was released from his sessions at the time, what came out on archival reissues, and what’s never come out, though that can be deduced from the text. This is, by the way, volume one of a multi-part series, with another half century or so that could potentially be covered in the future. For me, those will hold much less interest past the years documented in this volume, which were the most interesting of his post-Beatles life from both musical and personal angles.

2. Decades: Donovan in the 1960s, by Jeff Fitzgerald (SonicBond). This is part of the very extensive, and rapidly growing, series of SonicBond books devoted to detailed track-by-track overviews of the work of specific recording artists, both famous and cult. Donovan’s one of the more famous ones, and this slim (134-page) survey wisely sticks to his 1960s output, although there’s a brief overview of his post-‘60s career. Every track he released in 1965-1969 is discussed, usually for at least a paragraph. It’s well-written and rich in detail, not just in how the track sounds, but some of its sources (particularly in the occasional instances when Donovan covered someone else’s song) and some little known stories and trivia associated with some of them. Although it’s primarily a critical assessment rather than a biography with first-hand research, Fitzgerald did interview arranger John Cameron, and several interesting comments for those tracks on which Cameron worked are here. Even for a Donovan fan like myself, some of Fitzgerald’s evaluations are on the overly generous side. On the other hand, the singer-songwriter’s been so generally underrated it’s good to see him given serious critical analysis that doesn’t get stuffy, with interpretations that some might find debatable, but aren’t overwrought. There are very occasional factual mistakes, but on the whole it’s accurate and useful for serious Donovan admirers.

3. Soul Survivor: The Autobiography, by P.P. Arnold (Nine Eight). Although she’s African-American, Arnold is much better known in the UK in the US, as she had some moderate British hit singles in the late 1960s. She also had more overlap with the rock world than most soul singers, as she recorded for Immediate Records and worked with Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham, the Small Faces, and the Nice. While her discography isn’t the work of a major artist, her memoir is an interesting journey through the highs and lows of the music business. In some ways, she had a lot of good fortune: getting asked to stay in the UK after touring there as an Ikette with Ike and Tina Turner, the Immediate and rock star connections leading to moderate chart success, and living the high life of just-post-Swinging London with plenty of celebrities. The lows were really low: getting raped by Ike Turner as an Ikette, losing her young daughter in a car accident, escaping an abusive marriage as a teenager when she became an Ikette in the mid-‘60s, and losing much of her lavish lifestyle as she fell out of favor with the music business and couldn’t get a recording deal.

Arnold also had relationships, though sometimes brief, with a number of rock legends, most notably Mick Jagger (begun when she toured with the Turners on a UK tour headlined by the Rolling Stones), Steve Marriott, Rod Stewart, and CSNY/Manassas bassist Fuzzy Samuel. These are detailed without sensationalism, as are her professional interactions with numerous major figures she crossed paths with along the way, like Barry Gibb, Nick Drake, Doris Troy, and Brian Jones. All of the aforementioned are recalled in very positive terms, but some others left much worse impressions, like Lulu, P.J. Proby, and John Mellencamp. She felt she was too rock for black audiences and too soul for white rock listeners, making it harder for her to find record deals or make the music she most wanted to. Arnold made some decisions she regrets in her attempts to continue her career in the UK, Los Angeles, and other places, especially in the effect all the moving had on her family and the stress of often living beyond her means. She doesn’t spare herself in attributing responsibility, and while the underside of the music business isn’t the main or sole focus, it’s evident how much of a toll it takes on those who make some inroads without quite becoming stars.

4. Living on a Thin Line, by Dave Davies with Philip Clark (Headline). Considering what a major and beloved figure he is, this autobiography by Kinks lead guitarist and occasional songwriter and lead singer didn’t get much attention. In part this might be because it’s actually his second memoir; the first, Kink: An Autobiography, came out back in 1996. It’s not a sequel covering the intervening years, in which he hasn’t released much music at any rate. It too covers his whole life and career, and while there have been more than 25 additional years in the meantime, the great bulk of it takes place earlier, and much of that is devoted to the Kinks’ first and greatest decade. Inevitably there’s a lot of overlap between the two books, though no actual text from the earlier volume is recycled. So even major Kinks fans might wonder if it’s worth reading if they already have Kink.