In early 1966, Bob Marley left the Wailers to live with his mother in the United States, although the Wailers had released a string of generally pretty popular (sometimes extremely popular) singles in Jamaica over the previous year and a half. His mother had moved to Delaware about three years previously, establishing US residency after marrying in American.

For eight months, he worked at a series of menial jobs in Wilmington. These, in keeping with the inexact details of Marley’s early years, have variously been reported as including stints as a janitor at the Dupont Hotel, a waiter, a dishwasher, a parking lot attendant, a lab assistant at DuPont chemical company, and driving a forklift at a Chrysler auto plant assembly line. He probably didn’t work at all of these jobs (or at least all of them during the same visit), apparently returning to the US on a few other occasions over the next few years to combine visiting his mother with laboring for dollars.

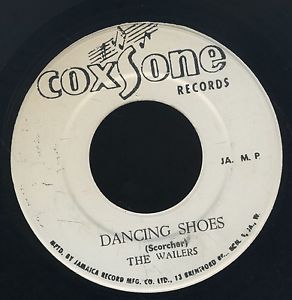

A 1966 single by the Wailers, recorded without Bob Marley, as Marley was in the midst of an eight-month stay with his mother in the US.

It says much about the state and size of the Jamaican industry that Marley could make more money finding menial work abroad than he could as one of ska’s hottest stars. It would have been inconceivable, for instance, to find Curtis Mayfield—the Wailers’ biggest influence—quitting the Impressions to work in an auto plant out of economic necessity just as they were tasting the heights of success. But despite their Jamaican hits, they weren’t making much money, subsisting for at least a while on wages of three pounds a week each that were doled out by their producer, Coxsone Dodd. Dodd let Marley sleep in the studio for a time, but even that was in consideration of Bob doing extra work rehearsing other artists on Dodd’s Studio One label.

Ian McCann, editor of the UK monthly magazine Record Collector and co-author of Bob Marley: The Complete Guide to His Music, wonders if the early Wailers were as successful as some accounts would have it, even though surviving charts indicate at least few of their mid-‘60s singles made the Jamaican Top Ten. “It’s worth bearing in mind that if the Wailers were so big, where were all the other producers trying to tempt them away from Studio One, as invariably happens in Jamaica?,” he asks. “If The Wailers were having a string of smashes, someone would have lured them away.”

One also wonders why Dodd didn’t try harder to get Marley to stay in Jamaica if the Wailers were selling so many records—perhaps by increasing his measly wages, for instance, or offering him at least something in the way of royalties. Maybe Dodd thought the Wailers would do well enough without Bob. And, though it’s not often emphasized in Marley biographies, the Wailers did make singles without Bob in 1966 that were very good, like “Dancing Shoes,” “Can’t You See,” and “Sinner Man,” apparently at least sometimes with significant Jamaican sales.

The biggest mystery of Marley’s 1966 Delaware sojourn, however, surrounds its termination. Some accounts have it that he simply tired of the menial work and (during at least in some months of his visit) cold weather, and wanted to get back to making music with the Wailers, using the $700 he had saved to help start the band’s own label. That seems logical enough, but it’s also sometimes been reported that a notice from the Selective Service sealed his determination to leave the US.

That makes for a dramatic story within the story, but there’s confusion about when or even if this happened. Marley was not a US citizen, but young non-US men who resided in the States for more than six months did risk getting drafted into military service. It’s unclear whether the notice was instructing him to register for the draft or actually drafting him. It’s also unclear whether this happened in 1966 or on a subsequent visit to his mother in Delaware in the late 1960s and early 1970s. One Marley biographer wrote that the Selective Service didn’t even have a record of Bob in its system—though given how disorganized the government sometimes was about such matters, that wouldn’t necessarily mean they never contacted him.

Whatever happened or didn’t with the Selective Service, he was back in Jamaica with his wife Rita in late 1966. Not long afterward—January 1968, according to most sources, though a January 1967 date has also been given—he came into contact with American soul singer Johnny Nash, which in turn led to a deal with Nash’s manager, Danny Sims. Sims would pay Bob, Rita (who was in essence taking Bunny Livingston’s place in the Wailers while Bunny served a jail term in 1967-68), and Peter Tosh $100 a week each to write songs. Livingston wasn’t part of the deal, as he was still in prison.

It’s not entirely clear what Sims and Nash hoped, or at least hoped most, to gain by the association. Probably they wanted to place some of their songs—especially Marley’s—with American artists, as the publishing royalties for US hits would mean a big payoff. They were also probably considering some of the material for Nash, who would indeed make one of Marley’s songs a big hit, though not for nearly five years. As a longer shot, there was the possibility of getting hits in North America and Europe for records performed by Marley and/or the Wailers themselves, though they were unknown in those territories, and reggae itself was barely known anywhere outside of Jamaica.

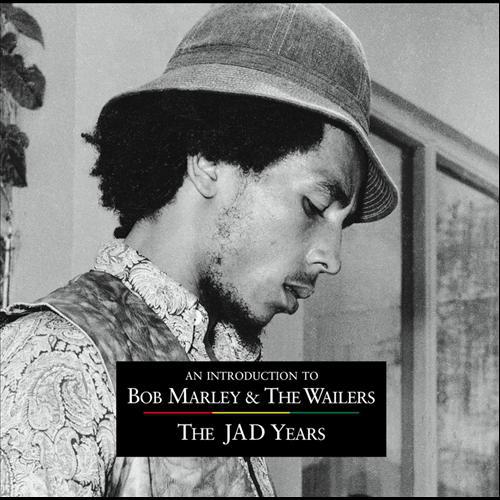

Probably starting around early 1968, Bob, Peter, and Rita began making demos for Sims and Nash’s JAD company. It’s not wholly certain whether these were intended to be shopped to other artists to generate possible covers; to get considered for interpretation on Nash’s own releases; to get a deal for the Wailers and/or Marley; or, if the demos were good enough, to even gain overseas release. Their purpose was probably some combination of all of these alternatives. The Wailers certainly had plenty of material to offer for consideration. Many tracks were cut for JAD—211, according to a 2004 Universal Music press release announcing a licensing deal between the two companies.

Here’s my first question about this situation for which I can’t figure out an answer:

If Johnny Nash was so hot on Marley as a songwriter, why didn’t he record any of Marley’s songs in the late 1960s?

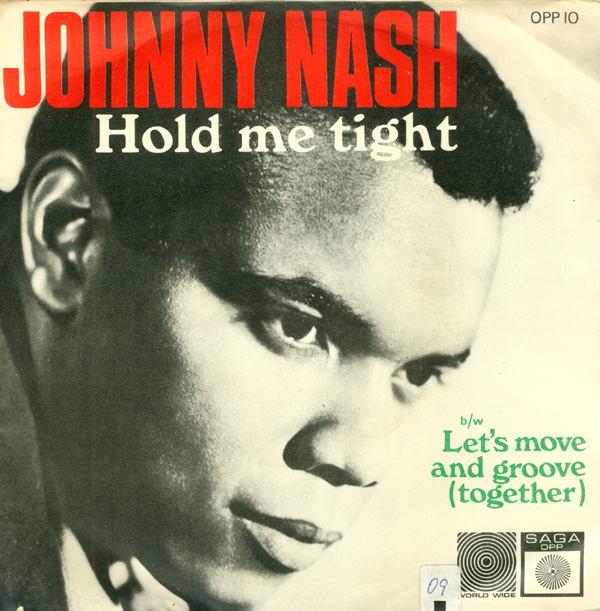

Nash, previously a journeyman soul singer without much in the way of either hit records or artistic distinction, made #5 in both the US and UK with a breakthrough hit that drew heavily (and quite skillfully) upon Jamaican rock steady music, “Hold Me Tight.” Bob’s material would have fit in well with his new direction. Why didn’t he put any Marley tunes on his records of the period? And why was the one Wailers song he did cover at the time a Peter Tosh composition (“Love,” on his Hold Me Tight album, marking the first high-profile cover of a Wailers song abroad), not a Marley tune?

Of course, Nash eventually would have great success with a Marley song when he took “Stir It Up” into the UK and US Top Twenty in 1972 and 1973 respectively. The album Johnny recorded around that time, I Can See Clearly Now, had some other Marley compositions. Why wait so long? Especially since “Stir It Up” had been around for a while, the Wailers recording the original version for a single back in 1967?

Here’s a more sensitive mystery:

If Bob Marley (and Rita) were being paid $100 a week each by JAD for writing songs, why did Bob periodically return to Wilmington to take more of the kind of menial work that he (according to Rita’s memoir) had sworn off for good after a vacuum cleaner exploded at one of his 1966 jobs?

$100 USD won’t even get you a good guitar today, of course, but back in the late 1960s, it went pretty far in Jamaica. A lot farther, at any rate, than the three weekly pounds that had been Bob’s wages from Coxsone Dodd for a while. Even considering that the Marleys had a growing family, it would seem the $100 stipend, along perhaps with some other money they picked up selling records and performing, would be enough to support themselves without Bob having to go back to work in a Delaware auto plant or some such thing.

Was the $100/week salary not in place for the entire period during which Bob was under Sims’s management (until around late 1972/early 1973)? Was it simply still not enough? Or did Bob just want to be able to periodically visit his mother, picking up some work while he was there to help things along?

Did Bob even want to use those trips as a chance to see whether the Wailers might want to join him in the US to try and make it in the States? A couple accounts (predictably giving different years) have it that Marley actually wrote Livingston asking him and Tosh to come to the US to resume the Wailers’ career in the States. Uninterested in relocating, Bunny didn’t reply.

Whatever the reasons for them taking place, the post-1966 trips Marley took to the US and the jobs he took there—and, according to several sources, there were more than one such trips—don’t add up to me. Why would he have needed the money that badly? And if he didn’t need the money that badly, why would he have spent any weeks or months at such mundane jobs, as it would have taken precious time away from the music that was his main priority? Even if Sims wasn’t paying him and/or Rita $100 per week anymore, wouldn’t Sims have wanted Marley to concentrate on music instead of manual labor, and wanted to have given him some incentive not to make other work his focus? Could his ties to the other Wailers have been looser than is usually assumed, and Bob looking for options that might have involved a career without them?

That leads into the third and final of this series of Marley mysteries posts. The Wailers finally got a big record deal after relocating to the UK, with some bumps on the road. But why did they end up there, and were they really as unknown in the UK as is usually assumed?