The EP, or extended play, record has been around in some form about as long as records have. In rock music, they’ve been issued in several formats over the years, from seven-inches and twelve-inches to ten-inches, CDs, and bonus seven-inches with full twelve-inch LPs. Back in the 1960s, they were usually four-song compilations of tracks that were also and/or previously available on singles and albums. They didn’t take off to a meaningful extent in the US (though that changed a bit in later decades), but were a popular medium in the UK and numerous other countries. In fact, for quite a few years they were the primary format in France, which issued more Beatles EPs than Beatles singles before 1967.

The most interesting EPs—certainly if you weren’t living in the countries of their origin—were those that presented material that had not been available on singles or LPs. These days, just about all of the songs that were exclusive to certain rock EPs are available on reissues. But it’s neat to look back at the ones that used the EP as a vehicle for fresh sounds, not as a marketing tool for recycling or repurposing songs that ultimately made more sense to buy on singles and albums, if you had the budget.

Here’s an opinionated summary of the most noteworthy ’60s EPs, most of them from British acts, and most of them UK releases. It was relatively rare for US artists to issue EPs that unveiled new material, but there are a few of those too. All of these are seven-inches. Some purists might question whether a few three-song seven-inches are more properly classified as “maxi-singles,’ as the term was sometimes given in the UK press, but I’ve put them on too. I haven’t tried to rank them in quality, instead listing them in the order in which they were released.

The Big Three, At the Cavern (Decca, November 1963). It’s a little strange to lead off this list with one of the least musically interesting items, but we’re going in chronological order. The Big Three were one of the most popular Liverpool groups, and occasional comments in oral histories from those who were there suggest they were on par with, or even better than, the Beatles live. That assertion certainly isn’t borne out from their small official discography, which is energetic but mundane Merseybeat fare. They could play forcefully and had some of the top instrumentalists on the Merseyside. But when you don’t write many songs, and what little original material you have is weak, you certainly can’t bear comparison to the Beatles even if you did blow them off the stage at the Cavern (which I doubt happened, but no matter).

The Big Three never released an album, but they did manage to put out four singles and an EP that was, as the title says, actually recorded at Liverpool’s most famous club. As the only disc by a Merseybeat band taped at the Cavern, it’s of notable historical interest for that alone. The audience noise and introduction by compere Bob Wooler (famed for his role in the early Beatles’ career as fan and general advisor) add to the atmosphere. Musically it’s a truer representation of their sound than their studio 45s, where they were given some inappropriately lightweight pop material. But let’s be real here — it’s competent but not great, in part because two of the tunes are overdone rock classics (“What’d I Say” and Chuck Berry’s “Reelin’ and Rockin'”), and the other a not-so-great version of “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah.” The one group original, “Don’t Start Running Away,” is just passable.

There could have been a much more famous recording made at the Cavern in 1963. As many Beatles fans know, George Martin was considering taping the Beatles’ first album there, but then figured they could re-create their live excitement in the studio. Which they did, magnificently, for their debut LP Please Please Me.

The tracks on the Big Three’s Live at the Cavern EP—fairly successful in the UK, by the way, where it reached #6 on the EP charts—haven’t been hard to find since 1982, when they were on the Cavern Stomp compilation, which gathered all thirteen of the cuts they released in the ’60s. It includes a cover of “Bring It On Home to Me” from the 1964 various-artists compilation At the Cavern, also recorded at the club, and also with an introduction by Bob Wooler.

The Rolling Stones, The Rolling Stones (Decca, January 17, 1964). The Rolling Stones took more advantage of EP opportunities than most of their British Invasion rivals, issuing three of new material in the mid-’60s (and a maxi-single in the early ’70s). They could have used more imagination for the title of their first EP, but it was a good sampling of their early R&B repertoire, preceded by only two actual UK singles. The highlight, easily, was their soulful interpretation (complete with wavering but haunting background harmonies) of Arthur Alexander’s “You Better Move On,” the track primarily responsible for propelling this to #1 on the UK EP chart. As Roy Carr speculated in The Rolling Stones: An Illustrated Record, “Had it been released as a single, it may have well reached the very top.”

Also good was “Bye Bye Johnny,” a reliably energetic Chuck Berry cover. Less impressive was their rather murkily recorded version of “Money,” which was far inferior to the Beatles’ classic interpretation, and a routine run-through of the Coasters’ hit “Poison Ivy.” Perhaps these were attempts to be accessible to listeners likely to be more familiar with those songs than the relatively arcane blues that still featured in much of their repertoire. It wasn’t until late 1965 that “You Better Move On” came out in the US (on the December’s Children LP), and not until 1972 that “Bye Bye Johnny” and “Money” finally did so on the More Hot Rocks compilation.

“Poison Ivy,” meanwhile, didn’t come out in the US until the expanded CD version of More Hot Rocks in 2002. Note that the version of “Poison Ivy” on the 1972 More Hot Rocks collection (also included on the expanded CD) is a different, somewhat less impressive take, easily distinguished from the other by the presence of a guiro’s scraped percussive noises. It also fades out, where the harder-rocking EP version comes to a “cold” ending with a drum flourish. The weaker alternate version of “Poison Ivy” had first come out, I’m guessing by sloppy accident, on a UK various-artists sampler LP, Saturday Club.

The Downliners Sect, Nite in Gt. Newport Street (Contrast Sound Productions, January 1964). It was pretty rare that British Invasion bands released independent live EPs. Maybe there were some private pressings of such items here and there, but this four-songer is certainly the most widely known. Not that the Downliners Sect are too widely known–they never had a British or American hit. But they did put out three albums and a bunch of singles, and as something of a yet rawer Pretty Things (who themselves were something of a rawer Rolling Stones), they have their cult followers.

All four songs on Nite in Gt. Newport Street were American R&B covers, including routine workouts on Jimmy Reed’s “Shame, Shame, Shame” and Chuck Berry’s “Beautiful Delilah.” “Green Onions” doesn’t actually sound too much like the Booker T. & the MG’s classic, and hits a nice, slightly menacing loping groove. Their take on Bo Diddley’s “Nursery Rhyme” is really cool, laying down a solid Diddley beat behind effectively restrained vocals. I’m aware I’m not as much of a Downliners Sect fan as some other ’60s/British Invasion fanatics, but I think “Nursery Rhyme,” as early as it is in their career, is their best track, except maybe for “Sect Appeal” from their first LP.

This is a mighty rare disc, but all four cuts have long been easily available, as they were part of the 1994 compilation The Definitive Downliners Sect: Singles A’s & B’s. Not so for an unissued follow-up EP they recorded for Contrast Sound Productions. The four tracks (including covers of “Rock and Roll Music” and Jimmy Reed’s “Brite [sic] Lights—Big City”) came out in 2011 on the Brite Lights—Big City EP, which itself is now very hard to find.

Georgie Fame, Rhythm & Blue-Beat (Columbia, May 1964). Fame debuted a higher percentage of his output on EPs than most British Invasion stars, and maybe a higher one than anyone. Three EPs in 1964-65 presented a dozen tracks that hadn’t been available elsewhere—a whole album’s worth. Since he was a pretty big star in the UK after “Yeh Yeh” topped the British charts in January 1965, it’s strange he didn’t put out an LP that year. The same could be said of the Yardbirds, who had no British albums (although two were issued in the US) in 1965 either.

Rhythm & Blue-Beat is the first of those EPs, and is exactly what the title promises: Fame’s brand of jazzy R&B, married to a ska beat. It’s okay, but not up to the standard of his best mid-’60s work, and has a sort of novelty feel, especially on his adaptation of the “Humpty Dumpty” nursery rhyme (a live version of which had already come out on his debut album). He’d do another thematic EP of sorts in May 1965 with Fats for Fame, featuring four Fats Domino covers. In November of the same year, Move It on Over didn’t have a theme, though aside from the title track, it was devoted to R&B standards that were rather overdone by then (“Walking the Dog,” “High [sic] Heel Sneakers,” and “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu”).

The dispersal of numerous Fame tracks on EPs and non-LP singles, along with the usual discrepancy between his British and American discography, made assembling a complete collection of his pre-1967 material a difficult task indeed for decades. That was finally solved in 2015 by the expensive five-CD box The Whole World’s Shaking: Complete Recordings 1963-1966, which has everything from these EPs.

The Beatles, Long Tall Sally (Parlophone, June 19, 1964). Lots of Beatles EPs came out in their homeland in the first three years of their career, some of them big UK sellers. But Long Tall Sally was the only time they included tracks not previously available on UK albums or singles. It was a stormer, too, particularly the title cut, which had been a staple of Beatles shows almost since they began, and would be the last song they played at their last official concert (at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park on August 29, 1966). The other three tracks were hardly slouches, with John Lennon’s vocal pacing a terrific cover of Larry Williams’s “Slow Down” and Ringo taking one of his infrequent leads on Carl Perkins’s “Matchbox.” Rounding out the seven-inch was the sole original, “I Call Your Name,” a characteristically decent second-tier Lennon-McCartney tune.

Technically speaking, this didn’t mark the debut of all the tracks. Capitol Records, hungry for Beatles product after they invaded the US in early 1964, put “I Call Your Name” and “Long Tall Sally” on The Beatles’ Second Album, which had come out two months earlier. Also “I Call Your Name” had been the B-side of a Billy J. Kramer & the Dakotas single back in July 1963, though the Beatles’ own rendition slays it.

Even if you were one of the (likely very few) British residents who had The Beatles’ Second Album, however, on its own merits this was arguably the finest EP of the British Invasion. Perhaps it was an excuse to get some of their covers on disc without jamming up their albums with too much non-Lennon-McCartney material, but it’s none the worse for that. Likely they could have filled up several more EPs with more great covers if they’d had the inclination, but luckily quite a few of those were cut at their BBC sessions, and are now widely available on CD.

The Merseybeats, On Stage (Fontana, July 1964). Throughout early rock history, there were a bunch of releases by high-profile acts that gave the false impression they were recorded live. This is one of the more obscure ones, actually recorded in the studio, though the idea was to capture them more like they were on stage than their poppier singles did. The opportunity to record them in their native Liverpool’s Cavern Club was not taken advantage of, and it was, according to the Merseybeats’ Billy Kinsley, cut in a mere 25 minutes. All of the songs were covers, including “Long Tall Sally,” “I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Cry Over You” (which Elvis Presley had recorded early in his career), Jimmy Reed’s “Shame, Shame, Shame” (here just titled “Shame”), and Bo Diddley’s “You Can’t Judge a Book By Its Cover” (written by Willie Dixon). It was a major commercial success, making #2 on the British EP charts, on which it stayed for 25 weeks.

It would be great to report this shows the Merseybeats could have been a tough rock/R&B act given the chance, but in fact the results are mostly mediocre. Actually, “Long Tall Sally” and “Shame” have terrible throaty, rasping lead vocals, a kazoo (!) on “Shame” adding another irritant. Perusing the detailed liner notes of a couple Merseybeats reissues doesn’t reveal who was responsible, though according to Spencer Leigh’s It’s Love That Really Counts: The Billy Kinsley Story, it’s drummer John Banks on “Long Tall Sally,” and (the text seems to infer) Aaron Williams on “Shame.” As the Beatles’ own ace version of “Long Tall Sally” had come out only slightly earlier, the one by the Merseybeats can’t help but sound ghastly in comparison.

“I’m Gonna Sit Right Down and Cry Over You,” at least, is fairly good—not nearly as good as the Beatles’ terrific 1963 BBC version, but then that would not have been available for contrast back then. “You Can’t Judge a Book By Its Cover” is fair at best, and no match for the best Diddley covers by the likes of the Rolling Stones and Pretty Things. In truth the Merseybeats were really more suited for pop-rock, and made some fairly good (though hardly great) singles in that vein, though they never had US success.

All four tracks from this EP, and everything else they did in the ’60s, are on the 2002 Bear Family compilation I Think of You: The Complete Recordings. According to the Merseybeats’ Tony Crane, On Stage was the third best-selling British EP of 1964, “only beaten by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones,” though I have a hard time believing there weren’t more than a couple Beatles and Stones EPs that outsold it.

The Rolling Stones, Five By Five (Decca, August 14, 1964). Having cut some fine sides at Chess Records’ studios during their first US tour, the Stones were eager to get some of them out before their second full-length UK album. Devoted mostly to covers, 5 X 5—with, as the title suggested, five tracks rather than the more common four—was a fine dish of those, from the time they were still a very R&B-oriented band. Their rendition of Chuck Berry’s “Around and Around” (the very first song Mick Jagger and Keith Richards had performed in public) was the most popular. But the instrumental “2120 South Michigan Avenue” (named after the address of the Chess studios) was the best, as kind of a more rock-oriented take on Booker T. & the MG’s with a compelling riff and great Ian Stewart organ (and some of Bill Wyman’s best bass).

Also on the EP were a contemporary soul cover (of Wilson Pickett’s “If You Need Me”) and a slow blues (“Confessin’ the Blues”), both well done. Their songwriting was still in a relatively primitive stage on the one original, “Empty Heart,” but even that had some cool irregular rhythms and wayward backing vocals. American fans wouldn’t miss out on these cuts for long, as they formed the backbone of their second US album, 12 X 5, just a couple months later. To quote Roy Carr’s The Rolling Stones: An Illustrated Record again, “Along with the Beatles’ Long Tall Sally four-tracker, Five By Five is unquestionably the first and last great EP. They really don’t make records like these any more.”

Another collectors’ note: a longer version of “2120 South Michigan Avenue” came out on a German LP compilation, with markedly more guitar soloing by Keith Richards. That was finally made available in the US on the 2002 CD of 12 X 5.

The Rolling Stones, Got Live If You Want It! (Decca, June 11, 1965). The Rolling Stones’ first live release had rather lo-fi recordings from their March 1965 UK tour. If not the Stones as their early very best, it’s still a fun and atmospheric (for the wild screaming) listen. Three of the songs (“Route 66,” “Pain In My Heart,” and a very abbreviated “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love”) had been on their first couple British LPs in different studio versions. But the two others, Bo Diddley’s elemental “I’m Alright” and Hank Snow’s “I’m Moving On,” were not otherwise issued by the Stones. “I’m Alright” is exciting and “I’m Moving On” is easily the EP’s high point, with fine slide guitar and harmonica, in a hard-driving arrangement not too similar to either Snow’s country original or Ray Charles’s soul cover.

Got Live If You Want It! caused more than its share of discographical confusion among collectors. First, the US album Got Live If You Want It!, issued in 1966 (and not issued in the UK), is an entirely different recording. It does have a lamer version (with the original backing track, but re-recorded vocals) of “I’m Alright,” which had appeared in its original EP version on the American 1965 album Out of Our Heads. Two of the other tracks, “I’m Moving On” and “Route 66,” found their way onto the grab-bag late-’65 American Stones LP December’s Children. “Pain in My Heart” and “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love,” meanwhile, didn’t get released in the US until the 2004 box set Singles 1963-1965 (although these had been on an EP, not a single).

Finally, “We Want the Stones,” listed as a “song” on the original release, is in fact nothing more than a crowd chanting “we want the Stones,” lasting thirteen seconds (and credited to the band’s pseudonym for group compositions, Nanker Phelge). That’s on Singles 1963-1965 too. As for the title, “Got Live If You Want It” is a pun on the Slim Harpo blues classic “Got Love If You Want It,” which had already been covered by the Yardbirds and the Kinks, though the Stones never put out a version.

Manfred Mann, The One in the Middle (HMV, June 18, 1965). Manfred Mann utilized the EP format to debut tracks more than most major British Invasions did. I’m just choosing one here since some of them weren’t that interesting (particularly the EPs of instrumentals), and/or the tracks often soon appeared on other releases. For the record, the January 1965 EP Groovin’ with Manfred Mann had a dynamite Ben E. King cover in the title track and a couple fair R&B rockers with “Did You Have to Do That” and “Can’t Believe It,” But all were on the US The Five Faces of Manfred Mann LP a couple months later, and the fourth track on the EP was “Do Wah Diddy Diddy,” which had already been a #1 single.

The One in the Middle was their most interesting EP, though one track, “Watermelon Man,” had been on the American LP The Five Faces of Manfred Mann. “The One in the Middle,” a self-referential Paul Jones composition detailing the roles of the Manfreds (though he originally intended it for Yardbirds lead singer Keith Relf), was the song most responsible for the disc topping the British EP chart. Quite possibly it could have been a hit British single on its own, though Manfred Mann were in the midst of a lengthy bunch of those. Just as notable was their cover of Bob Dylan’s “With God on Our Side,” which had an almost orchestral buildup (without orchestral instruments) that gave it a power and feel quite unlike the plaintive folk original.

In this company, their cover of the Paris Sisters’ “What Am I To Do” was lightweight, though it’s worth noting that it’s not only a catchy pop-rocker, but is also far better than the timorous original. It, “With God on Our Side,” and “The One in the Middle” all appeared Stateside in October 1965 on the My Little Red Book of Winners LP.

The Kinks, Kwyet Kinks (Pye, September 17, 1965). Contrary to the title, the four songs on this EP weren’t that much quieter than the Kinks’ usual early fare. Most of them were folkier, though, and one in particular marked the first major departure of main singer-songwriter Ray Davies into social commentary. That was “A Well Respected Man,” which became a deserved big US hit when it was issued in the US the following month. It’s a rare example of a British Invasion band and/or label misjudging the singles market, since it was–to this day, to the surprise of some British Invasion fans—not issued as a 45 in their home country.

The other songs on this EP might not have been up to that level, but a couple were certainly good. Dave Davies had his first major outing for his folky tendencies as singer and songwriter of the pleasing midtempo “Wait Till the Summer Goes Along,” which had a rambling country-folk feel. Ray Davies had a decent, and still largely overlooked, folk-rockish outing with “Don’t You Fret,” which almost sounded like a Scottish or Irish ballad given a couple tense rave-up accelerations. “Such a Shame” was much more ordinary (if rather downbeat) British Invasion pop, but three out of four on an EP of previously unavailable originals is pretty good.

Part of the reason this EP doesn’t get much comment outside of the UK is that all of the tracks were quickly available on US releases. “Such a Shame” showed up on the B-side of the American “A Well Respected Man single, and all four songs were on the US Kinkdom album just a couple months after the EP came out across the Atlantic.

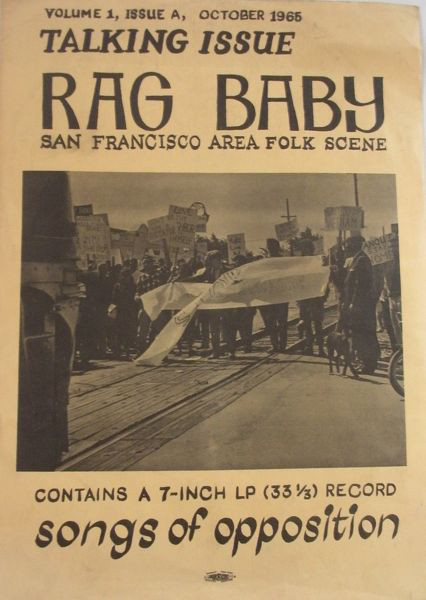

Country Joe & the Fish, Talking Issue #1 (Rag Baby, October 1965). Distributed with the underground Rag Baby magazine, this might be of more historical importance than musical brilliance, but its position in Bay Area rock history is notable. This early version of Country & the Fish—Joe McDonald and guitarist Barry Melton were the only musicians who’d go on to the fully electric Fish—was more jugband folk than rock, though Melton did play electric guitar. Also, this EP has just two tracks (all of side one) by the group on the disc. The flipside has two forgettable folk songs by Peter Krug, who wasn’t in the Fish.

But the two Fish songs are early versions of a song that would feature in a full rock arrangement on their first album (“Superbird”) and, more notably, an early version of their most famous number, “I Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag.” These are barer and considerably less effective than the re-recordings. Yet they’re among the earliest relics of Bay Area protest rock, which would grow more psychedelic as folkies like McDonald and Melton made the transition to loud electric instruments. They did so fully by the time of their second, far more impressive EP in 1966, also listed here.

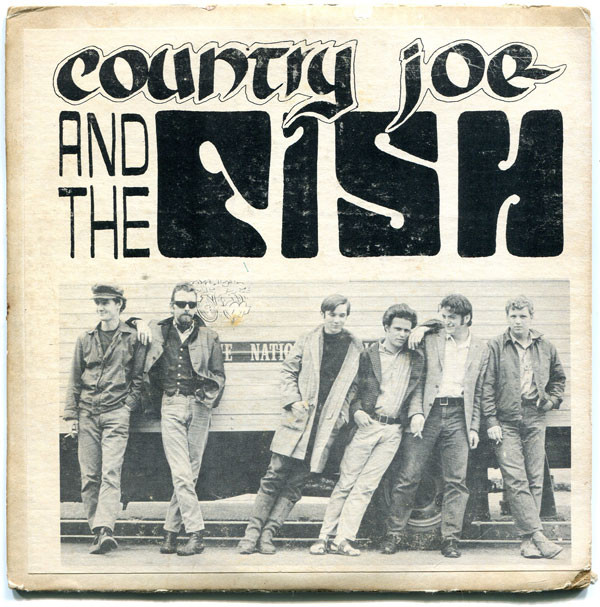

Country Joe & the Fish, Country Joe & the Fish (Rag Baby, July 1966). While this features a slightly different lineup than Country Joe & the Fish would have slightly later when they recorded their debut album, this is all-out electric rock that counts among the first truly psychedelic recordings from the San Francisco Sound (though to be technical, the Fish were based in Berkeley). All three of the songs would be re-recorded for their first LP, and all are in somewhat less polished state here, though not much if at all to their detriment. These include “Thing Called Love,” which would be retitled “Love” on the album, and “Bass Strings.”

But the piece de resistance of the EP—if not of the Fish’s whole career—is the nearly seven-minute instrumental “Section 43.” It’s one of the greatest psychedelic instrumentals, blending hypnotic Asian-influenced melodies, spooky ethereal organ, fiercely distorted electric guitar, and even a bit of bluesy raveup and jugband hijinx. The remake on the debut Electric Music For the Mind and Body album is similar, but not as good or spontaneous. Country Joe & the Fish can also be seen performing this, to great effect, in the Monterey Pop movie.

It will never be possible to get accurate statistics, but this could have been the highest-selling and most influential self-released EP of the 1960s. Figures as high as 15,000 copies have been quoted for its total sales, and it was reportedly distributed in underground record stores and head shops well beyond the Bay Area, as far away as Europe. Original copies are now rare and expensive, but fortunately both this and the Fish’s 1965 EP (as well as a less impressive 1971 EP where McDonald was the only remaining musician) were compiled onto the 1980 LP Collectors Items: The First Three EPs.

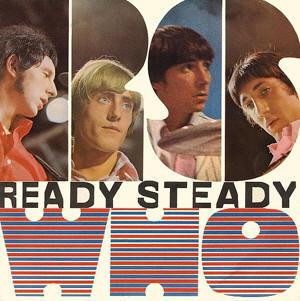

The Who, Ready Steady Who (Reaction, November 11, 1966). A kind of weird mix of throwaways and quality originals, the inspiration behind the title of this five-song EP would have been mostly unknown in the US, where the UK rock TV show Ready Steady Go! wasn’t broadcast. It might have led fans to think these were performances from that program, but in fact they were studio tracks, not live (or even “live in the TV studio”) recordings. If only in hindsight, side two seems like a vehicle to let Keith Moon get his surf fanaticism out of his system, with a cover of “Barbara Ann” and Jan & Dean’s much more obscure “Bucket T.” Also on side two was a short (one minute and 22 seconds) and strange cover of “Batman,” also done (though briefly as part of a medley) on the live LP the Kinks did in 1967.

Side one, though, had some good Pete Townshend originals. “Disguises” was a really good mod rock tune that, in line with their 1966 UK hits “Substitute” and “I’m a Boy,” were subtle evocations of how things weren’t always what they seemed. It’s not as good as those two hits, but it’s not too far out of that league either. A considerably different version of the good power-popper “Circles” had been on the US version of their debut My Generation LP, and different sources have given different accounts of how the two versions circulated. This is what I can gather: the one on the American My Generation was produced by Shel Talmy. The second one, produced by the Who without Talmy, came out on the B-side of the original “Substitute” single, but had to be withdrawn because the group and Talmy were in a legal dispute.

It seems like this second version is the same as the one on Ready Steady Who, and thus the only one of the five tracks on the EP to have already been available, if briefly. I don’t have that original rare withdrawn 45, and if that’s not accurate, feel free to send in corrections. In any case, I prefer Talmy’s version, which though it has a kind of murky mix, has more energy than the one on the EP. The EP take is considerably cleaner, but more reserved.

“Disguises” was first heard in the US when it made the Magic Bus compilation LP in 1968, which also, kind of inexplicably, included “Bucket T,” one of their strangest early efforts (particularly in John Entwistle’s goofy horn solo). It took a while for the other tracks to become available Stateside, “Barbara Ann” appearing on 1986’s Who’s Missing, and “Circles” coming out on 1987’s Two Missing compilation. “Batman” made it onto the 1995 expanded CD of the Who’s second album (A Quick One), whose bonus tracks also include three other songs from the EP—but not the EP version of “Circles.” Is it any wonder Who fans resorted to bootlegs to get the five tracks, both because it took so long for all of them to appear on US releases, and because even when they did they were scattered here and there?

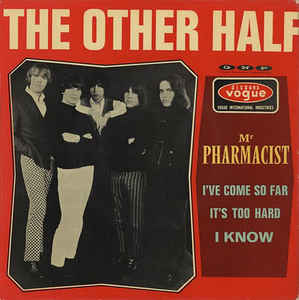

The Other Half, The Other Half (Vogue, January 1967). Sometimes tracks showed up on foreign EPs for inexplicable reasons that will probably never be known. Such was the case with the Other Half, a very good but obscure California group that bridged the gap between garage rock and psychedelia. Their best known song might be their first single, “Mr. Pharmacist,” the A-side of the only 45 they did for GNP Crescendo (more famous for their Seeds releases). That’s on this four-song French EP, along with its B-side, “I’ve Come So Far.”

But the EP also has two songs, “I Know” and “It’s Too Hard,” that never came out in the US. Since the Other Half never had anything close to a hit in their home country, it’s kind of baffling as to why Vogue, a very prominent French label, would license unreleased tracks by an unknown American band. It’s a good thing they did, though, since like the ones on the GNP Crescendo, they’re fine if slightly raw moody garage-psych tunes, paced by the brilliant sustain-laden guitar of Randy Holden.

More than even most good obscure bands of the era, the Other Half have had bad luck in getting their legacy properly enshrined on reissues. All four songs from the EP were included on the 1982 French LP Mr. Pharmacist (which also had all the songs from their good self-titled 1968 LP, as well as the non-LP B-side “No Doubt About It”). Most of the CD reissues of this material are designated “unofficial” in discogs.com.

There are other instances, by the way, of tracks mysteriously showing up on French EPs only, most famously (at least among the people who trace this sort of thing) an alternate version of the Who’s “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” A French EP by the Belfast Gypsies, a good spinoff group of Them, had an instrumental (“The Gorilla”) not found elsewhere, though it turns out it wasn’t even recorded by the Belfast Gypsies, but by a different unidentified band. And there’s another example in our next entry.

We the People, St. John’s Shop (London, January 1967). We the People were a good, not great, Florida group who put out some pretty good singles that encompossed both gnarly garage rockers and melodic ballads with a Zombies influence. They had some regional success, but never charted nationally. Which makes it all the more mysterious, a la the Other Half EP, why some unreleased tracks of theirs showed up on a French EP. One of these four tracks (“In the Past,” a garage-psych gem that ranks as their best recording) came out in the US on a single near the end of 1966, but the other three didn’t come out on American discs. One, “Declaration of Independence,” was pretty good and about on the level of their better 45s; another, “Lovin’ Son of a Gun,” is a so-so midtempo bluesy rocker.

But the title track is one of their best numbers, with its slightly psych-addled Zombies wistfulness (“you may think his way is way out, but his way is in”). What’s more—at least from what I can gather from what’s been written about We the People—it was a string-less version, minus the orchestral overdubs that diluted the cut when it was issued on a US 45. Here’s guessing it might never have come out had it not leaked onto this French EP. Fortunately all four of the tracks were made widely available on CD decades later.

John Mayall’s Bluebreakers with Paul Butterfield, John Mayall’s Bluebreakers with Paul Butterfield (Decca, January 6, 1967). Pairing good rock musicians with each other doesn’t necessarily result in something twice as good, and in fact often doesn’t result in something as good as what they were doing on their own. Such was the situation with this four-track EP, putting together arguably the most important mid-’60s blues-rock bandleaders of the UK and the US. Both Mayall and Butterfield had made justly famous and influential albums in 1966, but this joint effort is surprisingly ordinary and unmemorable, if competent. There aren’t any major flaws, but there aren’t any huge sparks either.

Some more original material might have helped; just one of the tracks here, Mayall’s “Eagle Eye,” falls in that category. Giving more space to Peter Green for the kind of fiery guitar work found in the 1966 Bluesbreakers album with Eric Clapton, and Butterfield’s 1966 East-West LP with Mike Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop, could have lit some fire too. Note that while this EP is sometimes titled All My Life in discographies, no title is given on the record’s artwork.

Somehow I found an original copy of this EP, which I’d presumed quite rare and hopeless to count on finding, at Rhino Records in Los Angeles in the mid-1980s for just five dollars. I suppose that had something to do with the poor condition of the sleeve (the top had come unglued and there were some stains on the back), though the disc plays well. All four tracks have come out as bonuses on CD reissues of the A Hard Road album, which Mayall had recorded with Green and the Bluesbreakers shortly before cutting this EP.

Mad River, Mad River (Wee, late 1967). If not a name as big as most on this list, Mad River were one of the better San Francisco bands that didn’t make it nationally in the late-’60s, recording two albums for Capitol. The first of these (also, like this EP, self-titled) is odd, tense, dark psych with some gnarly guitar. I don’t like the second, the country-rock-oriented Paradise Bar and Grill, nearly as much, but it has its devotees. Even some psychedelic rock fans who know about both LPs, however, don’t know the group did an earlier three-song EP for a small Bay Area label.

Its value is diminished a little since two of the three songs, “AGazelle” and “Windchimes,” were redone for their first LP (as “Amphetamine Gazelle” and “Wind Chimes”), though the EP arrangement of “Wind Chimes” has some “hare krishna” chanting that didn’t survive into the later version. But the third track, “Orange Fire,” was not featured on their albums in any guise. While some collectors are prone to saying “and this non-LP cut was their best song” more because it’s rare than because it’s decisively better, in this case, “Orange Fire” was their best song. An eerie folk-rock ballad for the most part, it offered some of the most direct, blunt anti-Vietnam War protest of any rock recording. I say “for the most part” because a couple times it erupts into fierce instrumental breaks with cacophonous crossfire of distorted guitars, as if to sonically mirror the carnage of the Vietnam War.

It’s mystifying as to why “Orange Fire” didn’t find a place on their first Capitol album. While I doubt it was a factor, it can be pointed out that some of the chording in the instrumental sections strongly recalls riffs that have a prominent role in the Yardbirds’ psychedelic classic “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago.” The original EP, though it got some local sales and airplay, is impossible to find. Fear not—like a couple other Bay Area rarities discussed in this post, it’s on the CD compilation The Berkeley EPs.

The Move, Something Else from the Move (Regal Zonophone, June 21, 1968). This five-song disc had a significant plus and minus. The plus was that none of the five, all recorded live at London’s Marquee club (though some had “new live vocals…recorded at Marquee studios”), appeared in any version on their studio LPs and singles. The minus was that they’re not as interesting as their many good studio tracks, in part because they’re all covers.

At least it’s certainly not a run-of-the-mill choice of material, including the Byrds’ “So You Want to Be a Rock’n’Roll Star,” Love’s “Stephanie Knows Who,” Eddie Cochran’s “Something Else,” Jerry Lee Lewis’s “It’ll Be Me,” and Spooky Tooth’s “Sunshine Help Me.” The Love cover’s the best, but generally they’re sort of undistinguished versions, and it’s kind of like hearing a BBC session where a group takes the opportunity to do favorites by others they’re not intending to do in the studio. (The group did quite a few of those on the radio too, as heard on some archival releases.)

Surprisingly, the EP wasn’t hard to get as a twelve-inch reissue back in the early 1980s. A 1999 reissue added bonus tracks from the same event, again all covers, including “Piece of My Heart,” Jackie Wilson’s “Higher and Higher,” a second version of “Sunshine Help Me,” and–most surprisingly—”Too Much in Love,” from an obscure 1968 Denny Laine single. A 2016 expanded CD puffed it up more with live 1968 Marquee versions of their UK hits “Fire Brigade” and “Flowers in the Rain,” a cover of the Everly Brothers’ “The Price of Love,” and a very brief “Move Bolero.”

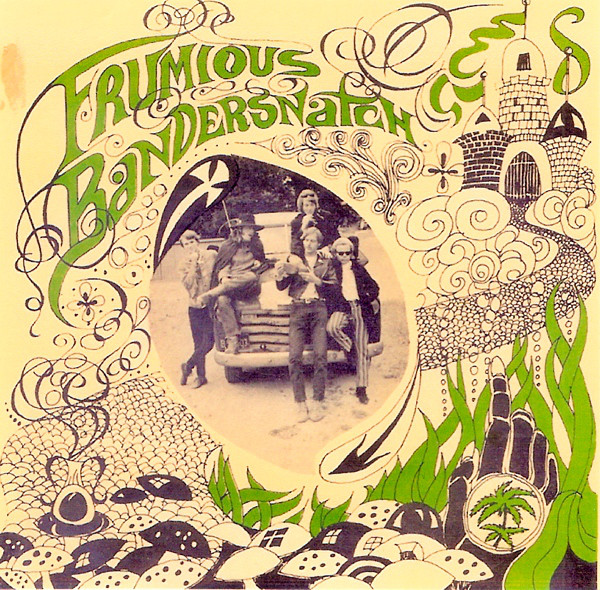

Frumious Bandersnatch, Frumious Bandersnatch (Muggles Gramophone, June 1968). One of many San Francisco-area psychedelic bands who barely or never got the chance to record, Frumious Bandersnatch did put out a three-song seven-inch—not skimping on running time, with fourteen minutes of music—in mid-1968. More so than most of the entries on this list, it had an “easily the highlight” track in the dramatic, captivating “Hearts to Cry,” with excellent Quicksilver Messenger Service-like guitar, haunting vocal harmonies, and a midsection raveup. On the basis of this track alone, they seemed to have potential that was deserving of at least a full album. The other two tracks were not as memorable, but not dispensable either.

Pressed on purple vinyl with a picture sleeve, this is mighty rare in its original incarnation. Fortunately this, like Country Joe & the Fish’s second EP and Mad River’s EP, is on the 1995 CD The Berkeley EPs, which also includes a less impressive rare EP from the region by Notes from the Underground. That collection (along with Country Weather’s one-sided LP) serves as evidence that the San Francisco psychedelic scene, and particularly bands that were sometimes based in the East Bay, generated more in the way of notable EPs than anywhere else in the US. Fortunately much other Frumious Bandersnatch material, which was unreleased at the time, became available on the 1996 CD compilation A Young Man’s Song. “Hearts to Cry” still stands out as their best song by far, however.

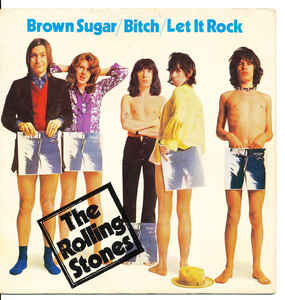

The Rolling Stones, “Brown Sugar”/”Bitch”/”Let It Rock” (Rolling Stones, April 26, 1971). One anomalous early-’70s/maxi-single entry tops off this list. On their own, “Brown Sugar”/”Bitch” made for a tremendous double-sided single. In the UK, a live cover of Chuck Berry’s “Let It Rock” was added to make it a three-song “maxi-single.” That cover’s a reliably decent Stones interpretation of a Berry standard, though not one of Berry’s greatest songs or among the Stones’ best Berry covers.

And an honorable mention for the most interesting unreleased EP:

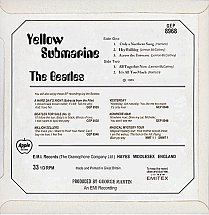

The Beatles’ Yellow Submarine album is justly considered the least essential LP they released while active that was centered around “new” material. Released in January 1969, this soundtrack to their animated feature actually only contained four previously unreleased Beatles songs, and even those were leftovers from sessions in 1967 and early 1968. Side one of the LP was filled out with “Yellow Submarine” and “All You Need Is Love” (both of which were featured in the movie), neither of which were hard to get elsewhere then or since. Side two had instrumental George Martin music for the film score that might have defenders here and there, but realistically, few listeners have played that side more than once or twice.

At the time and since, the Beatles and EMI have been criticized for putting so much filler on a full-length (and full-price) LP. A subsequent CD reissue titled Yellow Submarine Soundtrack improved matters by getting rid of the Martin score and adding nine actual Beatles songs that had been used in the film soundtrack (although all of those, like “All You Need Is Love” and “Yellow Submarine,” had been previously available on other discs).

What could and should have been done at the time of the film’s premiere in July 1968 was to put out an EP of the four previously unreleased songs, adding another outtake. In fact such an EP was given initial preparation for release, though not until March 13, 1969. On that date, a master tape for a five-track EP was compiled and banded at EMI. Side one would have featured “Only a Northern Song,” “Hey Bulldog,” and “Across the Universe.” Side two would have presented “All Together Now” and “It’s All Too Much.”

“Across the Universe” actually hadn’t been on the Yellow Submarine album or soundtrack. It would find a home on the No One’s Gonna Change Our World various-artists charity album in December 1969. With some overdubs, a different Phil Spector-produced version would appear on Let It Be.

The release of this five-track EP back in March 1969 would have made perfect sense, though it might have ticked off the millions of fans who’d already paid full price for the Yellow Submarine LP sans “Across the Universe.” Actually it would have made yet more perfect sense to put out the EP back in July 1968, though that might have ticked George Martin off. This would-be EP, incidentally, was mastered in mono, though that format was going into obsolescence by early 1969.

So was the EP format itself, but actually the Beatles had used it for a new release fairly recently. Magical Mystery Tour was released as a double EP in the UK. In the US, it came out as an LP with the six songs from the UK double EP (all of which had been on the TV program’s soundtrack) and the five songs from 1967 singles that hadn’t been on LP. In that case, the full-length LP presentation actually made more sense, even if it had five songs that weren’t on the soundtrack.

If the Beatles ever get on board Record Store Day’s fashion for vinyl releases of classic material, don’t be surprised if that canceled Yellow Submarine EP finally sees the light of day. In mono, of course.