Shohei Ohtani. What can you say about the 2021 American League MVP that hasn’t been said already? Which doesn’t stop broadcasters and pundits from repeating a variation of that sentence ad infinitum. Even some people who aren’t baseball fans might know that in 2021, he almost became the first guy to have both ten wins and ten home runs in a season since Babe Ruth did it a little more than a hundred years ago, in 1918. Which would have made him the only guy besides Ruth to have done that. Actually Ohtani had nine wins and forty-six home runs, though unlike Ruth, he seldom played in the field when he wasn’t pitching.

(Important note: Almost one year after this post was written, Ohtani did become the first player since Ruth to win ten games and hit ten homers in a season when he won his tenth game of 2022 on August 9. He also hit his 25th homer of the year in that game. Also note that two players from the Negro Leagues, Bullet Rogan of the 1922 Kansas City Monarchs and Ed Rile of the 1927 Detroit Stars, also accomplished this feat.)

It’s not often been mentioned, however, that there are a couple of other guys who’ve both won ten games in a season and hit ten home runs in a season, though not in the same year. One of them’s the only player besides Ruth to both win twenty games and hit ten home runs in separate years. Another’s the only guy besides Ruth to both win ten games and hit twenty home runs in separate years. There are a few other guys who came close to notching double figures in both wins and home runs, one in the same year.

One of those other men pulled off the double-double, if you want to call it that, fairly recently. As a rookie, Rick Ankiel showed great promise in 2000 for the Cardinals, going 11-7 in thirty starts with a 3.50 ERA and striking out 194 batters in 175 innings. Rather infamously, he melted down in the 2000 playoffs, with stats that still astound – four innings pitched in three games and two starts, a 15.75 ERA, eleven walks, and nine wild pitches.

These were the early days of being able to follow a game online if you couldn’t watch it or hear it on the radio, and I still remember wondering if the site relaying the play-by-play was having a meltdown by displaying wild pitch after wild pitch. No, it really happened. And Ankiel never regained adequate control, though he pitched a few more games in the majors. His 2001 minor league Triple A stats are particularly gruesome—4.1 innings, seventeen walks, and twelve wild pitches—and though some low-minor stints went much better, in a few years he decided to concentrate on trying to make it back to the bigs as an outfielder.

That went pretty well, and in 2008 he hit 25 homers as a Cardinal. He didn’t sustain that success, in part due to injuries, and finished with 76 career home runs—the only man besides Ohtani and Ruth to win more than ten games and hit more than 70 homers, as Wikipedia will tell you. Would he have been a better hitter, or star, had he focused on hitting and fielding from the beginning? We won’t know, though his overall unspectacular record suggests he wouldn’t have been an all-star.

The other man to have double-digit seasons in both the home run and win column is much more obscure. As a rookie, Reb Russell went 22-16 for the White Sox in 316 innings, with a 1.90 ERA. Norms were much different for pitchers in the dead ball era, of course, but that’s still an impressive start. Russell also won 18 games for the Sox when they won the World Series in 1917, and started one of the series games, but was pulled after failing to retire a batter. He wasn’t given much of a shot, getting relieved after just three batters – a walk, single, and double. (Which is, by the way, another rabbit hole baseball trivia question: how many starters were pulled from World Series games without recording an out? See the end of this post for some follow-up.)

Back to Russell: he’s one of the most obscure members of the Black Sox, pitching to just two batters in one June game (retiring neither) in 1919. He’d been a good if unspectacular hitter for a pitcher, with ten triples in White Sox uniform. Like Ankiel, he also converted to outfield and worked his way back to the majors by hitting well in the minors. When he played for the Pirates in the final months of 1922, he played better than well.

Get a load of this stat line: 60 games, 12 home runs, a .368 batting average, a .668 slugging average, and 75 RBI. Over 150 games, that works out to 187 RBI, which threatens Hack Wilson’s all-time record of 191. Sure, that’s inflated by the conditions of the early 1920s, a boom time for hitting, but even relative to those, that’s stunning. Could he have been a bigger star if he’d been an outfielder all along?

Russell didn’t even get much more of a chance in the majors. He was 33, and while he did get a fair amount of playing time in 1923, his stats fell back to ordinary status, though he did hit nine home runs. Had he hit one more, he would have joined Ruth and Ankiel as the only players to have both ten-win and ten-homer seasons more than once. He didn’t play in the big leagues again, defensive limitations also being a factor, though he hit well in the minors the rest of the 1920s.

Who’s the closest to pulling off a double-double without quite managing it? Fairly famously, Wes Farrell holds the record for home runs in a season by a pitcher—nine, in 1931 with Cleveland. He also holds the record for home runs in games in which the player is a pitcher—37 (he had 38 lifetime, but one was as a pinch-hitter). He was a pretty good pitcher too, with 193 lifetime wins, and six seasons where he won twenty or more. One of them was 1931, when he won 22 games besides bashing those nine homers.

Ferrell seemed headed for a Hall of Fame career, but developed arm trouble as he entered his thirties. I once read it suggested that Ferrell would have been a Hall of Famer had he been an outfielder, and he did try to play outfield for about a dozen games in 1933 while maintaining his career as a pitcher, though that was soon abandoned. I’m not so sure about that.

While he was undoubtedly the best-hitting pitcher in history who primarily played games as a pitcher, it’s a little curious he—unlike Ankiel, Russell, and a couple others we’ll soon get to—didn’t make it back to the majors as a position player after his pitching career ended. He did play as an outfielder for a few years in the low minors in the 1940s before and after the war, putting up some awesome numbers—a .425 BA with 24 homers and .766 SA in class D in 1948, for instance, at the age of forty. Maybe he was too committed to pitching to make a relatively quick conversion after his arm troubles, or maybe considered too old to advance once he’d started tearing up the low minors as a hitter.

There are a couple other guys who didn’t miss the double-double by much—one pretty well known, one not so well known. Smoky Joe Wood, like Ferrell, seemed on track for a Hall of Fame career after going 34-5 with a 1.91 ERA with the Red Sox when they won the World Series in 1912, aged just 22. He hurt his arm the next year and, while effective with a much reduced workload the next three years, barely pitched after 1915.

But he was a good-hitting pitcher—.290 in the year he won 34 games, with 13 doubles. In 1918 he came back to the minors with Cleveland as an outfielder and, if not exactly a star, did okay, hitting .366 as a part-timer in 1921. The next year, as a regular, he hit .297 with eight homers—not star material by early-‘20s standards, but alright. He probably had some baseball left in him and maybe could have had a shot at hitting ten home runs in a year. But as he told it in The Glory of Their Times, “Could have played there longer, too, but I was satisfied. I figured I’ve proved something to myself. So in 1923 when Yale offered me a position as baseball coach at the same salary as I was getting from Cleveland, I took it. Coached there at Yale for twenty years.”

Also getting a chapter in The Glory of Their Times was the far less famous Rube Bressler. As a nineteen-year-old rookie pitcher with the 1914 Philadelphia Athletics, he was outstanding—10-4 with a 1.77 ERA, though he didn’t get to pitch in the World Series, which they lost to the Braves. A’s manager Connie Mack notoriously sold off most of his star players after the Series loss, and in 1915 the team fell to last, Bressler contributing with a 4-17 record and 5.20 ERA. It looked like he was on his way back by going 8-5 with the Reds a couple years later, but he didn’t pitch much after that. He got into some games with the 1919 Reds, but didn’t pitch in the World Series, which they won over the Black Sox.

Yet by then he was playing more in the outfield than the pitcher’s mound. By 1921 he was just a position player (sometimes at first base), and nearly a regular, hitting .307 in just over a hundred games. While he wasn’t a star as a semi-regular for the Reds during much of the 1920s, he was okay, and had a lifetime .301 average with 1170 hits. In 1924-1926 he posted averages of .347, .348, and .357, helped by conditions that inflated batting averages to historic proportions throughout the majors. He never had much home run power, but he did have nine in 1929, just missing double figures.

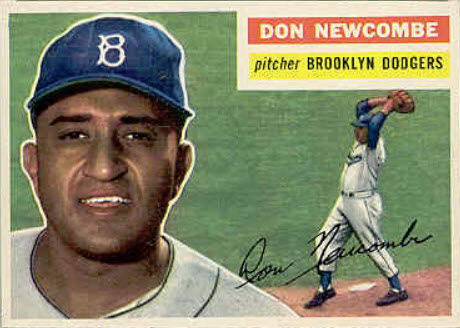

An honorable mention should be given here to Don Newcombe, one of the first outstanding African-American major league pitchers. Besides winning 153 games (mostly for the Dodgers, including three years when he won twenty or more), he was one of the best-hitting pitchers of his or any era. In 1955, besides going 20-5, he hit .359 with seven homers, nine doubles, a triple, and 23 RBI in 117 at-bats. Wrote Bill James in The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, “That was, with the exception of one Wes Ferrell season and Babe Ruth, the best-hitting season by a pitcher in the twentieth century.”

After wrapping up his big league career at the beginning of the 1960s, Newcombe played one season in Japan. However, he only pitched one game, playing outfield or first base the rest of the time. In about a half season (81 games), he held his own, hitting 12 home runs to go with a .473 slugging percentage. If you consider the Japan Central League a major league, that means he hit double figures in wins and homers in two different seasons – in fact, that he both won twenty games in a year and hit ten homers in a different one. In fact, that would make him the only player to win 25 in a year (he won 27 in 1956) and ten in a different year. Even Babe Ruth didn’t do that.

(Back to a question posed earlier: how many starters besides Reb Russell were pulled from World Series games without recording an out? There were four. Harry Taylor of the Brooklyn Dodgers faced four batters (two singles, a walk, and a fielder’s choice) without getting an out in the fourth game of the 1947 series. That game’s famous, for an entirely different reason. It’s the one where Yankee pitcher Bill Bevens had a no-hitter with two outs in the ninth, only to lose the no-hitter and the game on Tommy Henrich’s two-run double. And neither Taylor nor Russell, by the way, ever pitched in another World Series game, thus never retiring a batter at all in World Series competition.

Another World Series starter not to retire a batter was Hank Borowy, who faced three batters in the final game of the 1945 World Series, giving up singles to each of them. There were extenuating circumstances. After starting games one and five for the Cubs against the Tigers, he pitched the last four innings of a twelve-inning game in relief the day after game five to get the win. Then, just two days after game six, he started game seven, and didn’t have much left on such short rest. He’s one of the few pitchers to get four decisions in a World Series, winning two and losing two. Another, Red Faber, was a teammate of Reb Russell in the 1917 World Series, when he went 3-1, winning the game that Russell started.

And there’s another 1917 game in which a starting pitcher didn’t retire a batter that’s fairly famous, and involves another guy in this survey. On June 23, 1917, Babe Ruth walked the first batter against the Senators, and was thrown out of the game for arguing with the umpire. He was relieved by Ernie Shore, who, after the runner who’d walked was thrown out stealing, retired the next 26 batters in a row. For many years this was considered a perfect game, though now it isn’t officially classified as one.)

Two other less colorful World Series games in which the starter didn’t record an out were Charlie Root in 1935 and Bob Welch in 1981. Charlie Root, more famous as the pitcher who gave up Babe Ruth’s legendary called-shot homer in the 1932 series, gave up four hits and four runs as the starter against the Tigers in game 2 in 1935. Root was a decent pitcher who won 201 regular season games, but was bad in the World Series, with a lifetime record of 0-3 and a 6.75 ERA in four series for the Cubs (all of which they lost) between 1929 and 1938. He was also the starting pitcher in the famous game 4 of the 1929 World Series when the Cubs lost an 8-0 lead to the A’s (and eventually the game, 10-8) when they gave up ten runs in the seventh inning, though Root wasn’t on the mound long enough that inning to get charged with the loss. Welch gave up three hits, a walk, and two runs in game 4 of the 1981 series against the Yankees, though his Dodgers actually won that game 8-7, though they lost the series.