About a month ago, it was reported that the San Francisco Giants and Oakland A’s might share the Giants’ stadium, AT&T Park, for a while in the future. That might happen if the A’s build a new stadium in Oakland (not at all certain since ownership has looked at relocating to San Jose, the East Bay suburb of Fremont, and other options over the last few years) and need a temporary home in the meantime. Why not just keep playing at their current home (the Coliseum, now officially O.co Coliseum) in Oakland, you ask? Well, would you want to play in a ballpark where sewage backs up in the clubhouse, as it did yesterday during a rainstorm canceling the A’s’ last exhibition game?

As a San Francisco resident, I’d kind of like having both teams in AT&T Park, at least for a year or two. That wouldn’t make my East Bay friends happy, as they’d have a lot farther to travel for games, and likely have to pay higher prices. But it would be convenient for me, and the tickets would likely be at least a little less expensive and more obtainable for the A’s games than the Giants contests, if unlikely to be a bargain. And I could wear my Giants/A’s hat, a giveaway years ago at one of their interleague series.

Though odd, two teams in the same city (or at least metropolitan area) sharing the same stadium isn’t unprecedented. The Giants and Yankees shared New York’s Polo Grounds from 1913-1922; the Yanks played in the Mets’ (now-extinct) Shea Stadium in 1974 and 1975 while Yankee Stadium was being redone; the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns were both in Sportsman’s Park from 1920-53. The Braves (when they were in Boston) and Red Sox shared Fenway Park for part of 1914 and 1915. There may well be other instances of which I’m unaware.

As you’d expect, this has led to some unusual situations, even though games were scheduled, naturally, so that one of the teams was playing at home while the other was on the road. My favorite happened in 1944, when the St. Louis Browns, to the shock of everyone, won their only American League pennant. They were a legendarily inept team during most of their approximately half-century instance, but with World War II on, they had their window of opportunity to grab a flag, as many of the best major league players were in the military. In the National League, the St. Louis Cardinals won their third straight pennant, and suddenly the city would host the entire world series, all to be played in Sportsman’s Park.

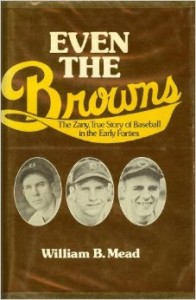

As William B. Mead’s 1978 book Even the Browns: The Zany, True Story of Baseball in the Early Forties reports:

The first clash between managers Luke Sewell [of the Browns] and Billy Southworth [of the Cardinals] was over a place to sleep. With housing short in wartime, the Sewells and Southworths had shared an apartment all season. The closet was for men, with Sewell’s clothes at one end and Southworth’s at the other. The Browns and Cardinals were never in St. Louis at the same time. As Sewell would be leaving with the Browns, Mrs. Sewell would entrain for the family home in Akron, and into the Lindell Towers apartment would come the Southworths.

However admirable this display of interleague cooperation might have appeared during the season, it would never do for the opposing managers to sit in the same living room after a World Series game, sipping bourbon and chatting politely with their wives. Besides, Sewell wanted to invite his mother, and Mrs. Southworth could hardly be expected to put up with a mother-in-law from the wrong family and, indeed, the wrong league. To the relief of both couples, another resident of the building was out of town in October and graciously let the Southworths use his apartment.

The Giants and Yankees ended up playing not just one but two World Series against each other in the same ballpark in 1921 and 1922, the final years they were sharing the Polo Grounds. Yankee Stadium opened in 1923, or else they would have staged the entire series there a third straight year, as both teams won pennants again. Babe Ruth likely would have hit even more home runs than he did if the Yanks had stayed in the Polo Grounds, though as it was he didn’t do too badly, totaling 714 homers in his career.

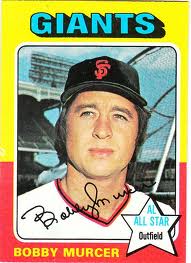

Neither the Yankees nor the Mets made the postseason when they were sharing Shea, though the Yanks came close in 1974. I was only twelve then, but the one issue I remember flaring up as a result of the co-tenancy was with star Yankees outfielder Bobby Murcer. The dimensions at Shea Stadium were different than Yankee Stadium, of course, and Murcer suddenly had a lot more trouble hitting balls in the seats. After averaging about 25 homers in 1969-73, his power plummeted, and he hit just ten—only two of them at Shea. As we would say now, the park probably “got into his head,” and I remember some national broadcasters making a big deal out of the power outage. Uncoincidentally, the following year he was traded to the Giants (now in San Francisco) for another superstar deemed to be underachieving, Bobby Bonds.

Bobby Murcer, thrilled to be out of Shea Stadium and playing in that other noted hitter’s paradise, San Francisco’s Candlestick Park.

As one of the most pitcher-friendly parks in the majors, AT&T will likely be as hard a place for Oakland hitters as the Coliseum—also one of the most pitcher-friendly parks in the majors, in large part due to its sizable foul territory. As to whether we’ll see them calling AT&T home for a while, that remains as indefinite a proposition as the A’s even staying in Oakland, their ballpark situation having dragged on for years with no resolution in sight.