Even after so many vaults from rock’s first quarter century have been cleared, I had no problem selecting nearly twenty reissues (sometimes featuring previously unreleased material) for a list that many critics would limit to ten choices. I by no means heard every obscure reissue, or every expensive box set. If I come across some of them next year, I’ll add them to the end of my 2018 list, as I have here for some noteworthy 2016 releases I didn’t hear until the past twelve months.

If there’s a trend in reissues, or at least the ones I like to hear, it’s the growing number of albums that are about as notable for their historical interest as their musical value—indeed, sometimes more notable for their historical interest. I feel there simply aren’t many acts left from this era I haven’t heard, or albums (released or otherwise) from this era I haven’t heard, that are going to blow me away. Is a record holding a high percentage of its merits in its historical significance such a bad thing, though? Not for those of us who care about how music’s made and its context, illuminating the corners of key performers and musical genres, as well as solving some mysteries about music that’s been around the block for decades.

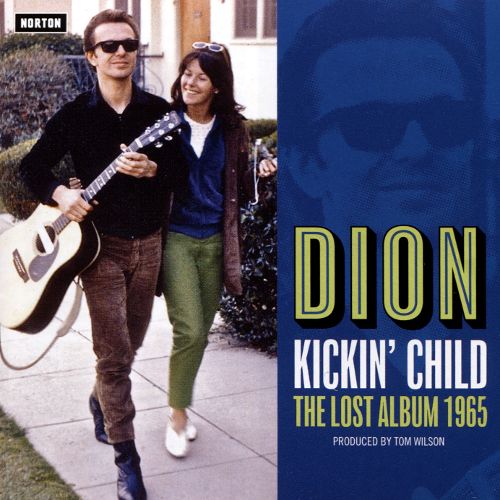

1. Dion, Kickin’ Child: The Lost Album 1965 (Norton). Although part of its subtitle reads “the lost album,” it should be clarified that this isn’t an unreleased album. Instead, it’s a compilation that simulates what a Dion folk-rock LP might have sounded like had these fifteen tracks been released on a full-length disc in 1965 (all having been recorded between spring and fall of that year). All of the material, as far as I can tell, has been previously available, even if you had to be a pretty dedicated Dion fan to hunt all of it down on various non-LP singles, the obscure Wonder Where I’m Bound LP, and the CD compilations Road I’m On and Bronx Blues. The tracks selected for this anthology are more, as Scott Kempner writes in his liner notes, “significant recordings comprising Dion’s ultimate folk-rock album [that] are presented now as they were originally intended…fifteen tracks that have been unavailable for decades.”

That out of the way, it’s still good to have the cream of his 1965 folk-rock-oriented recordings in one place, and not have to weave in and out of incongruous material that it was sandwiched between on previous compilations. It’s also a good way to appreciate Dion’s rather unappreciated, if uneven, contributions to early folk-rock, when he was among the first singers (and virtually the only veteran rock star) to immerse himself in the style fairly deeply. There are similarities to early Bob Dylan and (far more distantly) early Byrds in the backing, which has the tentative yet daring exploratory feel of some other artists following the Byrds and Dylan’s more confident leads (particularly as most of this was produced by Tom Wilson, who also oversaw Dylan and Simon & Garfunkel’s early folk-rock recordings).

Material-wise (and Dion wrote the majority of the songs here), he lacked the knockout punches of the leading folk-rockers, and some of these cuts are in truth more blues-rock than folk-rock. There are still some standouts, however, like his terrific adaptation of the obscure early Dylan song (unreleased by Dylan at the time) “Baby I’m in the Mood for You”; his cover of Tom Paxton’s “I Can’t Help But Wonder Where I’m Bound”; and his fairly successful if somewhat derivative ventures into gentle melodic folk-rock originals, like “Now,” “My Love,” and “So Much Younger.” (My story on Dion’s mid-1960s folk-rock phase, based on a recent lengthy interview with Dion himself, is in the November 2017 issue of the UK monthly magazine Record Collector.)

2. The Beatles, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band (six-disc deluxe version) (Apple/Universal). Where do you rank an album that, back in the year in was issued, would have topped many best-of lists, but has become so over-familiar that even a six-disc expanded version isn’t as exciting as it could be? If you’re me, you don’t worry too much about what number it takes on the list, but it doesn’t get #1, even in this deluxe box version. It’s a big move in the right direction in the packaging of the Beatles’ catalog, which until this 50th anniversary box had not taken the obvious step of expanding their classic albums in reissued formats. This one has the stereo and mono versions, plenty of outtakes, the classic cuts from the “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane” single (originally intended to be used on Sgt. Pepper), and the audio on Blu-ray/DVD discs if that rings your chimes. But the extras aren’t as exciting as they are on some other box set editions of classic vintage LPs, and the fans most interested in the bells and whistles probably already have a good deal of this in their collection, sometimes many times over.

That doesn’t mean I don’t care about Beatles material that hasn’t been available before. With The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, I wrote a whole book on that subject. But as I noted in that book, 1967 might have been the least interesting year of the Beatles’ career (if we focus on their core 1962-69 era) in terms of material that was unissued at the time. No longer touring, they were focusing on studio recording, and in making those recordings, building up tracks layer by layer. That means the different versions of songs they recorded for the LP—which form the bulk of the three dozen or so extra cuts on the box (counts vary according to whether you might consider a “2017 mix” previously unreleased)—aren’t all that different from the album versions we’ve heard all these years. Sometimes you essentially just get the backing track or elements of a track, which is interesting, but not so much that you’re likely to enjoy it over and over.

Whatever edition of Sgt. Pepper was issued (the 50th anniversary CDs also came in two-CD format with less bonus tracks), media coverage focused on the stereo remix by Giles Martin, George Martin’s son. I seem to be one of the critics least excited by ballyhoed remixes; it’s good, but it’s not that stupendously different from the original, and the original always sounded pretty good in the first place. The 1992 TV documentary The Making of Sgt. Pepper, featuring interviews with Paul McCartney, Ringo Starr, George Harrison, and George Martin (who brings up separate elements of some tracks at the mixing board) that’s also in the six-disc version is good, but long available on bootleg.

The 144-page hardback book might be the best reason to buy the box, as it hasn’t been available before and can’t be easily bootlegged, and is pretty well done, even if the details on some tracks (like the bonus ones on the mono CD) could have been better. And for all its size, the box is missing a few bootlegged or known-to-exist items—the avant-garde “Carnival of Light” outtake, John Lennon’s home demo of “Good Morning Good Morning,” and Lennon’s home recordings of “Strawberry Fields Forever”—that would have made the box more definitive, if more expensive.

You can probably tell I don’t feel like the $150 or so this box cost (prices vary according to where you buy it and the shipping, if that’s involved) quite justified the price tag. But don’t get me wrong – the quality even on the oft-circulated stuff is better than the bootlegs; a few of the previously uncirculated tracks (like the “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” where Lennon has a mechanical vocal, changing to a more rapid and natural phrasing at McCartney’s suggestion) are interesting, if not phenomenal; and the overall packaging is of a commendably high standard, even if there are a few questionable decisions and omissions. Hopefully there will also be a deluxe box for The White Album’s 50th anniversary, especially as there are much more, and much more interesting, extras to choose from (especially if you count the couple dozen or so demos they did at George Harrison’s home shortly before the sessions started). And then maybe they’ll finally go back to all of their albums to construct deluxe editions.

3. The Rolling Stones, On Air (Deluxe Edition) (Universal). More than most top rock bands of the era, the Rolling Stones have been tight-fisted about issuing rarities from their vaults, putting out little unreleased pre-1970 material. For that reason, this compilation of 1963-1965 BBC sessions can be welcomed as a major crack in the floodgates (though the super-deluxe box edition of their 1965 Charlie Is My Darling documentary did include an entire CD of previously unreleased material of the band in concert in March 1965). Although there’s a “standard” single-disc edition of On Air with eighteen tracks, the two-CD deluxe edition is much preferable, adding fourteen more songs.

As cautionary notes, there’s hardly any original material (though there are versions of the first two Jagger-Richard-penned hits, “The Last Time” and “Satisfaction”). At this point in their career, their repertoire was dominated by American blues/R&B/soul covers, and that’s what dominates this anthology (although it also has a rendition of Lennon-McCartney’s “I Wanna Be Your Man,” their second UK hit). Of course, they did such covers as well as anyone in the UK (or the world), and many of them are here to enjoy in versions different than the ones on their early records. The fidelity varies from tinny to excellent, but it’s always listenable.

There are also eight songs (all covers) that didn’t find a way onto official Stones releases, including a smoking “Roll Over Beethoven” that outdoes even the Beatles’ excellent version, as well as a superb “Memphis, Tennessee.” The other such tracks aren’t quite as good, but include the semi-blues-rap of Bo Diddley’s “Cops and Robbers,” as well as another Diddley number in “Crackin’ Up.” There are also performances of “Hi-Heel Sneakers,” “Fannie Mae,” and items from the catalogs of two of their biggest influences, Chuck Berry (“Beautiful Delilah”) and Jimmy Reed (“Ain’t That Lovin’ You, Baby”).

That wraps up the formidable positives, but here are the more critical observations. To bring up the Beatles comparisons that might be unfair but are inevitable, the Beatles were much more creative and adventurous in taking the opportunities with their BBC sessions to perform songs not available on their commercial releases. They did three dozen such numbers in all, albeit just one of which was an original composition. Although it’s known the Stones did a fair number of songs onstage in their early years that didn’t make it onto their records, as noted above, there are just eight here. It would have been great if they’d done more otherwise unavailable songs by their early idols Berry, Diddley, and Reed.

Of more importance, the Stones and their record label can’t change what they taped for the BBC, but they can be faulted for not making this compilation more comprehensive. There are fifty surviving 1963-65 BBC cuts that have been bootlegged, which means that eighteen are missing from this collection. Sure, some of them are additional versions of songs represented on the deluxe edition. But some are not on On Air at all, including nifty lesser-known tunes they recorded in the studio in their early years, like “Bye Bye Johnny,” “You Can Make It If You Try,” “Meet Me in the Bottom,” and “Don’t Lie to Me.” It’s even missing their BBC version of “Not Fade Away,” their first big British hit. Everything could have fit onto two CDs, as they have on past bootlegs. Had On Air included everything possible, it would have contended for a higher position on this list.

4. Laura Nyro, A Little Magic, A Little Kindness (Real Gone). Nyro’s career lasted, rather fitfully, almost thirty years. Her best two albums by some distance, however, were her first two, recorded when she was very young: More Than a New Discovery (1967) and Eli and the Thirteenth Confession (1968). They haven’t been too hard to get over the years, but this two-CD reissue is notable for featuring the rare mono versions of each one (in the US, Eli and the Thirteenth Confession was only issued in mono to DJs). Although there are only three bonus tracks, they’re significant: the 45 version of “Stoney End” (with different lyrics and vocal), the 45 version of “Save the Country” (re-recorded with a different arrangement for her third album), and, less essentially, the edited single mix of “Eli’s Comin’.” I wasn’t even aware there was a different version of “Stoney End” on 45 until this compilation, which also features lengthy historical liner notes.

Despite the high marks for the packaging, listening to these back to back doesn’t mask imperfections in the original works. The LPs were uneven, with a fair distance separating the most well known classics (“Wedding Bell Blues,” “Blowin’ Away,” “Eli’s Comin’,” “Sweet Blindness,” “Stoned Soul Picnic,” “When I Die”) and the more run of the mill tracks. The relatively average tunes, too, suffer from some similarity to each other, and the arrangements and production sometimes could have been a little gutsier and more imaginative. Yet as uneven as this is, it contains the bulk of her best material.

5. Gene Clark, The Lost Studio Sessions 1964-1982 (Sierra). This compilation is available in a few variations, the cheapest being a single CD, the most thorough being a package that also puts the songs from the CD on vinyl LPs; adds a couple CDs with extra tracks, even though these only add up to an EP’s worth of material; and a DVD with a mid-1980s Gene Clark interview. This review is for the most comprehensive edition, which with shipping will set you back almost $100, a high price considering a double CD could have fit all the music for those who aren’t fussy about deluxe goodies. This doesn’t stand up to Clark’s best solo material (let alone what he did with the mid-’60s Byrds), and like many such anthologies is more of historical interest than musical brilliance. But as Clark was an important figure as the primary songwriter in the original Byrds (and later a respected cult singer-songwriter and country-rocker), historical significance is a good enough reason to treat this as a notable release.

Of most note, at least to listeners like myself who view his Byrds work as his peak, are the seven 1964 solo acoustic demos (one previously released) that show him in uneasy transition between the troubadour folk era and the British Invasion. It’s as though he can’t quite decide whether to be a more mature version of the Kingston Trio or try his hand at more teen-oriented pop-rock, and the songs lack the grand melodies of even his early Preflyte songs with the Byrds, though there’s an affecting yearning naiveté. A couple rather ornate 1967 solo cuts (arranged by Leon Russell, with Hugh Masekala as a musical guest) are curiosities; “Back Street Mirror,” whether intentionally or not, sounds like a Bob Dylan satire.

Devotees of Clark’s solo work will focus on the early ‘70s tracks at the heart of the compilation, including eleven 1970-71 solo demos; a 1970 cut with the Flying Burrito Brothers; and four full-band country-rock-oriented efforts from 1972. Like much of Gene’s work, these (especially the solo endeavors) exude sincerity and contain some interesting wordplay, though I don’t find the melodies terribly memorable. Unfortunate but true: in common with many such archival releases, the later the recordings, the least interesting they are, as is the case here with five 1982 numbers. For all the work Clark did after the mid-1960s, I have to conclude he never found nearly as suitable a vehicle for the full arrangements of his songs as the Byrds — and never again wrote material as superb, as interesting as some of his solo stuff was in an idiosyncratic singer-songwriter way.

So on the whole this is for specialists, but at least for the high price you do get quality packaging, including thorough liner notes by Clark/Byrds biographers. The half-hour DVD interview done at Clark’s home in 1986 by Domenic Priore, incidentally, is pretty good, if basically filmed. Clark talks with intelligence and fair depth about various aspects of his career, including precise details about the writing of “Eight Miles High” (which he wrote for the most part, he explains). At times the visuals cut away from a straight shot of Gene talking to rare pictures (dominated by images from the mid-’60s), which add another element of interest.

6. Various Artists, Making Time: A Shel Talmy Production (Ace). American-born Shel Talmy was one of the most important producers of British ‘60s rock, most famous for the mid-’60s hits he worked on by the Kinks and the Who. At various times, he also produced David Bowie (in Bowie’s pre-fame mid-’60s days), the Pentangle, the Easybeats, Manfred Mann, the Creation, Chad & Jeremy, Roy Harper, Lee Hazlewood, and the Fortunes, as well as interesting flop discs by the likes of the First Gear, the Mickey Finn, and Ben Carruthers & the Deep. All of those artists and more are on this 25-track compilation, functioning as a basic overview of his range, although it doesn’t get deeply into any one act or include much in the way of rarities that comprehensive collectors won’t have elsewhere. If you are on the lookout for rarities, there’s a previously unissued alternate version of the Easybeats’ “Lisa”; Bowie’s “You’ve Got a Habit of Leaving” (released under the name Davy Jones) with a “previously unissued alternate overdub”; all-women rock group Goldie & the Gingerbreads’ “That’s Why I Love You,” with Genya Ravan; and Perpetual Langley’s girl group-ish “Surrender.” This might be a better comp for someone just getting into this era rather than the experienced collector likely to have a lot of it, but the extensive 28-page booklet of notes by compiler Alec Palao are a good bonus.

7. Jon-Mark, Sally Free and Easy (RPM). Jon-Mark is mostly known for his work as part of Mark-Almond, and his brief but significant time in John Mayall’s band in the late ‘60s (which included one of Mayall’s best albums, The Turning Point). Deep ‘60s collectors will also remember he was part of the semi-supergroup Sweet Thursday (also including Nicky Hopkins and future Cat Stevens guitarist Alun Davies), who made some of the most accurate and best quasi-Bob Dylan/Blonde on Blonde tracks, and played on some of Marianne Faithfull’s ‘60s recordings. Before most of this, he was also a solo artist in the mid-’60s, though he didn’t release much at the time. Sally Free and Easy is a notable gap-filling compilation, its 24 tracks including an unreleased Shel Talmy-produced LP he recorded for scheduled (but unfulfilled) release in autumn 1965, along with some outtakes and a 1965 single.

Fans of British folk guitar will detect similarities to Davy Graham in Jon-Mark’s dexterous eclecticism and, more distantly, Bert Jansch and Donovan in his skill on the instrument and vocals. He is, nonetheless, not as talented or exciting as any of those artists, whether as a guitarist, singer, or interpreter of folk songs. But it should be emphasized that big fans of the kind of music Graham, Jansch, and Donovan were doing then will like this. Occasionally, the approach is daringly innovative for 1965, whether it’s the use of sitar in “Sally Free & Easy” (also done by Faithfull and Pentangle in the ‘60s) or modest full band backing on the single “Baby I Got a Long Way to Go”/”Night Comes Down,” the latter song better known via the mod rock version by Mickey Finn. Also of interest is “If You’re Gonna Leave Me,” recorded in a much more orchestral pop-oriented version as “Bye Babe” four years later by Lee Hazlewood. Largely, however, the accent’s on his solo acoustic arrangements of folk standards. All of this was produced by Shel Talmy, and as with the Talmy compilation listed above, this CD features detailed liner notes by Alec Palao.

8. Various Artists, Great Guitars at Sun (Bear Family). There were great piano players at Sun (Jerry Lee Lewis and Charlie Rich), and good performers on several instruments, but guitars are what first come to mind when you think of the Sun sound. There were many more Sun recordings with fine guitar than can fit on a single-CD 28-song compilation. But this one does a good job, like its companion-disc-of-sorts Drums at Sun, at mixing tracks by legends (Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Roy Orbison) with important less famous names (Junior Parker, James Cotton, Rufus Thomas, Bill Justis, Little Milton, Earl Hooker, Billy Riley) and, at least to non-Sun aficionados, no-names (Dick Penner and Ernie Chaffin, among others). And while there are some familiar classics (“Mystery Train” by both Presley and Parker, Perkins’s “Matchbox,” Cash’s “Folsom Prison Blues,” Carl Mann’s “Mona Lisa”), most of the selections aren’t ones you’ll find on average Sun best-ofs. To mix things up a bit more, Roy Orbison’s “Ooby Dooby” and Billy Riley’s “Red Hot” are not represented by the versions on original Sun singles, but by alternate takes. Extensive track-by-track annotation enhances appreciation of this material, even if you’re pretty knowledgeable about Sun’s history.

9. Various Artists, Great Drums at Sun (Bear Family). Are drums the first thing you think of when you think of Sun Records? I thought so (meaning the answer’s “no”). Superb singers, yes; guitarists, definitely, whether great solo artists like Carl Perkins or noted session men like Roland Janes; and piano players, even if you can only name Jerry Lee Lewis and Charlie Rich. So this 28-track compilation feels a bit like an excuse to generate a novel anthology of interesting Sun material. On that level, however, it certainly succeeds, mixing material by icons like Perkins, Lewis, Rich, Elvis Presley, and Roy Orbison with names known primarily or exclusively to collectors, whether Billy Lee Riley or guys who make Riley seem familiar, like Jimmy Williams and Vernon Taylor. Give the compilers credit, however, for largely opting for off-the-beaten tracks by the bigger artists, and sometimes choosing alternate takes (including for two of the most famous songs here, Perkins’s “Boppin’ the Blues” and Rich’s “Lonely Weekends”) instead of the usual hit versions. It’s a good listen, even if I find it a peculiar concept, enhanced by excellent liner notes that focus on the drumming heard on these selections.

10. Van Morrison, The Authorized Bang Collection (Exile/Legacy). We’re back to primarily-more-of-historical-interest for this three-CD compilation of everything Van Morrison recorded for Bang Records in 1967, when he started a solo career after leaving Them. Except for the hit “Brown Eyed Girl,” I’m actually not that big a fan of this brief transitional era, when Morrison recorded in New York with producer Bert Berns. The material (which do include early versions of a couple Astral Weeks songs) isn’t that great, and while Morrison’s singing is good, the production (as he’s sometimes pointed out, and does again in the liner notes) wasn’t always sympathetic.

But if the actual music wasn’t among his very best, the archival packaging here is stellar. The seventeen songs on disc one have been issued in a lot of formats, but this CD uses original stereo and mono mixes. More interestingly, disc two (subtitled “Bang Sessions & Rarities”) has a bunch of previously issued alternate takes, as well as original mono single mixes for the completist. Disc three, the notorious “contractual obligation session” at which Morrison tossed off 31 ditties of less-than-serious song fragments as a kind of up-yours to help get out of his Bang contract, has been issued on previous CDs. Its authorized appearance here is a bit of a surprise given both its marginal quality (not fidelity, which is okay) and Morrison’s likely view of these performances as inessential to his core legacy. But they do make this compilation as complete as possible, though the 1967 date attached to them here seems puzzling, as previous Morrison literature has logically reported that they were cut in 1968 after Berns’s death, when Van was particularly eager to cut his association with Bang.

As another surprise, Morrison himself has the byline on the principal liner notes, which are fairly lengthy and quite interesting. As the notes bearing his credit for The Complete Them 1964-1967 a couple years ago were similarly fine, one wonders if Van might actually have it in him to generate a good memoir covering his entire career.

11. The Beach Boys, Sunshine Tomorrow (Capitol). Something like, but not exactly, an expanded version of Wild Honey, this two-CD compilation is a rather peculiar collection of Beach Boys recordings from mid-to-late 1967 (with one stray live track from 1970). Wild Honey itself is here in a new stereo mix, if that is important to you. The rest of disc one, however, is devoted to previously unreleased Wild Honey outtakes, alternate versions, backing tracks, and “session highlights,” as well a few November 1967 live recordings (along with a 1970 concert version of “Aren’t You Glad”). Disc two mixes Smiley Smile outtakes/alternates/backing tracks—not to be confused with material from the far more ambitious Smile, which preceded Smiley Smile—with more summer/fall 1967 live performances (or “live in the studio” recordings that the band considered overdubbing with crowd noise), as well as a 1967 version of “Surf’s Up.”

What you have here, then, is an extensive document of that half-year or so after Smile was abandoned that the Beach Boys worked together as a real band again, playing their own instruments, rather than supplementing Brian Wilson’s session-player-heavy productions. It would be a more definitive document, of course, if Smiley Smile itself was also included, but that couldn’t have fit onto two CDs. It’s a bit like getting a high-quality bootleg (complete with expert liner notes) of bits and pieces from various sources, many of the non-LP extras sounding incomplete or half-hearted.

If the intention is to argue that the Beach Boys remained at a creative peak after the collapse of Smile, I hate to rain on this beach, but I’m not sold. Aside from its best few songs (the mild hits “Wild Honey” and “Darlin’,” and maybe “Here Comes the Night” and “I Was Made to Love Her”), Wild Honey’s material doesn’t come within hailing distance of their best work during Brian Wilson’s prime.

Wild Honey has been around forever (even on CD), of course, so the main reason to dig into this is for the abundant stash of extras. But the studio outtakes, with some outstanding exceptions like “Can’t Wait Too Long” and “Time to Get Alone,” just don’t make for cuts you want to hear after you’ve absorbed their scholarly significance to how the Beach Boys were working in the studio. And the live tapes are, to be harsh, a bit of a damp squib, the band sounding generally thin and sometimes perfunctory, and at times (especially during the live-in-the-studio tapes) not even appearing to take the task too seriously. “Surf’s Up” is good, but that was really a Smile cut, not a post-Smile endeavor. As a ‘60s Beach Boys completist, I’m glad this is out there for purposes of historical research, but it’s really not too exciting on its purely musical merits.

12. Tim Buckley, Venice Mating Call (Manifesto). There have been quite a few live/outtake/demo Buckley releases in the CD era. Indeed, the amount of commercially available material Tim didn’t release during his too-short lifetime now exceeds the considerable running time on the nine studio LPs he put out before his death. The discography balloons quite a bit more with this two-disc set, taken from the same September 1969 gigs at the Troubadour in Los Angeles that yielded the 1994 CD Live at the Troubadour 1969. None of these performances duplicate tracks from the 1994 CD, although some of the songs are the same. Some of the tunes, however, don’t appear on Live at the Troubadour at all, among them such notable ones as “Buzzin’ Fly,” “Lorca,” and one (“(I Wanna) Testify”) that actually doesn’t appear on any other Buckley release.

As glad as Buckley fans (and I’m one) should be that this is available, it really is for Buckley fans only. Not because it’s deficient, but because Live at the Troubadour 1969 itself gives you a good idea of how he sounded in concert at this juncture in his career. Maybe it’s too harsh to label it more of the same, but it’s not too radically different. As a yet more contentious point, Live at the Troubadour 1969 was not Buckley at his most (or even relatively) accessible, Tim offering long, improv-leaning, jazz-folk workouts that were sometimes as much jams as songs, and not as melodic or craftily arranged as his best late-’60s studio recordings. It’s a little wearying to hear over the course of two CDs, especially if you’ve long digested the similar outings on Live at the Troubadour 1969. And guess what? If you want yet more, the single-disc Greetings from West Hollywood (also released in late 2017) has other previously unreleased recordings from the September 1969 Troubadour gigs, though two of the performances on Greetings from West Hollywood are also heard on the more highly recommended Venice Mating Call.

13. Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, Big Time Operator (Repertoire). Of the three most popular British acts of the mid-1960s to combine soul, rock, and jazz, Zoot Money was a fairly distant third (to Georgie Fame and Graham Bond) in significance. Even more than Bond, he’s barely known in the US—even Bond’s band is known by some as the place where Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce played together before Cream. And though his Big Roll Band was a very popular club act in the UK, they just managed one British hit, and that a fairly mild one (“Big Time Operator,” which made #25 in 1966). They were handicapped by a near-total reliance on covers of American R&B songs (albeit some of which were obscure even in the States), and Money’s raspy voice didn’t rival Britain’s top R&B singers. Even the presence of a young Andy Summers (then known as Andy Somers) on guitar wasn’t too notable, his work with the Big Roll Band being pretty low-key and jazzy.

Still, the Big Roll Band’s records—and there were a lot of them—were usually at least adequate, and sometimes more exciting than that, especially when Money’s organ and the horns got a chance to stretch out. This four-CD set can’t be faulted for thoroughness, including both of the Big Roll Band’s mid-’60s LPs (one studio and one live); a 1966 live set at the Flamingo in London; their nearly dozen non-LP singles; a couple tracks from a 1964 various-artists album; and four from Money’s 1968 Transition LP (presumably more weren’t included due to lack of space). All of these tracks have come out on previous CDs, though you’d have to be a pretty dedicated collector to already have all of them. But even if you do, there’s a significant bonus with eighteen previously unissued BBC tracks from 1964-67, which include some songs (all covers) not on their other releases.

Even on their few original songs, the Big Roll Band weren’t too memorable or groundbreaking. An exception is the obscure 1967 B-side “I Really Learnt How to Cry,” a Money-Summers original in which they finally move from fairly conventional R&B to something more melodically adventurous and personal, with an intricate classical-flavored guitar break. You also hear this on one of the Transition tracks, “Coffee Song” (more famous via its earlier, less subtle cover by Cream), though this was written by non-Big Rollers Tony Colton and Ray Smith. Money’s best track of the 1960s, the superb psychedelic early Pink Floyd-ish “Madman Running Through the Fields” (issued in 1967 during the brief time Money and Summers formed the band Dantalian’s Chariot), actually isn’t here—though fortunately it, its B-side, and other tracks Dantalian’s Chariot recorded for an unreleased album, were issued back in 1996 on the Chariot Rising CD. (A longer review of this album, along with my recent interview with Zoot Money, will appear in issue #47 of Ugly Things.)

14. The Beatles, The Christmas Records (Apple). The seven Christmas discs the Beatles made available only through their fan club from 1963-1969 have been bootlegged forever, and it’s unlikely many serious collectors of the group don’t already have these recordings in some format. It’s also true that while these seven-inch flexidiscs were amusing to some degree, they weren’t (unlike almost everything they released to the general public) brilliant art, mixing comic sketches with occasional not-so-serious musical ditties. And it can’t be denied that this seven-inch-sized box of all the singles is expensive, retailing for about $73 (not including shipping) online. Although it’s marketed as a “limited edition,” I can’t find any source that details how limited it is.

Now that I’ve dumped all the negatives in the lead paragraph, I can add that the packaging is very good, presenting each disc as a vinyl seven-inch single with the original artwork (which got quite florid from 1966 onward). The booklet has some brief historical liner notes, but also reproduces the fan club newsletters sent with the 1963-67 discs. And as I wrote in my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film, it’s striking how the material, “as much as any compilation of actual 1963–1969 Beatles tracks, reflects their changing characters, images, and even (to a limited degree) music and studio experimentation. Initially just a vehicle for a more-or-less standard Christmas greeting, even by the mid-’60s they were restlessly expanding beyond the limitations of their initial wholesome moptopness. Becoming increasingly less concerned with keeping up appearances, the ‘messages’ became more and more sardonically humorous, the ‘music,’ ‘sketches,’ special effects, and editing progressively odder, even avant-garde at times.” And now it’s commercially available to everyone, filling in a notable if minor gap in their official discography.

15. The Monks, Hamburg Recordings 1967 (Third Man). Getting deeper into primarily-of-historical-interest territory, this EP is of more value for the light it sheds on a cult act’s history than its actual contents. Not discovered until shortly before this release, these five previously unissued 1967 recordings were cut not long before the Monks—a group whose legend rests primarily on their furious minimalist pre-punk 1966 Black Monk LP—broke up. “I’m Watching You,” an outtake from the sessions from their final single, indicates there might have been a way for the Monks to maintain their eccentric ferocity while expanding their melodic boundaries, even if it sounds like a rather incongruous blend of pounding garage rocker and spacy, more psychedelic bridge. The other four tracks, cut at Hamburg’s Top Ten club later that year, are less promising attempts to meld the Monks’ trademark stiff rhythms with a poppier sensibility; the best of them, the moody “Yellow Grass,” is sadly unfinished, lacking vocals.

16. Various Artists, West Coast Nuggets: Transparent Days (Rhino). A double-LP vinyl release of thirty rarities from 1965-1968, mostly though not always from California, stretching all the way from Vancouver to San Diego. One side’s devoted to garage rock, one to folk-rock, one to psychedelia, and one to pop-rock. It’s doubtful that anyone but compiler Alec Palao has all of these in their original form, ranging as they do from the roaring Marin County garage rock of the Front Line’s “Got Love” to an unreleased 1966 demo of Beau Brummels guitarist/chief songwriter Ron Elliott doing “Candlestickmaker” (later reworked on the title track of his 1970 solo LP). Even the few relatively well known groups, like the Electric Prunes, Love, and the Music Machine, are usually represented by non-LP singles and rarities. Unlike other volumes in the various iterations of the Nuggets series stretching back to the Elektra double LP of the same name back in 1972, its scope is limited to acts from the Warner Brothers-controlled catalog. It’s not as knockout as the most celebrated Nuggets collections, but is extremely diverse and bound to have some items that even big collectors of the era and region haven’t heard.

17. Neil Young, Hitchhiker (Reprise). At the opposite end of the pole from the Monks, we have an album of previously unreleased material by a very famous artist, not a cult one, that also makes the list more for historical interest than the music it contains. Not that it’s bad—far from it. Recorded in a single night on August 11, 1976, this has solo acoustic versions of songs that would, for the most part, be re-recorded for 1977-1980 albums (though the title track wasn’t issued in an officially reworked version until 2010, and two songs, “Hawaii” and “Give Me Strength,” were previously unreleased). “Pocahantas,” “Powderfinger,” “Campaigner,” and “Human Highway” are among the most famous of these tunes; “Campaigner” is actually the same performance as the one on Decade, but has an extra verse that appeared on a German release and test pressing.

It’s always nice to hear Neil Young unplugged, as you can on archival releases and bootlegs of concerts going back to the mid-‘60s. I wouldn’t count these among his best compositions, however, and there’s a similarity to some of the melodies that tends to make the songs blend into each other. It’s a minor, pleasant addition to the huge Young canon, but not a significant statement as a standalone album. A more significant unreleased Young LP from the 1970s is the legendary Homegrown, recorded in late 1974 and early 1975, and almost released before Young decided to put out Tonight’s the Night instead. What is he waiting for?

18. Doctor Ross, Memphis Breakdown (ORG). Doctor Ross is one of those guys I’ve heard a few tracks from on various compilations, but I’ve never heard an entire collection of his work until this one. This anthology of fourteen sides recorded for Sun Records in the early to mid-1950s actually has the exact same recordings, in the same sequence, as a 1987 LP of the same title. There’s also a considerably more extensive compilation of his Sun work on Bear Family, on the 2013 CD Juke Box Boogie: The Sun Years Plus. For those reasons, this doesn’t get a higher position on this list. Nonetheless, it’s still brash early city blues—not full-tilt electric, but certainly far more urban than pre-‘50s country blues, with propulsive drive and some electric guitar, harmonica, and percussion. The most familiar song here is “Cat’s Squirrel,” covered by Cream on their first album, though they seem to have modeled their version on a more developed subsequent rendition Ross did for Fortune.

19. Various Artists, Woody Guthrie: The Tribute Concerts (Bear Family). Shortly after Woody Guthrie’s death from Huntington’s Disease on October 3, 1967, tribute concerts were organized at New York’s Carnegie Hall to benefit research into the illness. Both shows took place on January 20, 1968, and a similar benefit/tribute was staged at the Hollywood Bowl on September 12, 1970. Excerpts from both the New York and Hollywood concerts were released on a two-volume set in 1972, and now have been expanded into this three-CD box, which includes quite a bit of unreleased material. More than any other item on this list, this makes the cut more for its historical interest than its music, as this was more notable as an event than as a showcase for memorable performances.

The 1968 shows featured Judy Collins, Arlo Guthrie, Richie Havens, Odetta, Tom Paxton, and Pete Seeger. All of them did reasonable unplugged covers of various Woody songs, Paxton’s “Pastures of Plenty” perhaps coming off best, though none of these tracks were career highlights. The real reason these recordings are remembered is the surprise appearance of a superstar who hadn’t played onstage for more than a year and a half. Backed by the soon-to-be-Band (who’d soon record their debut LP), Bob Dylan delivered breezily confident versions of “I Ain’t Got No Home,” “Grand Coulee Dam,” and the most obscure of the three Guthrie tunes he covered, “Dear Mrs. Roosevelt.” While these are by no means among the best of his ‘60s rock tracks, in this context they’re clear highlights, fairly rocking the house in the midst of this otherwise rather sedate presentation (linked by stilted onstage narration from actors Robert Ryan and Will Geer). These cuts are actually more polished and focused than most of The Basement Tapes, and one wonders what kind of concert Dylan and the Band could have done at this time focusing on original material, though this would not come to pass.

Some of the same acts (Arlo Guthrie, Seeger, Havens, and Odetta) were also part of the Hollywood Bowl bill, joined by Country McDonald, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Joan Baez. Again, these performances (Baez’s “Hobo’s Lullaby” being a standout) are neither disappointing nor electrifying—although this time around, more had full-band arrangements (the backup musicians including Ry Cooder and sometime Flying Burrito Brothers Chris Ethridge and Gib Guilbeau). Again there’s narration (by Geer and Peter Fonda) that, while important to preserve as a document of the event, dampens the momentum of the listening experience.

As usual, Bear Family goes the extra mile and then some in the packaging. The label dug up around a couple dozen unissued tracks, though none of them are by Dylan, and most are from the Hollywood Bowl performances (tapes couldn’t be located for some other songs known to have been played). There’s also a 160-page hardback book of liner notes, and a hardback 85-page replica of The TRO Woody Guthrie Concert Book, a songbook-with-photos companion to the concerts that was originally issued in 1972. As with some other Bear Family boxes, the book of liners is in some ways more interesting than the CDs, with detailed memories from the participants; vintage photos from the shows; and reprints of programs, tickets, newspaper reviews, posters, and original manuscripts of Woody Guthrie lyrics. Bonus tracks on the third CD include interview excerpts with some of the performers about the concerts, and the long-winded seven-minute poem Dylan recited at his April 12, 1963 concert at New York’s Town Hall, “Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie” (though that was previously released on his 1991 box The Bootleg Series Vol. 1-3). (My fuller review of this box will appear in issue #47 of Ugly Things.)

The following four records came out in 2016, but are worth a mention, as I didn’t hear them in time to put them on my 2016 list.

1. Fela Ransome Kuti and His Koola Lobitos, Highlife-Jazz and Afro-Soul 1963-1969 (Knitting Factory, 2016). This observation isn’t going to fly well with some Fela fans, but his Afrobeat recordings — and I’ve heard about a dozen albums of them, spanning the late 1960s to the early 1980s — aren’t the most varied musical endeavors. Often it seems as though you can chart the peaks and buildups of his lengthy tracks as though they were following similar graphs. If you prefer more heterogeneity in your sounds, you might prefer, as I do, this three-CD set of his earlier work. Taken from singles, his first studio album, the slightly lo-fi concert LP Afro Beat Live, and other recordings, it in some ways finds him evolving toward the Afrobeat style. But it also, as its title indicates, has a fair amount of soul, jazz, and highlife, sometimes instrumental, sometimes with English lyrics. The songs are usually in the three-to-five-minute range instead of groove-oriented workouts, and they’re fairly diverse, with some great weird slightly dissonant (or are they actually slightly out of tune?) horn lines. They’re also fairly different from the non-African soul and jazz he was clearly influenced by, mixing in a lot of African influences and his own originality. There’s plenty of uplifting energy throughout this extensive compilation, which has value far exceeding its historical documentation of Fela’s pre-Afrobeat roots.

2. Bob Dylan, The 1966 Live Recordings (Columbia/Legacy, 2016). Even if I’d obtained this 36-CD box set before 2016 ended (I admit I didn’t), it’s doubtful I could have listened to the whole thing before I compiled my best-of list for that year, as it was issued November 11. Even some people I know who bought it upon release haven’t gotten through everything. I have, and you don’t have to hear it to know that, even if you’re a Dylan fan, you have to be extremely committed to hear the entire production. Including much or the entirety of many shows from his 1966 tour, the set list rarely varies. So you hear well over a dozen of these concerts in part or full, usually in excellent sound, though a few lo-fi audience recordings are placed on the final discs.

Especially since one of the best of these shows came out in 1998 as The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The “Royal Albert Hall” Concert (though it was actually recorded in Manchester), this is really more of an extensive historical document than a pleasure cruise. Of course, this was about the most historic rock tour ever, with Dylan encountering some controversy and occasional audience hostility for playing loud rock music with future members of the Band, even though he split his sets into acoustic and electric halves. If you’ve heard the Manchester set over and over (as many have, since it was bootlegged for decades before its official release), the primary interest lies not in the music, which is rather similar (if passionately delivered) from date to date. It’s in the audience reaction, which isn’t as negative as has often been reported, with a clear majority applauding the electric rock numbers.

However, the objections of the small minority of hecklers are very vocal and nasty, especially in his UK concerts. That leads to some strange, at times impenetrably indistinct stoned-sounding spoken introductions and comments from Dylan. One of his between-song ramblings at his final London concert goes on for several minutes, and Dylan’s not noted for such extensive on-stage banter. For those who do want to focus on the music, it’s good, though one wishes his electric version of “Positively 4th Street” was taped more than once in good fidelity (as it was for the first concert preserved here, in Sydney on April 13, 1966). Other than that, the main variation in the electric sets is in the tempos and some vocal nuances, though he and the soon-to-be-band (then still the Hawks) clearly settle in and get more comfortable the more the tour progresses. If you want detailed analysis of the tour and the recordings, Dylan scholar Clinton Heylin supplies it with his 2016 book Judas!: From Forest Hills to the Free Trade Hall: A Historical Overview of the Big Boo.

3. The Zombies, The BBC Radio Sessions (Varese Vintage, 2016). Is this double CD good value if you’re the kind of Zombies fan who wants to have everything they did? No; there are just seven unreleased tracks, one of which is an interview, another of which is a third version of “Tell Her No.” Is it still a good listen, especially judged against a rather shallow pool of reissues of specific interest to me? Sure, and it’s enhanced by good thorough notes by Andrew Sandoval. The Zombies’ greatest strength was their moody, often minor-keyed original material, so in a sense it’s a shame that the majority of this features covers of American R&B/soul material, at which they weren’t as skilled interpreters as, say, the Beatles or Rolling Stones. On the other hand, many of these covers didn’t make it onto Zombies studio releases, so this gives you the chance to hear otherwise unavailable songs. Although a few of the bluesiest items are awkward, generally these cuts are pretty good, the clear highlight being their almost eerie reading of “The Look of Love.” As is par for most BBC sessions, the performances of the originals aren’t as strong as the studio versions, but there are some good ones here, including some neglected flop singles and B-sides like “Just Out of Reach,” “I Must Move,” and “Whenever You’re Ready.”

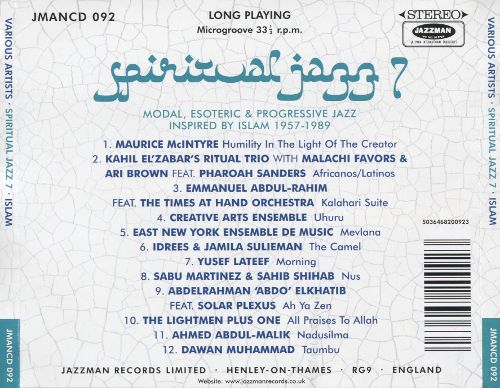

4. Various Artists, Spiritual Jazz 7 (Jazzman, 2016). Sometimes a reissue’s interesting, or certainly offbeat, enough to merit a place on lists like these even if it’s in a genre that’s not my main passion. Qualifying on those grounds is Spiritual Jazz 7, subtitled “modal, esoteric & progressive jazz inspired by Islam 1957-1989.” (There seems to be a typo there, as one of the track’s from 1999.) There are a few prominent names here (most notably Yusef Lateef and Pharoah Sanders), but few of them are too familiar, and probably some of them aren’t likely to have been heard even by listeners with big jazz collections. The Islam content isn’t too overt, even on the tracks with vocals; the spiritual inspiration, whether for these specific cuts or for the musicians’ lives and art in general, is spelled out more explicitly in the extensive liner notes. The religious dimension aside, it’s a varied collection of progressive jazz over a period of a half century, more than half of it hailing from the 1960s and 1970s. Some of the material’s damned obscure, and/or from damned obscure small labels, one (the Lightmen’s “All Praises to Allah (Pts. I & II)”) even sourced from a seven-inch single on the drummer’s Lightin’ imprint.