It was a good year for rock history videos, at least as measured by how many were worth watching. If you don’t have cable, you’ll probably miss out on some that don’t get into theatrical or DVD/Blu-ray distribution. I don’t have cable, and have to scramble to catch some when I’m house-sitting up the road. So I didn’t get to see everything, just like I didn’t get to read or hear everything. Yes, I know the Linda Ronstadt documentary, for instance, isn’t here. I haven’t seen it, though I probably will eventually when it comes out on DVD/Blu-Ray.

Most of these dozen or so films got far less distribution than the Ronstadt doc, and some of them were barely seen at all. My #1 choice might surprise some readers, since it focuses on an era later than my usual specialty.

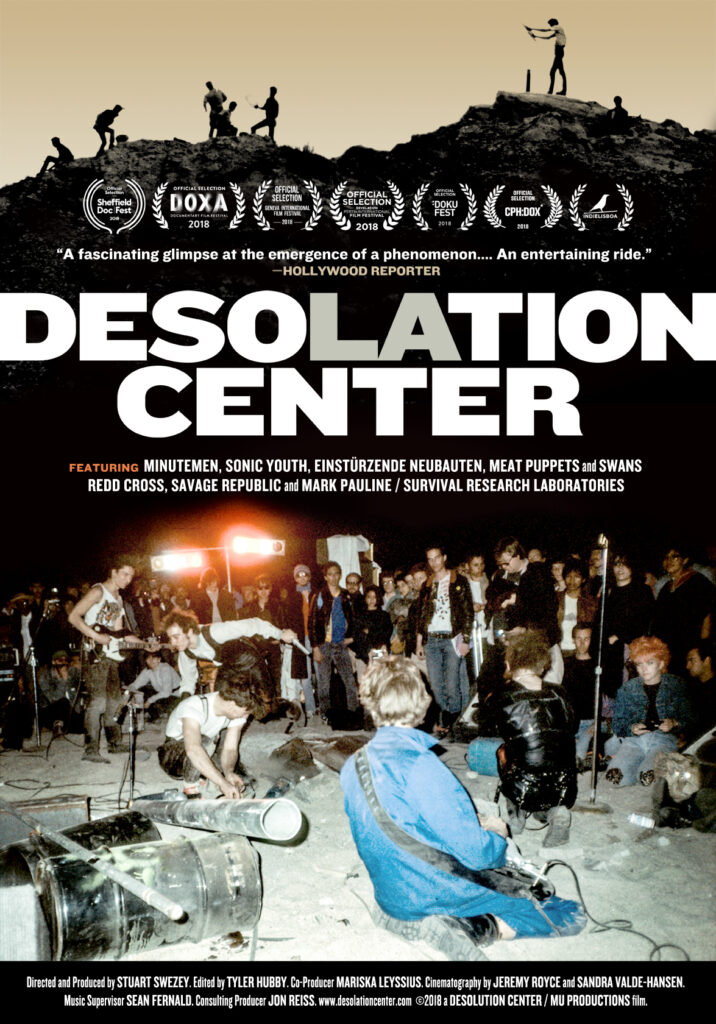

1. Desolation Center. Between 1983 and 1985, Stuart Swezey promoted exotic underground punk/avant-rock rock and industrial music shows in the Southern California desert near Los Angeles. He was also behind an equally unlikely “Joy at Sea” one aboard a boat in the San Pedro harbor, featuring the Meat Puppets and the Minutemen. Taking place under the Desolation Center banner, these are documented with more detail than anyone thought possible in the new film of the same name. Directed by Swezey himself, it’s built around an abundance of shaky vintage lo-fi film clips and audio, as well as recent interviews with many of the musicians and participants (including Swezey). Almost all of the surviving notable performers contribute recollections, including not only some Minutemen and Meat Puppets, but also key members of Sonic Youth (though not Kim Gordon), Einsturzende Neubauten, Savage Republic, Redd Kross, Perry Farrell (then part of his pre-Jane’s Addiction group Psi-Com), and industrial/performance art group Survival Research Laboratories.

Even if you’re not into that kind of underground rock, you might well find the film fascinating. Now well into middle age and veterans of hundreds if not thousands of shows, the musicians (and indeed the numerous audience members and organizers who also have screen time) often still speak of these happenings with a sense of awe. The archive footage and photos capture the odd settings to which fans were bused to (in actual school buses) from L.A., at points beyond which paved roads ended. Both musicians and audiences were free to mingle and experiment in ways not possible in conventional indoor venues, sometimes using explosive pyrotechnics. In retrospect, as some of them acknowledge, that could have been dangerous, as when a metal plate in one of Survival Research Laboratories’ exercises went flying over the audience.

Usefully, the first part of the film also explores how difficult it was to stage punk shows in Los Angeles in the early ‘80s due to police harassment, leading in part to taking the music to a place beyond their reach. They couldn’t escape the authorities altogether, the Bureau of Land Management sending Swezey a letter in 1985 that helped him decide to discontinue the events. The musicians and others at the Desolation Center shows discuss them with humor and insight, also noting their influence on subsequent far bigger desert spectacles like Coachella and Burning Man. The Desolation Center concerts, however, had a sense of spontaneity and edginess missing from those far bigger enterprises, and that comes across vividly in this well-made documentary. I interviewed Swezey about the film here.

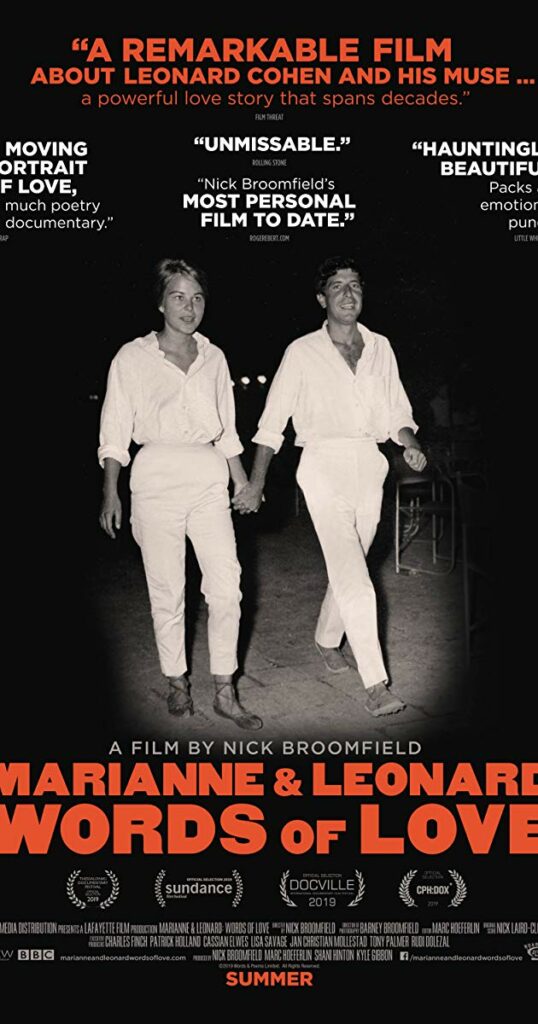

2. Leonard Cohen, Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love. Two notes first that are not words of caution, but of clarification. Although the title leads you to believe this is centered around Leonard Cohen’s lengthy relationship with Marianne Ihlen, and much of the film does dwell on that, it’s about as much of a Leonard Cohen documentary as a movie about the couple. And while it was directed by Nick Broomfield, known as a sort of guerilla documentary filmmaker who corners people who don’t want to talk on screen about controversial subjects, this is a pretty straightforward movie that doesn’t use that approach. It combines plenty of vintage footage (much taken from home/amateur movies, especially the scenes with Ihlen), Cohen concert snippets from throughout his career (none too extensive), and interviews done for the film with figures who knew Cohen or Ihlen.

Just because it’s not quite what you might expect doesn’t mean this isn’t worthwhile, whether taken as a Cohen documentary or one on him and Ihlen. There might not be a whole lot here you don’t know if you’ve read the best Cohen biography (Sylvie Simmons’s I’m Your Man), but it’s a well done overview that ties together the major points in his evolution. Although the interviews aren’t that numerous, some key associates weigh in with interesting observations, including Judy Collins, producer John Simon, less expected participants like folk singer Julie Felix, and Cohen guitarist Ron Cornelius, who actually has the most lively comments. Some relatively unfamiliar territory is covered, like Cohen’s concerts, apparently fairly numerous, at mental institutions. Also discussed are the difficulties faced by children who grew up in the permissive bohemian environment of the Greek island Hydra (where Cohen and Ihlen spent much time), who as adults succumbed to alcoholism, suicide, and in the case of Ihlen’s son (not with Cohen) Axel, mental illness.

Most moving of all is the observation by one Cohen associate that of the many women who were involved with (and often threw themselves at) Cohen, Ihlen was the only one who wasn’t star-struck. Although their relationship was not destined to stay the course, Cohen did send her a tender message when she was virtually on her deathbed – and the scene of her hearing that message is actually in the film.

3. Barbara Rubin, Barbara Rubin and the Exploding New York Underground. Filmmaker Barbara Rubin’s relationship to rock music was tangential, if notable. She was the person who alerted Andy Warhol and the Factory to the Velvet Underground at the end of 1965; maybe they would have gotten together anyway, but that doesn’t mean her connection wasn’t prescient and important. She was also a friend of Bob Dylan (whom she also connected with Warhol, if briefly), and appears with him in a picture on the back cover of Bringing It All Back Home. But she’s primarily known as an experimental filmmaker, although her career in that field was brief, and most noted (and notorious) for her half-hour 1963 movie Christmas on Earth, which was rawly sexual and radical for its time, and perhaps still is today.

Since this documentary aptly focuses much more on her movie-making, and her substantial influence on underground scenemakers like Warhol and Allen Ginsberg, than her role in rock music, it could be questioned why it’s on this list. Well, it’s far more interesting, and much better done as a film, than some documentaries on much more famous actual rock musicians on this list. Even if Jeff Beck and John Lennon might have had more interesting lives, the docs on them reviewed near the bottom of this list aren’t that great. This one deftly weaves a great deal of footage from Rubin’s movies, home/amateur movies, films by Warhol and others, and recent interviews with those who knew her for a fast-moving portrait of a pretty uninhibited character whose volatile life took some wildly unpredictable turns. It’s pretty amusing, as a rock snob aside, to see Kinks spelled “Kings” on a list of celebrities she hoped to feature in a film that didn’t get made.

After her film career sputtered, her late-‘60s rural retreat with Ginsberg and some other friends didn’t end well, culminating with a wholly unexpected shift to Orthodox Judaism. Although the director didn’t corral really famous people into his interview list (with the possible exception of avant-garde filmmaker/critic Jonas Mekas, who worked with Rubin quite closely), relatives, friends, and colleagues speak pretty eloquently about her inspirational and frustrating character. There’s some footage of the VU and Dylan (not much if any exclusive to this documentary), and a few stories about their interactions with Rubin, for those who especially want to zero in on the rock content.

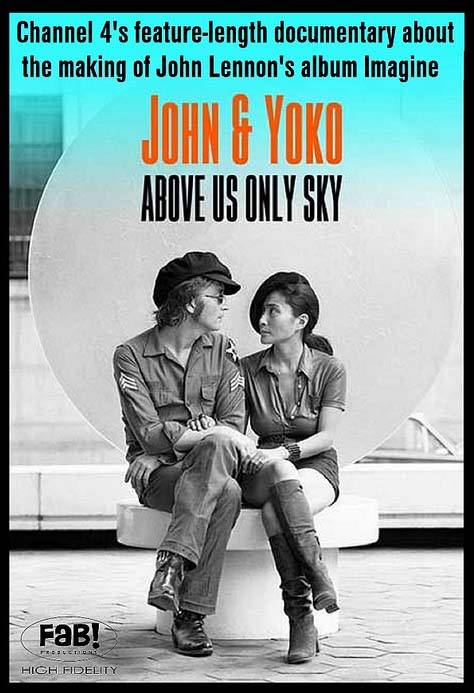

4. John Lennon & Yoko Ono, Above Us Only Sky. Technically this bears a 2018 date, but it doesn’t seem to have been shown on TV until 2019, and didn’t come on DVD until later in the year. Although it’s centered around the making of the Imagine album, there’s a fair amount about their lives in the late 1960s and early 1970s. There’s nothing quirky or unexpected about the documentary’s approach, which is fine. Besides plenty of period footage of Lennon and Ono at the Imagine sessions and in the Tittenhurst estate in which they were then living, there are recent interviews with a host of people who were around them at the time. Among them are Imagine musicians Klaus Voormann, Jim Keltner, and Alan White, as well as less well known personal assistants, engineers, photographers, music bizzers, and journalists who were on the scene. There’s only a bit of recent interview footage with Yoko herself, but more of John’s son Julian. Unlike some of the numerous Lennon docs, this doesn’t over-idealize his life, though the portrait is gentle and positive. It sticks mostly to actually covering what happened, which more music documentaries should do.

The DVD has a few modest but noteworthy extras, particularly color footage of John and Yoko busking through “Oh Yoko!” on May 24, 1969 at their brief stopover in the Bahamas before continuing to Montreal to stage their Bed-In for peace. There’s a fuller version of the strange, halting conversation between John and Curt Claudio, a creepy American fan who managed to get into Tittenhurst; Lennon shows a good deal of consideration and rational humility considering the intrusion. There’s also split-screen footage of John working on “How Do You Sleep?” and “Oh My Love.”

5. Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation (PBS). Does a TV program count as a film or video? Well, this did play a few festivals and theaters, including one in Berkeley where a few people involved in the film had a Q&A. So yes, this movie-length work, a part of PBS’s American Experience series, makes the cut on technical grounds. More notably, it’s worth watching as a decent survey of Woodstock as a social/cultural event, with vintage and fresh voiceover interviews with many of the event’s promoters, producers, performers, and attendees. Note that those wanting a focus on the festival’s music might be disappointed; it isn’t entirely neglected, but there are only bits of actual performances, commentary running over some of that footage. That’s okay, though, considering how much footage is in the actual Woodstock film (both the original and expanded versions), and how much more circulates unofficially. This is more the story of the event’s genesis, and how the festival was experienced, musically and otherwise, by the huge audience.

Besides the extensive voiceovers (no talking heads here), there’s quite a bit of previously unreleased footage of stage construction, and audience reaction/swimming/free food feeding, taken (according to the Q&A) from 35 hours of Woodstock movie material made available to the filmmakers. The most amazing facet of the festival is how it happened at all, considering how many logistical problems it encountered, and how hopelessly behind schedule things were even before it started. At one point, one of the organizers remembers being told that for everything to be built according to plan, they’d have to wait until November. Audience memories of the communal vibe that arose on the grounds and the weekend’s significance to their lives are poignant while, for the most part, avoiding undue sentimentality. And just as it became a free festival, you could watch this on PBS for free – something you can’t say of the 38-CD fiftieth anniversary Woodstock, which lists for $799.98.

A couple music nerd notes: the previously unseen footage includes snippets of performances by some of the most obscure artists at Woodstock – indeed, so obscure that most people don’t know they were there. Among them are Sweetwater, Quill, and Keef Hartley. Also, while David Crosby refers in a voiceover to CSNY’s set as being their first live appearance, it was in fact their second; they’d done their first concert just a couple days before, on August 16, in Chicago. In fact, on the original chart-topping Woodstock album, Stephen Stills himself refers to it as “the second time we’ve ever played in front of people.” It’s not as egregious a myth as the oft-repeated assertion that the Rolling Stones were playing “Sympathy for the Devil” when someone in the audience was killed at Altamont (they were actually playing “Under the Thumb”). But it’s an urban legend whose momentum will only gather steam after this broadcast, and needs to be halted before it gets out of hand.

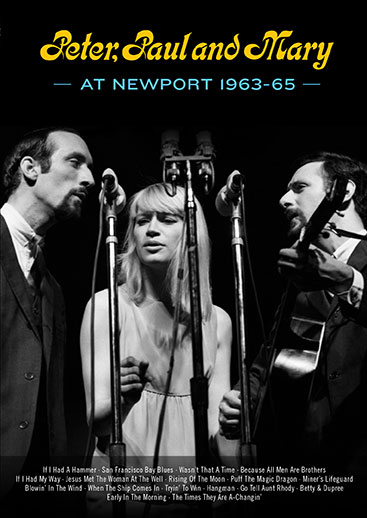

6. Peter, Paul & Mary, At Newport 1963-65 (Shout Factory). Peter, Paul & Mary’s energetic, downright swinging performance of “If I Had a Hammer” was a highlight of Murray Lerner’s Festival documentary, which featured footage from the mid-‘60s Newport Folk Festivals. So it’s a delight to have about an hour of clips of the trio at the event on this DVD, which leads off with the same version of “If I Had a Hammer” seen in Festival. PPM’s biggest hits are here (“Hammer,” “Blowin’ in the Wind,” and an odd Peter Yarrow solo rendering of “Puff, The Magic Dragon”), but so are some of their better “deep” LP tracks, like “If I Had My Way,” their covers of Bob Dylan’s “When the Ship Comes In” and the Weavers’ “Wasn’t That a Time,” “The Rising of the Moon,” and “Hangman.” The less impressive songs tend to be the ones that are shown only in partial performances. The filming is basic but effective, the best jobs being done with the clips that focus on the trio at an apparent nighttime spot, huddled closely around the mikes. Yarrow and Noel Stookey added a bit of commentary on the soundtrack, but these are brief bits that don’t unduly intrude on the music.

It’s true that they weren’t nearly as good at blues or comedy as straightahead earnest folk, brought home by their covers of “San Francisco Bay Blues” and “Betty & Dupree,” and an excruciating semi-parody (featuring just Yarrow and Joan Baez) of the tiresome folk tune “Go Tell Aunt Rhody.” If you want more niggling complaints, there certainly could have been more in the way of annotation. The different years of the performances aren’t even identified, though Yarrow contributes some succinct liner notes. But overall it’s a valuable document of Peter, Paul & Mary at the peak of their fame and powers, at the festival that meant more to them and the folk community than any other.

7. David Crosby, Remember My Name. David Crosby’s had an interesting life, both musically (primarily as part of the Byrds and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young) and personally (with well-documented drug and health problems, romances, and feuds). This documentary doesn’t cover a whole lot that you can’t find out in numerous books, some very good, about the Byrds and CSNY, along with his own middling memoir. It does have numerous archive snippets of live performance and interviews, and some fresh interviews done with past and present associates. But its main value lies in the extensive interviews done specifically for the film with Crosby himself (by veteran rock journalist/director Cameron Crowe, although Crowe didn’t direct this movie). He talks with more candor than the usual documentary subject about, on the negative side, the women he’s hurt, his overindulgence in drugs, and the trail of musicians in the Byrds and CSNY with whom he’s no longer on speaking terms. He is less evasive than most stars (or former stars, if you want to be cruel) in the line of questioning, readily admitting to his failures without much in the way of excuses or self-pity.

While it’s okay, and maybe more than okay given the fair entertainment value in listening to Crosby tell stories in his own words, there certainly could have been more, or more specifically about his music. If you’re looking for insights into his contributions to “Eight Miles High,” or how exactly songs were chosen out of a large pool for CSN’s debut (or CSNY’s Deja Vu), you won’t find them. General observations about the Byrds and CSNY’s contributions (incidentally, he views CSN and CSNY as entirely different ensembles) are fairly on-target, but not surprising to those who know their folk-rock history. Occasional comments stand out, like his admission that he didn’t go a great job producing Joni Mitchell’s first album, though he feels he did capture her essence. More embarrassingly (though it seems Crosby’s beyond embarrassment at this point), he remembers Mitchell taking the floor at a private party to debut a song obviously directed, negatively, at him – and playing it twice.

Some of the interviews with Crosby intimates are frustratingly meager. Certainly I would have liked more than a few words from the Byrds’ Chris Hillman, perhaps at the expense of photographer Henry Diltz’s blathering about the significance of Croz’s astrological signs, which even Crosby finds overbearing. There’s also a lack of specifics as to exactly why no one else in CSNY (including longtime best friend Graham Nash) will talk to Crosby now, either from Crosby or the other three. There’s the sense those relationships fell apart not only through actual dislike, but just from the burnt-out stress of their off-on supergroup dynamics over the course of nearly half a century. And in keeping with so many documentaries, there are almost obligatory insertions of less interesting sequences of him performing his recent music, and discussing how much family and home now mean to him, though these are kept shorter than they are in many comparable productions.

8. Bill Wyman, The Quiet One. A documentary about Bill Wyman works with a big advantage and a big drawback. The big advantage is that Wyman kept a thorough, almost obsessive-compulsive archive of his career. The big drawback is that, although serious fans of the Rolling Stones appreciate his contributions, he was the least interesting member of the group in the three decades or so he was their bassist. So this film does have a lot of cool vintage photos that haven’t often or ever been seen, as well as numerous snippets of rare or home movies (though nothing on the order of, say, an exciting performance of a full song). These are more interesting the earlier in the career they’re from, going back to his pre-Stones days in the Cliftons.

The drawback? Although Wyman provides fairly extensive comments and there are a few voiceover comments from other Stones and associates (though not Mick Jagger or Keith Richards), many aspects of his and the Stones’ music are not discussed. Wyman was an important contributor to the development of “Jumping Jack Flash” and “Paint It Black,” but this is not mentioned, which is a flaw, not a mere oversight; even if he didn’t want to get into the thorny issue of why he didn’t get songwriting credits, the stories themselves would have been interesting enough. There’s nothing about his songwriting for the group, which though meager was interesting (especially “In Another Land”), or how he felt about Jagger-Richards’ near-total domination of the band’s composing. For that matter, there’s nothing about how he worked with his bandmates in the studio, let alone how he felt about Keith Richards playing the bass parts on some of the records.

I suppose there are some general moviegoers and critics who’d complain that getting into such details would bore the audience, who’d prefer what the movie does discuss about his difficult romantic life, especially his controversial second marriage to a woman who was underage when they started dating. But such a documentary by definition has its strongest appeal to big Rolling Stones fans, who would appreciate hearing more about the music, and maybe about some aspects of the music and Wyman’s role that haven’t come to light. The movie doesn’t get as deeply into the more controversial aspects (and, for that matter, interesting non-controversial aspects) of his personal life and the Stones as his books Stone Alone and Rolling with the Stones do. Those books are out there for those who want a fuller story, but there’s no reason this movie couldn’t have been a fuller portrait as well.

9. The Harder They Come: Collector’s Edition (Shout Factory). Certainly this would have ranked higher, and near the top, if this marked the first time this legendary early-‘70s Jamaica-set film was reissued. It doesn’t, so it’s primarily judged here for its extras, which are both bountiful and uneven. The main bonus is director Perry Henzell’s follow-up movie No Place Like Home, which though mostly filmed shortly afterward was not finished until 2006. Compared to The Harder They Come, it’s a letdown, though it too is set in Jamaica. Reggae music isn’t a significant factor this time around, but more crucially, it has a half-baked feel, whether due to its troubled production or not. Tracking the brief affair of a visiting American helping with a TV commercial shoot and an ambitious young Jamaican on the set, it blurs a slender plot with cinema verité-ish glimpses of various facets of island life. There are some interesting scenes and certainly some gorgeous scenery, with much intense hi-tech restoration necessary once the footage was found. But it seems more like a sketch than a fully realized project, though there are insights into culture clash here and there.

That’s just part of one disc of this three-disc set, which also has the original The Harder They Come, a cult classic for its reggae soundtrack, star singer Jimmy Cliff’s performance in the title role, and its gritty portrayal of Kingston ghetto life. There are hours of extras, but the commentary by reggae expert David Katz is disappointing, sounding as if he’s reading from an essay instead of directly commenting on the action. In that case, it should have been used as liner notes, and a film expert or surviving person involved in the production used as commentator. There are a bunch of short documentaries and interviews (including with the late Henzell) related to the making of both The Harder They Come and No Place Like Home that range from quite interesting—the one with Harder photography director David MacDonald is the best—to associates who ramble too long. The ones tied to No Place Like Home do reveal what a struggle it was to complete the movie decades later, with much detective work involved in finding surviving footage and restoring it to much more watchable condition.

A third disc includes more bonus features on Dynamic Sound Studios, the restoration of No Place Like Home, anatomy of some scenes, Henzell’s home and production center, and Henzell’s disciples. The disc would not (unlike the other two discs) play in my Blu-ray player, and I’ll add comments on it when I’m able to view it in proper operation.

10. Bob Dylan, Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story (Netflix). Although Dylan’s mid-‘70s Rolling Thunder tours don’t seem like the most controversial subject, this documentary caused its share of controversy, mostly because some of the interviews are with fictional characters (and the one with Sharon Stone is about fictional incidents). But the bulk of this two-hour, twenty-minute film uses actual footage from the tours, mostly focusing on performances by Dylan. Those scenes are the highlight of this for-the-most-part documentary, as his renditions (mostly of mid-‘70s material, with a few pre-Blood on the Tracks classics as well) are intense, sometimes to the point of being weird. Dylan was interviewed by filmmaker Martin Scorsese, but doesn’t say much of consequence, admitting he doesn’t remember much. A few other real participants in the tours get some talking head time too (like Joan Baez, Roger McGuinn, Scarlett Rivera, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Ronee Blakley), but it’s not the most straightforward or thorough account of what took place.

Opinions about this doc were strong, both from viewers ecstatic over its contents, and those who felt the fictional segments diminished its merit. I’m not passionate enough about the subject matter to take a vehement position. If fictional stuff was thrown into a documentary on an act or period that meant more to me, I might be up in arms. It doesn’t bother me here; in fact, from a cinematic perspective, these are some of the more entertaining parts. They’re also pretty convincing, since the actors – uncommonly for tricks like this – underplay their roles, instead of giving away the game with obviously outrageous statements or exaggerated behavior. As a history of the tours, this would have been more valuable had it included more material on the non-Dylan acts; Baez, McGuinn, Elliott, and even Joni Mitchell are seen only fleetingly in the vintage footage. What’s here, however, has its value, even if it might be something of a lost opportunity to make the history as accurate as it could have been.

11. Echo in the Canyon. The focus of this documentary is a little fuzzy, but basically it’s about Los Angeles rock of the mid-1960s, some (but not all, despite the title) associated with Laurel Canyon. In particular, it celebrates the music of the Byrds, Beach Boys, Buffalo Springfield, and the Mamas & the Papas. Members of all those acts (Roger McGuinn, David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Brian Wilson, and Michelle Phillips) are interviewed, as are some others with strong associations with that scene (producer Lou Adler, Graham Nash) and frankly mild ones (Eric Clapton). There are also very brief snippets of vintage footage. All of this, however, is interspersed with a tribute concert/recording of sorts that younger musicians did not long before this film’s release. Those include Regina Spektor, Norah Jones, Cat Power, Beck, and most particularly Jakob Dylan, who’s kind of the host of the production, conducting the interviews as well as being the central figure in the tribute ensemble.

As interesting as mid-‘60s L.A. rock is, there are enough serious flaws in the movie to fill up at least a paragraph. Not even taking into account that Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys had no strong association with Laurel Canyon, the film overlooks some important figures who did, like Love, the Doors, and the Mothers of Invention (the last of whom are only mentioned in passing). More significantly, the device of mixing the historical interviews/footage with a contemporary tribute concert is unnecessary, considering the covers aren’t as good as the originals, and how it takes time away from the subject matter of far greater interest. If all this sounds like the gripes of a curmudgeon who just wants to live in the past, bury himself in more arcane interview footage that will drive impatient listeners to their cell phone screens, and should be castigated for failing to appreciate the attempt to bridge history with a new generation of musicians and listeners, fine. Bring it on!

Yet even with the film’s modest length (a bit more than eighty minutes), there are bits that might be unfamiliar to those who’ve already heard a lot of the stories. For instance, McGuinn remembers the Byrds’ wardrobe changing to a more casual one after their faux-Beatles suits were stolen from Ciro’s on Sunset Strip, where they had an early residency. Stephen Stills reveals his composition “Questions” was partially inspired by rearranging some of the elements of Judy Collins’s “Since You’ve Asked.” A piece of footage I don’t remember seeing before has Neil Young explaining to Dick Clark how Buffalo Springfield formed after he and Bruce Palmer just happened to drive their Hearse by a car with Stephen Stills heading in the opposite direction. Ultimately it’s worth the price of a matinee ticket, and no more.

12. Sam Cooke, The Two Killings of Sam Cooke (Netflix). I saw a flurry of mixed reviews of this documentary when it first became available. Some unfavorably compared it to ABKCO’s 2003 doc Legend, or at least questioned the need for another one. While I wouldn’t rate this newer production as a major work, I think it’s okay, and has enough material and perspective not in the previous one to make it worth viewing. There are reasonably interesting interviews with some surviving peers and associates like engineer Al Schmitt, Smokey Robinson, and Friendly Womack, and if the talking-head clips with academics and historians aren’t as interesting, they’re not without value. There are plenty of seldom seen vintage photos and film clips (though these are quite short), and a few overlays of audio-only Cooke interview snippets.

The coverage takes in not only his evolution from gospel star to pop-soul giant, but also his associations with civil rights figures and Muhammad Ali. The final section on his death notes speculation that the mob and/or record industry figures might have been involved, but gives different sides of the issue, and stops short of finding a conspiracy given the fragmentary evidence. The chief frustration with the 75-minute movie is that it could have gone in more depth, not only by offering lengthier performance clips, but also by discussing a few more of his records, some hits not even gaining a mention. If you want that, however, there are two big books that offer that kind of detail, You Send Me (by Daniel Wolff with S.R. Crain, Cliff White, and G. David Tenenbaum) and Peter Guralnick’s Dream Boogie.

Also, the following documentaries came out in 2018, but I did not see them until 2019:

Conny Plank, The Potential of Noise (Cleopatra). Actually first screened in Germany in 2017, and released in the US in 2018. But Plank is not exactly a household name, so how about a review here? The German producer might be best known in the hipster world for working with several key Krautrock groups, including Kraftwerk, Neu!, Cluster, Can, and Guru Guru. His association with them is covered here, but some might be disappointed that it only occupies some of this documentary, since he produced quite a few other acts before his death in 1987, aged just 47. Those ranged from Scorpions and Ultravox to Killing Joke, DAF, Eurhythmics, and a few names who might not be too familiar to English-speaking audiences, like Gianna Nannini and Rita Mitsouko. Many of them are interviewed in this film, which is a straightforward mix of comments from associates, family, and friends with numerous (if brief) bits of archive footage of his more illustrious clients.

If there’s any structural twist to this documentary, it’s that it was co-directed by his son Stephan, who didn’t get to know his father as well as he would have liked before Plank died when he was a teenager. Stephan himself does much of the interviewing and narration, and in common with many artists, Plank comes off as a figure more concerned, sometimes to the point of obsession, with his work than his family. His devotion to recording led to the construction of his own studio in a barn in semi-rural Germany near Köln, where much of the music he produced was cut. His standards for music deserving of his attention and time led him, he states in an interview excerpted for this film, to turn down opportunities to work with the Cars and U2 (whose Bono he dismisses with a vague disdainful comment). If there’s anything seriously lacking in this generally satisfactory overview, it’s more of a sense of what made the Plank sound distinctive, especially since his records (especially the non-Krautrock ones) covered a lot of different territory.

Jeff Beck, Still on the Run: The Jeff Beck Story (Eagle Vision/Universal). While there’s some good stuff in this fairly straightforward and conventional documentary, I have to admit it lost me about halfway through. Not so much because of the reasonable quality of the film, but because Beck’s career hasn’t been so interesting after the 1970s, at least as far as the records he’s done. The first half does have coverage of his ‘60s and ‘70s work with the Yardbirds and Jeff Beck Group and his solo fusion efforts, though it’s not so in-depth that much will astound fans who know a lot about the guitarist. Its greatest value is that Beck, not always the most voluble of interview subjects, talks a lot about himself and his music throughout the documentary. So even some of the familiar stories, like how he got the sitar-like sound for “Heart Full of Soul,” are interesting to hear in his own words.

Associates like Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Rod Stewart, Jan Hammer, and Ronnie Wood are also interviewed, though a few of the guys testifying to Beck’s prowess, like members of Aerosmith and Guns’n’Roses, were not exactly his peers. As he hasn’t done landmark albums over the last few decades, the last part of the film kind of wanders through various observations from lesser known people who’ve worked with him during that time, along with bursts of performance clips dotting those years. There’s a little about his fascination with cars, but not so much that it takes over from music as the center stage.

Aretha Franklin, Amazing Grace. Technically this premiered at a 2018 festival, though it wasn’t widely shown until the following year. Actually this film of January 1972 Aretha Franklin performances recorded for her gospel album Amazing Grace was supposed to have come out back then, but was shelved because of problems syncing the audio track. Now those technical difficulties aren’t apparent, and though Franklin blocked the release, after her 2018 death the film could finally be seen. Directed by noted director Sydney Pollack, it’s a pretty straightforward document of the performances at the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles, accompanied by the Southern California Community Choir. The band includes top session players Bernard Purdie (on drums) and Chuck Rainey (on bass), and gospel star James Cleveland performs a bit during the proceedings.

As respected as the Amazing Grace album was by critics—and as big a seller as that LP was, reaching the Top Ten—I don’t find the material nearly as exciting as Franklin’s classic soul music. It’s interesting, though, to see her performing in a pretty small church, with a largely African-American congregation as audience, though Mick Jagger and Charlie Watts can briefly be spotted. Her father C.L. Franklin, himself a respected gospel singer, also gets on stage for a bit. For secularists like me, the highlight is her gospelization of Carole King’s “You’ve Got a Friend.”

John Lennon, Looking for Lennon (Echo Bridge). Will this documentary tell you much about John Lennon’s childhood and teenage years if you’ve read widely about the Beatles? To be a snob, no. Just the Beatles biographies of Hunter Davies (who’s interviewed in this film) and Mark Lewisohn will tell you a lot, and (especially in Lewisohn’s case) quite a bit more, than can fit in a 90-minute movie. It’s made more awkward by scenes with a few talking head experts/academics who tell part of the story, without much charm or revelatory insight, while walking among Liverpool/Lennon landmarks.

So why give this doc a look? It does have interviews—albeit many so brief they’re more like soundbites—with quite a few people who knew Lennon growing up, some of whom have never or seldom been quoted in books or seen on film. That includes some of the surviving Quarrymen (even the most obscure “original” one, Bill Smith) and the late promoter Sam Leach, though Astrid Kirchherr, who was almost as important as any early Beatles associate, speaks for just a few seconds. There are also quite a few photos, many well known and often reproduced, but quite a few that are both unfamiliar and interesting. Should you not know much about Lennon’s early life, this will give you a fair overview. Otherwise, it’s a marginal addition to the wealth of footage/analysis devoted to him and the Beatles.