There was a lot more talk about Kansas City than usual in San Francisco last month, since the Giants were playing the Royals in the World Series. It came as something of a disappointment – no, an outrage – that at no time did the networks play the classic ‘50s rock song “Kansas City.” It even opens with the lyric “goin’ to Kansas City”! It was good enough to be used when the Phillies went to Kansas City to play the Royals in the 1980 World Series, and it’s more than good enough now, 55 years after it topped the charts.

For those who found the song “Kansas City” playing in their head as the World Series played out, there was often some understandable confusion as to what version should be playing. The most famous one is the single by Wilbert Harrison that went to #1 in 1959. The second-most-famous one, and perhaps almost-as-famous one, was recorded by the Beatles in 1964 for their fourth LP. Yet the Beatles’ version sounds almost totally different from the Harrison one. How did that happen?

The original version was written by two 19-year-old white Jewish guys in Los Angeles, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Leiber and Stoller would go on to become one of the greatest songwriting (and production) teams in rock history, but at that point were just getting a foothold in the R&B scene. As Mike Stoller remembers in Hound Dog: The Leiber and Stoller Autobiography, “Jerry’s idea was that we’d give him this geographically specific but musically traditional blues.”

After some apparently mild arguing about how authentically blues Stoller’s melody was, they placed it with Little Willie Littlefield, who had some regional success with the single in 1952. Littlefield’s version – done more as a jump blues than rock’n’roll, rock really not having been officially born yet — isn’t too different from Harrison’s, though a couple of the more risque lyrics would be modified. In the first act that would cause confusion for decades when fans traced the origins of the tune, however, the title was changed from “Kansas City” to “K.C. Loving” by Federal Records co-owner Ralph Bass (who considered “K.C. Loving” a “hipper” title, again according to Stoller in Hound Dog).

On September 13, 1955, Little Richard recorded a cover that stuck pretty close to Littlefield’s version for the first verse, though in a bit more of an uptempo rock’n’roll style. But then, in the biggest wrinkle in the song’s evolution, he suddenly leaped into an improvised-sounding diversion, yelping “bye bye baby bye, so long,” interspersing a characteristic whoop in the middle. When he gets back to a verse of sorts, this also sounds like he’s making lyrics up off the top of his head, then making another detour to the “bye bye so long” bit. Indeed, this sounds kind of like a jam after the first verse gets out of the way.

Then on November 29, he cut a yet different version which – it’s obvious right from the opening riff – is the one the Beatles based on their cover on. Here Richard took so many liberties with the Leiber-Stoller original that it’s virtually an entirely different song, save for the very basic theme of going to Kansas City to find a girl and tie one on. He did retain the “bye bye baby bye so long” etc. bit from his previous attempt at the song, adding a yet different bit based around a “hey hey hey” chant. In all, this accounts for why the Beatles’ version is credited to Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, and Richard Penniman (Little Richard’s legal name), not just Leiber and Stoller.

Now go back to the 1950s, but this time, the late 1950s. Journeyman R&B singer Wilbert Harrison had been doing Littlefield’s “K.C. Loving” live, and recorded it for a March 1959 single, this time changing the title back to “Kansas City.” Possibly Harrison was unaware of Little Richard’s liberal “cover,” sticking fairly close to Littlefield’s arrangement, though the lyrics were slightly toned down – “gonna get me some” was changed to “gonna get me one,” and the reference to a “bottle of Kansas City wine” was so slurred that many DJs and would-be-concerned parents might never have caught it.

But “Kansas City” wasn’t just a faithful replica of Littlefield’s by-then rather ancient single. Occasionally there are covers that vary the original only slightly, but by significant enough degrees to make it a much different listening experience and indeed much superior recording. And there may be no better example than Harrison’s “Kansas City.” What made it a #1 pop smash, where the original hadn’t even made the R&B charts?

Well, Harrison’s version just rocked more. He pounded the piano to set a compelling groove that might have had its roots in jump blues, but was as locked-in as it gets. Put on Littlefield’s version, and it’s just another above-average R&B song; put on Harrison’s, and your foot can’t help but immediately start pounding along with it. Crucially, Harrison also eccentrically varies the intonation on the vocals on the final lines of the verses so that he sounds like he’s leaning in and out of the lyrics, almost as if he’s tempted to sing it like a ska song. And most crucially of all, Jimmy Spruill lets loose with a wailing guitar solo (goosed on by Harrison’s shouts of “ah, but you know yeah, must-tah!” — well, that’s what it sounds like — and “ohhh yeah!”) that might be rooted in the blues, but is most definitely rock’n’roll. The record shot to #1, just a couple months after the plane crash that supposedly killed rock’n’roll – though, as “Kansas City” and countless other records prove, the music was very much alive and well at the time when rock’n’roll had supposedly died or vanished.

But while it was #1 in the US, it didn’t chart at all in the UK. There the hit version belonged to Little Richard, whose “Kansas City”/“Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey” mutation (as it’s now titled on Beatles for Sale) made #26, not long after Harrison’s “Kansas City” climbed the American charts. It was “Kansas City”/“Hey-Hey-Hey-Hey,” then, that the Beatles and other British teenagers heard, and this was the arrangement that the Beatles began to play live as early as mid-1960, as its inclusion on group’s the earliest surviving setlist proves. Although “Long Tall Sally” is a more celebrated instance of Paul McCartney’s ability to match Little Richard in sheer intensity for upper-register raucous rock’n’roll singing, the Beatles’ interpretation of “Kansas City” is just as impressive in that regard.

There are, indeed, several versions predating the studio recording they cut on October 18, 1964. They did three versions for the BBC (July 16, 1963; May 1, 1964; and November 25, 1964), all of which were bootlegged before the November ’64 one came out last year on On the Air: Live at the BBC Vol. 2. An inferior alternate studio take came out on Anthology 1, and you can even hear a lo-fi but energetic one from September 5, 1962 before a live Liverpool audience at the Cavern if you look in all the places you’re not supposed to.

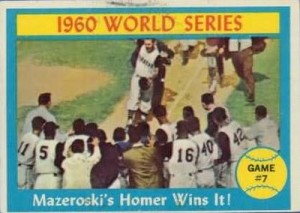

The Beatles also did it on September 17, 1964 when they, after getting an offer from Charlie Finley (owner of the Kansas City Athletics major league baseball team), added a Kansas City concert to their summer American tour. If it was good enough for the Beatles and Kansas City then, why wasn’t it good enough for Fox network last month?