Early this summer, I prepared materials for my upcoming community education course on the Who at the College of Marin. The Who Sell Out are a big part of week two, and that got me thinking about the relationship between major rock artists of the era (the LP came out in late 1967) and commercials. Not only does it seem like more bands than not did a commercial at some point; there are so many such commercials that it seems that very few groups refused an offer. The Who, of course, were at the forefront of this interchange, not only on The Who Sell Out (which featured the band-composed-and-played commercials between many of the tracks), but in “real life” as well.

The relationship between recording artists and commercials goes back to the very beginning of recording (and radio), of course, with many top blues, country, and rock musicians singing jingles when they appeared on the airwaves. Certainly it goes back to the beginning of rock; Elvis Presley cut a commercial for Southern Maid Donuts on November 6, 1954, a surviving tape of which, remarkably, still has not been found. Here follow the lyrics:

You can get them piping hot after 4pm, you can get them piping hot,

Southern Main Donuts hit the spot, you can get them piping hot after 4pm.

Elvis Presley’s jingle for Southern Maid Donuts hasn’t been found, but one that Johnny Cash did has, and is included on this compilation.

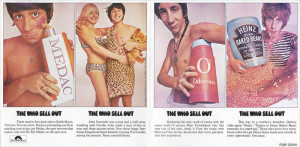

Never were commercials and rock as artfully combined as they were on The Who Sell Out, programmed to mimic a UK pirate radio broadcast (though they blew it by suddenly discontinuing the commercials a little into side two). There were even unused commercials that have showed up on the two-CD expanded edition and bootlegs. Obviously the jingles for Heinz and Charles Atlas referred to real products, but dummy me didn’t know until recently that the longest “commercial,” for Odorono, was a real deodorant. The name was so ridiculous that I figured it was a satire of a nonexistent cosmetic; turns out the joke’s on me.

There were many, many commercials cut at the time that weren’t satires, however — some even by the Who themselves. There have been enough, indeed, to fill up many CDs assembled by private collectors — eight volumes, in fact, in a series titled Psychedelic Promos & Radio Spots (though these also include commercials for records and commercials not sung or played by credited recording artists). That’s way too many to cover in a blogpost, but here I’ll mention some of the ones I’ve found most interesting.

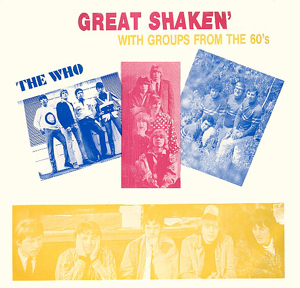

The Who did a couple commercials for Coke: a relatively (for them) conventional variation on the “Things Go Better with Coke” jingle with Beach Boys-like harmonies, and a far more satisfying grungy one where they chant “coke after coke after coke after coca-cola” with enough force to put you in a diabetic coma. (There were, incidentally, enough ‘60s rock commercials for coke alone to fill up a few CDs worth of jingles.) They also did one for the forgotten Great Shakes soft drink that used the rhythm of a song from their first LP, “La-La-La Lies.”

A compilation of Great Shakes commercials, highlighted by contributions from the Who and the Yardbirds.

As a greater stain on their discography, Pete Townshend did a most politically incorrect public service announcement for the US Air Force, at a time when opposition to militarism was heating up as death tolls from the Vietnam War skyrocketed. As “Happy Jack” (!) plays in the background, Pete gushes, “I just want to say that the United States Air Force is a great place to be. A great place to learn a space-age skill and serve your country too…see your United States Air Force recruiter.” Townshend doesn’t mention this in his recent autobiography, though according to Dave Marsh’s 1983 Who bio Before I Get Old, “Today, of course, Townshend is mortified that he ever did such a thing.”

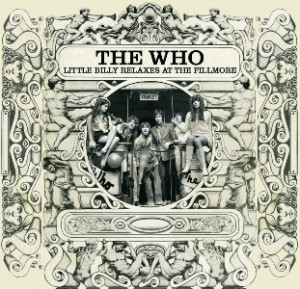

As karmic balance, the Who did an anti-smoking commercial, “Little Billy,” for the American Cancer Society. They were asked to do it by an agency that handled publicity contracts for both that organization and the band, and even considered issuing it as a single, if Townshend’s introduction to the number at an April 6, 1968 concert at New York’s Fillmore East is to be trusted. According to that intro, the society specifically requested it after hearing “Odorono.” Do these places have no sense of irony?

A complete song in the vein of the tunes about odd characters that populated their early repertoire (a la “Happy Jack,” “Whiskey Man,” “Silas Stingy,” and “Mary Ann With the Shaky Hand”), “Little Billy” never was used as a commercial. But it found a place on their 1974 outtakes collection Odds and Sods about a half dozen years later, and some fans got to hear it in concert shortly after it was written:

The Who’s live version of “Little Billy” can be heard on a tape of their April 6, 1968 concert at New York’s Fillmore East, long available on bootlegs like these, and the best-quality live recording of the band prior to 1969 that’s circulated.

On February 6, 1964, the Rolling Stones cut a brief Rice Krispies TV commercial at a get-it-over-with tempo wholly in keeping with their early frenetic R&B style, complete with wailing harmonica and sneering Mick Jagger vocal. It’s been reported this was co-written by Brian Jones with the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, but it certainly isn’t a sell-out musically, though the old-time blues guys probably wouldn’t have written songs about reaching for breakfast cereal first thing in the morning.

The Yardbirds did a commercial for Great Shakes that was a little more creative than most, part of it using a variation of the “Over, Under, Sideways, Down” riff. Some sources report that this is one of the few recordings done by the lineup featuring both Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page on guitar, with a recording date of October 19-20, 1966, but I haven’t been able to verify this beyond a shadow of a doubt.

Want harder stuff than Coke or Great Shakes? Cream did a commercial for Falstaff Beer that, like some of the nuggets detailed in this post, eventually found release on an archival collection. It’s built around something like the “Sunshine of Your Love” riff twisted into a pretzel, though Jack Bruce’s vocals are characteristically rich.

Getting back to Coke, the Moody Blues did more than one commercial for the world’s most popular (if hardly its most healthy) beverage. In fact, the first of these was done with their initial, far more R&B-inclined Denny Laine lineup, with stuttering Mike Pinder piano and their typically haunting vocal harmonies. “It’s workin’ out fine, whoa-whoa” improvises (I assume) Laine at one point, perhaps digging up inspiration from Ike & Tina Turner’s similarly titled hit to fill out the minute. The post-Laine jingles draw, as you’d expect, heavily on the mellotron that was such a primary feature of their late-‘60s sound.

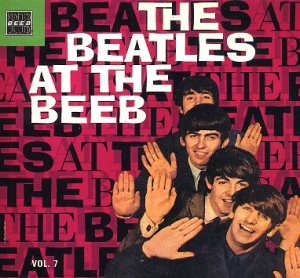

Rounding out our British Invasion citations, the biggest group of all, the Beatles, never stooped as low as to do a commercial to my knowledge, perhaps needing neither the exposure nor the money. It doesn’t exactly count, I know (especially as it aired on a radio network that didn’t even broadcast commercials), but they did do a half-minute in-house jingle for one of the BBC shows on which they appeared, Saturday Club. Sung to the tune of “Happy Birthday,” it’s been written that the chugging musical arrangement was based on Heinz’s then-recent (and only big UK) hit “Just Like Eddie.” That could be, though to me it sounds like a generic Eddie Cochran-inspired approach, Eddie being the then-recently-deceased rocker being paid tribute to by “Just Like Eddie” itself. Recorded on September 7, 1963, this was finally officially released last year on On the Air: Live at the BBC Vol. 2, though it had been bootlegged for decades.

The Beatles’ “Happy Birthday” jingle for the Saturday Club program appeared on this bootleg, about 25 years before it was finally officially released.

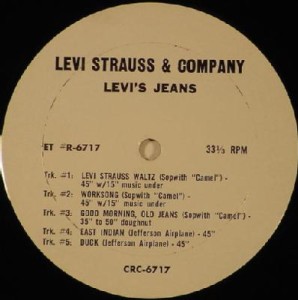

Although anti-establishment sentiment was supposedly a hallmark of much psychedelic rock, some of the most countercultural psychedelic stars did commercials for very commercial products. The most famous of these might be the ones Jefferson Airplane did for Levi’s, a couple finding official release on the 2400 Fulton Street compilation. As with the Who’s “Coke After Coke” jingle, one does wonder if they were taking the opportunity to subvert the whole process by producing as strange an advertisement they could manage while getting paid for it. One of their Levi’s ads features Grace Slick’s unmistakably strident vocals hailing white Levi’s over a heavy raga-rock drone; another is an almost Mothers of Invention-like chaotic sound collage.

This rare disc includes not only a couple Jefferson Airplane Levi’s commercials, but a couple done for the same company by a much more obscure San Francisco group, the Sopwith Camel.

Among the Airplane’s psychedelic peers, Quicksilver Messenger Service did a commercial for Chevrolet’s Camaro cars. The most political of the major Bay Area psychedelic bands, Country Joe & the Fish, did a commercial too — but not for a commercially available product, putting a brief spoof ad for LSD on their second album.

And though the Lovin’ Spoonful (from New York) got into hot water with Haight-Ashbury when two of their members cooperated with authorities after getting busted for pot in San Francisco, they were among the apparently few groups to turn down a Coca-Cola commercial, for the same reason they’d turn down the chance to be the star band in The Monkees. As Spoonful bassist Steve Boone writes in his new memoir Hotter Than a Match Head: Life on the Run with the Lovin’ Spoonful: “We might have made more money, or been able to trade off our name a bit longer due to the visibility of the show, but we probably would have sacrificed some self-respect and critical respect too. A similar argument came up later on when we turned down the opportunity to do what would have been a very lucrative, very high-visibility commercial for Coca-Cola.”

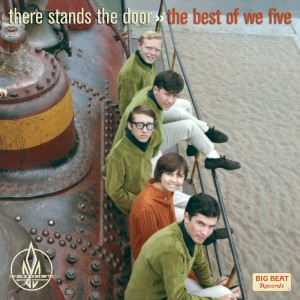

Contrast that to the attitude of one of the earliest San Francisco groups to have a rock hit, We Five of “You Were on My Mind” fame. Incredibly, after contracting with the McCann-Erickson agency in late 1965 to do some Coke ads, they spent “hundreds of hours attempting to provide what the agency requested, with each spot being rejected as either ‘too from contemporary middle of the road’ or, conversely, not ‘teenage’ enough,” according to Alec Palao’s liner notes for There Stands the Door: The Best of We Five. Says We Five bassist Pete Fullerton in the notes, “All they wanted was ‘when I woke up this morning, Coke was on my mind,’ and we just wouldn’t do that. That’s probably the biggest reason We Five split apart, because of the amount of work we put into it.”

A couple previously unreleased attempts at supplying Coke with a commercial are on this 2009 compilation of We Five material.

This doesn’t strictly count as a commercial, I suppose, but I was unaware until a few months ago that before they had a recording contract, the Doors did the incidental background music for, of all things, a Ford training film geared toward improving the customer service by employees at its sales outlets. Aside from periodic washes of instrumental music (there’s no singing or evident participation by Jim Morrison), it’s a positively excruciating 25 minutes, in line with the skeletal production values and dated do-gooder ethos of industrial training movies. There is one bit near the end where they go into a passage similar to the tune of a song on their fabulous 1967 debut album, “I Looked At You.” And it’s easily accessible now that it’s one of the extras on the Doors’ R-Evolution DVD in 2013, which compiled their promo films and TV appearances.

The Doors were indeed credited for the music they provided for a 1966 training film for Ford employees.

Another recording that isn’t really a commercial, or at least meant for the general public, was “cut” by Bob Dylan on May 12, 1965. This wasn’t a “song,” but a tape for a Columbia sales convention in Miami. Dylan plays it fairly straight, though some chuckles indicate he has a hard time taking this business obligation entirely seriously, declaring, “This is Bob! Uh…thank you very much for selling so many of my records. I wish I could be there with you right now at this minute, but unfortunately I’m all tied up.” Actually he was in London, attempting, quite unsuccessfully, to record “If You Gotta Go, Go Now” backed by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, with Eric Clapton on guitar. “God bless you all, and keep selling a lot of records!,” he concludes.

Moving to some artists who weren’t particularly known for their sociopolitical stances, one of the most entertaining psychedelic ads was waxed by the Electric Prunes for Vox wah-wah pedals. “You can even make your guitar sound like a sitar!” exclaims the overexcited salesman, the commercial introduced by a bee-buzzing riff all but identical to the one that launches “I Had Too Much to Dream Last Night.” Unlike many vintage rock ads, this has been in fairly wide circulation for more than 30 years, since its appearance on the ‘60s garage comp Pebbles Vol. 2. The first volume of that long-running garage series had already excavated the Shadows of Knight’s silly rave-up “Potato Chip,” a combination interview/musical performance on a cardboard disc included in bags of Fairmont potato chips.

Also in the Chicago area, the city’s best psychedelic group, H.P. Lovecraft, did a one-minute ad for Ban deodorant that made rather effective use of the precise sort of haunting vocal harmonies and eerie organ heard on most of their 1967 debut LP. I was quite excited to find this a few days ago, only to learn that it came out more than 20 years ago on the official compilation Oh Yeah: The Best of Dunwich Records. Well, you know, I haven’t heard everything.

The Left Banke did at least three commercials for three different products — Coke (in the “Things Go Better with Coke” format), Toni hairspray, and, less expectedly, Hertz Rent-a-Car. These are not so notable for any oddity within the commercials themselves, but for their very existence, since the group’s lifespan was so short that they only recorded a couple of LPs and a few odds and ends. These were even bootlegged on a three-song seven-inch a long time ago, each side playing the exact same three commercials.

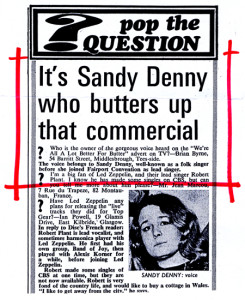

The great British folk-rock singer Sandy Denny is most known to the general public via her cameos on Led Zeppelin’s fourth album (where she appeared on “The Battle of Evermore”) and the orchestral version of Tommy (where she sings two lines as the nurse in “It’s a Boy”). A much less celebrated cameo was her vocal on a brief late-’60s commercial titled “We’re All Better for Butter.” This didn’t even make it onto her recent 19-CD box set, though it didn’t escape the attention of one of the leading UK music papers of the time (see below).

There were a whole lotta soul singers doing commercial back then, naturally, and one of the strangest was done by Smokey Robinson & the Miracles. In mid-1968, they proudly advertised their home town on “I Care About Detroit,” a promo single unavailable to the general public. He certainly wasn’t representing the true sentiments of the label he recorded for (and served as vice-president at), Motown Records, which even then had begun the process of moving from Detroit to Los Angeles.

There were also many instances in which acts appeared in a filmed commercial, or in some association with a product or organization — even unlikely ones like Pink Floyd, who did a recently unearthed video for “Jugband Blues” (with Syd Barrett) for the Central Office of Information, the UK government’s marketing and communications agency. Or David Bowie, who was in a Lyons Maid ice cream commercial in the late ’60s, when he was struggling to even have a record deal. That’s a whole other can of worms for another time and, perhaps, a different blogpost.