Living in the San Francisco Bay Area, I have access to a wider selection of produce, I would guess, than not only almost anyone from other parts in the US, but than almost anyone in the world. The long-established Berkeley Bowl, which now has two branches (one big enough to have a huge Bowl-ing alley-sized underground parking garage), might have more rows and rows of produce than any non-chain food store. The food comes not only from California, but from all over the globe:

On a typical visit, you can see grapefruit, melons, berries, and whatnot from as far-flung regions as Australia, New Zealand, and Japan, especially when they’re out of season in the US. I’ve seen mangoes from Mexico, Guatemala, and even Peru at the Bowl, along with other Central and South American regions. You want it, odds are they have it, though the quality and availability will vary according to the time of year.

Yes, it’s great to live in the early-twenty-first century, when you can eat almost whatever you want almost whenever you want. If you have the money, that is—an increasing problem if you’re paying Bay Area housing costs. But what of the other costs, especially to the environment?

Think about the transportation distances involved. If you buy a mango from Peru instead of some tangerines from Northern California, you’re adding more than 4000 “food miles,” as the term goes in sustainable agriculture studies. Edom tomatoes from Israel are flown from 7000 miles distant. That grapefruit from Western Australia came from more than 9000 miles away.

That’s a lot of fuel to get from “farm to fork,” to use another term bandied about in these discussions. According to the EPA, the 2,800 “food miles” a California tomato travels to be sold in Washington, DC adds 165,256 lbs. of carbon dioxide emissions. You can do the math, more or less, to figure out how much more CO2 is unleashed at greater distances.

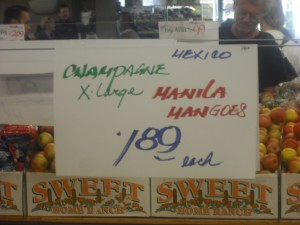

I don’t mean to pick on Berkeley Bowl too hard here. I don’t live close enough to the stores to go to them regularly, but I shop there myself when I go to the East Bay. According to its website, “the majority of our fruits and vegetables are grown locally”; “we buy from local farmers, the two wholesale markets in San Francisco and one in Oakland, and individuals who travel the agricultural areas of California looking for ripe, delicious fruits and vegetables,”; they have a large organic section, if not as large as the one for conventionally grown produce; and they do clearly mark the areas in which the food originates, as plainly seen here:

This did get me thinking of an issue I haven’t seen addressed in anything I’ve read, however. If you’re concerned about all those food miles adding up, should you not buy any of those Western Australian grapefruit at all? If it comes down to buying a mango from Mexico or Peru, should you go for the Mexican one, even if it’s not as juicy? Is it enough just to feel passing pangs of liberal guilt when you buy that tender-to-the-touch Guatemalan melon, instead of the hard-as-rock one that hasn’t logged as much mileage? Should you patronize stores that import produce from distant corners of the Earth, and should they institute some sort of policies or limits on how far they’ll go in search of that perfect persimmon?

I don’t know of any stores in the Bay Area or elsewhere that place such limits on transportation distances. A start, or at least a mitigation, is being sure to at least also offer a wide selection of locally grown goods, as Berkeley Bowl does. So does Rainbow Grocery, a large worker-owned San Francisco cooperative, which might have a far smaller produce department, but also puts far more emphasis on organic goods. Rainbow also labels the states and countries of origin, even listing the towns for produce grown in California.

Rainbow Grocery labels the state or country of origin of all of its produce, and the town if it’s from California. These grapefruit are from Oasis, a small town in Southern California.

“I don’t know that other stores place strict limits on how far their products travel,” says a member of Rainbow’s produce department. “We don’t. Preference is always given to nearby growers, and we buy farm-direct as often as possible. There are a few farmers who are given very high priority over other suppliers. Often, they’re people who run small operations, whose produce we love, and who have been supplying us for many years or decades. We’re really lucky to be in a region where we’re able to have close relationships with farms that grow an amazing range of produce, while they’re also deeply committed to growing it organically.”

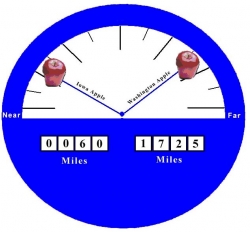

Locally grown produce, it should be stressed, does drastically cut down on the “food miles.” According to a study by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture, “locally grown produce traveled an average of 56 miles from farm to point of sale, compared to an average of 1,494 miles for 30 types of produce from conventional sources.” The page on its site with a PDF of the whole breakdown’s available here, and also by clicking on the nifty graphic below:

That study was done in 2003, by the way, and it’s a sad comment on the state of left-wing think tanks that there doesn’t seem to have been a similar one done since, as surely things might changed in the last decade. Even Green America, the leading organization for advocating responsible consumerism in the US, still cites the 56-mile figure from the study on its website. Internet searches for more updated studies generated just-mildly-less-outdated scholarly papers of the kind that take a frighteningly long time to download, or even display as a web page. The Leopold Center or someone should pick up the ball on this, though one would guess it’s hardly the study first in line for government or university funding, which might be part of the problem.

It should be added that part of the reason Rainbow, Berkeley Bowl, and other stores outside of the chain mainstream carry produce from far away because of consumer demand. That’s even true in the Bay Area, where much of Rainbow’s clientele is certainly much more socially conscious and politically progressive than the average shopper. “We do carry produce that was grown far away,” notes Rainbow’s produce department member. “Tropical fruits have to travel long distances, so our mangoes and pineapples are usually from Central or South America. Occasionally, we’re able to buy California mangoes. They’re expensive, but we carry them whenever they’re available. Our papayas are flown in from Hawaii. We have Mexican tomatoes when California can’t provide the types we want to carry.

“There is a huge demand from customers to make certain items available,” adds the worker I queried. “We buy imported pears and apples when domestic supplies are exhausted. (By this time of the year, if you want an organic pear, the Southern Hemisphere is kind of the only game in town.) We also buy imported blueberries. It’s a fact of modern life that we defy the seasons to satisfy our culinary and commercial wants or needs. There is disagreement within our department as to whether or when it’s appropriate to sell certain things, but we do our best to make responsible decisions.”

A key difference between Rainbow and Berkeley Bowl (among many other stores that could be compared to Rainbow) is, as stated earlier, that organic produce is far more prominent at the San Francisco cooperative. “For the Produce Department at Rainbow, it’s most important that our products are organically grown. For this reason, everything we carry is certified organic, wildcrafted (foraged produce, like wild mushrooms or fiddlehead ferns), or (in extremely rare instances) ecologically grown (grown and harvested according to organic guidelines, but lacking official certification). We carry NOTHING that was grown conventionally.”

If the organic produce isn’t locally grown, does that outweigh the effects of transportation over longer (sometimes much longer) distances? Should socially responsible buyers favor produce, even of the organic kind, whose journeys from farm to fork are shorter? Should they even decline to buy produce from far-off regions altogether—and if so, how far is too far? Mexico, Guatemala, or some other cutoff point (if measured from California)? Should there even be a carbon tax of some sort on produce, depending on how many “food miles” it’s traveled?

These are all questions I can’t answer—and, more importantly, that don’t seem to have been answered or discussed too much, either in academia or the socially responsible community that supports sustainable food consumption. One step toward finding those answers is bringing up the questions, and just this blog query has ignited some discussions at Rainbow. Watch this space for a follow-up, if more discussion at the cooperative’s meetings, formal or informal, result in any more info on how we should keep an eye on the fuel our food is burning up—even the produce is purchased with a social conscience.

UPDATE: Since I put up this post, I’ve found out that at least one health food store in the Bay Area not only posts signs with the place of origin of their produce, but also actually lists the distance it travels to the store. Good Earth Natural Foods in Fairfax, on one of Marin County’s main drags (Sir Francis Drake Boulevard), has signs such as the one below. Apologies for the blurriness, but you should be able to make out that this dill in its produce section was grown 201 miles from the store: