As time goes on and gets more and more distant from my favorite period of popular music, the reissues and vault finds get ever more specialized. They also get closer to the margins of what might be considered the core repertoire of major acts, and more and more obscure as far as artists who haven’t gotten much if any mainstream attention.

So it goes with my nearly Top Twenty list, where there are yet more live concerts by big stars (and part of seemingly continuous lines of them by Jimi Hendrix and the Doors); a huge expanded box by the Who (many other such boxes not on this list have been recently released as well); more live and rare early Renaissance than anyone thought was around; and a five-CD Heinz box, the very concept of which would have been unimaginable just a decade or two ago. Overdue career-spanning anthologies still come out, like the one for the Daily Flash, but there aren’t all that many such comps as noteworthy that are left in the wings.

While I don’t get too hung up on numbers and rankings, it was a fairly tough decision as these things play out to choose #1. Had none of the Doors’ March 1967 Matrix tapes ever circulated, that would have been an easy choice, but prior availability of tracks does factor into my list. Much of the Renaissance material was unheard, at least by me, which makes it more of a novel discovery, though that box is weighed down by some repetition and (though on less than half of it) subpar sound. There was no 2023 reissue that was clearly of such major importance that it was as easy a choice for the #1 spot, as, say, the first volume of Joni Mitchell’s Archives series and George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass were in recent years.

The Doors are by far the more important act, their 1967 tapes are definitely their most interesting live recordings, and the new box is the most complete collection of these, adding some previously uncirculating tracks. Ultimately that gives them the nod, though the top spot could have easily gone to the Renaissance collection, particularly if the welcome surprise of hearing some interesting stuff I didn’t know existed is taken into account.

1. The Doors, Live at the Matrix, 1967 (Rhino). A double live LP, Absolutely Live, by the Doors came out in 1970 while the group was still active, and there have been so many archival concert releases that even Doors fanatics have a hard time keeping track of them. Aside from their 1968 Hollywood Bowl show and the rather short, cover-dominated London Fog 1966, however—as well as a few lo-fi scraps that made it onto Boot Yer Butt!: The Doors Bootlegs—none of them predate 1969 save for Live at the Matrix, 1967. A double disc of material from their March 1967 shows at the San Francisco club came out in 2008, but this five-LP box lives up to the new and improved tag in a couple respects.

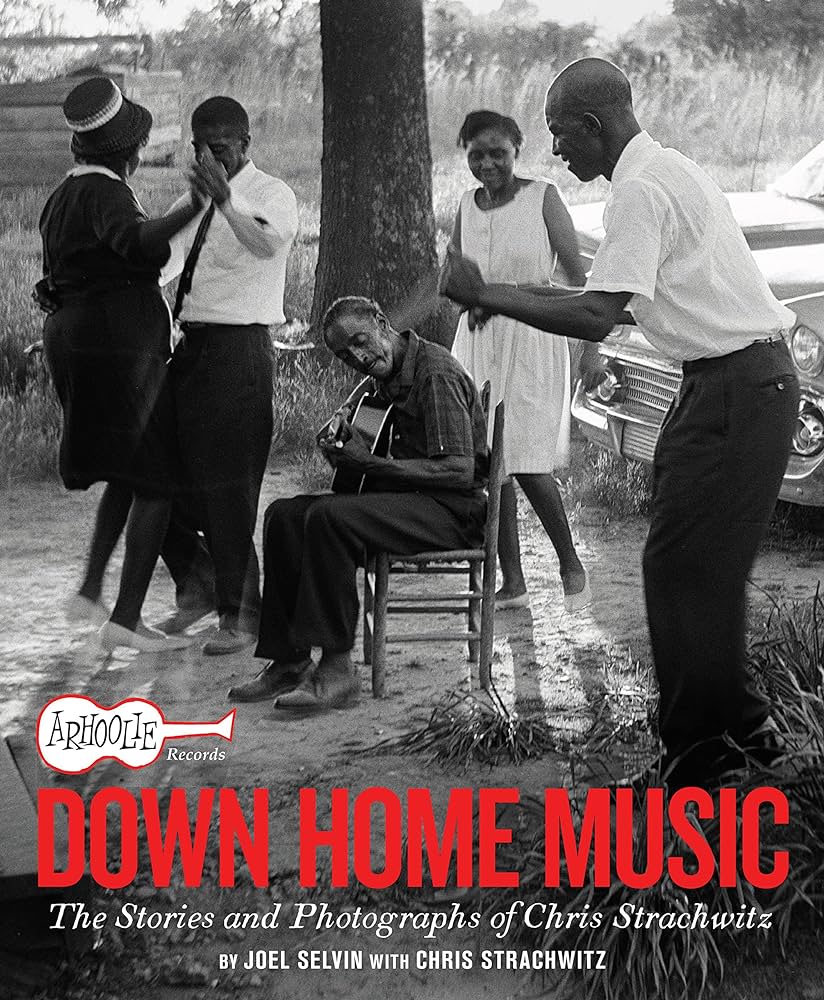

Crucially, the box has a lot more of what survives on tape from their March 7, 8, 9, and 10 Matrix shows. Most of the tracks gaining release for the first time have been in unofficial circulation for years, but this material’s taken, to quote Joel Selvin’s liner notes, “straight from reels of Scotch 201 quarter-track tape recorded at 7 ½ ips.” The 2008 compilation had been (it was belatedly discovered) mastered from third-generation copies, though it was thought at the time they were first-generation.

Yet what’s most important is that these are the only recordings that capture the Doors in peak form before they became stars and their set lists became more rigid and predictable. Their first LP had been out for a couple months, but “Light My Fire” wouldn’t enter the charts until three months after their Matrix stint. The Doors were still an underground act, and the audiences at the club were so small that, as guitarist Robby Krieger’s quoted in the liner notes, “We looked at it as a paid rehearsal. There were five to ten people in the club. We did it for ourselves.” Although the sound quality on these tapes is a little thin and distant, these are the best and most interesting of the live Doors recordings, both for the hungry, wiry intensity of the performances and the presence of quite a few songs that aren’t available in many or any concert versions.

They didn’t mail/phone it in, playing most of the songs from their debut album (no “Take It As It Comes,” “End of the Night,” or “I Looked At You,” sadly); every song from their yet-to-be-recorded second LP, Strange Days, except “Strange Days,” “Love Me Two Times,” “You’re Lost Little Girl,” and “Horse Latitudes”; and even one that didn’t make it onto vinyl until their third album, “Summer’s Almost Gone.” Plus a heap of blues/R&B/jazz covers, some likewise never part of their catalog while Jim Morrison was alive, like “Gloria,” “Money,” “I’m a King Bee,” “Get Out of My Life Woman,” and “Rock Me Baby.” Plus a few instrumentals to give Jim a break, including “Summertime” and a couple, Miles Davis’s “All Blues” and Milt Jackson’s “Bags’ Groove,” that to my knowledge have never before circulated anywhere.

Best of all, the band plays, and Morrison sings, with passion and spontaneity, even given that many of the songs (even the long version of “Light My Fire”) are rewarded with light tennis match-type clapping. “Moonlight Drive” (included here, like several of the songs, in two versions) differs from the Strange Days arrangement with a middle section where Morrison and Ray Manzarek sing improvised-sounding parts against each other, Manzarek playing organ instead of piano. “Unhappy Girl” opens with a long piercing organ solo that doesn’t appear in the studio version. Morrison asks to be shown the way to the next little boy in an alteration to “Alabama Song”—a change which, it’s safe to assume, would not have been allowed on a commercial release in 1967, even by a label as progressive as Elektra.

Although the songs were often enhanced by bass guitarist session players in the studio, the absence of a bassist means the arrangements are generally leaner here, and it’s interesting to hear Manzarek carrying the bass parts with the lower notes of his keyboard. Too, Ray had to play all his parts on an organ without utilizing piano for color and variation, which means songs like “People Are Strange” sound appreciably different.

As for the two previously uncirculating instrumentals, while naturally the band needed Morrison’s vocals to be at full power, they’re not without interest. The languid, repetitive riffs of “All Blues” are on the filler side, but an eight-minute forty-second “Bags’ Groove” (on the one-sided seven-inch that comes with the box) is actually pretty cool, the group hitting a nice jazz-bluesy sort of Doors-meet-the-MG’s groove. So is the lengthy (and previously available) instrumental “Summertime,” which the Doors arrange to suit their trademark hypnotic rock-jazz-blues style.

Not everything about this box is ideal. The sound quality isn’t remarkably different or better than the previous official and unofficial versions, though everything is now speed-corrected. Indeed, it isn’t as good as it is on the best and most historically significant officially issued Matrix tapes by other acts, those being the two LPs by the Great Society (with a pre-Jefferson Airplane Grace Slick) and 1969 Velvet Underground Live, Morrison’s vocals somehow not coming through as well as the singing does on those great records. The blues covers largely illustrate that early Rolling Stones-style blues-rock wasn’t the Doors’ strength. “Crawling King Snake” (later of course recorded for L.A. Woman) has some of the most amateurish harmonica (presumably by Morrison) to grace any release by a top rock act, though those bleats are brief and more amusing than annoying.

There is one standout among the covers, that being “Who Do You Love,” which the Doors would cut in a mellower version for Absolutely Live. The much earlier one on this box is good and preferable, with some nice swooping slide guitar and well-timed insertion of demonic organ breaks. Note that although the annotation describes this collection as the complete Matrix recordings, two versions of “Who Do You Love” purporting to be from the club in March have circulated. They’re easy to tell apart as Morrison’s vocal on the first verse is higher and nastier on the shorter one not included on this box, among other differences. One would guess the missing version might not have been taped at the Matrix, though it seems to be from the same era, and has similar fidelity. (A slightly edited version of this review will appear in a future issue of Ugly Things magazine.)

2. Renaissance, Live Fillmore West and Other Adventures (Repertoire). For a group of notable significance, the output of the original Renaissance—the lineup featuring ex-Yardbirds Keith Relf and Jim McCarty, as well as bassist Louis Cennamo, ex-Nashville Teens pianist John Hawken, and Relf’s sister Jane—was slim. There was just one album, 1969’s self-titled Renaissance, before the group’s personnel started to shift and splinter. By their third album, not a single original member remained. Renaissance itself had just five songs, though three were between seven and twelve minutes long.

This five-disc set does much to amplify their sparse discography, with four CDs of previously unissued live performances, TV and radio broadcasts, and demos, along with a DVD of British and European television clips. That’s a heavenly gift for fans, though it comes with some limitations. The sound quality is uneven, though the performances aren’t. And though there are a few songs that didn’t make the studio LP, there are inevitably a lot of multiple versions of the five that did.

The majority of the material comes from live concerts, the whole of the first disc featuring their March 6, 1970 show at the Fillmore West. While the instruments come through fairly well, there’s no denying that the vocals are on the submerged side. In common with many live tapes of plenty of acts from the era, the songs are stretched to markedly longer arrangements, “Kings and Queens” and “Bullet” lasting fifteen minutes apiece. The odd ghostly, almost avant-garde ending of the studio version of the latter wasn’t replicated in live performance. As a major bonus, however, in addition to all five songs from the LP, three others that didn’t make it were played. All of their compositions have the group’s idiosyncratic blend of rock, classical, and exotic non-rock styles, often layered with a tense, ominous mood.

None of the non-LP numbers are quite up to the level of the material on their studio releases, the eight-minute “No Name Raga” going into some less focused improvisation than was their usual wont. The nine-minute “After the War,” songwriting credited to “unidentified,” is hard to fully judge. It boasts some wailing Jane Relf vocals, but the extent to which they’re under-recorded is a deterrent to full listening pleasure, though there are some forceful riffs and wah-wah guitar, and McCarty’s drumming gets into more uninhibited soloing than he ever did with the Yardbirds. The two-minute “The Tao of Myself” is a two-minute improvisation tagged onto the end of “Bullet,” and the words Keith Relf are singing can’t be easily deciphered. (For that matter, the ways vocals were placed in the mixes and arrangements sometimes made it difficult to make out early Renaissance’s lyrics with exact precision even when they were recorded in classier audio.)

Disc two combines excerpts from concerts in Helsinki (May 1969) and Switzerland (April 1970) with a May 1969 version of “Kings and Queens” from a Swedish radio broadcast. It’s perhaps the least notable disc owing to less-than-sparkling audio quality, sticking to versions of just three of the five songs from the album. There’s also a brief Helsinki interview with Hawken and Keith Relf that just makes basic points that the group, which had only done a few concerts, was trying to do something different.

The sonic imperfections of the first two CDs might put them in the “for hardcore fans” only category, but that’s not the case for the other CDs. Disc three features more than forty minutes of material from a February 25, 1970 Cincinnati concert, and while the fidelity might have been a little too dull to make the cut for the usual standard official live album, it’s appreciably better than what the preceding two discs offer. Crucially, it has not only every song from Renaissance except “Innocence,” but also has far better sounding versions of “No Name Raga” and “After the War,” although “Bullet” lasts less than half of what it does on the Fillmore tape.

Cincinnati’s Music Hall might not have had the glamour of the Fillmore West. But these recordings, made just a couple weeks earlier than the ones from the Fillmore, are a decidedly better representation of the band—who play and sing well everywhere in this package, regardless of the variable technical qualities of the tapes. Disc three is completed by the similarly acceptable-fi audio of 1969-70 British and European TV spots, though those are better experienced as the film clips featured on the DVD.

The first half of disc four has decent-sounding BBC radio broadcasts recorded in October 1969 and March 1970, with versions of all songs from the debut LP except “Wanderer.” Of most interest, there’s also (from the March 26, 1970 taping) a Jim McCarty original, the delicate folk-classical Jane-sung “Face of Yesterday,” that’s the sole song on the entire package that found a place on Renaissance’s second studio album, 1971’s Illusion. There’s also a brief Keith Relf interview where he explains how different factions in the Yardbirds led to a different sound he and McCarty wanted to explore with Renaissance.

The second half of disc four contains the least characteristic, yet in some ways among the most interesting, tracks on this compilation. These nine “rarities and demos,” as they’re titled here, are almost an entire studio album of its own, though they were recorded at various times and with different combinations of musicians. It would have been nice to have exact personnel listings and dates, if they even exist. But Cennamo’s comments in Chris Welch’s lengthy liners indicate most were done between the Yardbirds’ split and Renaissance’s formation, though some were done significantly later.

Whatever their precise origins, they show a somewhat folk-poppier, less ornate, and more concise side of the band, and a very good one, even if some fans might prefer their more avowedly progressive efforts. One highlight, the buoyant but bittersweet “Line of Least Resistance,” showed up a few years ago on Repertoire’s collection of Keith Relf rarities, All the Falling Angels. So did “I’d Love to Love You,” a lovely acoustic duet between the Relfs, and “Together Now,” though this a different (and inferior) version with added orchestration.

Generally these studio recordings afford greater room for Jane Relf’s vocals, both in quantity and range of expression. Certainly one peak, not only of this anthology but of her whole career, is her glowing interpretation of “Carpet of the Sun,” which a later lineup of Renaissance would record in a much more bombastically arranged version, with Annie Haslam on vocals, on a 1973 album. Cennamo states in the liners that this Jane-sung version was cut “after the original Renaissance broke up,” which might make it the latest track on this compilation.

But most of these demos and rarities have an enticing haunting, melancholy-with-rays-of-sunshine bursting through feel, and would make a nice (if short) album of its own, despite its disparate sources. (McCarty’s “Prayer for the Light,” for instance, comes from the obscure Schizom soundtrack.) As a whole, they point to attractive directions the original Renaissance lineup could have explored more fully, whether during their brief lifetime or had they stayed together longer. They also more fully show the appeal of Jane’s singing—in a different way than her brother, though she likewise didn’t have the power of more celebrated British vocalists, she projected personal, enigmatic emotion that more than made up for that.

While it would be a cliché to propose that the whole set’s worth buying for the 40-minute DVD, especially with respect to collectors’ budget considerations, the one that closes this anthology comes close to deserving such an accolade. Besides well-preserved color clips of 1970 broadcasts of performances of “Island” and “Kings and Queens” on the Germany TV program Beat-Club, there’s a much less frequently seen fourteen-minute BBC mini-documentary from late 1969, also in vivid color. This shows the original group working in the studio, where producer Paul Samwell-Smith and engineer Andy Johns can also be seen; in more casual settings, with brief interviews with band members; and at a live performance of “Island” in London’s Revolution Club in October 1969. In black and white, but in good shape, is a clip of the band in Paris in January 1970, again performing “Island,” obviously a favorite of the group and, apparently, television programmers.

This would have arguably worked better as a three-disc set without the first two discs, as higher-fi versions of almost all the songs from the first pair of CDs are heard on the final three. It’s also true that the abundance of multiple versions—seven apiece of “Island” and “Kings and Queens”—makes this too much to take in at once. Yet some fans would argue, with some reason, that if you’re going to have some rare material, you might as well have it all. It’s all here, and if early Renaissance was in some ways not as immediately accessible as far more famous post-Yardbirds projects by their three celebrated guitarists, this does reward patient listeners. It also boasts its share of incandescent songs and passages that strike home right away. (A slightly edited version of this review appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

3. Joni Mitchell, Archives Vol. 3: The Asylum Years (1972-1975) (Rhino). The third volume of Mitchell’s five-CD box sets of almost entirely unreleased material actually spans late 1971 to 1975, to be technical. The title refers to years during which she was on Asylum Records. Like the previous two boxes, it’s a deft mix of demos, outtakes, and live recordings, including a few on which James Taylor sings or Neil Young plays, though Mitchell’s the focus on those. The one previously released track might have been missed even by Joni collectors, since “Raised on Robbery,” recorded in 1973 with Neil Young & the Santa Monica Flyers, only came out on Young’s Archives Vol. 2: 1972-1976.

Unlike the majority of listeners, I’m a much bigger fan of Mitchell’s earlier work, an era spotlighted on the previous two boxes, which spanned 1963-1971. But I liked this more than I expected, in part because the different nature of the sources ensures there’s more variety than there is on any studio or live Mitchell album from this period. If the studio LPs (For the Roses, Court and Spark, and The Hissing of Summer Lawns) had more polished production, the songs from those albums certainly don’t suffer in earlier and often plainer musical settings. Personally I prefer the less elaborate productions, especially to those using the slicker fusiony sounds of Tom Scott & the L.A. Express, though that outfit can be heard on some of the numerous songs from her March 3, 1974 concert at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in Los Angeles.

There’s enough material from that show and her February 23, 1972 Carnegie Hall concert to have made two separate albums, and these (as well as scattered much shorter excerpts from other live appearances) mix then-new compositions with older songs that were already favorites, like “Big Yellow Taxi,” “Woodstock,” Both Sides Now,” and “The Circle Game.” Some of her between-song raps are quite long and spacey, including an unexpected reference to the Performance movie. A studio medley duet with James Taylor of “Bony Moronie,” “Summertime Blues,” and “You Never Can Tell” demonstrates both that Mitchell had a genuine love for early rock and roll, and that it wasn’t her strong suit as an interpreter or performer.

The more (at the time) recent and less familiar compositions are the highlights, however, though some similarity in her approach on quite a few songs in this era means this wouldn’t qualify as the most consistent Mitchell listen – not that this was the intention of an archival box like this. Some of the better and/or more interesting items include a pre-For the Roses live acoustic version of “You Turn Me On I’m a Radio,” and an outtake of the same tune backed by Neil Young and the Stray Gators; a band-less demo of her biggest hit, “Help Me”; good demos and alternate versions of a couple highlights from Hissing, “In France They Kiss on Main Street” and “Dreamland”; and likewise the demo and Neil Young-backed versions of a Court and Spark highlight, “Raised on Robbery.” Best of all is the Court and Spark outtake “Bonderia,” in which Mitchell scats wordlessly with an unusual nearly middle eastern-gypsy-ish melody that’s almost experimental by her standards. Along the same lines, “Sunrise Raga” is offbeat as it’s nearly instrumental save for some wordless singing, and Mitchell’s backed by bongos on an Indian-flavored piece. Both tracks make me wish she’d done more such ventures.

Like the previous Archives boxes, Cameron Crowe interviewed the singer for the liner notes. While some might wish she’d been grilled in greater depth about some of the specifics on these vault retrievals, it’s enough of a miracle she can speak at some length to an interviewer given her recent health scares. While this might not be my favorite volume owing to my personal tastes, in its selectivity and packaging it’s up to the standards of its predecessors, and the series as a whole is already established as one of the best of its kind in those regards.

4. The Who, Who’s Next/Life House (Polydor). This is basically a superdeluxe edition of Who’s Next, though much of the material was originally intended for the unfinished rock opera Life House (as it’s now apparently spelled, rather than Lifehouse). How does it not rank higher or at the top of this list, considering I wrote about it in about half of my book Won’t Get Fooled Again: The Who From Lifehouse to Quadrophenia? It’s not the greatest value for money, boasting a $250-300 price depending on where you get it. More importantly, the extra material isn’t always that exciting, though at least Pete Townshend refrained from putting on post-1970s re-recordings or interpretations of Life House elements. The original Who’s Next album is one of the discs, and a Blu-ray offers mixes of tracks (all heard elsewhere on the set) that some consider higher-fi than what’s possible on average stereo systems. Everything else was not on the Who’s Next LP, though a fair amount of it’s been released elsewhere.

The most interesting material is found on the two CDs of Pete Townshend demos. Much of it’s done the rounds on limited edition release and bootlegs, but they include solo versions of much of the material on Who’s Next that have a different, sometimes more personal, less glossy, and vulnerable cast than the highly polished group studio tracks. There are also some songs that didn’t find release by the Who or sometimes anywhere at the time, with the tender, acoustic folk-based love song “Mary” and the wistful “Time Is Passing” being highlights. An early iteration of “Baba O’Riley,” titled “Teenage Wasteland,” uses a far different melody for much of the performance than the later familiar version. But most of the songs not eventually reworked for Who’s Next aren’t as good as what was selected for that album, “Pure and Easy” being a notable exception. The most unfamiliar of these, “Finally, Over” and “There’s a Fortune in Those Hills,” don’t leave much of an impression.

This box is one of these infrequent instances where, for my purposes, limiting it to these two CDs would have been more enjoyable listening (not to mention more affordable) than working through the whole set. There’s a disc of their first go at the album at New York’s Record Plant in early 1971; alternate versions cut at Olympic; and quite a few non-LP singles and outtakes from 1970-72, sometimes in longer unedited versions, though all of these have appeared in some mixes/edits on other archival compilations. Some fans have already offered different and much more enthusiastic assessments, but I don’t find any of the alternates too appreciably different than the final arrangements, let alone superior to them or on the same level. The non-LP singles and outtakes include some very good songs (“The Seeker,” “Join Together,” John Entwistle’s “Heaven and Hell”) and a bunch of decent-to-okay ones (the Roger Daltrey-written 1970 B-side “Here for More” is underrated), but the unedited longer versions don’t significantly add to their quality.

There are also two CDs of live recordings from London’s Young Vic on April 26, 1971, and two CDs of live tracks from December 12, 1971 in San Francisco. Acknowledging that many Who fans groove mightily to live recordings of the band from this period (and not just Live at Leeds), these aren’t my favorite ways to experience their music. The execution can be blustery, the songs overlong, and the odd unexpected covers (“Bony Moronie,” Marvin Gaye’s “Baby Don’t You Do It,” and Freddie King’s “Going Down”) unremarkable. Overall, there are just too many multiple and not-terribly-varying versions of songs throughout the box to make for listening that’s as stimulating as it might seem on paper.

Also in the box is a 102-page hardback book of deeply researched liner notes that does a lot to help illuminate the stories of both the unfinished Life House and the album it morphed into, Who’s Next, as well as the many extra tracks recorded by the band between 1970 and 1972 (excepting Live at Leeds recordings). The newly written graphic novel based on Life House that’s also part of the package is not as essential and, in my view, inessential. The rare period memorabilia in an LP-sized sleeve, including reproductions of posters and concert programs, is nice but not amazing. If omitting the Blu-ray and the quite sizable graphic novel would have lowered the list price considerably, I would have preferred such a revision.

5. Various Artists, Tape Excavation (Independent Project/P22). This came out in LP form in 2020, but there are reasons to include this on a 2023 list. Even if you’re the kind of collector who gets in line for Record Store Day releases at dawn, you might be frustrated by trying to acquire the LP-only release if you don’t already have it. It was available only as limited editions that added up to 600 copies. More importantly, this CD version adds eight tracks to the original fourteen, now making for a total of twenty-two. It compiles previously unreleased tracks from various Bruce Licher musical projects spanning 1980 to 2019, including material from his most famous band (Savage Republic); pre-Savage Republic outfits Project 197, Bridge, and Final Republic; and post-Savage Republic projects Scenic, Lanterna, Lemon Wedges, Bank, and SR2, along with post-Savage Republic Licher solo recordings. A booklet with liner notes explains the origins of the tracks.

Tape Excavation’s selections are actually of similar quality to Licher’s previous official releases, even if the fidelity and polish might not be as high on a few tracks (particularly the earlier ones). Although it covers four decades, there’s a continuity in the eerie instrumental textures, which both use conventional instruments (especially Licher’s unusually tuned guitar) and blend them in unconventional ways. The earlier efforts bear some traces of early-‘80s post-punk dissonance, yet are likely to appeal to people who don’t usually like post-punk, at least if my own tastes are an indication. There’s even some appealingly cheesy new wave keyboard on Final Republic’s “Chase,” though the same group was responsible for the foreboding waves of overlapping reverb dominating “The Unknown.” The earlier of the additional eight tracks tend to be noisier and more industrial in nature than the original core fourteen.

Licher focused more on sort of post-punk equivalents to surf music with elements of psychedelia and middle eastern melodies as time went on. His pair of 1997 solo demos are of special note; “Cedar” is worthy of exotically dreamy Ennio Morricone-like soundtracks, and “Tundra” can’t help but sound like an end-of-the-century takeoff on the Byrds’ “Why.” The later excursions might be less edgy and frenetic than his ‘80s endeavors, but maintain his knack for atmospheric instrumentals that are more mature yet not at all wimpy.

The tracks of later vintage added for the CD fall into this area, highlighted by Exploratorium’s “The Atmosphere” and the dreamy yet slightly foreboding late-‘90s home recording “SF Cima Song,” a variation of a song from Scenic’s Incident at Cima album. The most recent of the added items, the 2009 solo home recording “Mesopotamia” and the 2017 solo home recording “There Is Always a Light Which Will Illuminate the Way, Even in the Darkest of Times,” are also up to the standard of the selections on the original LP, as spooky instrumentals evoking the kind of photos of desolate landscapes found in many of the booklet’s illustrations. Licher went through dozens of boxes of recordings to cull these tracks, and if even a small percentage of these approach Tape Excavation’s standard, a series of archive releases would be welcome.

6. The Daily Flash, The Legendary Recordings 1965-1967 (Guerssen). It’s hard to know where to rank a compilation on which the best half dozen or so tracks are so much better than the other dozen or so. On the basis of their handful of previously available rare singles and outtakes, the Daily Flash were among the better early folk-rock groups, with particularly outstanding covers of Ian & Sylvia’s “The French Girl” and Eric Andersen’s “Violets of Dawn,” as well as searing early psychedelia on “Jack of Diamonds,” which opens with an unholy blast of feedback. They had good vocal harmonies and guitar-oriented arrangements that were polished without getting too slick, creating the impression they could have been significantly bigger if they’d gotten more breaks.

A whole LP’s worth of material, including all of the above songs, appeared back in 1984. But this 19-song comp was eagerly awaited as it includes about ten cuts that haven’t been easily available, and in some cases never before issued. Yet none of the extras are in the same league as most of what appeared on that 1984 LP, I Flash Daily. The folk-rock versions of Dino Valenti’s “Birdses” and Bob Dylan’s “Let Me Die in My Footsteps”—themselves hard to hear in versions by their composers back in the mid-1960s—are just okay. Some of the other folk-rock updates of folk tunes, like “When I Was a Cowboy,” are disappointingly forgettable. Only a couple of original compositions (both by Steve Lalor) are here, and while “Barbara Flowers” isn’t bad poppy folk-rock, the previously unissued “Again and Again” doesn’t make much of an impression.

This Seattle group’s failure to write much, or very interesting, original material was the biggest factor in their failure to rise to the heights of the better folk-rock groups of the time. Like Buffalo Springfield, for instance, who were also produced and managed by Charlie Greene and Brian Stone (and whom Daily Flash guitarist Doug Hastings joined for a bit when Neil Young left the Springfield). Despite the excellence of their best sides, they just didn’t have what it took to be a major band, as much as folk-rock fanatics like me might have wished this comp to prove otherwise. But it does, after a gap of many years, fully represent their legacy, with thorough if occasionally drifting liner notes untangling their history and what happened when, including recording dates. There are three versions of Dylan’s “Queen Jane Approximately,” though there’s a purpose to the repetition: two different versions were released on singles, and the third one’s a live recording.

7. Various Artists, One Mile from Heaven (Mapache). In the 1970s, there were loads of privately pressed singer-songwriter albums—many, perhaps most, of them poor and amateurish. There were also some decent and, on rare occasion, striking ones, or at least some striking tracks here and there on such releases. This twenty-track double LP curates some of the most noteworthy, with a couple (from Jim Sullivan in 1969 and Bobb Trimble in 1980) falling just outside the ‘70s. In the words of Daniel Resines’s liners, “It’s a compilation of hardly known (if not completely unknown) songs that nobody was waiting for—the sheer opposite of a greatest hits album.” In other words, the kind of thing that many collectors of vintage rock esoterica are waiting for.

But while none of these are household names, some of them are known, to UT readers at any rate. Maitreya Kali (aka Craig Smith) is a star in UT’s world, in large part due to our publisher/editor’s excellent book about him, and his “One Last Farewell” leads off this collection. Another star of sorts in our alternate universe is Merrell Fankhauser, whose prime was just honored with a six-CD box. Gary Higgins, Michael Yonkers, and Jim Sullivan have their own smaller cult followings; Alicia May and Chuck & Mary Perrin have been honored with CD reissues of their albums. At least half the artists, however, are apt to be unfamiliar to most collectors, other than the kind who write reviews for the fine reference books overseen by Richard Morton Jack and the late Patrick Lundborg.

This sort of privately pressed singer-songwriter fare could hardly be called a “scene”—few of them knew each other, and few listeners heard these records when they were released. There is, however, a unifying thread, at least when you hear them with half a century or so of distance. Though not nearly as desolate or outsider-ish as many “loner folk” efforts, there’s a bittersweet after-the-party feel to much of the material. There’s often a pensive, subdued air, but it’s not exactly laidback or mellow. And while these generally had much lower recording and promotional budgets than mainstream ‘70s singer-songwriters on “real” labels did, the sound is always professional, and usually nearly or on par with major label efforts of the period.

At the same time, it’s far enough removed from the bigtime music business to ensure a lot of idiosyncrasy and, within this anthology, diversity. Maitreya Kali’s “One Last Farewell” does stand out as a highlight for its spookiness, but other selections worth noting include Billy Hallquist’s eight-minute “Persephone,” which builds to an extended anthemic choral climax nearly worthy of Fairport Convention’s take on “Percy’s Song,” to cite a rough comparison. Yonkers’s “And Give It To You” is far more delicate and sensitive than his more famed, yet more bombastic, earlier and far heavier, far more electric-oriented recordings.

Joni Mitchell fans are likely to enjoy Alicia May’s “Summer Days,” which was recorded by the same engineer Mitchell used, Henry Lewy. Naomi Lewis’s “More Beautiful” is classy melancholy mid-‘70s singer-songwriting with a more effectively deployed sparse arrangement than most of her more celebrated peers were prone to use. Carm Mascarenhas has, according to the liners, been compared to vintage Van Morrison, though I hear some of fellow Canadian Neil Young in his approach. For something a bit more eccentric, there’s Michael Angelo’s “Field of Lonely Eyes,” which blends nice close vocal harmonies with eerie synthesizer on a cut that’s more homespun and lo-fi than most of the other selections, but pleasantly so.

While hardcore collectors might insist you need to experience these artists with their full albums, this works well as a sampler whether you want to go deeper or content yourself with some of the cream of this niche genre. If you don’t specialize in that niche, the appeal of the individual tracks might be enhanced by hearing them in similar yet versatile company, rather than on full albums by the artists that some might find wearisome to take in all at once. The booklet has background info on all of the performers, with pictures of most of them, and reproductions of all the LP covers from which the material was drawn. (A slightly edited version of this review appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

8. David Blue & the American Patrol, The Lost 1967 Elektra Recordings & More (Hanky Panky/Mapache). Blue’s self-titled 1966 Elektra debut LP was one of the most blatantly early electric Dylan-inspired records, at a time when there was no shortage of Dylan imitators. He did a second, but unreleased, album for Elektra in 1967 with, or at least credited to as with, backup band the American Patrol. Eight of the ten tracks that would have comprised that album are this vinyl-only LP release, along with three acoustic folk tracks he contributed to Elektra’s 1965 various-artists compilation album Singer Songwriter Project, where he was billed under his birth name, David Cohen.

Blue still sounds derivative of Dylan to some extent on much of the 1967 material, but he was taking steps toward finding more of his own voice, both as a singer and a songwriter. “23 Days in September” (which he’d re-record in a more laidback version on his 1968 album of the same name), “Scales for a Window Thief,” and especially “Best of Your Childlike Smiles” are rather nice, if still slightly Dylanesque, pensive folk-rock. There’s a wistful quality to Blue’s softly intoned vocals and more bittersweet melodic turns than most circa-’66 folk-rock (though this was taped in 1967) of this sort had. He gets into more playful, lighthearted moods, with variable but basically acceptable results, on some of the other songs; “Anna” is the best of these, and “You Need a Change” has a slightly ahead of its time country-rock tinge.

It’s unfortunate, however, that “Vaudeville Blues” and “Dr. Smith’s Electrical Light Machine” have a cringeworthy dated vaudeville rock feel, along the lines of so many similar tracks from the time from bands that seemed to feel they should put one such cut on their LP, as if they had to prove their diversity. It’s doubly unfortunate that two other tracks from the unreleased LP, “Anything You Find on the Floor Is Yours” and “Tell Me What It’s Like When You Get Back,” were not made available for this release, as they have a decidedly rougher and bluesier, almost garage rock feel than the rest of the material. As far as demonstrating versatility goes, they’re far better than the vaudevillian tunes, and one wishes they could have been included, or even included at the expense of the vaudevillian numbers. They’d also be more interesting than the pretty run-of-the-mill folk performances from Singer Songwriter Project, an LP that hasn’t been too hard to find (though some editions exclude the tracks by Richard Fariña, which are the best on that compilation).

Who loses in this exclusion? Only fans and history. Had they been possible to add to the tracklist, this LP would have ranked a notch or two higher. History is given, at least, by Mark Brend’s extensive liner notes, decorated by some rare pictures and graphics. This was issued in a limited edition of 500 copies, the same label also putting out a 500-copy vinyl run of Blue’s debut LP at the same time.

9. Los Shakers, ¡Shaker Mania! (Guerssen). Los Shakers, or the Shakers as they’ve sometimes been billed, were the finest Uruguayan rock group of the 1960s, and indeed probably the best one in South America. Some might feel this is damning with the faintest of praise considering how much distance in quality there was between South American rock and North American (and British) rock. But singing in both Spanish and accented English, they were also among the better explicitly Beatles-influenced groups from anywhere in the globe. Plenty of people wouldn’t count this as a major asset either, and it’s easy to imagine some rock critics making fun of how heavily derivative their records were, not to mention the accents and awkward English phrasing. But their records were pretty enjoyable, if no match for what the Beatles (or even the better bands with some similarities to the early Beatles, from the Hollies and the Bee Gees to the Beau Brummels) did.

Plenty of Shakers music has actually been readily available in English-speaking countries for a long time, both on CD and through an English-language LP Audio Fidelity actually issued in the US in the mid-1960s, Break It All. For those such as I who do care about their catalog, this (so far vinyl-only) compilation offers something different, focusing on non-LP singles and rarities, even including three previously unreleased tracks. As a whole they’re not quite up to the level of the best Shakers CD compilation, Big Beat’s 2000 release ¡Por Favor (compiled, like this LP, by Alec Palao). Nor does it offer anything especially different from what’s been more commonly available. It’s just good sub-Beatles ‘60s pop-rock, sometimes (though not often) with a more South American influence, especially on the closing bossa nova-inflected “Nunca Nunca.” “Don’t Call Me on the Telephone, Baby” is uncomfortably close to Larry Williams’s “Bad Boy” and how the Beatles did that, but nothing else here is as obviously derivative.

Note that “Only in Your Eyes” isn’t the Break It All version, but the much rarer earlier one recorded for a single in March 1965. The complicated origins of the rarities are explained and annotated in Palao’s liner notes.

10. Various Artists, Let’s Stomp!: Merseybeat and Beyond 1962-1969 (Strawberry). As the liners to this three-CD, 93-track collection begin, “Merseybeat was a relatively brief phenomenon—still a local scene in 1962 and fading by the end of 1964.” But did any other such brief boom echo so loud and long in the history of rock? This was the true beginning of a distinctive British rock sound, which would transform not just the country’s music industry, but also music and even youth culture the globe over.

Much of its mammoth influence, of course, was due to the band who wasn’t only the biggest and best on the scene, but also the best rock group of all time. Alas, the Beatles aren’t represented on this compilation for licensing reasons—not even by one of their pre-EMI Hamburg recordings. But virtually everyone else is. While some of the selection can be debated, it’s the most all-encompassing Merseybeat compilation both in its quantity and its range.

All of the non-Beatles hitmakers are here: the Searchers, Gerry & the Pacemakers, Billy J. Kramer, the Swinging Blue Jeans, the Mojos, the Merseybeats, the Merseys, the Fourmost, and Cilla Black. So are the names known who didn’t quite make it big, even if they’re known to many: the Big Three, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, Jackie Lomax, Tommy Quickly, the Remo Four, Tony Jackson post-Searchers. So are plenty of names known only to those who were there or ravenous collectors, like the 23rd Turnoff, Wimple Winch, Jason Eddie, and Ian & the Zodiacs. So are some names that were unfamiliar to this know-it-all reviewer, from Jeannie & the Big Guys to Satin Bells. The only omission I’d argue for is the Pete Best Combo, whose “The Way I Feel About You” is pretty storming garage pop, even if it was recorded in the US.

Every British Invasion collector would have a different selection to propose for such an anthology, and a few acts aren’t heard at their best. Certainly the Merseybeats’ “Our Day Will Come” and Ian & the Zodiacs’ “Beechwood 4-5789” hardly count among their best work, and Gerry & the Pacemakers’ “Slow Down” is a non=starter compared to the Beatles’ version. Like a good number of compilations of this sort, the mix of classic hits (the Swinging Blue Jeans’ “Hippy Hippy Shake,” Kramer’s “Bad to Me,” and the Searchers’ “When You Walk in the Room”) with deep cuts and obscurities means that almost anyone who buys this will already have some (and maybe even much) of it elsewhere.

But heard a few times, this does grow on you for its sheer diversity. There’s certainly Merseybeat in the classic chipper catchy guitar-driven style; the Fourmost’s “I’m in Love,” one of the lesser known Lennon-McCartney songs the Beatles didn’t release, is one of the best such items. But there are plenty of woman solo acts and girl groups, often in a pop or soul style; journeyman club rock’n’roll by some of the Beatles’ peers who never quite made it outside of Liverpool and Hamburg, like King Size Taylor; light psych from Focal Point; mod from the Thoughts (whose “All Night Stand” is featured in its rarer US version, though it’s not much different than the UK one); and demented early freakbeat, though Jason Eddie’s ‘Come On Baby” is pretty well known to devotees of the form.

Listing all the non-hits of high quality (albeit mixed with some mundane efforts and routine covers) would take quite a few paragraphs, but listen especially for Jeannie & the Big Guys’ tough interpretation of Titus Turner’s “Sticks and Stones”; a surprisingly worthwhile run through “Sally Go Round the Roses” by ex-Vernon Girl Lyn Cornell; and the Remo Four’s solid blue-eyed soul/rock take on Gloria Jones’s “Heart Beat.” Although they’ve done the reissue rounds for decades, the bittersweet, ethereal psychedelia of the 23rd Turnoff’s “Michael Angelo” (sic) and Wimple Winch’s mod mini-epic “Rumble on Mersey Square South” are among the very few items here that show local bands innovating with the changing times and more serious, sophisticated compositions. As the Beatles did—and, somehow, their Liverpool peers didn’t, almost without exception.

There are just three previously unreleased tracks, all carrying some degree of interest. The Maracas’ “A Different Drummer” is a Joe Meek production. Samantha Jones’s “This Is the Real Thing” wasn’t on one of her numerous ‘60s singles, and was retrieved from an acetate. Shel Talmy produced the Pathfinders’ moody and well-harmonized “Lonely Room,” the best of this trio of vault finds, is a fine cover of an Ivy League composition.

Is there much more to be found by many of these acts on other compilations, single-artist or various-artist? Sure (though probably not in the Pathfinders’ case), and everyone will have their favorites, sometimes many, that aren’t featured here. For the less fussy who want a good overview of the breadth of ‘60s Merseybeat, however, it works as a starter or sampler, with detailed, bountifully illustrated liner notes by compiler Jon Harrington. (A slightly edited version of this review appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

11. David John & the Mood: Diggin’ for Gold (Cherry Red). David John & the Mood put out only three non-hit singles as part of the mid-1960s British R&B/rock explosion. But they’re pretty fondly regarded by collectors, in part owing to their inclusion on numerous specialist archival compilations. This 22-track anthology is the first actual compilation of material by the group, though it doesn’t actually include much in the way of songs they didn’t release. All six cuts from the 45s are here, but much of the rest are alternate versions and backing tracks. There’s just one song, the outtake “That Little Old Heartbreaker Me,” that wasn’t on the singles in some form. Even that song is presented in three different versions, one of them a backing track with backing (but no lead) vocals.

Although David John & the Mood were a second-tier British R&B/rock outfit, most of the half dozen numbers on their singles were pretty good. When their material first appeared on reissues, there was speculation that “David John” might actually be a pseudonym for David Bowie, as there’s some similarity between how John (given name David John Smith) and very early Bowie sing in a high, sometimes squealy and mannered voice. “I Love to See You Strut” in particular is pretty taut and brash; “Bring It to Jerome” is a good Bo Diddley cover, if not on the same level as the original or Manfred Mann’s version; and “Pretty Thing,” likewise no match for the original or the Pretty Things’ cover, captures the naive energy of the young British R&B acts well, with one of the all-time great weird dissonant sloppy guitar solos of the genre.

On reflection, John doesn’t sound quite as much like early Bowie as sometimes suspected when “Bring It to Jerome” and “I Love to See You Strut” appeared on Pebbles Vol. 6 back at the end of the 1970s. There are hints that he and the Mood could have developed into something more notable and important than a fairly typical, if slightly better than average, early sub-Stones et al. combo. They didn’t get the chance, however, owing to some bad breaks and questionable management, though they were able to record a couple singles with producer Joe Meek.

While I like David John & the Mood, it can be disputed whether they’re worth the kind of treatment the Beach Boys get with their box sets, where many of the selections are backing tracks and not-so-different alternates. The different versions on this comp aren’t notably different than the familiar (at least to the kind of collectors who accumulate this stuff) ones, though an acetate version of “Diggin’ for Gold” isn’t as close as the others. Even most such collectors would be satisfied with an EP or mini-LP of the singles plus the outtake and acetate. This does, however, come with a 20-page booklet with a full history of the group that documents them much better than anything else that’s been published.

12. P.J. Proby, Presley Style: Lost Elvis Songwriter Demos 1961-1963 (Bear Family). P.J. Proby was most known for his brief period of superstardom as an expatriate American singer in Britain in the mid-1960s, though he had only modest success in his native US. In the early 1960s, before he was known for his own records, he recorded numerous demos of songs for Elvis Presley to cut. That’s been known for a long time, but this 21-track collection marks the first release of any of the material. While it’s of more interest as an historical oddity than for its intrinsic merits, it’s not without such merits, if something of a footnote in the careers of both Proby and Presley.

Proby could credibly emulate Elvis’s style, though he had more of a warble and was ultimately no match for Presley’s greatness. Nor were the songs featured on this anthology among Elvis’s best, even by the standards of his Presley’s generally somewhat diminished early-‘60s output. If you’re looking for highlights from the Elvis catalog from this period like “Little Sister” or “Return to Sender,” or even “Just Tell Her Jim Said Hello,” be aware no such items are here. Also be aware that these songs aren’t even among his best or best known secondary early-‘60s output, and were mostly used as filler on his soundtracks, or not even used at all by Elvis. All but three were written by the Sid Wayne-Ben Weisman composing team, hardly the best songwriters of the era, or even among the best who wrote for Presley.

All those reservations out of the way, this isn’t such a bad listen, though it’s uneven and has a few turkeys. Proby undoubtedly attacks the material with professional zeal; the backing, likely by the Wrecking Crew at least some of the time, is like the vocals better than the material; and some of the songs are pretty fair, and occasionally rock out. “Come and Get It,” for instance, is a decent tough bluesy rocker that would have been one of Presley’s better LP tracks had Elvis done a version (he didn’t). “Carnival of Dreams” is a neatly dramatic torch song-cum-rocker. There are also songs neither Proby nor Presley could have done much to elevate, the military ode “Snap To!” being the most flagrant example.

This collection does raise the issue, as does much of Presley’s post=’50s output, of how much he would have benefited from being able to record more songs by writers closer to his age and musical passions by the likes of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller. Or even by using songs from composers with a good rock sensibility who were older than Elvis, like what Doc Pomus wrote with Mort Shuman. The issue isn’t discussed by the thorough liner notes, which treat the material as if it’s of deserving of canonization as anything Presley did. If ultimately something of a curiosity, as such curiosities go, it’s pretty interesting.

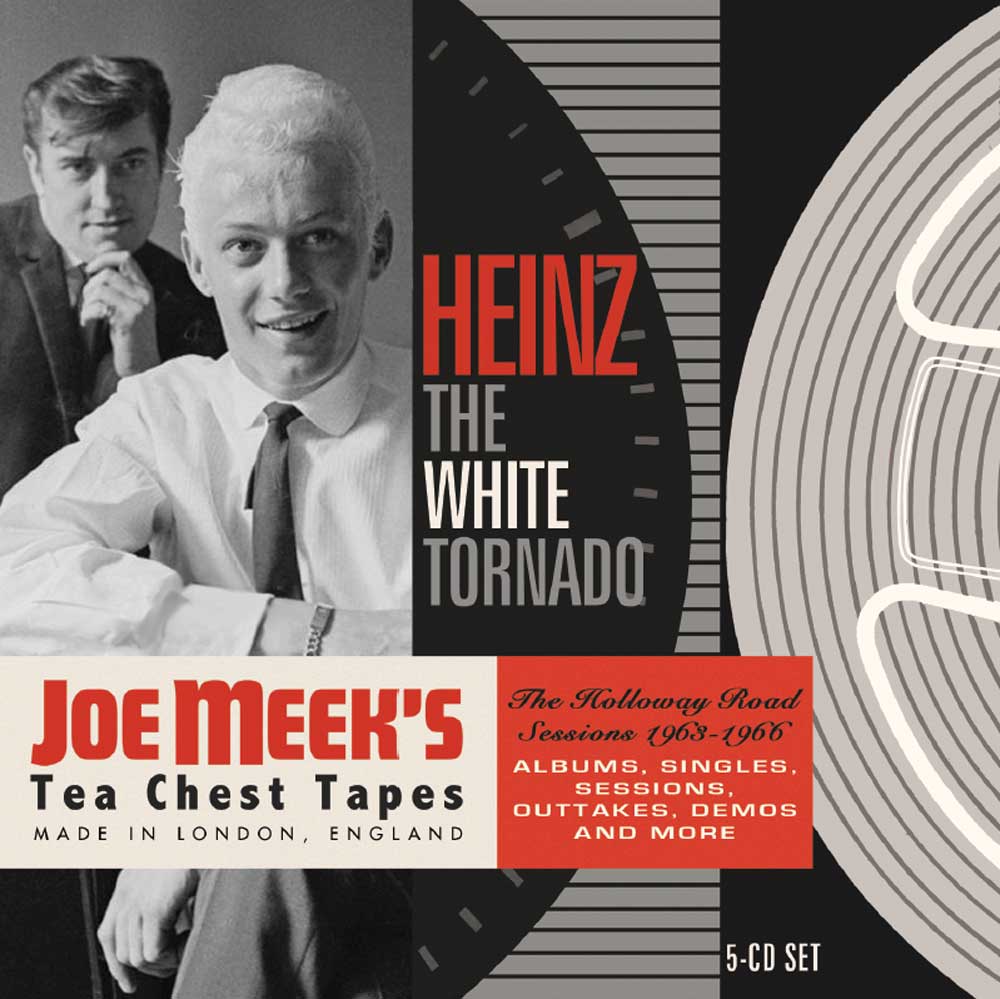

13. Heinz, The White Tornado (Cherry Red). For someone often berated for having little vocal or instrumental talent, and sometimes cast as a stooge of sorts (putting it politely) who never would have gotten on disc if not for the patronage of producer Joe Meek, Heinz sure made a bunch of good records. It’s true they might have owed more to stellar backup musicians and Meek’s production than Heinz’s limited skills. But “Just Like Eddie” (his sole big UK hit), “Big Fat Spider,” “Movin’ In,” “I’m Not a Bad Guy,” “Hush-A Bye Baby,” and “That Lucky Old Sun”—to name just a few—are certainly dynamic, highly enjoyable sides in an Meek-meets-the-British Beat explosion way. How much Heinz, however, is too much Heinz?

This five-CD box certainly begs the question, even for Heinz/Meek fans. With the accent on demos and alternate takes found in Meek’s seemingly bottomless “tea chest tapes,” there’s certainly insight to be heard into how the tracks were generated and polished. Many of them, however, can’t help but expose the weaker (and sometimes weakest) elements of Heinz’s voice, and the sometimes undistinguished and/or corny material, before they were burnished by Meek and company. And while almost all of his 1963-66 releases are represented by the original versions or versions that are close to what was issued at the time, there are few songs that weren’t on those discs.

I am a Heinz fan, at least of most of his singles and some of the tracks from his sole LP. But let’s be realistic—his demos, backing tracks, and alternate takes don’t carry anything like the charge, let alone historical importance, of the kind of similar marginalia that fills up box sets of the likes of the Beatles and the Beach Boys. It can be tough to wade through slightly different or meager outtakes by those groups too, but at least they nearly always illuminate the creative process of some of the greatest artists of the twentieth century. For all his attributes, Heinz wasn’t one, and for all his erratic studio genius, Meek wasn’t on that level either.

For most fans, a selective compilation, or even the uneven double CD Just Like Eddie: The Heinz Anthology (which has all his 1963-66 tracks), is far preferable to this far scrappier if far more extensive overview. Even serious Heinz fans—and it’s hard to imagine many who get this set won’t already have his standard output—might have been better served by a much more selective trawl through his extras. Some of the alternates are simply the official versions at the original speed, and while the revelations that Meek often sped up the recordings for release are interesting, the slower-running variations aren’t better. The annotation could have been clearer about who’s singing what—it’s usually Heinz, but Meek himself (who was a woeful singer) and songwriter Geoff Goddard are also heard on vocals at some points.

It’s not often that the less familiar material on this box will perk up your ears, whether because it’s different from what you’re used to or it’s pretty good. But there are some tracks that do strike such chords. A demo of “Heart Full of Sorrow” is slower and gutsier than the single, missing the chirpy female backup vocals; a “Big Fat Spider” demo, though missing the incredible creepy guitar licks of the 45, has a notably different bouncy feel and prominent organ; take 7 of “Movin’ In” isn’t much different from the single, but has stunning guitar work, also demonstrating that Heinz could summon satisfyingly raw vocals once in a while.

There are a bit more than half a dozen songs that didn’t make it beyond the demo/outtake stage, including a rudimentary cover of “Fever.” Most of the others are poppy trifles, some of them bearing an “unknown” songwriting credit. But even these can’t be wholly written off, the box ending on its highest note with “Voices On the Wind.”

As haunting as all but the best Meek compositions and productions—and Joe had many of those—this spare yet effective performance has a decent Heinz vocal and is utterly devoid of the frivolity found in many of his (and Meek’s) other efforts. Although the ending refrain goes on for too long, this stately and somber number is easily up the standard of Heinz and Meek’s better tracks. It reminds us why many listeners still care about their work sixty or so years later, even if they have to be very dedicated to their legacy to spring for this box’s super-deep survey. (A slightly edited version of this review appeared in Ugly Things magazine.)

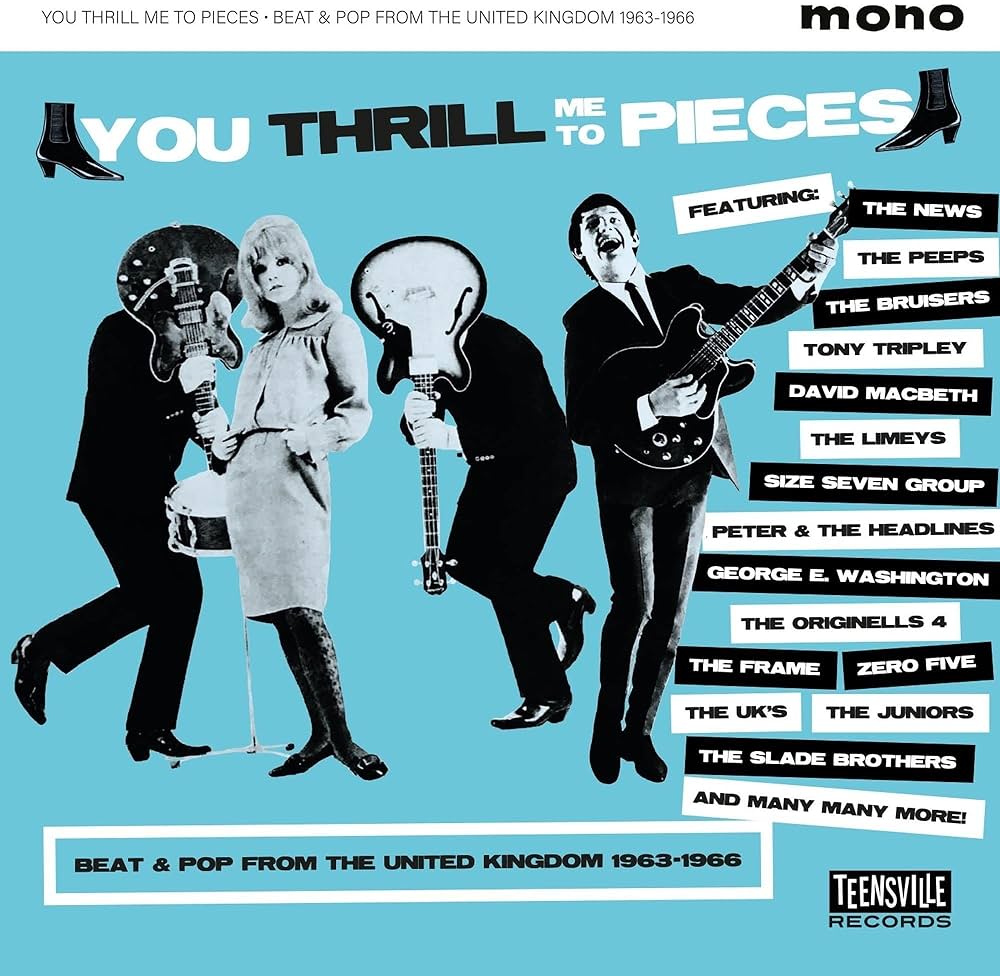

14. Various Artists, You Thrill Me to Pieces: Beat & Pop from the United Kingdom 1963-1966 (Teensville). This has an even more tenuous spot on a best-of list than the Heinz box above. And like that Heinz box, it’s only on here because it’s in a genre in which I specialize – perhaps the genre (mid-‘60s British rock) in which I specialize more than any other. None of these 34 tracks were close to hits, and in fact few of the groups are at all recognizable even to most British Invasion collectors, except the Merseybeats (represented by a demo, “Janie, I Love You,” that might be rare, but isn’t very good). Some of the musicians achieved greater subsequent fame in other contexts, most blatantly Mick Taylor, whose early combo the Juniors weighs in with a forgettable 1964 single. There are some other famous associations in the Echoes, who were Dusty Springfield’s backup group, and the Cockneys, whose Mick Grace filled in for an ill Ray Davies on a brief mid-‘60s European Kinks tour. But for the most part these musicians made little impact at any time.

In its favor, unlike many similar compilations, this doesn’t have lame covers of American rock and soul songs. It’s wholly comprised of compositions you don’t come across anywhere else, many written by the acts themselves, and some that might be by famous songwriters (Goffin-King, Clint Ballard Jr., Les Reed-Barry Mason, Roger Greenaway) but are utterly unfamiliar. It’s far more pop-rock (and sometimes more pop than rock) than R&B, and there’s nothing by the kind of obscure bluesy mid-‘60s UK acts that made good rare discs, like the Fairies, the Birds, and the Wheels. Merseybeat might be the biggest influence, but generally these acts and their writers/producers/labels were trying to make catchy hits.

To be cold, most of them aren’t that catchy, though enough of them are pleasant to be modestly enjoyable while they play, even if they don’t stick with you. It’s a testament to just how prolific the British scene was at the time. But it does make you wonder whether the labels—and there were only a few big ones in the UK, who dominated the business, and were responsible for every one of these 34 tracks—were that wise in giving so many acts a chance. Even at the time, it seems like most of these would have been given little chance at being hits by either average listeners or the record companies, or sometimes even by the performers.

Two of these tracks – not a high percentage, admittedly – do stand out in this crowd, and to my knowledge have never previously been issued on CD. One is the most famous, the Cockneys’ Mick Grace-penned “After Tomorrow,” to which they mimed in the opening sequence to the quickie British rock movie Swinging UK in 1964. Not that it’s brilliant, but it has the kind of quirky unpredictable chord changes, mix of major and minor melody, and exuberant harmonies found in the better Merseybeat (although they were from London). Another is “Kiss Me” by the Viscounts, most remembered (if at all) for Gordon Mills—later manager of Tom Jones, Engelbert Humperdinck, and Gilbert O’Sullivan—being a member. Although it’s kind of corny and diluted a bit by orchestration, it does have the sort of catchy Merseyish melodies and all-out chipper harmonies that had genuine hit potential. As another testament to the imperfection of the British record business, it was used as a B-side, and to my knowledge has never been reissued before this compilation.

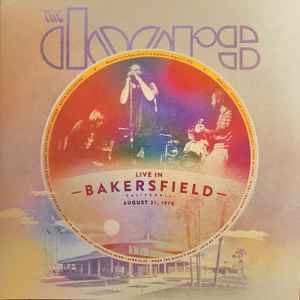

15. The Doors, Live in Bakersfield, August 21, 1970 (Rhino). Should this be the only live Doors release in existence, it would rate much higher on this list, as their box of 1967 Matrix tapes does. It isn’t, of course; besides the double Absolutely Live album they put out back in 1970, there are many posthumous concert discs, with more than a dozen discs of material from 1970 alone. This double CD isn’t too much different from those, while the sound, from a two-track tape on a reel-to-reel recorder by road manager Vince Treanor, isn’t quite as good as the others, though it’s alright. It’s also the last of the Doors concerts that was recorded to make it to official release, with the exception of their Isle of Wight appearance from only about a week later.

The Doors were sticking to pretty similar set lists during this time, and my heart did not race at the prospect of yet another medley of “Alabama Song/Back Door Man/Five to One.” Still, this Record Store Day release (on both LP and CD) – not too hard to get on CD a few weeks later, despite its limited-edition status – has its merits. More often than you’d expect, the Doors sort of clowned around and didn’t always seem to take their songs too seriously in the later concerts they did with Morrison. There’s none of that here, the band playing things fairly straight, and with a lot of commitment, even if they might have done “When the Music’s Over,” “Roadhouse Blues,” “The End,” and the medley many, many times by this point.

Less traveled tunes like “Universal Mind” (combined with parts of Mongo Santamaria’s “Afro Blue”)” and “Ship of Fools” are also included, along with a medley of “Mystery Train/Away in India/Crossroads” that might strike some beginning Doors fans as out of the blue, but which they did at a number of other concerts from this time that have come out. Most exciting is a nine-minute “Love Me Two Times,” both because there aren’t many live versions of that around, and because it’s a lot more stretched-out than the familiar, much shorter hit single, even detouring into “Baby Please Don’t Go” and “St. James Infirmary.”

It’s unfortunate that Treanor’s tape ran out after ninety minutes, leaving some of the two-hour-plus show undocumented (and also missing the first few bars of “Roadhouse Blues”). Maybe that had some other less run-of-the-mill tunes. What’s here has some interesting improvisations, and although it’s sometimes reported that the band and particularly Morrison were losing some heart at this point, they’re giving it their all, with some especially intense screams and crescendos on “The End.”

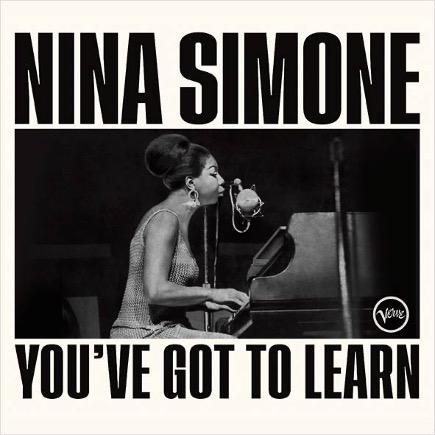

16. Nina Simone, You’ve Got to Learn (Verve/Universal). More Nina Simone from the 1960s is always welcome, though this live July 2, 1966 performance at the Newport Jazz Festival is rather peripheral to her large discography. At about 33 minutes, it’s pretty short, and note that while there are seven tracks listed, one is a forty-second spoken “Intro to Blues for Mama.” The sound and performance are very good, but the song selection is a little on the sedate side, particularly with “I Loves You Porgy” and the ballad “Music for Lovers.” Better and more forceful, though not scintillating, are Charles Aznavour’s “You’ve Got to Learn,” the Simone-Abbey Lincoln co-write “Blues for Mama,” and the highly percussive quasi-spiritual “Be My Husband.” The highlight is a “Mississippi Goddam” that’s taken at a more relaxed funkier pace than the more familiar frenetic versions. It’s not as good as that faster version, but at least it’s notably different. Even within just six songs, this testifies to the unpredictably wide eclecticism of her repertoire, though it doesn’t match the highlights of her recorded work in the era.

17. Jimi Hendrix, Hollywood Bowl August 18, 1967 (Legacy). This was one of the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s first shows in the US, after their triumphant appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival and concerts at the Fillmore, but also after their disastrous, aborted time as an opening act on a Monkees tour. They were still an opening act (for the Mamas and the Papas) at this Hollywood Bowl gig, a week before the US release of Are You Experienced. Recorded by a radio station technician, the sound is good, and the audience reaction somewhere between what you’d imagine the feedback to have been at their previous Californian shows and the Monkees concerts. In a way that helps, since there’s little audience noise to compete with the music. On the other hand, Hendrix sounds a little displeased by the indifferent crowd, judging from between-song remarks like “thanks anyway” after “Killing Floor” and a promise to do a song “from the bottom of our hearts” before “Like a Rolling Stone.” “We’d like to dedicate this last number to ourselves,” he says before “Wild Thing.” “Well, might as well, there’s nobody else here.” Noel Redding even handles a few of the announcements.

As for the performance, it’s pretty good, but at this point not a standout in the bulging Hendrix catalog of posthumously released live shows. It’s similar to their long-available Monterey set, but not as fine. Jimi forgets a few words during “The Wind Cries Mary,” and the interplay between him and the backup vocals on “Fire” is kind of sloppy, though there aren’t other notable flaws. The set does include a few songs that weren’t available on early Hendrix discs, notably “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” “Catfish Blues,” and a couple covers he had performed at Monterey, “Killing Floor” and “Like a Rolling Stone.”

18. Jackie DeShannon, The Sherry Lee Show (Sundazed). Here’s another one for the “primarily of historical interest” pile, although the music is of solidly respectable quality, if hardly nearly as good or characteristic of what the artist would do at her best. It’s amazing enough that these were found and preserved, as this presents 31 songs DeShannon sang on an Aurora, Illinois radio show in 1956 and 1957. She was only in her early teens, and going by the name Sherry Lee. She didn’t sound too much like she’d sound when she started to make many, and often very good, recordings in the early 1960s as a pop-rock singer, often writing her material. Instead, she sounds like a young early honky-tonk performer, with country her main influence, though there’s some early rock and roll in the mix.

These tapes—in decent, though not studio, quality—are somewhat like the early (mid-1950s) country efforts of Wanda Jackson, or the earliest singles by Patsy Cline. DeShannon rocks a little harder than Jackson or Cline did on those discs, but nothing is nearly as hot as Jackson’s early rockabilly classics, and she’s not as deep in the country bag as Cline (whose “Walkin’ After Midnight” she covers here). Most of the cuts are fair honky-tonk tunes, and while DeShannon’s vocals are strong for a youngster, they lack the personality she’d stamp many of her cuts with in the 1960s, almost to the point where she sounds like an entirely different artist here. About the only thing that does separate her somewhat from other early honky-tonkers are some ventures into Elvis Presley and Fats Domino songs, though they way they’re arranged here is more on the country side of things than rock’n’roll. It sure sounds, by the way, like she sings about catching someone in bed (rather than dead) in her version of “Baby Let’s Play House,” on which she doesn’t bother to change the subject from a girl.

Once in a while on my lists, I note a release from a couple years back that I somehow missed at the time. Here’s one for this list, though it came out in 2021:

Laura Nyro, Go Find the Moon: The Audition Tape (Omnivore). This is really more an EP than an album, the eight tracks lasting a mere eighteen-and-a-half minutes, including some incomplete fragments, studio talk, and a false start. This previously unreleased 1966 tape is – the phrase must be again used — primarily of historical interest, even for Nyro fans, due to its brevity and far barer arrangements than even her first album would boast. There aren’t really arrangements, actually; it’s just her on solo piano, going through a few songs that would appear on her early albums (“And When I Die,” “Lazy Susan,” and “Luckie”), and three that didn’t make any of her records (“Go Find the Moon,” “Enough of Your,” and “In and Out”). It’s not fair to judge a solo audition tape against a fully arranged studio album, but like other such demos, it illustrates how much the songs benefited from full backup, as they did on Nyro’s debut More Than a New Discovery.

Her talents as a songwriter, and also (though they generally haven’t gotten as much acclaim) singer and pianist, are evident, particularly on the song that’s by far the most famous, “And When I Die.” The others, including the previously unheard compositions, aren’t as striking, though they show her knack for blending soul, pop, Tin Pan Alley, and gospel was already developed, and her vocals fully mature. The producers (Artie Mogull and Milt Okun) deserve some credit for detecting her big potential, although the solo piano backing makes much of the material rather similar sounding. Asked if she can play some songs that she didn’t write, Nyro seems rather stuck for a musical response, going through a partial version of “Kansas City” and just a few lines of “I Only Want to Be With You.” Whether or not she knew other people’s songs by heart, maybe she was reluctant to do any but her own at this audition, although ironically, she’d do the best all-cover album by a noted singer-songwriter a few years later on 1971’s Gonna Take a Miracle.