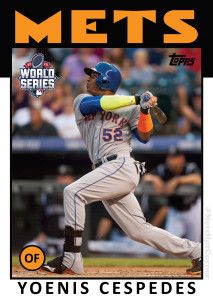

For a few weeks last year, Yoenis Cespedes was being touted as a credible National League MVP candidate. He hadn’t played with the New York Mets much more than a few weeks after getting traded from Detroit at the end of July. But he was in the midst of a ridiculously hot streak, and the rationale was that the Mets wouldn’t be where they were without him. He cooled off some near the end of the season, and so did talk of Yoenis for MVP, Cespedes (who had 17 home runs and a .942 OPS in 57 games) finishing 13th in the voting with 24 points.

It struck me as kind of ridiculous that any player could be considered for MVP on the basis of just a few great weeks, or indeed on less than a whole season. I hoped to post about this at the time, but I didn’t have time at the time, and by the time I had time, the season was over. Spring training for 2016 has just started, however, and now’s the time to blog about it, as belated as it is.

No one’s won an MVP for his work on a team for whom he didn’t play the entire season, and no one’s won an MVP who has missed as much as a third of the year (though some MVPs have missed signficant time, as George Brett did in 1980, when he hit .390 in 117 games). During the brief Cespedes-for-MVP campaign, I became curious as to how many players with similar partial seasons attracted MVP votes. I knew there were some, but a little to my surprise, there were quite a few, and not all from the distant past, when the ever-debatable notions as to what constitutes an MVP weren’t as solidified. There are too many, indeed, to list in a blog like this without going into several thousand words. So this is a survey of some of the more credible or interesting half or partial season would-be MVPs.

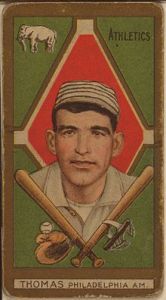

Candidates in this category factored into the MVP voting from the very beginning of the award, or any rate its predecessor, the Chalmers Award (only given from 1911 to 1915). In 1911, A’s catcher Ira Thomas finished eighth in the AL MVP voting despite only playing 103 games with 337 plate appearances, and batting a respectable but hardly notable .273 in the dead-ball era. Catchers with modest (and sometimes, as in the case of Al Lopez, even poor) batting stats in general fared much better in the early years of MVP voting than they would in more recent times, perhaps being viewed as team leaders or semi-managers at a time when there were far less coaches. In 1913, A’s catcher Wally Schang finished tenth despite playing just 79 games with 252 plate appearances, and an okay but not-too-threatening batting line.

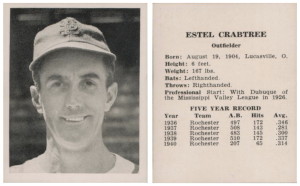

Even putting catchers aside, some of the players getting stray votes in early MVP contests were strange, even indefensibly weird choices — anomalies that occur throughout the history of MVP voting, if less frequently now than then. In 1925, Boston second baseman Doc Gautreau got a couple votes for NL MVP despite playing just 68 games and notching a decidedly unimpressive .676 OPS. (Listed at just five-foot four and 129 pounds, he must have been one of the smallest players of an era.) In the 1930s and early 1940s, a few part-time players with what would now be called “outlier” seasons got down-ballot votes, like A’s catcher Earle Brucker did by batting .374 in 53 games in 1937, and Cardinals reserve outfielder Estel Crabtree did in 1941 by hitting .341 (at the age of 37, after an eight-year absence from the majors) in 198 plate appearances. Senators backup outfielder Dave Harris got five points in 1932 despite just 177 plate appearances, though he did hit well in those, with a .938 OPS.

As the back of his baseball card made clear, Estel Crabtree spent years in the minors before getting called back up for his breakthrough 1941 season.

The most credible part-time MVP candidates emerged during World War II, when many players were in the military for entire seasons or parts of season, affecting both the quality and predictability of major league ball for a few years. In 1943, the first of the three years in which many players were in the military (though some had entered with increasing numbers in 1941 and 1942), Bill Dickey finished eighth with 85 games and 284 plate appearances. He did have a very good year for the pennant-winning Yankees, hitting .351 at a time when offense was depressed by a less lively ball. (In 1938, fellow Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett finished tenth in the NL with just a bit more playing time, his cause no doubt helped by managing the pennant-winning Cubs as well.)

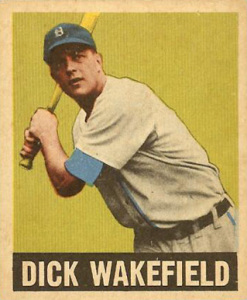

In 1944, for the first time, a non-catching half-timer was a serious MVP threat. Detroit Tigers outfielder Dick Wakefield, who’d finished sixth in his 1943 rookie year, finished fifth despite playing just half a season. In that half season, he was spectacular, hitting .355 with power for a 1.040 OPS. Had he played the whole year, there’s little doubt the Tigers would have won the AL pennant instead of finishing just a game behind the St. Louis Browns (who won their only pennant that year). Of course, all times were missing key players in those years, and many would have won significantly more or less games had the war not been raging.

When you look at Wakefield’s record, you’d logically assume he had to miss the second half of the season, almost all players who missed partial years being called up after play had begun. Oddly, he missed the first half of the year and played the second. He was in the Navy, but was discharged when his aviation program was discontinued, though he was called up again at the end of 1944 and missed 1945. Though he looked like he’d be a superstar, Wakefield, like some other players who had great years during the war, didn’t come close to matching his previous stats after 1945, and was just a journeyman after the war.

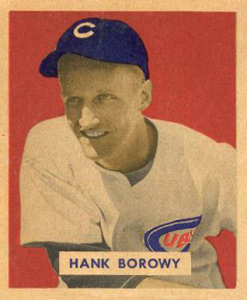

In 1945, there were strong part-season MVP candidates in each league. Pitcher Hank Borowy was famously sold to the Chicago Cubs for $100,000 after clearing waivers in the American League, despite having a 10-5 record. With the Cubs, he was great, going 11-2 with a 2.13 ERA and basically providing the difference that gave them a slight edge over the Cardinals and put them into (as of this writing, their most recent) World Series. Borowy was sixth in the MVP voting, and although a couple Yankees rookies (Tiny Bonham in 1940 and Whitey Ford in 1950) got a few votes for spectacular debut years in which they had just a dozen starts, there would be just a couple subsequent occasions on which such pitchers would figure strongly in MVP contests.

There’s still uncertainty and controversy over how Borowy managed to clear waivers, and why the Yankees let him go. The Yankees claimed he’d become ineffective, though his good (if not quite great) performance with them in 1945 indicates otherwise. It’s been speculated that the Yankees really wanted the $100,000 more than they wanted to get rid of Borowy, and that the other American League clubs didn’t claim him on waivers (necessary to enable his sale to an NL club) because they figured the Yankees would withdraw him from being available if that happened. A la Dick Wakefield, Borowy had just a brief and so-so career in the years after the war ended.

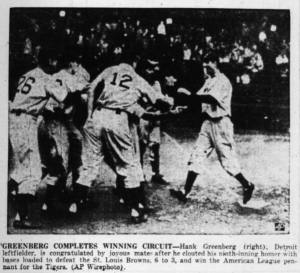

Also in 1945, the Detroit Tigers had one of the most serious half-season MVP candidates in baseball history, though he oddly underperformed in the voting itself. Superstar slugger Hank Greenberg spent most of 1941 and all of 1942-44 in the military, getting out in time to play the second half of 1945 with the Detroit Tigers. In that half year he hit .311 with power at a time when, again, offense was way down because of a less lively ball. Had he doubled his stats, he would have won the Triple Crown. He also hit the game-ending (actually season-ending), come-from-behind grand slam that clinched the pennant for the Tigers in their last game (though they would have been able to play one more game to clinch the pennant had they lost). The Tigers certainly wouldn’t have gone to the World Series (which they won, over Hank Borowy’s Cubs) had Greenberg not returned for the final half of the schedule.

Yet Greenberg was just 14th in the MVP balloting. #1, deservedly so, was another Tiger, pitcher Hal Newhouser, who won 25 games. It’s strange, though, that average-hitting, not-quite-full-time (83 games) Tiger catcher Paul Richards finished tenth, ahead of Greenberg. Indians shortstop Lou Boudreau was limited to 97 games, but finished eighth. Maybe Greenberg was unpopular with some writers; maybe there were too many other Tigers getting votes; or maybe they figured he’d already won a couple MVPs (in 1935 and 1940). Greenberg probably wasn’t too hurt, as he was able to play for a World Series winner.

“That was the biggest thrill of all,” Greenberg later said of his pennant-winning homer, hit shortly before darkness would have ended the game on a rain-sodden field. “What was going through my mind is that only a few months before I was in India, wondering if the war would ever end. Now I had just hit a pennant-winning grand-slam home run. I wasn’t sure whether I was awake or dreaming.”

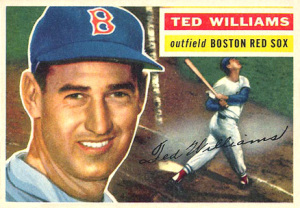

Another great slugger of the era had a great half season in a close pennant race a few years later. Joe DiMaggio was out with an injury for the first half of 1949, but came back with a .346 average, 14 homers, 67 RBI, and a 1.055 in the second half. The Yankees beat the Red Sox by just a game, and certainly wouldn’t have gone to the World Series if DiMaggio had played significantly less than what he managed. Of course, had DiMag not been injured for such a long time, likely the pennant race wouldn’t have been as close as it was. But even if you doubled Joe’s stats, they wouldn’t have matched those of the MVP and Triple Crown winner Ted Williams. DiMaggio finished only twelfth in the voting, behind four of his own teammates.

A few years later, Williams became the only position player to get an MVP vote with less than 100 at-bats. Serving in Korea for much of 1953, he was able to play in 37 games near the end of the year, and had the best season — easily — of any player in history with less than 100 AB, hitting .407 with 13 homers and 34 RBI in 91 at-bats for an astronomical 1.410 OPS. The greatest month in history can’t win you an MVP award if you don’t play much of the rest of the year, though, and he just got one point, perhaps from a sympathetic journalist who recognized Ted’s sacrifice in going into the military for a second stint (he’d also served in 1943-45). Less well known is that in the previous year, Monte Irvin got five points despite only getting 126 at-bats due to a broken leg, again perhaps from a journalist who sympathized with a bad break.

In 1955, Williams became the first position player missing more than a third of his team’s games to place in the top five vote-getters for the MVP award. Playing 98 games, he finished fourth. It was a testament to how good he was in those games — he hit .356 with a 1.200 OPS. He didn’t play the whole year as he didn’t sign a contract until May 13, and didn’t play his first game until May 28. He’d briefly retired, though according to the Society for American Baseball Research’s online Williams bio, “it seemed as though retirement was a strategic move in a divorce.” Finishing fifth, right behind Williams, in the MVP voting was Mickey Mantle, who really should have won that year, as he played 147 games and easily had the best WAR (wins above replacement) mark in the league at 9.5 (Williams had 6.9).

Ballot placings by part-timers became more infrequent in the next three decades, though there were still oddities like votes for spare outfielders/pinch-hitters Dusty Rhodes and Jerry Lynch, and 16 points for Wes Covington when he had a fine 90-game season (.330, 24 home runs) in 1958. Although he managed to play exactly two-thirds of the 162-game schedule, mention should be made of Elston Howard’s seven points in 1967, when he began the year with the Yankees before joining the Red Sox. Howard, a fine player for many seasons, was terrible at the plate that year, hitting .178 with a .478 OPS. The vote was probably in the recognition of stability he brought to the pennant-winning Red Sox’s catching position and his veteran leadership, but that kind of hitting really shouldn’t be recognized in MVP balloting under any circumstances. And he was even worse with the Sox than the Yanks, hitting .147 in 116 at-bats (and getting just two hits, both singles, in 18 World Series at-bats, though post-season performances aren’t considered as part of the MVP voting).

In 1984, Rick Sutcliffe became the only starting pitcher to both seriously contend for an MVP award and not even qualify for the ERA title. After coming over from the Cleveland Indians (where he was 4-5 with a 5.15 ERA), Sutcliffe was sensational in 20 starts for the Cubs, where he was 16-1. That put him at a quite respectable fourth place (and 151 points) in the MVP contest, though teammate Ryne Sandberg won the award. Sutcliffe did win the NL Cy Young, and remains the only Cy Young winner who split the year between two different leagues.

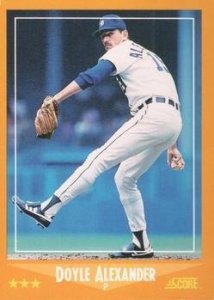

Just three years later, Doyle Alexander finished 13th in the American League MVP voting on the basis of going 9-0 with the Detroit Tigers after coming over from the Atlanta Braves (where he was mediocre, with a 5-10 record and 4.13 ERA). As great as his eleven starts (with a 1.53 ERA) with the Tigers were, they probably weren’t enough to justify any MVP votes, or Cy Young votes, though he did even better there, finishing fourth. It wouldn’t be the last time a pitcher got some MVP votes for a strong finish after getting traded, Randy Johnson picking up a couple points for his 10-1 charge with the Astros in 1998, and another ace ranking much higher with a similar situation in the twenty-first century (see a few paragraphs down).

In 1997, Mark McGwire split his year between the A’s and Cardinals, leading the majors with 58 homers, 24 for the Cardinals in 51 games — which was enough to get him six MVP points, although he got none in the American League, where he’d hit just as well for the A’s in about twice as much playing time. Interleague trades can still result in votes for few games played, Mark Teixeira getting a point for a sizzling third of a season with the Angles in 2008. That was the year not one but two players finished in the top six of the NL voting with portions of full seasons.

The fourth-place player was Manny Ramirez, who had an amazing 53 games with the Dodgers, hitting .396 with 17 homers and a 1.232 OPS. That blaze of glory has since been diminished by PED use revelations. Not far behind him, in sixth place, was C.C. Sabathia, 11-2 with a 1.65 ERA in 17 starts for the Brewers after a so-so 18 starts for the Indians. Unlike Sutcliffe, Sabathia didn’t fare much better in the Cy Young sweepstakes, where he finished fifth. This was less than ten years ago, and while Yoenis Cespedes, to bring us back to where we started, wasn’t quite as phenomenal as Ramirez and Sabathia were over similar part-seasons, they did establish part of the precedent for taking Cespedes seriously as an MVP candidate. So, in a different and lesser way, was another Ramirez, Hanley Ramirez, who was eighth in the 2013 voting despite playing just more than half (86) of the games for his team, the Dodgers, hitting .345 with 20 homers.

Is any player worthy of a first-place MVP ballot who plays less than two-thirds of a season for his team, let alone just one-third of a season, as Cespedes did? No, I would contend. But contending teams will continue to land players like Cespedes near the trading deadline, and they’ll continue to get MVP votes if they get hot at the right time.