How do you put together an ideal version of an expanded edition of an album? No one’s really done it, if that means including every last damn thing available, and somehow making the whole thing a great listen end-to-end, without cuts that are primarily of historical interest. I detailed some of my favorite expanded editions in my previous post.

It’s easier, it seems, to pinpoint what you shouldn’t do on an expanded edition, because so many of them are flawed, in quite a few different ways. Examples could fill up a lot of posts, especially if you included records whose actual core albums I don’t care about a lot. I’m noting a few here by way of illustration, but they have plenty of company.

Combine the classic album with a recent re-recording of the same material. Fans really do want to hear bonus music from the same era in which the core album was recorded, not remakes done years (sometimes many years) later. Case in point: the two-CD expanded edition of Patti Smith’s Horses had a bonus disc of a live performance of the album from 2005 (with a cover of “My Generation” thrown in at the end), thirty years after the original LP came out. (We’re not even getting into the many expanded editions that mostly feature material from the era, but add on just a few recent recordings or re-recordings of little interest.)

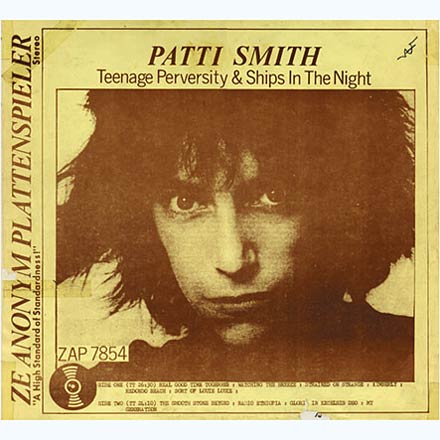

It’s all the more galling considering that one of the best bootlegs of all time—her live concert at the Roxy in Los Angeles on January 30, 1976, which has long been available unofficially (most famously under the title Teenage Perversity and Ships in the Night)—would have made a much more exciting and suitable companion disc. Fidelity isn’t a roadblock; it was broadcast on FM radio, part of the reason it made the bootleg rounds so extensively and quickly in the first place.

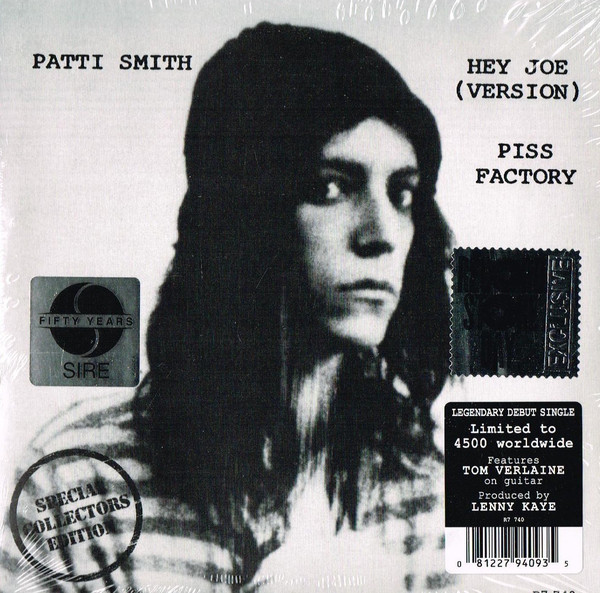

A previous expanded edition of Horses was about as meager as it gets, adding just one track, a live version of “My Generation” from 1976 (recorded just a few days before the Roxy broadcast, which also included “My Generation”). Maybe her pre-Horses single, “Hey Joe”/“Piss Factory,” is unavailable for contractual reasons, but that would also seem like a logical addition to such an edition.

Keep expanding your expanded edition — putting out not just two expanded editions, but even three. Hardcore fans are the lifeblood of the catalog part of the music industry, and the foundation of a legacy act’s base, especially if they’re continuing to tour. It was already a lot to ask of them to buy the classic albums they already owned again at the dawn of the CD era, the rationale being improved sound quality and durability (though those benefits have been questioned).

It’s yet more to ask of them to buy another CD with the same music they already now own on compact disc, with some extra material. It’s quite a bit more to ask them to buy a CD based around the album a third time, and verging on an insult when the expanded-plus-one (or two) edition doesn’t come out long after the previous one.

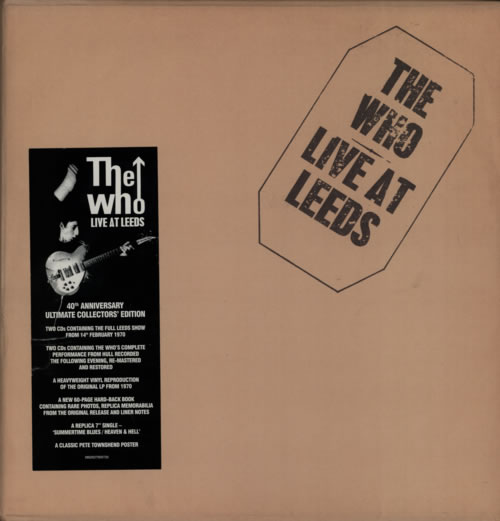

This has happened quite often in the reissue world, but here are a couple illustrations. The Who’s Live at Leeds came out with eight bonus tracks in 1995, pushing the running time to 77 minutes, almost as much as a single CD can fit. That seemed like a good deal, but then it was superseded by a two-CD edition in 2001 that also included a whole disc of Tommy songs from the same show. And then almost ten years later, the fortieth anniversary edition blew it up to four discs, adding their show from Hull the following evening (February 15, 1970). And hey, the 2014 deluxe edition digital release has some additional dialog between songs, as well as longer versions of some of the songs themselves.

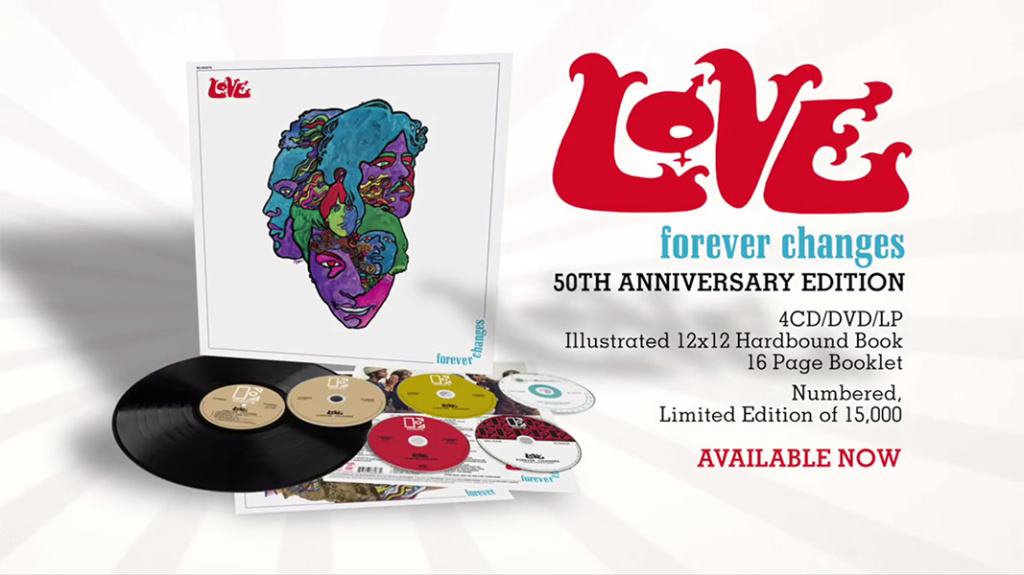

It could be argued that the Who and their label(s) were to some degree responding to a changing marketplace that both made bigger editions more viable, and also made them more necessary as the reservoir of vault material as a whole sank lower. Love’s Forever Changes, however, has been through multiple editions that, unlike Live at Leeds, don’t add nearly as much additional material as the years go on.

The 2001 edition added seven bonus tracks—none of them exactly revelatory, devoted to a non-LP single not on par with the album and some outtakes/alternates that weren’t too notable. Still, good to have if you’re a fan. But if you wanted everything good to have, you also had to get the two-CD “Collector’s Edition” in 2008, with an “alternate mix” of the album and yet more outtakes/alternates/etc.

Then in 2018, there was a four-CD edition, adding a vinyl LP of the Forever Changes album and a DVD with a hi-end audio version (plus just one actual video clip). Such multi-disc and multi-format combinations are themselves becoming more common in the age of spruced-up expandeds. As for the actual music not found on other editions, this adds relatively little, as three of the four discs are variations of the core album (the stereo, the mono, and, much less usefully, an “alternate mix”). The disc of actual outtakes/demos/non-LP sides has just a bit not on previous editions—a couple barely different 45 versions, and a couple backing tracks.

Yes, it does come with a nice LP-sized booklet of liner notes, with plenty of cool illustrations. But more than most productions of this sort, it did seem to mark a point where even some hardcore fans said “enough,” and did not buy this pretty expensive edition, to quote a Bob Dylan song title, the “Fourth Time Around.”

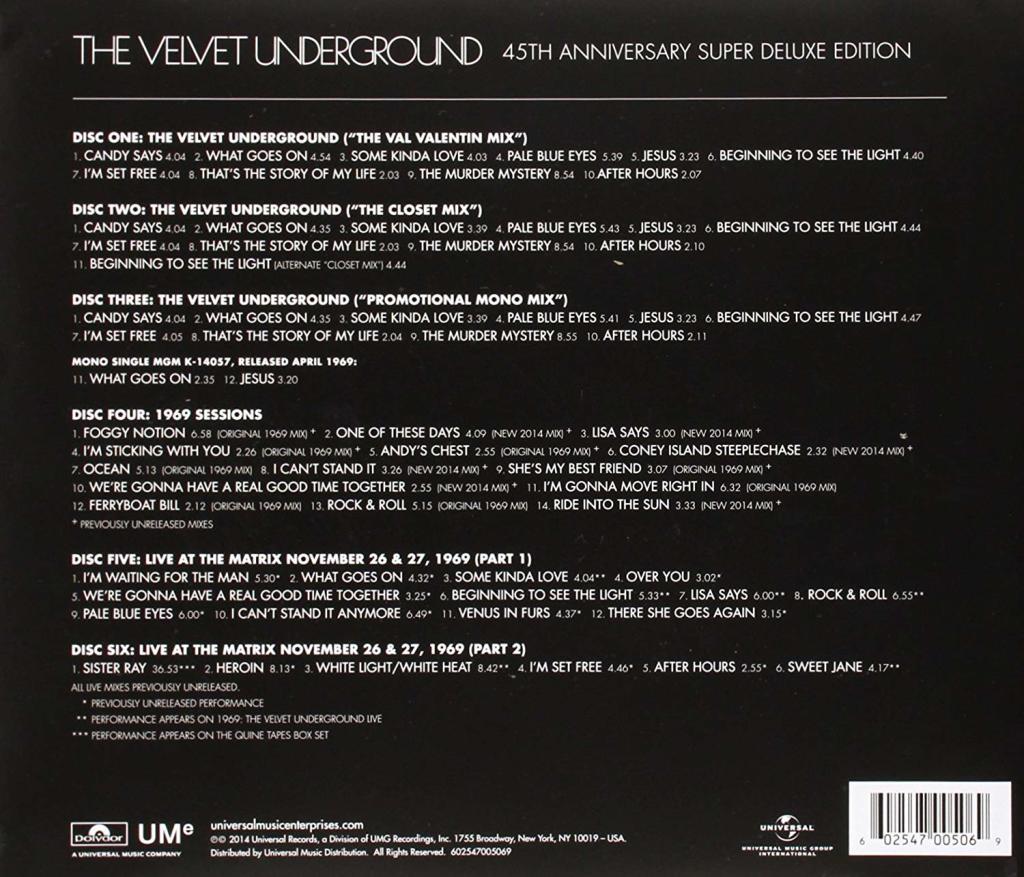

At least these series of Who and Love editions were spread out over a few years. In late 2014, the six-CD super deluxe of the Velvet Underground’s self-titled third album had eleven previously unreleased performances from late 1969 at San Francisco’s Matrix Club, tapes from which had provided the bulk of their classic 1969 Velvet Underground Live double LP. Other previously released Matrix tapes filled out discs five and six of that set. Just a year later, however, the four-CD box The Complete Matrix Tapes made that unreleased material redundant, as it included all of those unreleased cuts.

As I wrote in the expanded ebook edition of my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day, “Considering that serious Velvet Underground fans – i.e., almost anyone likely to buy this super deluxe edition – would also want The Complete Matrix Tapes, this [the six-CD expanded The Velvet Underground] really should have been a four-CD set without any Matrix tapes, holding the eleven unissued tracks for the forthcoming Matrix Tapes box. As it is, many purchasers of this large and expensive box are now likely to have well over half of its contents elsewhere – a slap in the face to the very Velvet Underground fanatics that have made exploitation of their catalog possible.”

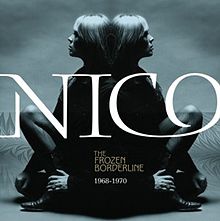

Put out different expanded editions that for the most part feature the same material, but leave something off that’s on the other. There are many such items, even including one I praised in my earlier post about good expanded editions. As I noted there, Nico’s The Frozen Borderline—essentially a combination of expanded editions of her The Marble Index and Desertshore LPs—is missing two alternate versions that appear as bonus tracks on the much slimmer 1991 expanded edition of The Marble Index. The Frozen Borderline was otherwise assembled so conscientiously it’s hard to believe no one involved with the project was aware of those other alternates. And there was certainly enough space for those two tracks, since there’s a ten-minute gap of silence near the end of the second disc (more details later in this post).

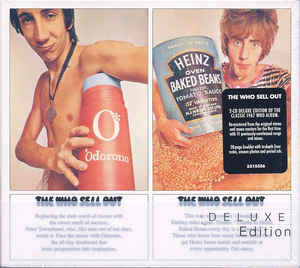

Here are a couple other projects to pick on. The 1995 single-disc expanded The Who Sell Out had nine bonus tracks, all of them really good stuff as bonuses go. The 2009 two-CD expanded The Who Sell Out had no less than 27 bonus cuts, in addition to stereo and mono versions of the LP. So that must have been definitive, right?

Not quite. Two pretty good outtakes from the first half of 1968, “Glow Girl” and “Melancholia,” are on the single-disc edition, but not the much larger two-CD one. Maybe it was felt that, as the only tracks postdating 1967, they’re out of place, and they are both available on other Who archive CDs. But it really wouldn’t have displeased many, if any, Who fans to put them on the larger set too.

By the way, it’s a little curious that while the Who’s debut album, My Generation, got a five-CD box treatment—and Tommy, Quadrophenia, and Live at Leeds have all gotten imposing boxes—none was done for The Who Sell Out, even on its 50th anniversary, which would have been a good excuse to knock it out. Certainly it could have been enlarged with some more singles and the numerous demos Pete Townshend was churning out at the time, as he did throughout the Who’s prime.

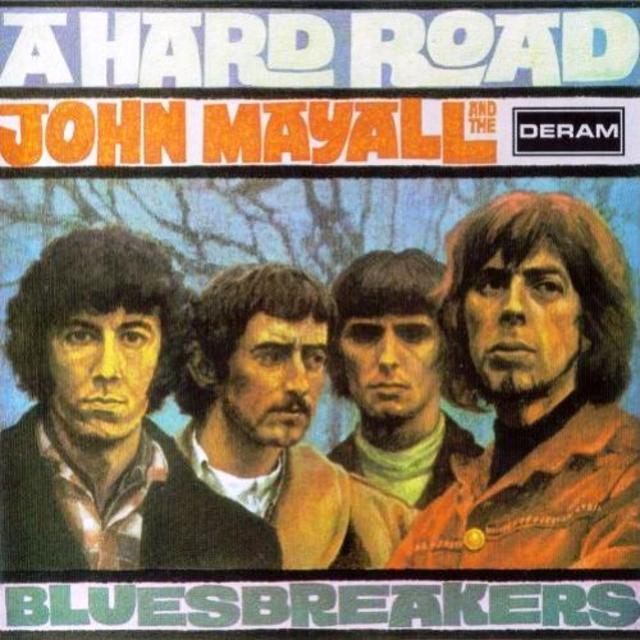

Another less legendary, but still highly worthwhile and historically notable, album from that era that generated two editions with a lot of overlap was John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers’ A Hard Road, the only LP they recorded with the pre-Fleetwood Mac Peter Green. The 2003 double CD expansion had 22 bonus tracks. These are necessary to get a fuller overview of the Bluesbreakers’ Peter Green era, as they also encompassed numerous non-LP singles, outtakes that only surfaced years later on compilations, and an EP recorded with Paul Butterfield.

The 2006 expanded edition reversed gears and cut the running time to a single disc and 14 bonus tracks, inevitably removing a bunch of stuff from the two-CD version. Yet it also has four songs from a January 23, 1967 BBC session that are not on the double CD. Well hey, at least you get different liner notes with the 2006 edition…

Put out an expanded edition that’s not very expanded, even when it’s known there’s a lot of good or at least interesting unreleased material from the same era. Lots of discs could be named here, but let’s focus on a very recent one. The 50th anniversary edition of Beggars Banquet had little in the way of extras, even though quite a bit of material the Rolling Stones cut during the sessions has been bootlegged. Instead, you got a package with a vinyl LP; a bonus vinyl disc with an original mono mix of “Sympathy for the Devil”; and a flexidisc with a telephone interview Mick Jagger gave to a Tokyo journalist in April 1968. And no historical liner notes.

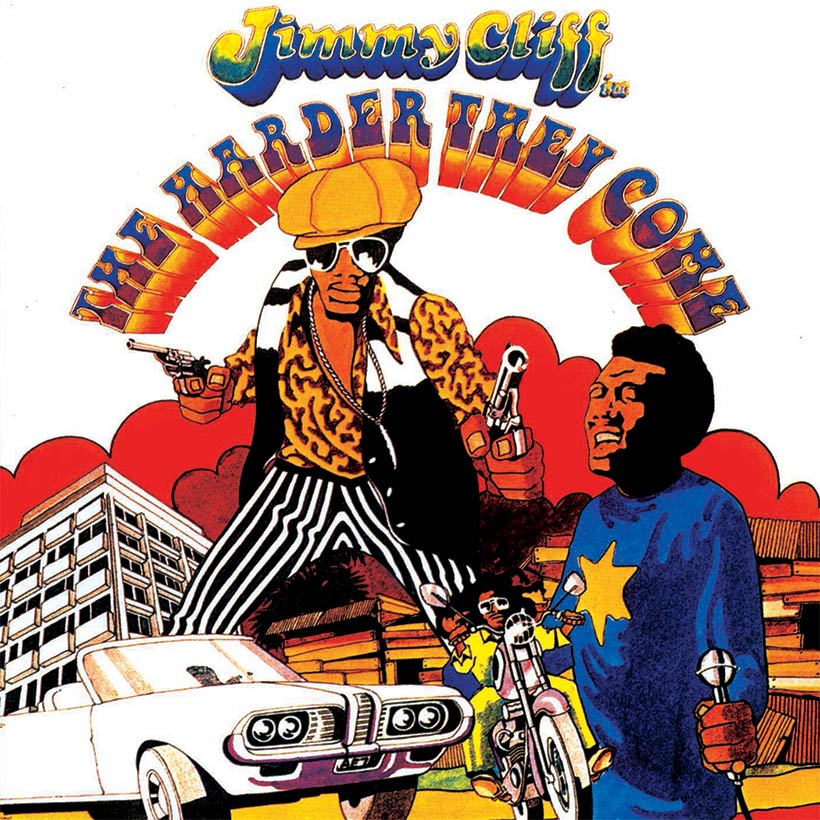

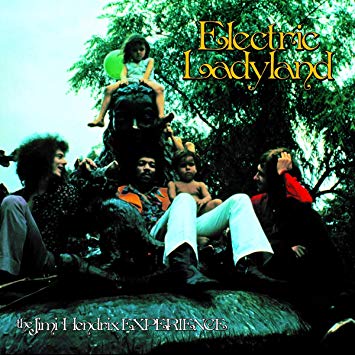

Coming out at the same time as much more substantial 50th anniversary editions for The White Album, Electric Ladyland, and even The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, it looked pretty paltry in comparison. But hey, at least it had both the original banned “toilet graffiti” cover and its clean white “invitation” replacement.

Why aren’t the Rolling Stones getting aboard the super deluxe box train, when even the Beatles have finally embraced it with zeal? I read speculation that the outtakes were not made available for legal reasons, and while specifics weren’t given, at a guess maybe it has something to do with the rights to songs written by Mick Jagger-Keith Richard (and for that matter Bill Wyman) that haven’t previously been released in any form. If that’s the case, it’s too bad, though you can suffer with the hissy quality of the unreleased material on bootlegs in the meantime. If a legal dispute’s holding it up, the big losers are the fans.

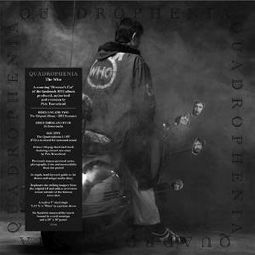

Put a note promising yet more extra material on a website or download that never goes up, or is never made available. Like some other Who albums, Quadrophenia has been issued in a super deluxe edition guaranteed to relieve you of your paycheck faster than Whole Foods’ shopping cart. This five-CD extravaganza includes the original album; 25 Townshend solo demos which illustrate how meticulously he sketched out the material, also including a few songs that didn’t make the album, though these are weaker and more ill-fitting for the opera than the ones that were selected; a disc of 5.1 SurroundSound mixes of eight (and just eight) of the album’s seventeen tracks; a seven-inch vinyl single of “5:15” and the non-LP B-side “Water”; a 100-page hardback book with an essay by Pete Townshend, illustrated with rare photos and documents; and assorted other memorabilia.

So far so good, pretty much. The extras aren’t so great that you’d nominate this as one of the best expanded editions, but certainly there’s a lot of bonus material, if of variable value. But there’s a glitch in those extras, if one seldom commented upon, even by Who fanatics.

Though the book promises an online area of yet additional bonus content via “Q-Cloud,” the link provided to access it simply brings you to a “not found” page. I hadn’t tried it for a few years, but I just tried it again, and it coughs up the same result. It’s an unconscionable rip-off that, if nothing else, is in keeping with Pete Townshend’s failure to finish off some of his most ambitious ‘70s projects, the early-‘70s album/movie Lifehouse being the most famous of those.

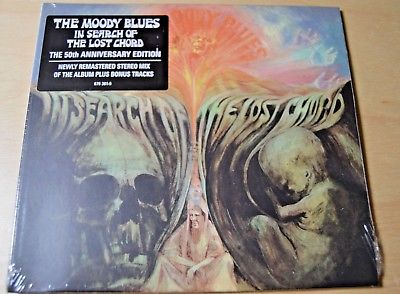

Bloat the box with new mixes that were never even previously commercially available. This was done on a 50th anniversary edition from 1968 that didn’t get too much attention, at least compared to the likes of The White Album, Electric Ladyland, or even Skip Spence’s Oar (the last of which wasn’t technically a 50th anniversary edition, as that album didn’t come out until 1969, though it was recorded at the end of 1968). The 50th anniversary deluxe of the Moody Blues’ In Search of the Lost Chord had three CDs and two DVDs (one of the DVDs boasting visual content, the other various audio versions of the album). One of the CDs was almost solely devoted to a “new stereo mix” (the “original stereo mix” is featured on a different CD).

I’m aware some collectors get real enthusiastic about new mixes and 5.1 SurroundSounds (for those who have the hi-end equipment to play them). Maybe some of them would feel I have bad ears, or lack appreciation for the nuances different mixes bring out. But I know I’m not alone in my criticisms of filling up space on expanded editions with these. As one fellow critic, who’s heard and written about an enormous amount of vintage rock, wrote to me recently: “I have no time at all for new remixes and remasters of albums that sounded perfectly fine when they were first released. Why remix a classic Beatles album to make it sound like a modern recording? Of course, we both know that answer to that one: $$$ and £££.”

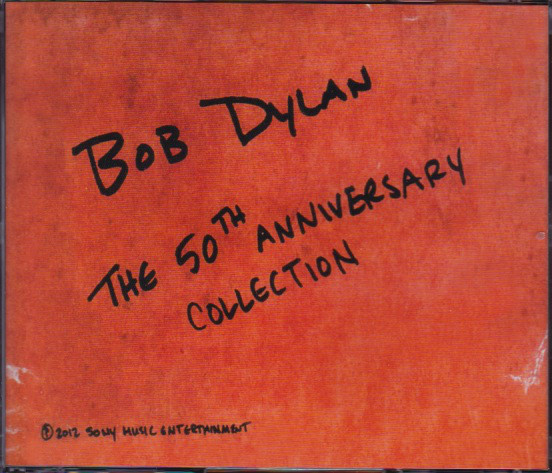

Put out a bunch of unreleased material that could have been used on an expanded edition for a few hours, or as an edition so extremely limited that it’s sold out before most fans are even aware it’s available. Sometimes this has been done, the usual speculation goes, to extend the copyright on material that’s in danger of going into public domain if it’s not officially released in some fashion. In 2012, Bob Dylan didn’t bother to make a secret of this in the four-CD The Copyright Extension Collection Vol. 1, a four-CDR (not a typo, CDR) compilation of 1962 outtakes and live recordings. Reportedly only 100 copies released, and then only on Europe.

Naturally these were quickly bootlegged/file-shared, and most Dylan fanatics knew how to get those non-original copies if they wanted. On their own, however, the first two CDs—comprised of studio outtakes—would have made for the logical bonus discs for an expanded edition of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. There are too many multiple versions to make this compulsive over-and-over listening. But there’s some good stuff here, and it’s certainly all of significant historical value, especially since it includes some original compositions and covers that didn’t make the LP.

Dylan and Sony would do this again for the years 1963 and 1964, rather than make at least some of that material widely available on standard expanded editions of his third and fourth albums, The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan. It might seem churlish to slam Dylan for these copyright extension exercises when he’s been far more willing than most legends to authorize official reissues of tons of his vault holdings, on the lengthy and still-ongoing Bootleg Series. Still, it would have benefited from both over-the-counter availability and historical liner notes/photos. Sony and Dylan certainly can’t be surprised that it’s been heavily bootlegged/unofficially circulated.

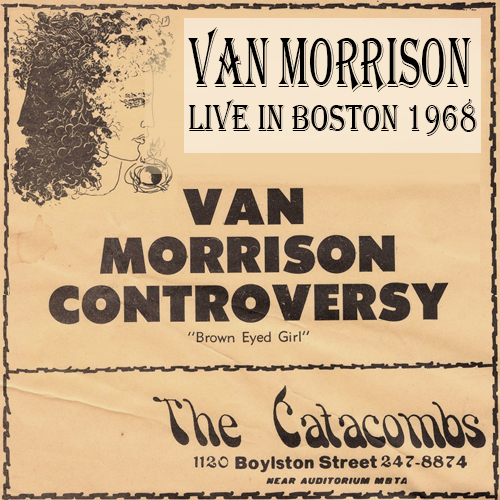

Van Morrison recently super-briefly issued some rare material in a different way. For just a few hours on November 7, a 64-minute live recording of an August 1968 Boston gig, his voice and acoustic guitar backed by just bass and flute, was available on iTunes UK. Although the fidelity’s not great, it’s part of the bridge between “Brown Eyed Girl” and Astral Weeks. Maybe the sound quality isn’t considered good enough for a general release, but it might have made an interesting disc in an expanded edition of the Astral Weeks album. As my lengthy story on the material’s release notes, there are apparently no plans for such a project where Astral Weeks is concerned.

Hidden bonus tracks. They’re not just an expanded editions, of course. One of the most aggravating was on a box set by a blues performer where the bonus track was not at the end, but at the beginning, requiring you to put your player on rewind so it went back before the start of track 1. My cheap CD player was unable to do that, and there was no refund or replacement conventionally playable disc with the bonus track when I let the label know—not much sympathy at all for my situation, in fact.

Most hidden bonus tracks—meaning songs unlisted in the packaging—are at the end of CDs, not the beginning. Often they’re preceded by a gap of silence, ranging from ten seconds to ten minutes. Which means they’re missed by those of us who are such ignoramuses that we unthinkingly eject the CD when it goes silent, instead of taking care to notice that the clock’s still ticking.

It’s back to Nico’s The Frozen Borderline for a prime example. An alternate version of “Frozen Warnings” at the end of the second disc of plays as an unlisted “hidden” track after a ten-minute gap of silence. I suppose the logic here might be, what a pleasant shock it is to suddenly hear music come out of the speaker after you think the album’s ended, while you’ve gone to wash the dishes or check your email. But such is the harried pace of modern life that plenty of people who’ve paid for the disc might eject it after the music’s over, or they think it’s over, without ever suspecting there’s more to come. Maybe I’ve even missed some hidden tracks myself.

My advice to record labels: don’t be cute. Don’t even put an unlisted track at the end if there’s no gap of silence. Let people know it’s there; if they’re getting an expanded edition, they do want to hear everything (and know what it is, in the liner notes/annotation). It’s kind of like those DVDs that had “easter eggs” where you couldn’t access unlisted bonus features unless you figured out exactly what to click and hover over—if you even knew the bonus features were there. That seems to have mostly or wholly disappeared from the DVD (and now Blu-ray) business, as it should from expanded music CDs.

In my past couple posts, I’ve praised some extended editions, and harped on a bunch of them whose flaws range from imperfection to downright annoying. Most extended editions, however, fall way between those two extremes. They offer enough extra material to interest committed fans, but not such exciting bonuses that you want to play the add-ons nearly as much as you play (or at least played, back when you had the bare disc) the original album. Again, just a couple examples of middle-value extended editions, which happen to be from the same label, the same era, and the same region:

The two-CD “Legacy Edition” (named after Columbia/Sony’s Legacy imprint, specializing in reissue) of Santana’s self-titled 1969 debut LP more than doubles its length with a couple alternate takes; previously unissued sessions for the original, unreleased album, produced by David Rubinson, including a song (“Fried Neckbones”) that wasn’t cut when the LP was redone from scratch a few months later; and seven songs from their legendary Woodstock set, four previously unreleased. Do I appreciate having this material available? Sure. Have I listened to it a lot? No, and it’s not on the level of the original LP, except for some of the Woodstock set, especially the one that’s long been well known from the festival’s soundtrack album and performance in the Woodstock movie, “Soul Sacrifice.”

The two-CD Legacy Edition of Janis Joplin’s last album, Pearl, likewise more than doubles the length of the LP with some demos/alternates/outtakes (half previously unreleased) and a live disc of material recorded in mid-1970 during the Festival Express tour in Canada (almost have previously unreleased). Likewise: good to have, I like it when I hear it, I appreciate its historical value. But I haven’t played it too often, and it’s not memorable in the way the Pearl LP is.

At this point some of you, including some who are actually in the music business and record industry, might be thinking that I’d rather expanded editions weren’t around at all. Or even worse, you might be reconsidering whether the record business should be doing expanded editions at all. No! Don’t stop! I do generally relish that extra material, whether it’s just that stray barely-different alternate take or heaps of demos that are actually revelatory.

Just because the bonuses are rarely on the level of the core albums doesn’t mean they’re not at the very least historically interesting, and at the very most vastly entertaining, to hear. Even the crummy cuts sometimes yield insights into the creative process. The usual gap in quality is an expected testament to the editing skills of the musicians, producers, songwriters, and labels when it came to determining what should be on the finished album.

And if I don’t especially feel the need to get the core albums along with the bonus material, or care too much about the remastered/remixed versions, I’ll end on an upbeat note by praising one of those relatively uncommon instances in which a bunch of extras are packaged on their own. Let’s give a hand to last year’s Big Brother’s Sex, Dope and Cheap Thrills. As I wrote when I put it in the Top Ten of my year-end list:

Not an expanded Cheap Thrills (there was already one of those without much in the way of extras), this two-CD compilation is comprised almost entirely of outtakes from the sessions. Twenty-five of the thirty songs are previously unreleased; the previously available ones are on out-of-the-way or expensive compilations that even committed Joplin/Big Brother fans might have missed; and the one non-studio cut is a good hitherto unissued live version of “Ball and Chain” (Winterland, April 12, 1968).

There are good, though not book-length, liner notes by drummer David Getz, and an appreciation by Grace Slick that’s thoughtful and long enough not to look phoned in. And you can get all this as a standalone release, instead of having to buy it as part of an expanded Cheap Thrills edition that compels you to buy the original album—which you probably already have in at least two formats—all over again. And the double-CD sold for a reasonable $14.98 plus tax at my local record store. Hey, labels (and artists), pay attention: this is the way to do it!