Releases of previously unissued vintage rock material are routine in the record business these days. Not a week passes, it sometimes seems, without compilations of unavailable or mostly unavailable tracks, many of which would have been inconceivable in the 20th century. Two CDs of Abbey Road outtakes? David Bowie 1969 home demos? A multi-disc package built around Bob Dylan-Johnny Cash collaborations from the ‘60s? All are out this fall alone.

Back in the actual late ’60s, however, rock albums of unreleased material that were motivated by their historical importance were virtually unknown. That’s not to say, of course, that LPs comprised of or built around non-recent recordings hadn’t appeared since about the time rock started. Usually, however, these were vault leftovers that were only put out to exploit the success of an artist with tracks that were unlike and/or not nearly of the same quality as what had made them famous. Often these were attempts to squeeze the last juice of a lemon after artists had passed their peak, or out of spite after they’d reached a much higher level of success with a different label.

Admittedly, it can be a fine line as to whether an archive release built around previously unheard cuts is exploitative, a sincere attempt to document history, or some of both. Certainly all of the early LPs with some element of historical importance were compiled at least in part to make some money, and not simply provide listeners with a vital public service. But almost as certainly, they were also devised at least part due to the urge of someone — whether a producer, label staffer, artist, or someone else — to give fans the opportunity to hear music that had no chance of selling too well, but was crucial to appreciating the history of the musicians. And, not incidentally, was often really good on its own terms, and deserved to be heard in any case.

Here’s a list of a dozen notable early rock LPs that archived unreleased (or almost wholly unreleased) recordings, from the late 1960s to the late 1970s. I feel like I might have missed something, but I gave my vinyl collection a once-over in addition to thinking hard about what qualified. I know I haven’t listed some that aren’t to my taste, but most or or all of these should have some appeal to big fans of rock from the mid-‘60s through the early ‘70s.

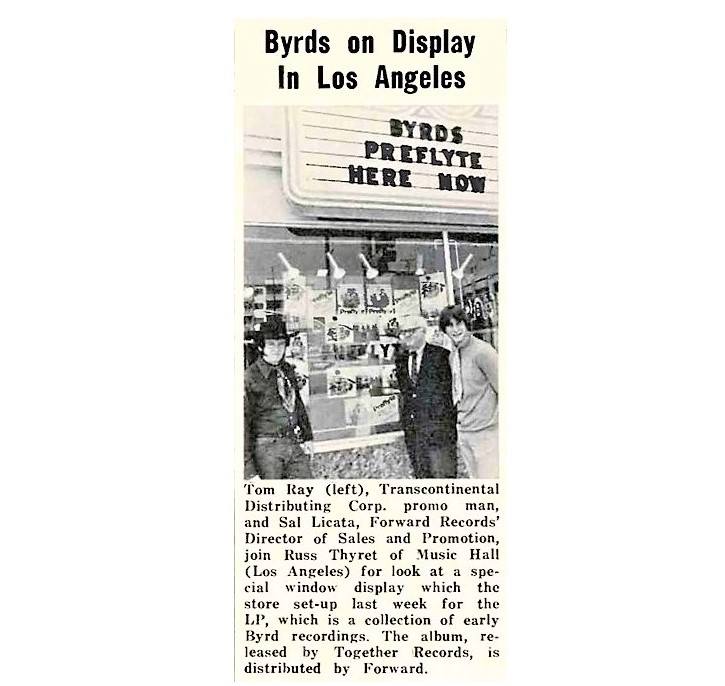

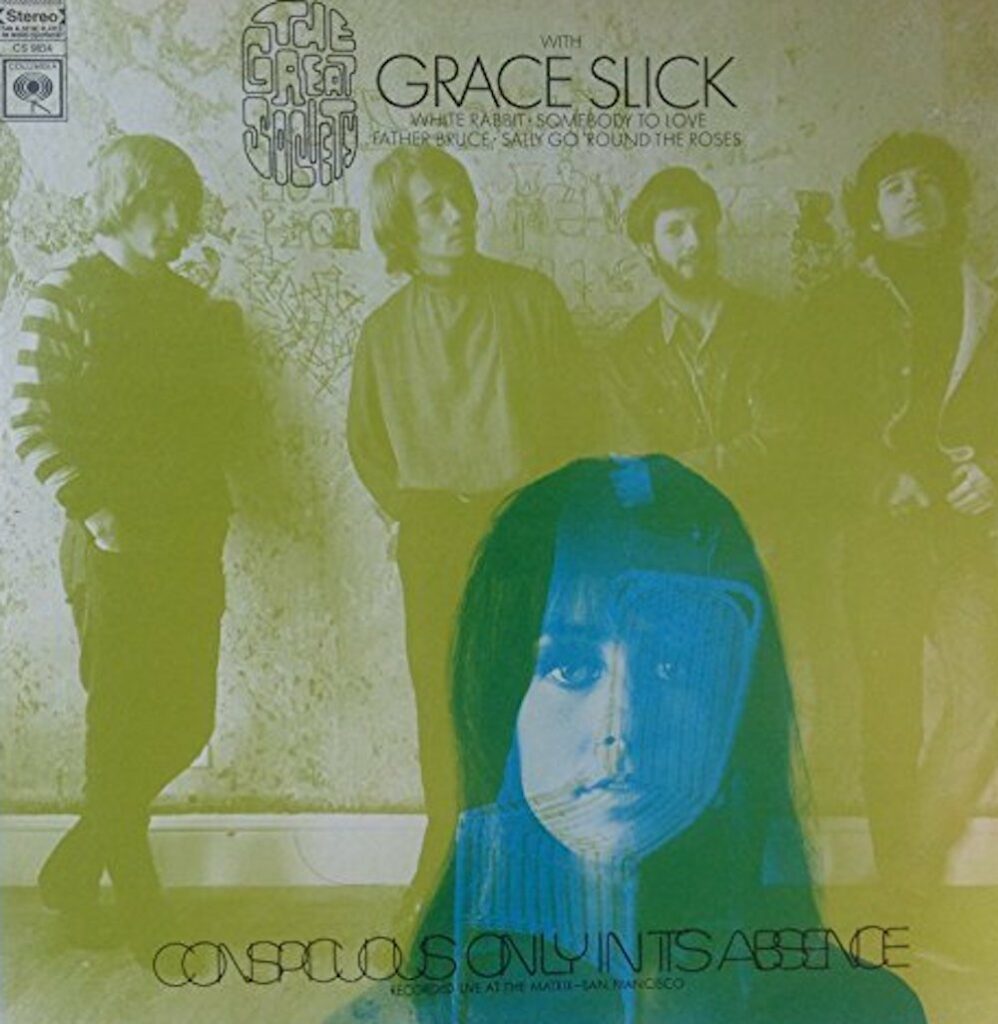

The Great Society, Conspicuous Only In Its Absence/Collectors Item: How It Was (1968). Strictly speaking, these were two different LPs. I’m putting them into one listing as the second came out not long after the first; they were both taken from live 1966 tapes at the same venue, San Francisco’s Matrix club; and have since often been packaged together, as a double LP and then a single CD.

These records almost certainly wouldn’t have come out, as least back in 1968, if not for the subsequent huge success the Great Society’s chief singer, Grace Slick, had with Jefferson Airplane. While they were active, the Great Society’s catalog was limited to just one barely distributed single, albeit one that had an early version of “Somebody to Love” (then titled “Someone to Love”) on the A-side. Fortunately they were recorded in pretty good quality at the Matrix in mid-1966, just a few months before they broke up when Slick joined the Airplane.

The first and better of these albums, Conspicuous Only In Its Absence, would have been notable for the inclusion of early versions of “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit” alone. But both records were dominated by original songs, quite a few by Grace Slick, that never appeared elsewhere. Usually these were very good. And as they were among the first and best of the San Francisco groups to integrate free jazz improvisation, Indian influences, and free love-oriented lyrics into their rock, the Great Society were also the most underrated psychedelic pioneers from the city, and indeed among the most underrated psychedelic pioneers from anywhere.

Columbia would have never touched these recordings if they couldn’t have prominently placed Grace Slick’s name and image on the covers. Yet the liner notes — by top early rock critic Ralph J. Gleason on the first volume — added some credibility to their status as projects documenting exciting history, not just ringing up some more change while the psychedelic craze lasted. I’ve also heard an interview with a close associate of the band who stated the recordings saw the light of day, at least in part, due to efforts from Grace Slick herself.

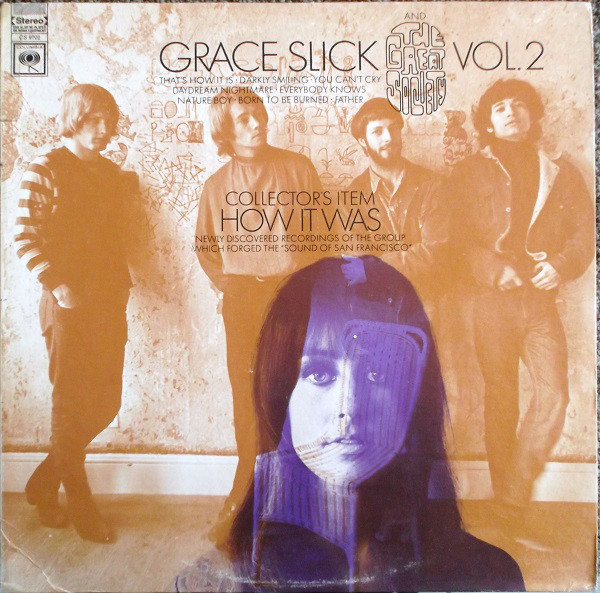

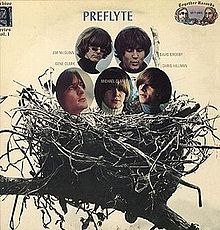

The Byrds, Preflyte (1969). Before they signed to Columbia, and even before they’d played live, the Byrds had the opportunity (via co-manager and early producer Jim Dickson) to use free studio time to practice and refine their sound. They could also tape themselves so they could play back and dissect what they were doing. That alone would make these early tapes, probably dating from around late 1964, of vast historical importance. But even if you knew nothing about the Byrds or didn’t care much about tracing their pre-“Mr. Tambourine Man” evolution, these are hugely enjoyable primordial early folk-rock efforts, from a time the ex-folkies were just learning how to play together as an electric rock band.

This batch of tracks does include a few early versions of songs from their classic 1965 debut LP Mr. Tambourine Man, but also features some really fine originals they never put on their mid-‘60s albums and singles, mostly (but not all) written by Gene Clark. “You Showed Me” would be a hit for the Turtles in 1969. Like the other previously unheard originals, it shows the band trying to emulate the Beatles, but instead starting to forge a distinctive brand of melodic, harmony-laden folk-rock.

It seems like the Byrds themselves had reservations about making this stuff available, as they were only intended as rehearsals/demos of sorts. But almost all of the tracks are excellent. And while Together (the label that first issued these) might have been cashing in on the “classic” lineup’s success, the project was granted some more legitimacy by fairly astute (certainly by 1969 standards) historical liner notes from their early Columbia publicist, Billy James. Subsequent CD editions of the “Preflyte” tapes have added a lot of other tracks, many of them simply alternate versions of songs from the original 1969 LP, some of them worthwhile originals that didn’t make the Together album. The 1969 edition does contain the bulk of the best performances.

Various Artists, Early L.A. (1969). This is the most marginal inclusion on this list, and not just because it’s kind of a grab bag compilation of mid-‘60s outtakes by notable Los Angeles acts, most of whom were associated with producer Jim Dickson. Historical liner notes are usually the surest indication that some sense of altruistic purpose was involved in assembling an archive release. But the packaging on this LP, at least on my copy, is subpar even by the low standards of ‘60s budget LPs. For no apparent reason, the artwork mimics a chart by Los Angeles Top Forty AM station KFWB, complete with dated early-‘60s-looking black-and-white xerox-quality photos of disc jockeys. The liner notes are vague to the point of uselessness. It’s hard to even tell who the specific artists are for every track, as, irratatingly, the composers are given for each song on the back cover, but the performers themselves aren’t even listed, though some of the artists are named on the front.

But for all its shabby presentation, the contents are fairly interesting, entirely unreleased at the time, and still hard in many cases to find elsewhere. There are early, possibly pre-Byrds solo efforts, if not too distinguished, by David Crosby; a pre-Columbia Byrds outtake, “You Movin’,” that’s different from the one on Preflyte; an unplugged early pseudo-Beatles recording by Gene Clark, Roger McGuinn, and David Crosby (“The Only Girl”) that’s the earliest surviving Byrds, or sort of Byrds, performance on tape; a couple very early sort-of folk-rock hybrids by Dino Valenti; a couple nice mid-‘60s folk-rock outings by bluegrassers the Dillards; and, of least interest, a couple Canned Heat cuts.

Like the Byrds’ Preflyte, this came out on the short-lived Together label, whose apparent purpose was to issue archive anthologies such as these. Who knows what other neat oddities it might have exhumed from the tombs. But nothing else of note was forthcoming from the company, perhaps because the time was too early for such specialized dives into the vaults.

The Yardbirds, Live Yardbirds: Featuring Jimmy Page (1971). Arguably this wasn’t an official release, since it was only on sale very briefly before it was withdrawn from the market after Jimmy Page threatened legal action. Still, it came out on a major label, Epic, a subsidiary of Columbia. It was a historic concert recording of a top British ‘60s group, issued more than three years after it was recorded at New York’s Anderson Theatre on March 30, 1968. It also had historical liner notes by one of the best rock historians (and indeed best liner note writers), Lenny Kaye, who sometimes tempered his hype with phrasing intimating this wasn’t quite the holy grail he was making it out to be. Most amusing excerpt: “And from the very start, you know it’s about to happen, The Greatest Concert Ever, at least of this week…”

No doubt it was issued to exploit Page’s superstardom in Led Zeppelin, his prominent subtitle billing serving as evidence. It nonetheless made for an interesting document of the Yardbirds’ Jimmy Page lineup, who didn’t record that much, and with a few exceptions didn’t make very good studio tracks. And not many live LPs of British Invasion bands were on the market at all during the actual British Invasion.

It turned out, though, that this album had its share of problems that went beyond the failure of Page and Yardbirds to approve its release, either back when it was recorded or in 1971. The tracks were overdubbed with inappropriate bullfight-type cheers. The actual performances weren’t all that great, or at least the Yardbirds in top form, either compared to the Eric Clapton/Jeff Beck eras or relative to the best live tapes of the Page lineup (though those had yet to circulate in 1971). Page’s playing is the highlight, though, and while the versions of mid-‘60s classics are no match for the Beck lineup originals, it did have a pre-Zeppelin arrangement of “Dazed and Confused” (titled “I’m Confused”), which the Yardbirds never cut in the studio. A cover, if not a great one, of another item not found on ‘60s Yardbirds releases (Garnet Mimms’s “My Baby”) was another bonus; Page played well on his acoustic guitar showcase “White Summer”; and “I’m a Man” was given an extended arrangement that made it quite different from either the Clapton or Beck versions on the Having a Rave Up with the Yardbirds LP.

Almost fifty years later, the material came out with much better sound, and minus the fake crowd noise, on the Page lineup-endorsed Yardbirds ’68. While better, that release also had some problems, namely the exclusion of singer Keith Relf’s between-song comments and some editing of the tracks that removed sections that can be heard on the long-bootlegged original Epic LP. My detailed review of Yardbirds ’68 can be read here.

Soft Machine, Faces and Places Vol. 7 (1972). Starting in the early 1970s, Giorgio Gomelsky arranged to put out a lot of historical tapes he’d made through the French label BYG. While these included a bunch of big names like the Yardbirds (whom he’d managed and co-produced for their first few years), the Animals, the Spencer Davis Group, Graham Bond, and the Steampacket (including John Balrdy and the pre-fame Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll, and Brian Auger), most of these were pretty scrappy live tapes or demos. An exception, even if these were also never intended for release, were nine demos he produced of the Soft Machine in April 1967. This almost amounts to a lost Soft Machine first album, especially as just one rare single was released by the 1967 lineup with Daevid Allen on guitar. As I wrote in my chapter on Giorgio Gomelsky in the extended ebook edition of my book Urban Spacemen & Wayfaring Strangers: Overlooked Innovators & Eccentric Visionaries of ‘60s Rock:

“In addition to being historically important (comprising most of the available material by the early version of the band with Daevid Allen on guitar), it’s also enjoyable and innovative early British psychedelia, with incessantly inventive tempo and melodic shifts, alternately goofy and affecting lyrics, and Robert Wyatt’s soulful singing. There are strong hints of jazz and the avant-garde, though these are still subservient to a hummable pop sensibility. That invigorating collision of elements is best heard on ‘Jet-Propelled Photograph’ and the emotional ballad ‘Memories.’”

These nine demos have been reissued so many times under so many different titles that it’s useless, if not impossible, to list them all. It seems like they’ve always been obtainable since first appearing (sometimes piecemeal on various-artists compilations) in the early 1970s. Gomelsky’s ‘60s archival tapes by other artists are pretty much for completists, an exception being a glorious ten-minute “Blues Raga” by the superb British folk guitarist Davy Graham, probably recorded around 1967. That and the less memorable Graham rarity “When Did You Leave Heaven?” were part of BYG’s various-artists compilation Rock Generation Vol. 8, but only added up to most of an LP side, not a proper album.

The Kinks, The Great Lost Kinks Album (1973). Here’s another LP that wasn’t approved by the band, Ray Davies actually taking action that resulted in it being deleted from Reprise’s catalog in 1975. Unlike Live Yardbirds Featuring Jimmy Page, however, there was no post-production nonsense, and the quality was higher, if not quite on par with the Kinks’ proper studio albums. Most notably, it featured a wealth of previously unreleased outtakes from their late –‘60s prime. While there was a bit of stuff that had been officially issued, back in 1973 those cuts—the great 1966 B-side “I’m Not Like Everybody Else,” and the 1969 UK single “Plastic Man”—weren’t so easy to find. And the outtakes weren’t far below, and sometimes about on the same level, as the songs on their official LPs, especially the Village Green Preservation Society leftovers “Misty Water” and “Mr. Songbird.”

All fourteen tracks have come out on CD reissues, even if they’re scattered among so many discs that collecting them all takes a hefty investment. There’s one reason to hunt down the original Reprise LP (not easy or inexpensive to find in good condition), despite its ugly and inappropriate cover. The insert features detailed liner notes by noted rock critic John Mendelsohn that trash the Kinks’ then-recent output—which just happened to have been released not on Reprise, but the label the band jumped to, RCA.

Jefferson Airplane, Early Flight (1974). Despite the ugly cover, this was a highly worthwhile, as the back sleeve proclaims, “collection of songs never before released on an album.” A few tracks (the 1966 B-side “Runnin’ Round This World” and the 1970 single “Mexico”/“Have You Seen the Saucers”) had been available on low-selling 45s, but everything else was unveiled here for the first time. And some of the ’65-’67 cuts were very good, like their version of “High Flyin’ Bird,” one of several items on the LP done with original woman singer Signe Anderson in December 1965. The Surrealistic Pillow outtakes “Go to Her” and “J.P.P. McStep B Blues” were as good as the secondary songs on that classic LP. A couple numbers were more obvious rejects/filler, but the rest certainly bolstered their reputation as one of the great ‘60s bands—not that their reputation was in need of a boost. It also gained some authenticity/official endorsement from the brief but informative liner notes by Airplane manager Bill Thompson, which clearly and succinctly explained the origins of each selection.

The Velvet Underground, 1969 Live (1974). Actually billed to “the Velvet Underground with Lou Reed,” probably this wouldn’t have come out if Reed’s early solo success hadn’t been available to exploit. Still, this double LP was hardly a quickie ripoff, with 103 minutes of music. Of greater value than its sheer length was its astronomically high quality. Fifty years after these fall 1969 performances in San Francisco and Dallas clubs were recorded, it’s still a contender for the best live rock album of all time. As I wrote in my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Live, it’s “not just the Velvet Underground at the peak of their powers. It’s as good as any rock group has ever sounded live.” It also captures the group at a point where they were varying the songs considerably from the studio versions, and sometimes substantially improving them.

It’s nonetheless kind of amazing that a double album was green-lighted for what in 1974 was still very much a cult band that had never sold many records, even if it did sell for a lower price than the usual double LP. It might have marked the first time a cult band was so posthumously honored, if not for the presence of Reed, who did lend the project some star power.

It probably wouldn’t have gotten approved for release (on a major label, no less), however, if not for the dedicated efforts of rock critic-turned-Mercury A&R man Paul Nelson. He discussed how he pushed the project through with humorous detail in a chapter he wrote in the mid-1990s for an unpublished anthology on the history of Mercury Records, now available in the 2011 book Everything Is an Afterthought: The Life and Writings of Paul Nelson. During one heated exchange, Mercury president Irwin Steinberg revealed to Nelson that it never would have come out “if one of our Nashville artists hadn’t gotten sick and had his LP delayed!”

While I’m not much for liner notes that eschew historical detail for fan appreciation, the brief but excellent notes to 1969 Live by singer-songwriter Elliott Murphy are an exception. “Rock’n’roll people tend to live on the edge,” he wrote. “That’s what this album is all about. Rock’n’roll has always been and still is one of the few honest things left in this world. That’s what this album is about…I hope parents will still get scared when they find their daughter listening to this music.”

The Who, Odds and Sods (1974). The Who took more interest in their own history than any major band of the 1960s and 1970s. So it made sense that they were the first such act to oversee a vault-combing collection themselves, Pete Townshend even writing track-by-track liner notes. All but one of the cuts were previously unreleased, and even the one that had seen the official light of day, the High Numbers’ 1964 single “I’m the Face,” wasn’t easy to find in 1974. Everything else was from 1968-72, doing much to fill in what had occupied them in the gaps between rock operas.

Odds and Sods’ contents aren’t great, and certainly not a match for their official LPs and singles. They don’t even feature much of their very best unissued pre-1973 stuff, a lot of which has since come out on CD. And the 1998 expanded CD reissue, which about doubles the length of the LP, has some good outtakes (like “Time Is Passing,” a 1967 studio version of “Summertime Blues,” a 1964 cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Baby Don’t You Do It,” and an alternate version of “Mary Anne with the Shaky Hand”) that are as good as any selections from the original LP, and better than some that made the initial cut. Still, at the time it was not only a valuable supplement to the Who’s pre-mid-‘70s discography. It was also a heartening indication that some major rock musicians might start to take some more interest, and pride, in exhuming some of their leftovers for archive compilations.

Bob Dylan & the Band, The Basement Tapes (1975). A couple unreleased 1960s Dylan recordings achieved particularly mythic status before gaining official release. One, his “Albert Hall” May 1966 concert (actually recorded in Manchester and bootlegged as a London Albert Hall performance), wouldn’t come out until 1998. The other was the extensive collection of tracks he cut in 1967 with the Band, although it wouldn’t be fully realized for decades just how extensive those were. Although this 1975 double album only included a relatively small fraction of them, its appearance nonetheless marked the first time an artist of this stature had issued such widely hailed bootlegged material. And the package did include most of the very best songs from the era, like “Tears of Rage,” “Million Dollar Bash,” “Too Much of Nothing,” “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” “Nothing Was Delivered,” “Open the Door, Homer,” “Tiny Montgomery,” and “This Wheel’s on Fire.”

The presence of eight Band songs sans Dylan—some recorded in 1967, but actually spanning 1967-75—did dilute the concept. So did the 1975 overdubs to some of the tracks. What’s more, it was missing some of the best tracks from the sessions that appeared on bootlegs, like “I Shall Be Released” and “Mighty Quinn.” Some Dylan fanatics contented that some of the versions selected for the official release weren’t nearly as good as some bootlegged ones. As Paul Cable wrote in Bob Dylan: His Unreleased Recordings, “What sort of a sick joke is it to have Quinn the Eskimo on the cover but not on the record? It is very odd indeed that there should have been such devastatingly glaring omissions…It is almost as though someone at Columbia actually had an interest in keeping the bootleg scene going.”

This was remedied by the 2014 six-CD box The Basement Tapes Complete, which included all of the Dylan-Band recordings from the 1975 double LP (without overdubs) and a mind-blowing 138 tracks in all. Understandably, that’s rendered the 1975 version of The Basement Tapes superfluous to many listeners, unless you’re a Band completist. But it was still a major signpost in archival rock’s road to being taken more seriously by the record industry, and viewed as more marketable, with the 1975 set making #7 in the charts.

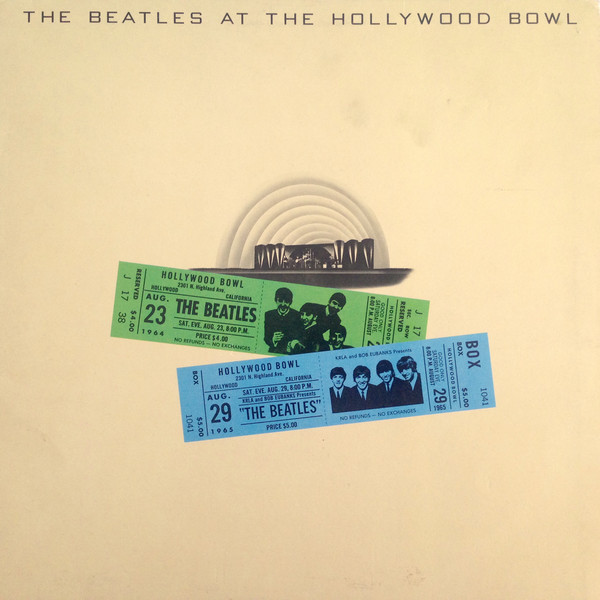

The Beatles, At the Hollywood Bowl (1977). Naturally a live mid-‘60s Beatlemania recording by the greatest band of all time was a milestone in the evolution of the archival rock industry. Of course, even at the time it appeared, many Beatles fans griped about imperfections. These went way beyond the unavoidably mediocre fidelity of the recording, the screaming audience making it hard both to capture the group on tape and for the band to hear themselves. The combination of tracks from their 1964 and 1965 Hollywood Bowl shows meant that a number of songs from each year were omitted. Its belated appearance on CD in 2016 improved but didn’t wholly fix things, adding just four bonus tracks. The Hollywood Bowl concerts—from August 23, 1964, August 29, 1965, and August 30, 1965—haven’t been issued in full, though they’ve long been available on bootleg.

Arguably, the original LP (and more so the expanded CD) are enough for the average listener, though there are enough non-average Beatles fans to make the absence of all the Hollywood Bowl material from their official discography irritating. The original LP did gain some authority with a fairly lengthy back cover liner note by producer George Martin (reprinted in the CD booklet, which adds a much lengthier historical essay written specifically for the 2016 edition). Martin’s note is dated by an exchange he reports with his nine-year-old daughter, who asked him, “Were they as great as the Bay City Rollers?” Replied the too-gentle Martin, “probably not,” though he added in his notes, “some day she will find out.”

The year 1977 actually saw two Beatles archival releases, the other being a double album from December 1962 live Hamburg tapes (not included on this list of a dozen key releases owing to its substandard sound quality). Yet the Beatles wouldn’t endorse another archival release until the mid-1990s, when the three-volume Anthology series of mostly unreleased material was generated to coincide with the documentary and book projects of the same name. And it wasn’t until the last few years, with the Sgt. Pepper/White Album/Abbey Road box sets, that they’ve really gotten fully behind a more diligent and thorough archival/vault program.

The Easybeats, The Shame Just Drained (1977). It might not have been on the magnitude of the original Basement Tapes compilation or Beatles Hollywood Bowl LP, but this well done anthology served notice that much less celebrated acts would start to enter the archival game. Not that the Easybeats were that obscure—they did have one big international hit (“Friday on My Mind”), as well as many huge smashes in Australia, where their career started. But with this Australian LP, we had a high-quality collection of studio outtakes, most drawn from their 1966-67 UK output. Its audience must have been limited to a pretty specialized audience of collectors in 1977, whether in Australia itself or overseas. It would indeed make its way to different continents as an import, Australian rock authority Glenn A. Baker putting the material in context with characteristically meticulously detailed lengthy back cover liner notes.

While none of this was on the level of “Friday on My Mind” or their best singles, some of it was certainly a match for their better LP tracks. “Lisa” and “Amanda Storey” were particular standouts. So was “Mr. Riley of Higgenbottom & Clive,” which not only was one of the group’s few stabs at social commentary, but stands up pretty well to similar (though not the best) efforts from the period by the Kinks.

Who knew that quite a few other Easybeats outtakes and live recordings would emerge after the 1970s, starting with Raven’s fine 1982 LP The Raven EP LP Vol. 2 (sic). But The Shame Just Drained was an indication that the drip of archive anthologies could become a flood—which would indeed happen, to an unimaginable extent that continues to this day.

While that completes my roundup of a dozen key early rock archival releases, here are a few notes about LPs I considered, and why I gave them a miss:

The Fugs, Virgin Fugs (1967). Comprised of outtakes from 1965’s The Fugs First Album, this might be considered too close to the original recording date to be a bona fide archive release. More distressingly, it’s not really that good, and even rawer and more cacophonous than the performances selected for the Fugs’ debut LP, which is saying something. The kicker is that it wasn’t authorized by the Fugs. ESP Records head Bernard Stollman admitted to me years later that “it was very stupid on my part. It was highly improper. I think Ed [Sanders, Fugs leader] had every reason to be enraged that we had put out material that he had not previously determined that he wanted to have out.” For all that, it has some amusing songs, like “Coca Cola Douche,” “New Amphetamine Shriek,” and “I Saw the Best Minds of My Generation Rot.”

Tim Hardin, This Is Tim Hardin (1967). This falls more into the category of someone’s success being fairly quickly exploited than an archival release consciously assembled, at least in part, due to its historical value. Hardin’s first couple mid-‘60s albums for Verve, while not best-sellers, had already established his reputation as a major singer-songwriter when this batch of unreleased circa-1964 material appeared. It’s actually fairly good, due in large part to Hardin’s considerable vocal prowess. But as it’s largely given over to folk and blues covers, it’s not nearly as original or impressive as those early Verve LPs. A similarly flavored batch of ’64 recordings, Tim Hardin 4, came out in 1969.

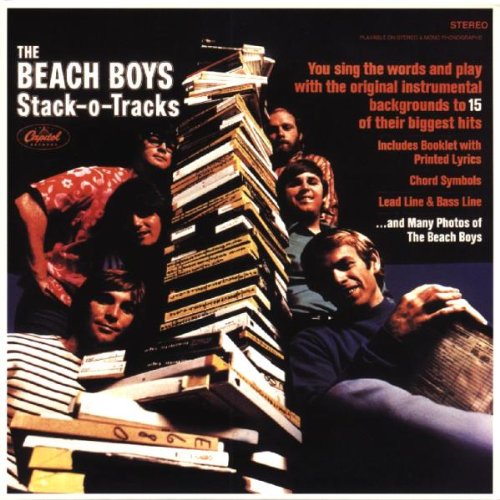

The Beach Boys, Stack-o-Tracks (1968). A one-of-a-kind ‘60s release, Stack-o-Tracks took fifteen Beach Boys songs—largely a mix of hits and some of their standout LP tracks—and issued them without vocals. By presenting the songs’ backup tracks, it was something of a karaoke aid, especially as the cover blurb announced, “you sing the words and play with the original instrumental backgrounds to fifteen of their biggest hits.” A booklet was even provided as a guide for such sing-playalongs. Even overlooking the cuts’ previous incarnations with vocals, it’s really more of a novelty release than an archival collection. Beach Boys fanatics (and there are many) appreciate the opportunity to focus on the instrumental settings. But it’s not something many fans, or maybe even many fanatics, want to listen to many times.

Steppenwolf, Early Steppenwolf (1969). Like the Great Society albums, this was recorded at the Matrix, from a gig on May 14, 1967. Unlike the Great Society, Steppenwolf actually had hits, a couple of which had made the Top Three by the time of this release. This counts as an early historical release of sorts, and has liner notes by Steppenwolf mainman John Kay taking up most of the back cover. I just don’t like Steppenwolf too much, and though I like their two biggest hits, neither of them are here. Most of these songs are bluesier than those hits, and not in a very compelling way. And though I like “The Pusher,” the 21-minute version that takes up all of side two, with an extended freakout intro, is way longer than anyone needs.

Fleetwood Mac, The Original Fleetwood Mac (1971). Dating from 1967, these outtakes are from the period shortly after Fleetwood Mac formed. This is when they were close to a straight blues band, and the music has its share of historic value, dating from around the time they cut their debut LP, or a little before that in some instances. But while it’s okay, it’s not as good as that debut album, or really that memorable. The only exception is the brooding instrumental “Fleetwood Mac,” which swings along with a real verve. These cuts might be better heard as bonus tracks to Fleetwood Mac’s first album than on their own, though the tracks on this LP have never been hard to get.

The Velvet Underground, Live at Max’s Kansas City (1972). Issued a little under two years after Lou Reed’s departure from the Velvet Underground, this smacked a little of Atlantic Records trying to squeeze out some return on their investment. Reed had bailed from the band just before the one LP he recorded for the label as part of the Velvets (Loaded) was released. While Atlantic did record a few cuts with the Reed-less VU in November 1970, they didn’t follow through with an album by that lineup, indicating they didn’t feel it was worthwhile to work without Lou. Maybe they felt like a live recording with Reed on board was their only option for getting another Velvet Underground LP out of the deal, no matter how lo-fi it was. And it was lo-fi, having been recorded from the audience on a cassette at what’s dated as Reed’s last gig with the group on August 23, 1970.

Live at Max’s was issued about six months before Reed broke to a wider public with his second solo album (Transformer), and so can’t be considered an attempt to exploit his post-VU success. The biggest strike against awarding it status as a top archival release, however, is its quality. It’s not that great, in large part because of the thin bootleg fidelity. But the performances aren’t super, either. And the Velvet Underground archive release that did make my top dozen, 1969 Live, is infinitely better.

The Rolling Stones, Metamorphosis (1975). Along with Early Flight, Odds & Sods, and The Basement Tapes, Metamorphosis was part of the first rush of from-the-vault anthologies by major acts. So why isn’t it in the top dozen? Well, it’s not so hot, and dominated by mid-‘60s demos on which the entire band doesn’t play. Those mid-‘60s demos are mostly second-tier, or even third-tier, pop-oriented Mick Jagger-Keith Richards compositions They were cut mostly to help generate cover versions, which they did, though the covers usually weren’t very good either, and in fact often notably worse.

Metamophosis was often slagged upon its release—it even gets the lowest “bullet” rating (“worthless: records that need never (or should never) have been created”) in the original Rolling Stone Record Guide. It’s often been slagged since, though I actually like it more than most critics do. Even those half-assed demos have their modestly tuneful charms. “Don’t Lie to Me,” a mid-‘60s Chuck Berry cover with the full group, is pretty good. Side two has some uneven but fairly interesting late-‘60s efforts, especially the folky Between the Buttons outtake “If You Let Me,” Bill Wyman’s “Downtown Suzie,” and the reasonably strong Beggars Banquet extra “Family.”

But it doesn’t add up to a very strong album. And the packaging takes off plenty of points, with an ugly-as-sin cover and nothing in the way of notes detailing the where and when of the sources. Plus it’s markedly inferior to the tracklist Bill Wyman had proposed, which included a bunch of R&B cover outtakes from their early days.

The Beatles, Live at the Star Club in Hamburg, Germany, 1962 (1977). Certainly this is of vast historical importance, with a double album (slightly different from the US version in its Germany/UK release) of live recordings of the Beatles in late December 1962. There are also plenty of covers the group never put on its studio discs (though just a couple originals, “I Saw Her Standing There” and “Ask Me Why”). So what’s the problem?

It’s no secret, but the sound quality is pretty bad, and the vocals especially muffled. The playing’s kind of sloppy, certainly by the Beatles’ sky-high standards. It’s not nearly as much of a problem, but the liner notes, while fairly lengthy, are fairly useless, and falsely claim the tapes were made when Pete Best was in the band (with Ringo just happening to be sitting in when the tapes were rolling). I’m glad this exists, but it’s not great listening. Fortunately a lot of early Beatles survives in much better fidelity (with much tighter performances) on their early BBC tapes, which likewise feature a lot of covers that didn’t make their official records.