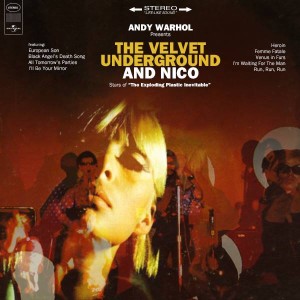

Not long ago, an amusing fake album cover was making the rounds on Facebook. Back in April 1966, the Velvet Underground and Nico had recorded at least nine songs at Scepter Studios in New York, hoping to place the result as an album with Columbia Records. At least, that seems to have been the thinking—Columbia might have asked them to add some material and re-record some tracks, as they did when Verve Records signed them. Had Columbia signed the VU and issued those nine tracks as an album, the LP sleeve might have looked like this:

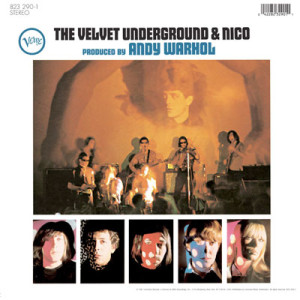

That’s not bad, and of course some of the same imagery from their Exploding Plastic Inevitable multimedia stage shows would show up on the back cover of their actual debut LP, released in early 1967:

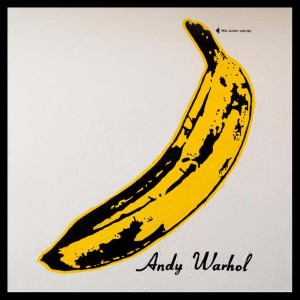

But wouldn’t you agree that the cover of The Velvet Underground and Nico, as released on Verve Records, was much better? For one thing, it was designed by Andy Warhol:

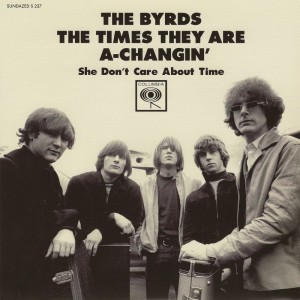

This is iconic, not just another above-average-for-the-time LP cover, in the manner of what Columbia was putting out on the Byrds and Simon & Garfunkel.

Also note that the fake LP has just nine songs, which would have made for rather short running time, even by 1966 standards. Presumably Columbia would have added “There She Goes Again,” a song the Velvets were already doing onstage in late 1965. Indeed, I’m not convinced the VU didn’t do that at Scepter, the song somehow not making it onto the legendary nine-song acetate (including versions and mixes that were different from the ones used on Verve’s Velvet Underground & Nico, and now officially available) made from those sessions.

Norman Dolph, who helped finance the Scepter sessions, remembers Columbia reacting more or less as follows: “There’s no way in the world any sane person would buy or want to listen or put anything behind this record. You’re out of your mind with this.” In the short term, their failure to get a deal with Columbia definitely hurt. Although they quickly signed with MGM subsidiary Verve, that label didn’t put out their debut album for almost a year, by which time some crucial momentum was lost. Verve never promoted the VU too effectively either, though it remains unknown whether Columbia or indeed any company could have promoted such an unusual and daringly experimental band with much success at the time.

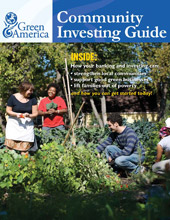

Yet Columbia’s rejection ultimately did quite possibly make the album better. For one thing, maybe Columbia wouldn’t have used Warhol’s design. More importantly, the VU were able to add “There She Goes Again” to the Verve release. Even more crucially, at the insistence of Verve producer Tom Wilson, one more song was recorded for the LP about half a year later, in late 1966, in the hopes of coming up with a commercial track for Nico to sing. That was the classic “Sunday Morning,” though Lou Reed ended up taking the lead vocal, Nico only adding some faint backup vocals. That made a great LP even greater, though the delays were enormously frustrating to a band eager to make their imprint. The full story—time out for a commercial here—is in my book White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day.

For more information about this book, click here.

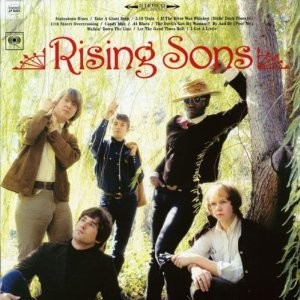

Seeing the fake album sleeve did make me think of other interesting fakes, or at least facsimiles of what might have been, that have circulated over the years. Here’s another, also on Columbia Records:

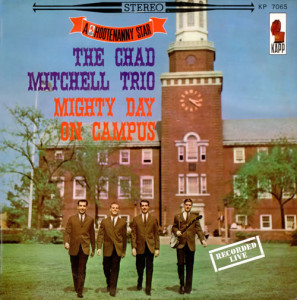

This is a legitimate vinyl LP release on Sundazed. In the mid-1960s, however, the Rising Sons—a supergroup before their time, with Ry Cooder, Taj Mahal, and (at different points) future Spirit drummer Ed Cassidy and future Byrds drummer Kevin Kelley—only managed to release one single, despite recording more than 20 tracks. This collector-oriented release creams off a dozen of them to simulate the album that might have come out at the time, had Columbia had its act together. Issued decades after the Rising Sons broke up, it used previously unpublished color photos to, in the words of Sundazed’s website, “present the Rising Sons’ self-titled debut LP as it might have looked and sounded had it appeared in 1966.”

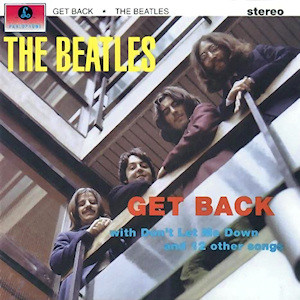

There are numerous other examples of albums that could have come out, didn’t, and have had what-if covers constructed by bootleggers and official record labels. We’ll stop, however, with just this famous one:

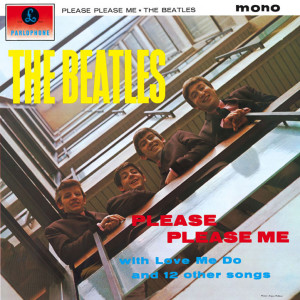

That’s what the Beatles’ Let It Be album might have looked like, had it come out around spring 1969 as originally planned, using the title Get Back instead. They never really agreed on how and when to issue the record, or even what to put on it, which played its own large part in breaking up the group by spring 1970. But in playing around with ideas for the cover, at least they got a great photo out of it, deliberately staged at the same location (a stairwell at EMI Records’ headquarters) where they posed for the cover of their first album in early 1963. What a difference six years made: