The Arizona Diamondbacks didn’t get very far in the 2017 playoffs, getting swept by the Dodgers in the NLDS. There was a memorable moment in the wildcard game they won to advance to that series, however. In their 11-8 win over the Colorado Rockies, reliever Archie Bradley hit a triple — the first triple ever hit by a relief pitcher in a postseason game. It was all the more unexpected coming from a player with a career batting average of .098 and no extra base hits in 61 at bats, which included 37 strikeouts. (Bradley than gave back the two runs his triple knocked in by giving up two consecutive homers in the top of the next inning, but that’s another story.)

These are the kind of moments that make some fans wish so hard for pitchers to continue to be able to bat in major league games, at least in the National League. It’s hard to believe it’s been about 45 years since the designated hitter rule was adopted by the American League, but despite periodic rumblings of discussions that pitchers should bat in both leagues (or not bat in either), it looks like the DH is here to stay in the AL at the very least. Which robs of the unexpected lightning bolts like Bradley’s two-run triple, not to mention the occasional genuinely good-hitting pitcher like Madison Bumgarner, whose 17 lifetime home runs include two on opening day in 2017.

I’m an advocate of having pitchers bat in professional baseball. The overall pros and cons of the DH rule is a lengthy debate for another time that could probably fill up a book, but my rationale is one I never hear: that the game’s simply fairer when each player has to play both offense and defense (or go out of the game for good if he’s pinch-hit for). Bradley’s triple, however, did get me thinking about how many memorable hits by pitchers there have been in post-season play.

If you want a long list of such blasts as evidence the DH rule should be discarded, you’ll be displeased to know that pitchers’ performances in the postseason do not make for a compelling case. I don’t have a lifetime figure for how pitchers as a whole have fared since 1903 (perhaps one has never been compiled), but generally they’ve done pretty poorly — more so since the DH has been instituted, and less pitchers bat less frequently in the majors (or at any level). But I did think of about a dozen memorable instances in which hits by hurlers have been surprising or important, albeit virtually all in World Series competition. We can start with the most famously good-hitting pitcher of all: Babe Ruth.

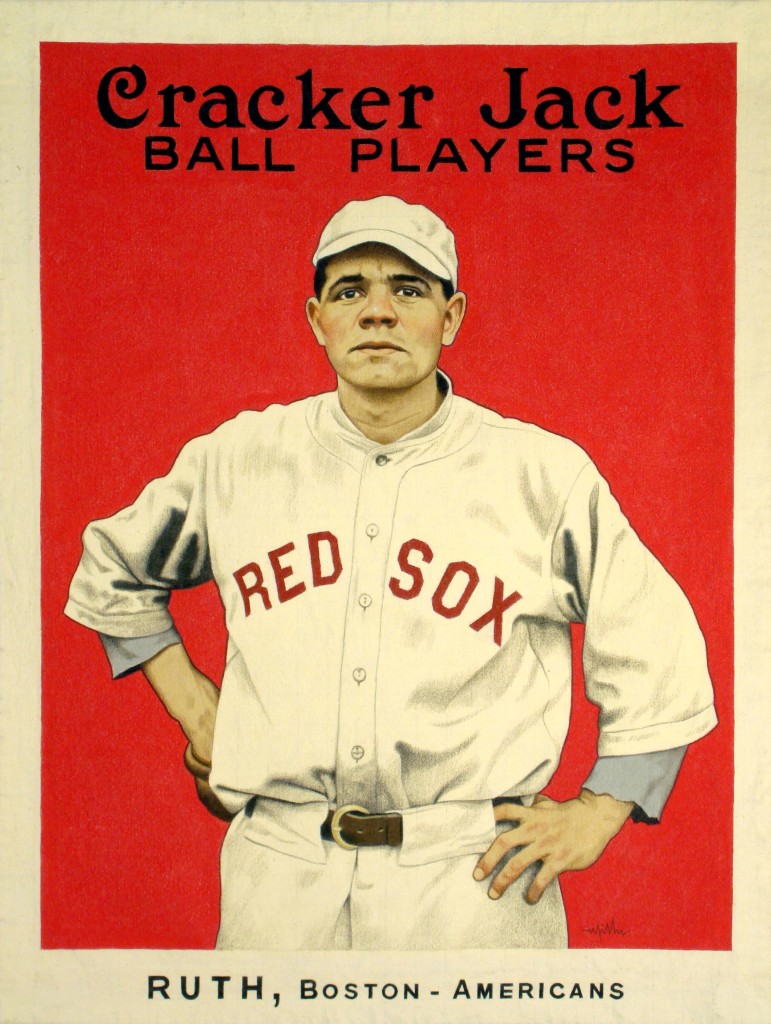

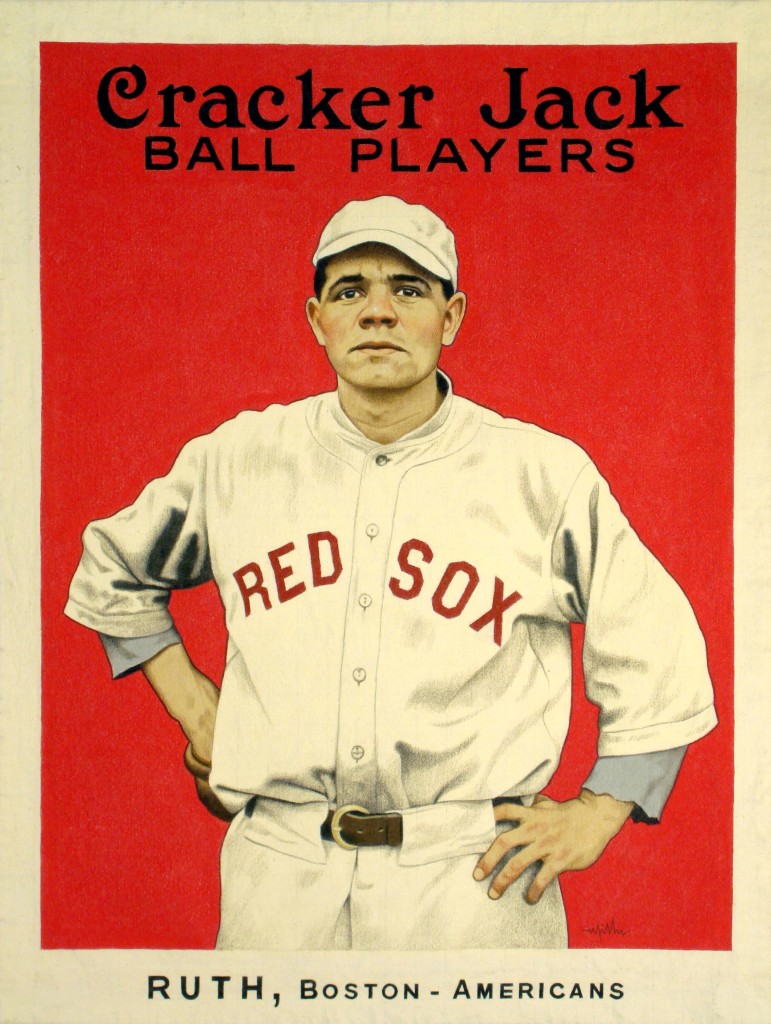

Primarily a pitcher in his first four years in the majors, Ruth was already considered a good enough hitter in his first full season that he pinch-hit in the 1915 World Series. In fact, that was his only appearance in the series, though he’d won 18 games in the regular season. By 1918, he was splitting time between the mound and the outfield (as well as some first base), as it became evident that he had unprecedented power at the plate.

In the 1918 World Series, however, he appeared mostly as a pitcher, starting and winning two games (though he pinch-hit in another). He only had one hit in his five at-bats, but it was a big one — a two-run triple to deep right-center field that proved the margin of difference in his 3-2 victory over the Cubs.

Ruth would play in seven more Series, all as an outfielder for the Yankees. He actually got off to a slow start as a hitter in these, getting injured in the 1921 Series and hitting .118 the next year. But then he asserted himself as one of the best postseason sluggers (in an era when the only postseason games were the World Series, of course), ending up with fifteen homeruns and a .326 average.

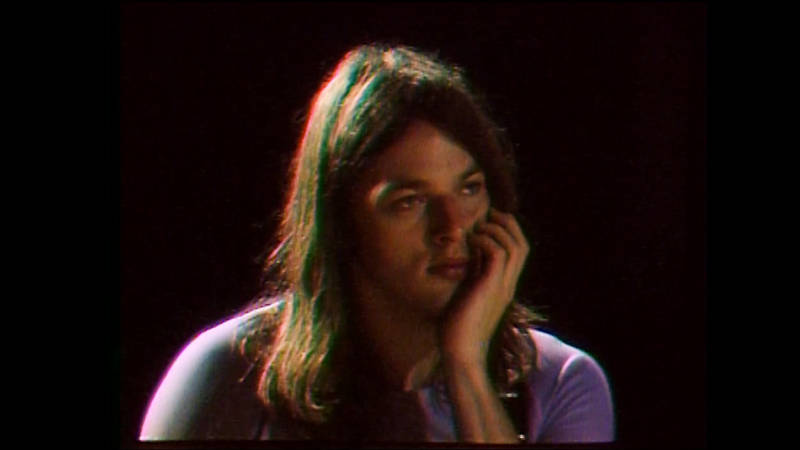

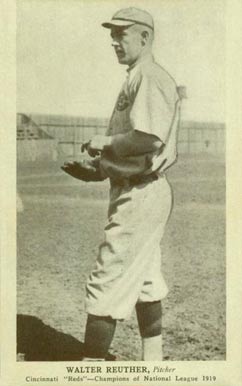

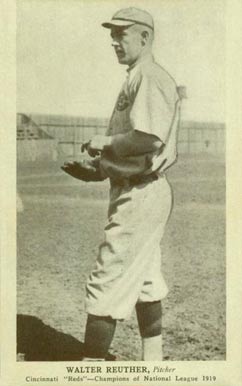

If any World Series hitting feat by a pitcher deserves an asterisk, it’s probably the one in the opener of next year’s series. Won 9-1 by the Reds over the White Sox, this was of course the infamous series in which much of the Sox team threw games for money. In that opener, winning pitcher Dutch Ruether hit not one, but two triples, as well as a single (and walking once), knocking in three runs. His hits are among many plays cited in retrospect as evidence that many of the Sox were deliberately losing, including that day’s opening pitcher, Eddie Cicotte. It’s interesting to note, however, that one of the triples was tagged off a mop-up reliever not involved in the fix, Grover Lowdermilk.

Ruether is probably best known as one of the pitchers on the fabled 1927 Yankees, for whom he went 13-6 in his final year (though he didn’t appear in the World Series). He was a good-hitting pitcher (though no Babe Ruth), with a lifetime .258 average and seven home runs, and an ace on the Reds that year, winning nineteen games and losing six. It’s sometimes overlooked that the Reds were a very good team in 1919, going 96-44 in a season shortened to 140 games in the year after World War I. It’s probable that the series would have been very competitive had the Sox played it straight, but we’ll never know.

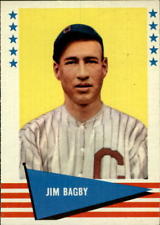

This was a good stretch for Series hitting by pitchers, as in 1920, the Indians’ Jim Bagby clubbed the first homer by a pitcher in series history. This was about as interesting as an 8-1 game can get, as it also saw the first World Series grand slam, hit by Elmer Smith right after the bases loaded with no outs in the first inning. It’s most famous, however, for the unassisted triple play by Indians second baseman Bill Wambsganss later in the contest — a rare play in any game, let alone in the World Series.

It was a capper on a great year for Bagby, who won 31 games in the regular season. He was a fair but not great-hitting pitcher, with a lifetime .218 average, and just two homers outside of World Series play (though he’d been pretty good at the plate in 1920, hitting .252 with eleven extra-base hits in 131 at-bats).

Wrote Bill James in The Baseball Book 1992, for the series game in which Bagby homered (the fifth, in a series the Indians went on to win), “In order to increase attendance, [Cleveland] owner Jim Dunn had shrunk the field of play by installing temporary bleachers in center and right field. When manager Tris Speaker warned Bagby before the game to pitch with extra care to the Dodger home run threats, he replied, ‘Ah think ah’ll bust one out to those wooden seats. They seem just about right for me to hit.’ In the fourth inning, with two men on, Bagby was as good as his word, sending a fly to right center that barely made the bleachers.”

Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean is known more both for his pitching and his overall zaniness than his hitting, but he wasn’t bad with the bat, hitting .225 with eight homers. In his only World Series in 1934, he went three-for-twelve with a couple doubles (besides winning a couple games on the mound). Two of those hits, and one of those doubles, came in one inning in the seventh game — a seven-run inning that broke open the game, won by the Cardinals 11-0.

Facing elimination in the sixth game of the 1940 World Series, the Reds shut out the Tigers 4-0 behind Bucky Walters, who also homered and drove in two runs. In winning the second game 5-3, Walters had doubled and scored. The Reds won the series, and it’s not an exaggeration to speculate they might not have without Walters on the mound and at the plate. It wasn’t a secret, but Walters did have an advantage over most other pitchers: he’d actually started his major league career as a poor-hitting third baseman, switching to pitching after a few years, at which he excelled, winning almost 200 games. That changed him from a bad-hitting infielder to a good-hitting pitcher, ending his career with a .243 average and 23 homers.

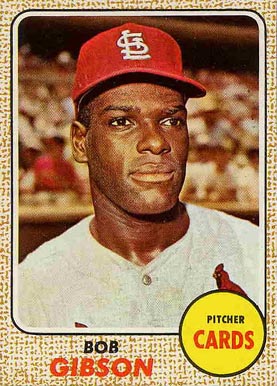

Jumping ahead to 1967, that year’s World Series had two home runs by pitchers. The first was a shocker: Red Sox hurler Jose Santiago, who hit .173 lifetime with just one homer, cleared the fences off Cardinals Hall of Famer Bob Gibson in the opener. It tied the game 1-1, the Cards pullng the game out 2-1. Besides being a much better pitcher than Santiago, Gibson was a much better hitter, with 24 lifetime home runs. And he homered off Red Sox ace Jim Lonborg in the deciding game seven, in his third win of the series.

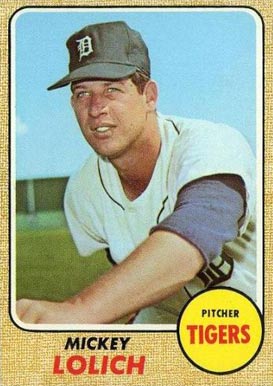

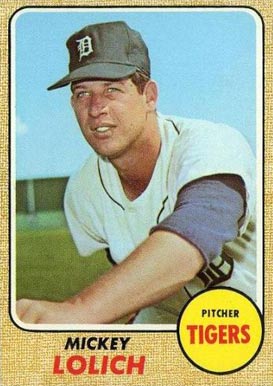

Gibson also homered in the 1968 series, making him the first player to hit two World Series homers as a pitcher. (Oddly, he didn’t homer in either the 1967 or 1968 regular season.) But the unlikeliest homer in World Series history, perhaps, belonged to the opposite team that year. Mickey Lolich, a poor hitter with a lifetime .110 average, belted his only major league home run off Nelson Briles while winning the second game 8-1. He’d also win the seventh and final game of the series for the Tigers (his third win of the series), outdueling Gibson, though neither pitcher homered in that game.

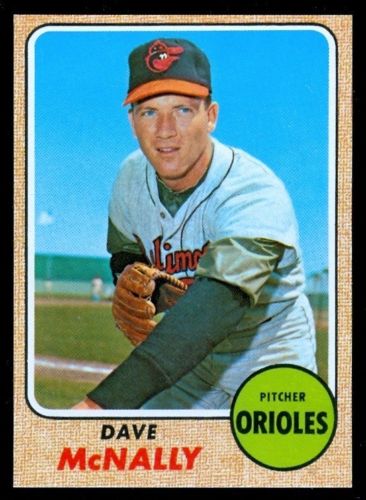

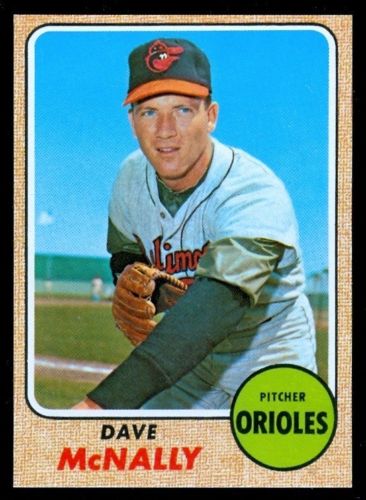

It took just a couple more years for Dave McNally to become the second pitcher to homer more than once in World Series play. He did his bit to try to spoil the Mets’ upset victory over the Orioles by hitting a roundtripper in the fifth and final game in 1969. In 1970, he hit the only grand slam by a pitcher in the World Seres against the Reds in a game he won, and a series the Orioles won. McNally actually wasn’t very good at the plate, with a .133 lifetime average, though he did manage nine home runs. In the 1973 and 1974 postseason, he wouldn’t even get a chance to bat, the DH having been instituted in the American League (including in the championship series, which the Orioles reached in both of those years, though they lost both).

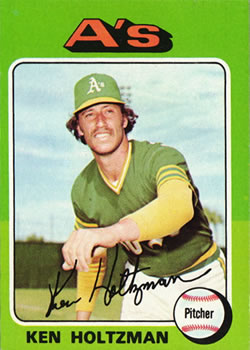

Pitchers could still bat in the World Series, however — in fact, they were required to between 1973 and 1975, before the World Series began permitting DH action (soon to be limited to National League home games in those contests). The team that beat the Orioles in 1973 and 1974, the A’s, benefited greatly from that requirement, even though their pitchers hadn’t batted at all before advancing to the World Series.

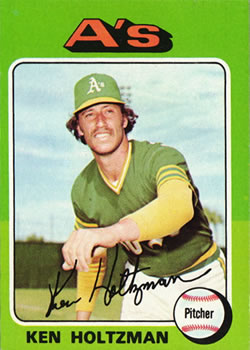

For in 1973, A’s pitcher Ken Holtzman hit two doubles and scored two runs in three at-bats. In the A’s win in the 2-1 opener, one of those runs he scored was crucial. He also scored the opening run in winning the seventh game. The next year, he did even better, homering and doubling in four at-bats (and walking once). supplying key hits and runs in two of the A’s four victories over the Dodgers. Holtzman actually wasn’t that great a hitter even for a pitcher (.163 lifetime average, two regular season homers), but the A’s were sure glad he was there when they needed him.

In that way, Holtzman was sort of a poster guy for advocates of banning the DH. So you think he might have personally objected to the DH rule, right? No. “I personally like the DH because it enabled me to stay in the game longer and not be pinch hit for,” he told Dan Epstein in a 2016 interview for the Jewish Baseball Museum website. “I never wanted to be taken out of a game, regardless of the score or situation, and the DH enabled me to pitch more innings, even though I would have to face one more tough hitter in a line-up than existed in the National League.”

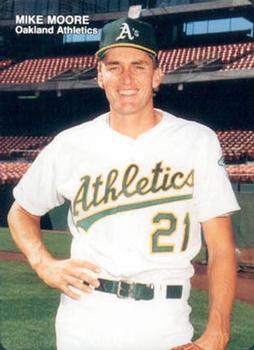

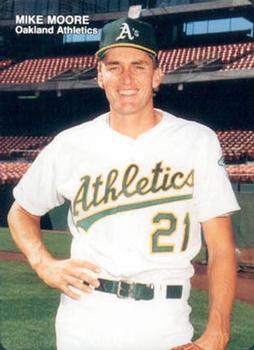

An A’s pitcher also struck a key blow for their final World Series title to date, though it doesn’t seem as well remembered as many of the other feats on this list. In the fourth game of their 1989 sweep of the Giants, winning moundsman Mike Moore struck a two-run double. Having spent his whole career in the American League, Moore had batted exactly once in the majors before the series (and would never bat in the majors after this game, spending the rest of his days in the AL too). The A’s needed those two runs, too, as the final score was 9-6. The actual baseball of the 1989 World Series, however, tends not to be remembered too well, overshadowed by the earthquake that interrupted the series after the first couple games.

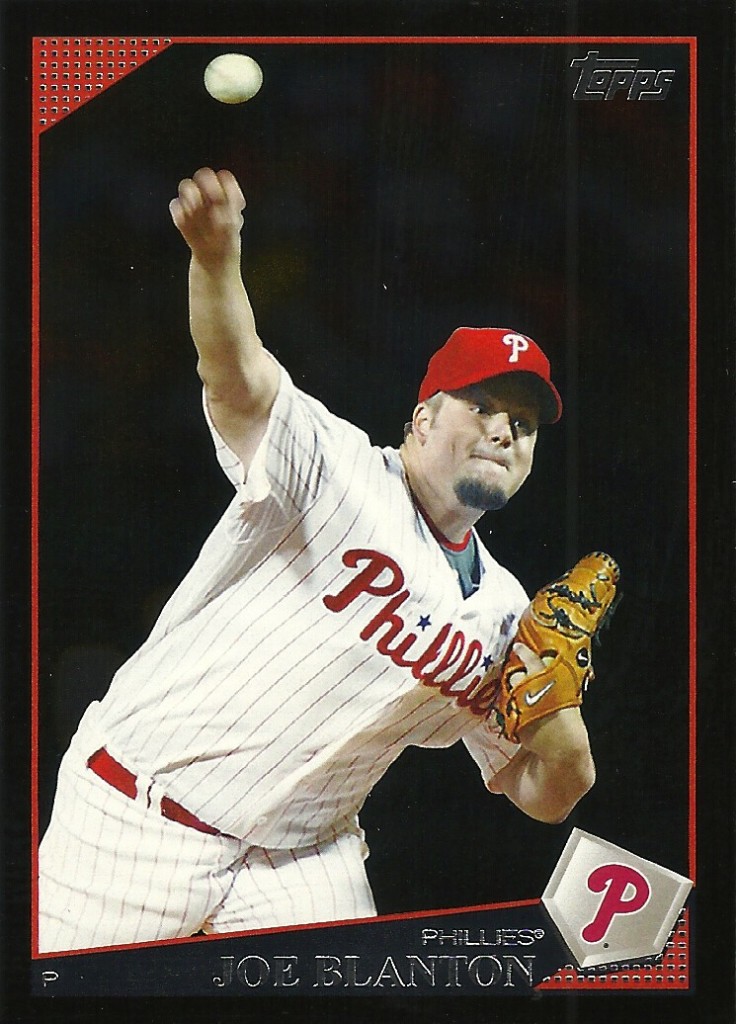

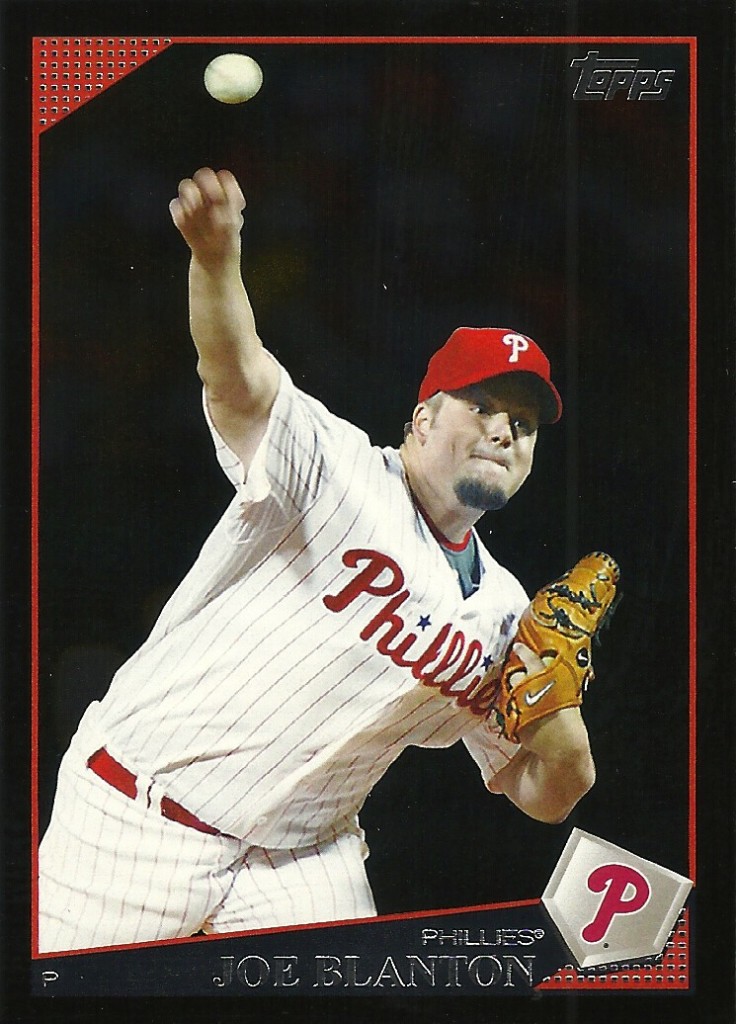

Jump ahead almost twenty years, and we have the only pitcher besides Mickey Lolich to strike his only major league home run in World Series play. Joe Blanton of the Phillies did so as the winner of a 10-2 blowout over the Rays in 2008. If Lolich was a bad hitter, Blanton was even worse, hitting .106 with no extra base hits in 216 career at-bats (and 92 strikeouts). Lolich did at least have five doubles and two triples, albeit over a longer career.

Asked at the time when he’d last hit a homer at any level, Blanton guessed it was high school. “I’m not a hitter,” he admitted. “I’m just going to close my eyes and swing as hard as I can, just in case I make contact.”

Blanton and Lolich are the only pitchers to have hit their only major league homers in the World Series, but another deserves honorable mention, to break up the chronological flow of this post just once. Don Gullett’s homer in his opening win over the Pirates in the 1975 National League championship series was his only such major league blast. The Reds pitcher also singled in that game, driving in three runs in all. He actually wasn’t so bad at the dish, hitting .194 for his career, though without a four-bagger in regular season play.

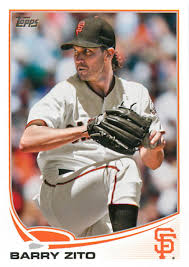

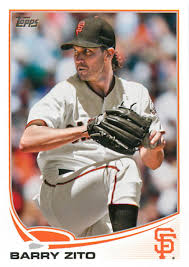

Barry Zito had seldom batted in the regular season before starting a highly-paid and largely disappointing seven-year stint with the Giants. He was a legendarily bad hitter, chalking up a lifetime .102 mark with no extra base hits, though he did at least conscientiously work to improve his bunting during his time in the National League. You had the sense he even had trouble reaching the outfield on the fly, but he did come up with a surprise RBI single against superstar Justin Verlander in his opening win over the Tigers in the 2012 World Series. He’d also driven in a run with a bunt single in his Game Five win against the Cardinals a few days earlier, in a key contest where the Giants were facing elimination.

Often reviled during his struggles with the Giants, those hits — and those wins, in his one fairly good year with the team — were enough to justify that big contract, at least to serious Giants fans. Are they enough to justify getting rid of the DH rule? That’s up for debate, but those occasional blows pitchers strike in the games that matter most do matter.