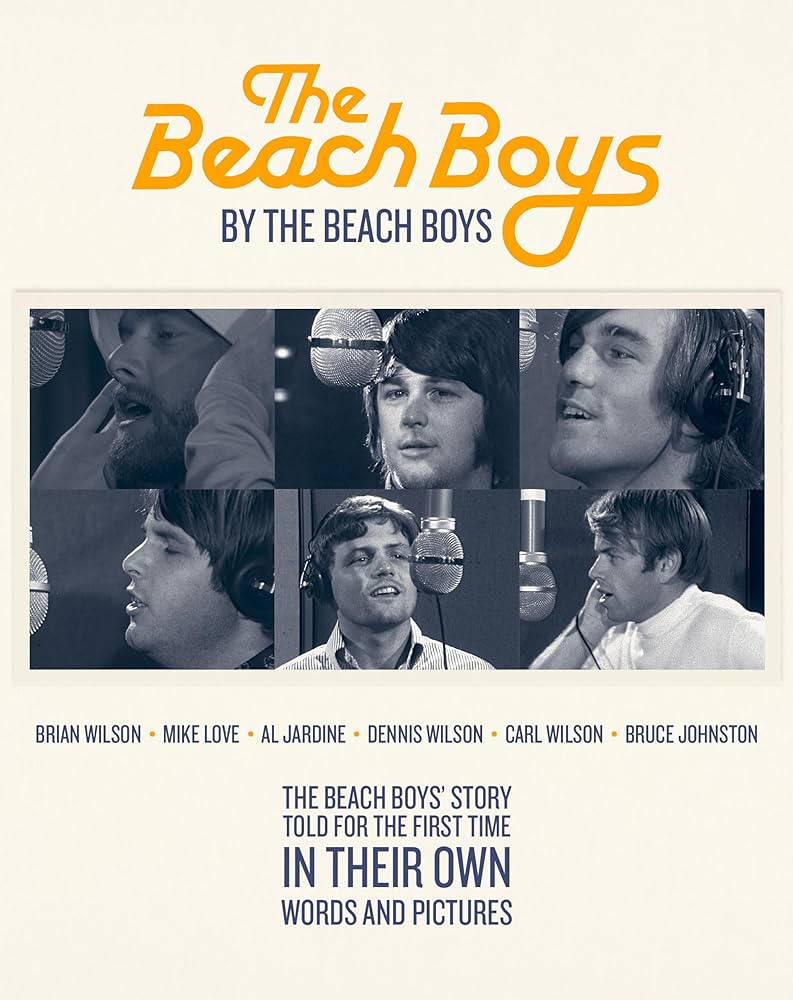

The Beach Boys By the Beach Boys, just issued by Genesis Publications, is sort of like what Anthology was for the Beatles. It’s an oral history where all of the principal Beach Boys (the six that played together on Pet Sounds, for easy reference), some of the others who were members for a while, and some people from outside the band talk about the group’s history. The great majority of the comments are from the six core Beach Boys—Brian Wilson, Carl Wilson, Dennis Wilson, Mike Love, Al Jardine, and Bruce Johnston—though obviously the late Carl and Dennis didn’t directly participate in the book’s production, with many quotes taken from archival sources.

This isn’t quite up to the level of the Beatles’ Anthology in depth, visuals, and candor, but it’s still pretty interesting, even if you know a lot about the group and some of the stories are inevitably familiar. Fortunately, it cuts off at 1980, eliminating the lengthy later period in which they only sporadically put out music. There are tons of pictures, again running the gamut from familiar to rare, and some non-photo memorabilia. Perhaps unsurprisingly, a number of controversial parts of the story (such as Dennis Wilson’s friendship with the Manson Family) are not mentioned or referred to only briefly.

This post isn’t a review of the book, which I’ll have in my year-end roundup of rock books. Instead, I’ll go over some of the more surprising inclusions and comments. These are all from the pre-1967 era, as I’m not too much of a fan of their post-Smile work, acknowledging there are plenty of Beach Boys fans who hold a different view.

1. For me, the very most surprising illustration shows a couple pages from a Brian Wilson notebook with his handwritten lyrics for “Surfer Girl.” What could be so surprising about lyrics to a familiar hit song, you’re thinking. Well, the lyrics are entirely different from the record. Not just a few words crossed out and substituted here and there; entirely different. What’s more, it’s titled “Surfer Girl (Fast),” and the Beach Boys’ hit “Surfer Girl” is definitely not fast; it’s a slow ballad. The words in this version strike an entirely different mood than the hit single lyrics, too, with a more ebullient scenario about meeting the surfer girl at a party and how she’s a “livin’ doll.”

So – could Brian have first conceived of a song about a surfer girl that was absolutely different both musically and lyrically, and then junked it and started from scratch, just keeping the title and some general themes about taking her surfing? Frustratingly, the book doesn’t say. It just notes the illustration is of lyrics for “Surfer Girl” from Brian’s notebook, as if the caption writer isn’t at all familiar with the hit version.

2. Al Jardine remembers hearing the Beatles for the first time when the Beach Boys were on tour in New Zealand and “I Want to Hold Your Hand” came over the radio. “I thought it sounded raw and live,” he comments. “It sounded like a live recording, which it probably was, because they played live in the studio unlike us.” I found this reaction unusual, because although “I Want to Hold Your Hand” certainly bursts with energy, I’ve never thought of it as especially raw. Not like, say, the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie,” which became a US hit just a few weeks before “I Want to Hold Your Hand” did.

As for it being a live recording, even back in late 1963, the Beatles were sometimes using multi-tracking, overdubbing, and edits. In his big Rolling Stone interview in the early 1970s, John Lennon said “the first set of tricks was double tracking on the second album…We’d double tracked ourselves off the album on the second album. Not really.” As it happens, the October 17, 1963 session when “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was recorded was their first with four-track recording equipment. Mark Lewisohn’s The Beatles Recording Sessions doesn’t note overdubs for this track, but I’m guessing the handclaps might well have been, and perhaps there was some vocal double tracking.

There’s not a right or wrong in Jardine’s initial perception of the track, and I’m not annoyed by it. It’s just not one I’ve heard others express.

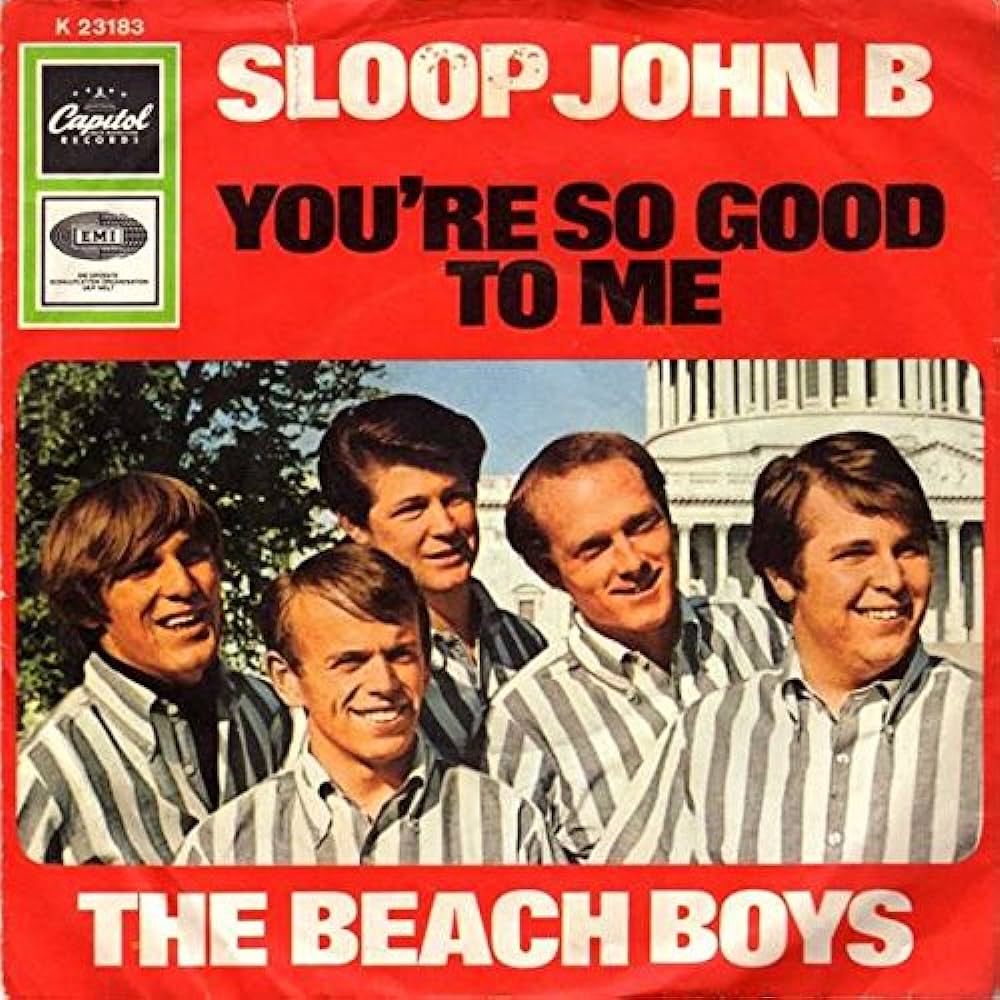

3. Speaking of Al Jardine, there’s a surprising note in the introduction to the 1964 chapter: “It needs to be noted that in the early years Al Jardine was the Beach Boys’ hidden studio bassist, handling four-string duties on such instant classics as ‘Fun Fun Fun,’ ‘Catch a Wave,’ ‘Hawaii,’ ‘Little Saint Nick,’ ‘Don’t Worry Baby,’ “I Go Around,’ ‘All Summer Long,’ ‘Hushabye,’ ‘Little Honda,’ ‘Wendy,’ ‘Girls on the Beach,’ ‘Don’t Back Down,’ ‘She Knows Me Too Well,’ ‘You’re So Good to Me,’ and others.”

Al Jardine is, for most fans, the least colorful of the five primary Beach Boys (Bruce Johnston, who came aboard in 1965, didn’t play on as many records or concerts). He’s mostly known as the rhythm guitarist, a harmony singer, and occasional lead singer (most famously on “Help Me, Rhonda”). That’s a lot of songs on which he is reported in the book to have played bass, and it doesn’t even list all of them. The paragraph also doesn’t mention he played standup acoustic bass on their first single, “Surfin’.”

This isn’t amplified in the book, but if he played bass so often in the studio, he was an underrated contributor, at least to this early work. It also isn’t examined why Brian Wilson, who was publicly known as the band’s bass guitarist through the mid-1960s, would have had Jardine play on so many recordings. Here are just a couple guesses. Maybe Brian wanted to focus on producing as much as possible, and was content to leave the bass duties to Jardine on some songs. Or maybe they both played bass on at least some of the records, fattening the sound with multi-tracking.

4. And while we’re on the subject of bass guitar, for all of Brian Wilson’s multifaceted talents, his bass playing doesn’t get discussed too much in general. He’s most known as a composer, singer, and producer, and not so much as an instrumentalist, especially as he sometimes had non-Beach Boy session musicians play on some of the group’s most notable records. When his instrumental performances are thought of, what he does as a keyboard player comes to mind more than what he plays on bass.

But Brian does have some detailed comments about the bass and its role on Beach Boys records in the book. On “Here Today” from Pet Sounds, “I wanted to present the idea of a bass guitar playing about an octave higher showcased as the principal instrument in the track.” Pet Sounds itself, he notes, “was a great album for its basslines, and I think people picked up on that. It taught bass players a way to be more creative.”

Carl Wilson also has a detailed comment about bass parts from this era. Brian, he says, “was writing basslines that were so far from the norm. ‘God Only Knows’ is the classic example that takes it to a new plateau. The bass was played in a different way from the one in which the song was written. It was inverted. ‘Sloop John B’ also had a brilliant bassline, the kind of line that musicians really loved.”

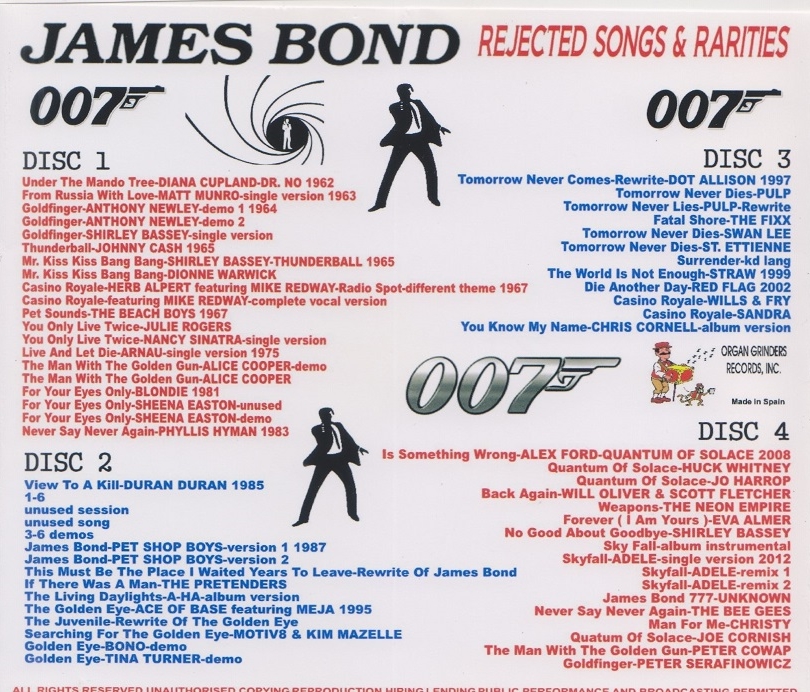

5. I don’t remember hearing that the instrumental title track to Pet Sounds was intended as a James Bond theme from the time I started reading extensively about the Beach Boys in the late ‘70s. It seems to be more commonly known now, and you can hear how it could have fit into a Bond movie as a theme or a song for certain scenes, though apparently it didn’t get into the running. Here’s a Brian Wilson comment on it from the book:

“It was originally titled ‘Run, James, Run!’ It was supposed to be a James Bond-themed song. We were going to try to get it to the James Bond people, but we thought it would never happen, so we put it on the album.”

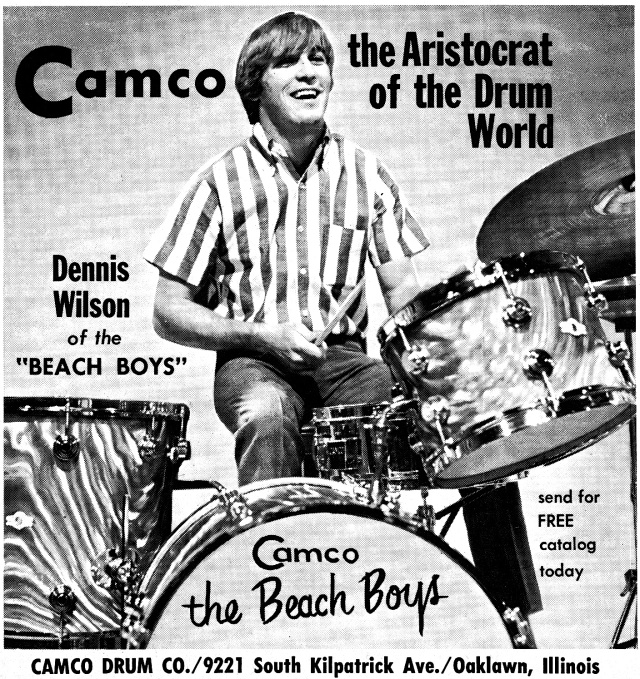

6. Dennis Wilson is often, maybe usually, assumed to be a mediocre drummer, and one who’d rather be at the beach than at the studio, leading to the use of session musicians like Hal Blaine on Beach Boys sessions to play drums on their records. Carl Wilson has an interesting comment to the contrary: “Brian liked to use Hal because Hal was more reliable than Dennis, but whenever Dennis got the chance to play, he always did a great job. He played drums on more of our records than most people realize. I think because he didn’t play on Pet Sounds everybody assumes he never played at all, and that’s just not the case.”

Somewhat contradictorily, a quote from Dennis reads: “If you listen closely to the Pet Sounds album, you’ll hear me playing jazz patterns. Not everything was rock and roll.” The contradiction isn’t Wilson saying some of the patterns was jazzy, but that he actually played them. Did he play on Pet Sounds or not? Or maybe just some parts, or some parts that weren’t used? I don’t think the answers will ever be final.

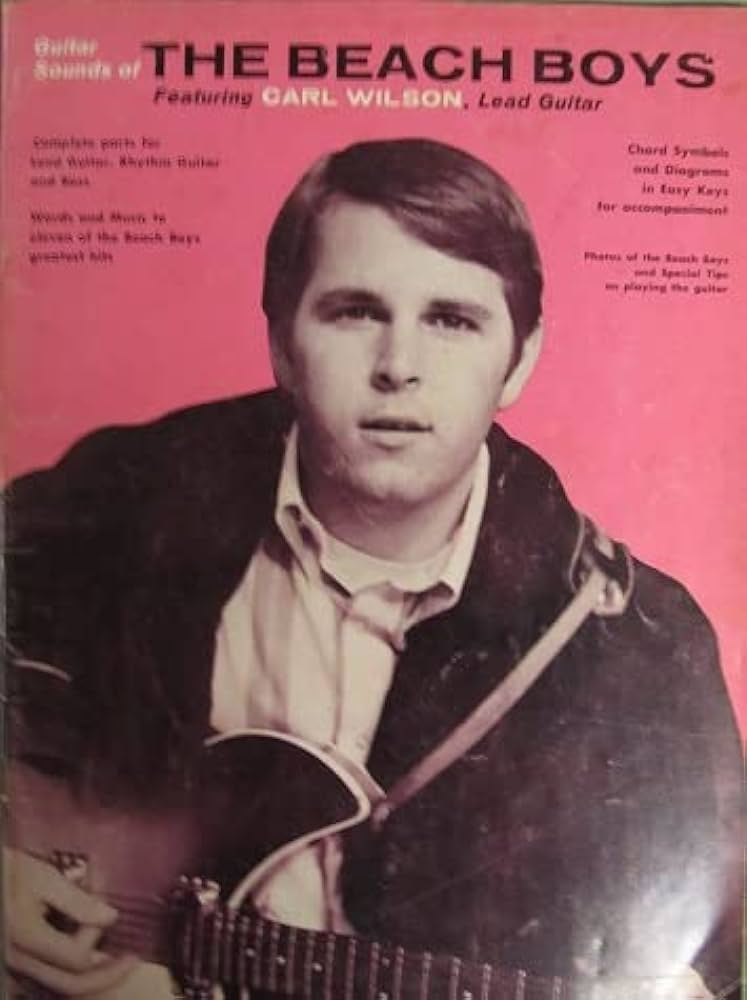

7. Carl Wilson was the most skilled instrumentalist in the Beach Boys, aside perhaps from his older brother Brian. You don’t hear much of his trademark crisp guitar style on Pet Sounds, and I’ve wondered exactly how much he managed to get on, and whether it bugged him that his contribution on guitar was probably less on this album than any other. Here’s how he’s quoted in the book:

“I didn’t play that much guitar on the Pet Sounds sessions, although I do remember playing 12-string direct through the board. My playing wasn’t as consequential as it had been before and would become later, because everything had become more of an orchestra, part of the whole. It wasn’t that simple form, like our early records, with a little song and little lead break and drive home the chorus. It was more symphonic.”

8. Not to pick on Al Jardine too much, but he didn’t seem to have too much input into the group’s overall direction, especially before he started getting some of his compositions on records. An exception was “Sloop John B.” When Jardine’s specific contributions to the Beach Boys are cited, it’s usually noted that he was the folk music fan in the group, and was the main force behind them interpreting some folk material, most famously “Sloop John B.” This folk song had most famously been done by the Kingston Trio, an influence not only on Al, but also on the visual image of the group, who wore similar striped shirts in concert in their early years.

So why didn’t he sing lead on the hit single version of “Sloop John B”? There’s a pretty long and interesting behind-the-scenes account from Al in the book:

“A year before we cut it, I told Brian if it was performed in our style, he might enjoy it. I sat and played these chord progressions, basically three chords done on guitar, banjo and keyboards. I knew I had to have keyboards, otherwise I wouldn’t get his attention. I took a pretty primitive folk song, which I’d learned in high school, and added a chord or two—I heard the Beach Boys harmonies in there and felt very strongly that we could make a great record.

“The very next day, I got a phone call to come down to the studio. Brian played the song for me and I was blown away. From concept to the completed track took less than 24 hours. He then lined us up one at a time to try out for the lead vocal. I had naturally assumed I would sing the lead, since I had brought in the arrangement. It was like interviewing for a job. Pretty funny. He didn’t like any of us. My vocal had a much more mellow approach because I was bringing it from the folk idiom. For the radio, we needed a more rock approach. Brian and Mike ended up singing it. But I had a lot of fun bringing the idea to the band.”

“Sloop John B,” a #3 hit single in the US and #2 in the UK, is sometimes knocked for not fitting into Pet Sounds, or diluting the concept, or being a commercial concession to Capitol Records. Jardine has a different view that’s refreshing, if not to the liking of some purists. “The label said we needed a hit single on Pet Sounds, something with some commercial appeal. ‘Sloop John B’ had proved itself. It may not fit the creative tone of the album, but it certainly gave some relief at the end of side one.”

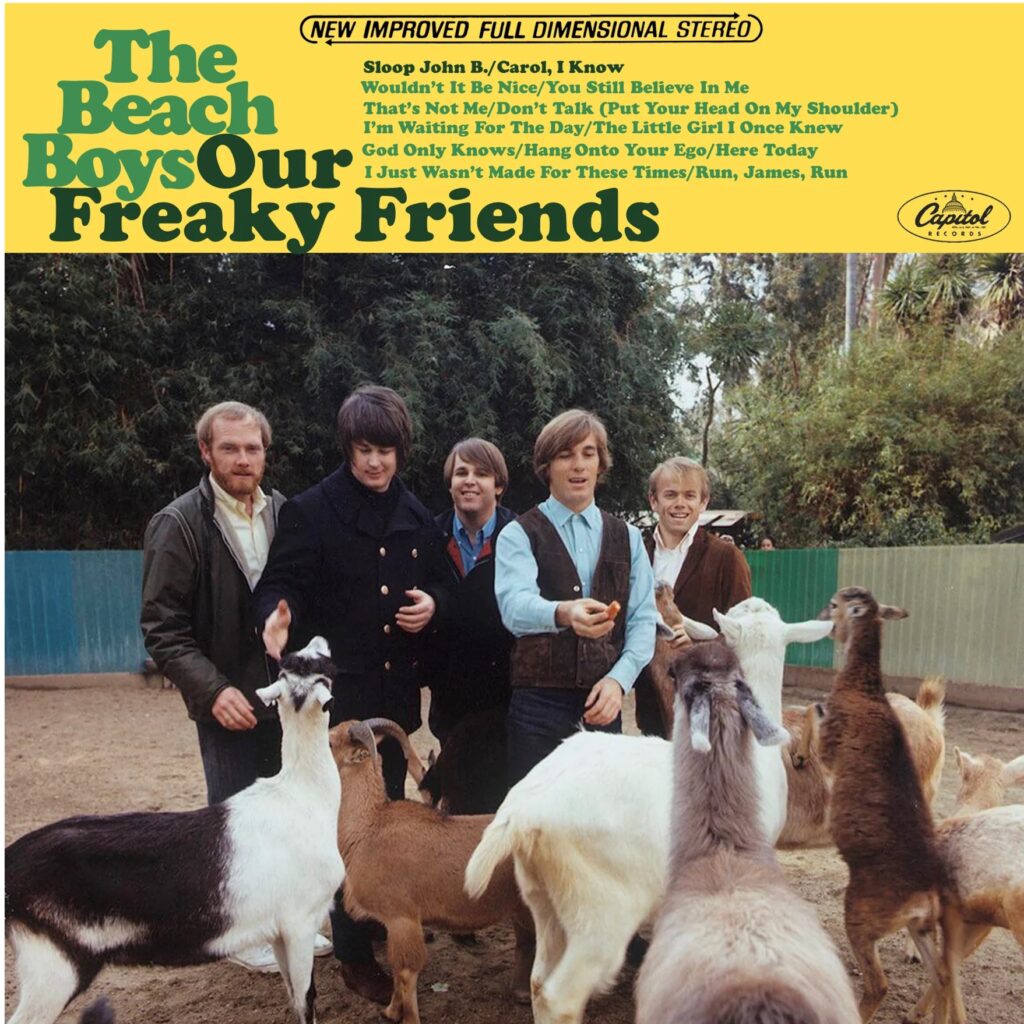

9. Ever wonder why the cover of Pet Sounds shows the Beach Boys in a zoo (the San Diego Zoo)? Maybe I’ve read this previously and missed it, but Mike Love tells it this way:

Capitol’s “working title for the album had been Our Freaky Friends. To illustrate that cover, Capitol had sent us to the San Diego petting zoo to photograph us with our new ‘freaky friends’—the animals. When the LP was renamed Pet Sounds, Capitol reviewed the pictures from that same photoshoot and selected an image of us feeding a bunch of hungry goats. Not exactly inspired artwork, but indicative of Capitol’s creative efforts.”

I’m teaching a seven-week non-credit course on the Beach Boys from June 18-July 30 at the College of Marin in Kentfield, CA. It will meet on Tuesday nights from 7:10pm-9:30pm, and can be taken both in-person and through Zoom. Concentrating on their best work in the 1960s, the course follows their growth from their early surf and hot rod anthems through their lyrical maturation with symphonic masterpieces like “Good Vibrations” and the Pet Sounds album. Besides exploring leader Brian Wilson’s phenomenal skills as a melodic composer and sophisticated studio producer, the group’s glorious vocal harmonies will also be highlighted through a wealth of audiovisual clips and instructor commentary. Registration info at https://marincommunityed.augusoft.net, for course #8221M/6361.