Sometimes it seems like everything’s been reissued on CD, even those rare Dutch-only B-sides, tracks from stray French EPs, and live Japanese albums. Some cuts you might think you’ve never seen on reissues turn up in odd places if you look hard enough. Steve Miller’s early non-LP single “Sittin’ in Circles” is a bonus track on a UK 2012 CD reissue of his Children of the Future album; Bob Dylan’s live Liverpool 1966 B-side version of “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” was on the Japan/New Zealand/Australia-only 1978 triple LP Masterpieces (and then part of the mammoth recent box The 1966 Live Recordings); the Grateful Dead’s short 1968 single version of “Dark Star” is on the box The Golden Road (1965-1973)as a hidden bonus track on the Live/Dead disc (and then part of the various-artists box Love Is the Song We Sing: San Francisco Nuggets1965-1970). Joni Mitchell’s non-LP 1972 B-side “Urge for Going” is on her 1996 compilation Hits, even though it wasn’t one.

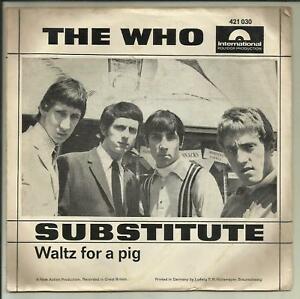

It gets goofier than that in some cases. The instrumental “Waltz for a Pig” was used as a B-side for the Who’s “Substitute” in 1966, though the UK release credited it to “the Who Orchestra” since it wasn’t actually the Who. (Short explanation: the Who could not record until a court case with producer Shel Talmy had been settled.) It did come out in 2012 on CD — but not on a Who CD. Instead, it was on the Graham Bond Organization box set Wade in the Water. That’s because the Who Orchestra were a pseudonym for Graham Bond’s group, who cut the quite good soul-jazz-rock instrumental with Ginger Baker (now credited as the composer) on drums. Even before that, it had made it onto the 1968 Japanese LP compilation Exciting the Who. Got all that?

And of course there have been vaults full of previously unreleased material, sometimes enough to fill box sets, as my previous posts on expanded editions have noted. Is there anything left, even if you limit yourself mostly to the 1960s, the era in which I’m most expert?

Statistically, most vinyl releases have never been reissued on CD. You might find that hard to believe when you struggle to find enough shelf space for your compact discs. But keep in mind that most records don’t sell very well, and many of them — maybe most — aren’t very good. Yet even leaving aside the countless acts who only made one or two singles not worth bothering about, are there any — let alone many — officially released tracks by ‘60s notables that have seldom or never been reissued?

Even casting aside marginally different stereo/mono issues and mixes, there are still a good number of such items. Why they’ve rarely or never been cleared for reissue is usually a mystery the likes of us mere fans aren’t given clues to, leaving the motives of the labels and/or artists up for speculation. On occasion it’s pretty apparent why a certain cut isn’t available; sometimes it’s widely rumored an artist is ashamed of the music and blocking its re-release; and other times, the reasoning is inexplicable.

In the post, I’ll go through a dozen or so of my favorite examples. No doubt readers know about some that haven’t come to mind, or just aren’t tracks I care about much. It’s entirely possible that some of these have actually been reissued on discs I’m not aware of, in which cases corrections are gratefully received.

Bob Seger, “2+2+?” (Capitol 45 version).The original version of this oddly titled tune, as heard on a 1968 Capitol single, has never been reissued in any format as far as I know. That’s a crime, as it’s not only Seger’s greatest recording, but also one of the rawest, most powerful anti-war rockers of all.

But wasn’t that on his Ramblin’ Gamblin’ Man LP, you’re asking — an album that’s pretty easy to find used and cheap? Yes, but the seven-inch version simply destroys the tamer LP counterpart. And that’s not just collector talk that builds up cuts for their sheer rarity. The single has a searing intensity that couldn’t be matched, making the rationale behind a fairly limp album variation a mystery of its own.

Seger, as many of you likely know, seems to take an inordinate lack of pride in his earliest sides, though these are precisely the ones that will appeal most to garage rock enthusiasts. It was enough of a surprise that approval was finally granted for a CD compilation of his 1966-67 singles on ABKCO last year (the heartily recommended Heavy Music). What’s blocking the original 45 take of “2+2=?” is uncertain, not to mention unfathomable.

Update: So after all that grandstanding with my pick to lead off this list, soon after posting it, a reader informed me the Capitol 45 version was reissued a couple years ago as a vinyl seven-inch by Third Man Records. Backed by “Ivory,” it’s out of stock at the moment. Yet it might not be the exact same version as you hear on the original single. As another reader wrote, “The 45cat.com site says this this Third Man reissue is in stereo and not the original mono 45 mix.”

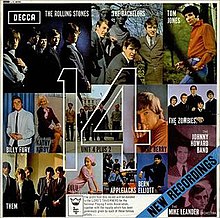

Them, “Little Girl” (uncensored version). For decades, it was impossible to collect all of Them’s terrific output with Van Morrison in one place. The three-CD The Complete Them 1964-1967 seemed to finally take care of that — but not quite. For it doesn’t have the notorious alternate version of “Little Girl” (only issued on the first pressing of the obscure 14 various-artists UK charity compilation LP) on which Van yelps an obscenity on the fade. Not just any obscenity a la “damn,” mind you, but the f-word, enunciated clearly enough to leave little doubt as to what Morrison had in mind. Like many of Them’s early efforts, “Little Girl” was an outstanding gritty R&B/rocker—but to hear this variant, you’ll have to resort to bootlegs, unless you can track down a rare first pressing of that 14 LP.

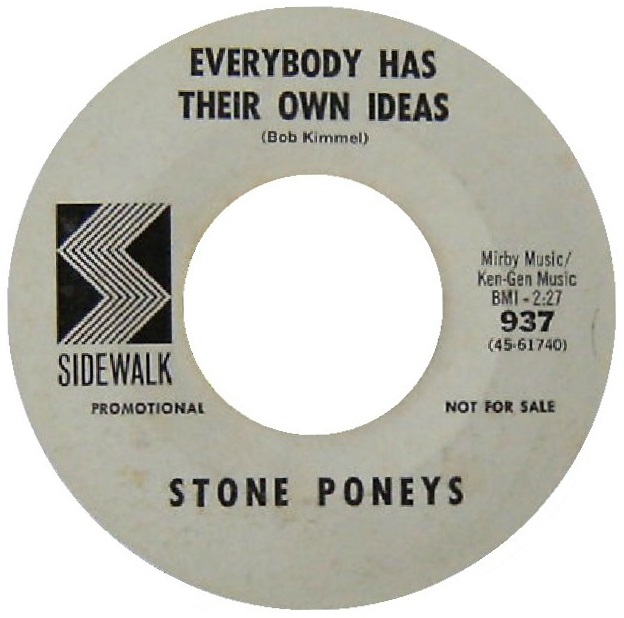

The Stone Poneys, “So Fine”/”Everybody Has Their Own Ideas” and “Carnival Bear.” Linda Ronstadt became a superstar, and even everything by her first group, who only had one hit, has been reissued—and available on CD for a long time. Well, not quite. Again, even Ronstadt fans might not know that before doing three albums for Capitol, the Stone Poneys issued a 1966 single on the small Sidewalk label. Maybe Ronstadt has veto power over whether it gets on compilations, but as her first outing on disc, it makes for an odd omission from her in-print discography.

Of course, like many such hard-to-hear scarcities, it’s not that great, the A-side being a routine cover of the big late-’50s doo wop hit by the Fiestas. The B-side, written by Stone Poney Bob Kimmel, is a little more interesting, as a minor-keyed just-about-folk-rocker that’s a little reminiscent of some efforts in the same direction by Bay Area groups with male-female vocals, like We Five and the Mojo Men.

Oddly, that’s not it for MIA Stone Poneys tracks. “Carnival Bear,” the B-side of their flop 1968 single “Up to My Neck in High Muddy Water” (credited to Linda Ronstadt & the Stone Poneys), has never been reissued either. It’s not that great — in fact, it’s kind of a weird fusion of baroque pop-rock, wistful country, and (in the later section) rather histrionic operatic vocals. I’ve never heard of the composer, non-Stone Poney Chris Howard, who has few credits to his discography. As a bonus should you track down the rare 45, it comes in a picture sleeve that looks like a different shot from the same session that generated the photo on the cover of Linda Ronstadt, Stone Poneys & Friends’ Vol. III LP.

Much better than the aforementioned rarities, incidentally, is the early-’70s non-LP solo Ronstadt B-side “She’s a Very Lovely Woman,” a gender-adjusted cover of the Emitt Rhodes-composed Merry Go Round classic “You’re a Very Lovely Woman.” She even performed it on TV on Andy Williams and Johnny Cash’s shows. This has been reissued once, however, as a bonus track on the 2009 Australian CD two-for-one-disc reissue of her first two solo albums, Hand Sown…Home Grown and Silk Purse (on the Raven label).

Francoise Hardy, “The Bells of Avignon.” Tucked away on a 1970 non-LP UK B-side few Françoise fans have even heard is “The Bells of Avignon,” sung in English and penned by British composer Tony Macaulay. His resume included the Foundations’ “Build Me Up Buttercup,” Edison Lighthouse’s “Love Grows (Where My Rosemary Goes),” Long John Baldry’s “Let the Heartaches Begin,” Scott Walker’s “Lights of Cincinnati,” and the Hollies’ “Sorry Suzanne.”

Cheerier than Hardy’s usual wont, it’s a pleasant enough lyrical jog through memories of the French town honored by the title. It’s kind of hard to picture Hardy as an on-the-road rambler, but that’s the role she takes here, Macaulay making reasonably catchy use of periodic bends into more bittersweet melody. It’s sort of neat how the bridge is quite different from the verses, going into a more uplifting, hopeful, yet yearning mood as she anxiously anticipates a reunion with the Avignon boy she left behind.

As far as I know, “The Bells of Avignon” has never been reissued, making it one of the prime Hardy rarities. It’s not even on the recent 24-track Ace compilation of many of her late-’60s/early-’70s English-language recordings (Midnight Blues: Paris London 1968-1972), an omission that’s odd indeed. It could be argued that Hardy isn’t a notable ‘60s artist to most English-speaking audiences—a superstar in France, she had only sporadic UK success and virtually none in the US. But when someone’s memoir is translated into English and issued by an American publisher, as hers was last year, it could be argued that she’s now risen above cult status Stateside.

Melanie, “Beautiful People”/”God’s Only Daughter” and “Garden in the City”/”Why Didn’t My Mother Tell Me” (1967-68 Columbia singles). To repeat another “even fill-in-the-blank fans don’t know” citation, even many committed Melanie fans don’t know she did a couple singles for Columbia before her debut LP for Buddah. What’s more, the earlier of them has the original version of one of the more popular songs from her early career, “Beautiful People.” Why haven’t these been reissued? Maybe there just wasn’t an obvious place for them, if she only put out four Columbia tracks (and though I like Melanie, I don’t see a four-song EP of her Columbia work as a likely Record Store Day release in the near future). Melanie might want them buried if she has a say in the matter, as she didn’t find her short stay at Columbia a pleasant experience, balking at the poppier direction Clive Davis tried to push her toward.

While this pair of 45s isn’t terrific, they’re okay. “Beautiful People” has an expectedly poppier arrangement than the Buddah remake, though not hugely so. She’d also remake its B-side, “God’s Only Daughter,” for Buddah, and make “Garden in the City” the title track of a 1972 LP, though its B-side, “Why Didn’t My Mother Tell Me,” doesn’t seem to have been revisited elsewhere. Both of the singles, by the way, were arranged by John Abbott, whose most famous credit was Dion’s “Abraham, Martin & John,” and is also of note for working on the sole LP by Montage, the interesting late-’60s baroque-pop-rock group masterminded by former Left Banke mainman Michael Brown.

One good home for these two Melanie singles would be on a release that combined them with some solo acoustic demos from the same period that have surfaced online, albeit from a scratchy acetate. Also added could be obscure pre-debut LP songs she wrote that were covered by the mysterious “Mommy” (either a solo woman artist or a female group) on the 1967 single “Sad Song”/”Love in My Mind,” the latter of which Melanie recorded for her 1972 album Garden in the City. But such a compilation seems unlikely to be assembled in the near future, both because of possible licensing difficulties and an unfortunate lack of industry interest.

Tim Hardin, “Lenny’s Song” (original solo piano version, on 1966 compilation LP Why Did Lenny Bruce Die). “Lenny’s Song” was arguably the finest song Tim Hardin wrote after his first two albums. It appeared on his Live in Concert album, recorded at New York’s Town Hall on April 10, 1968. An arguably more memorable version had appeared back in late 1967, as “Eulogy to Lenny Bruce,” on Nico’s solo debut LP, Chelsea Girl. Few are aware that Hardin had released a yet earlier performance of his composition on the compilation album Why Did Lenny Bruce Die, issued shortly after Bruce’s August 1966 death. While it’s fairly bare compared to the full-band Live in Concert take, it’s an affecting, heartfelt solo piano rendition.

Most of Why Did Lenny Bruce Die is a sort of interview/sound collage tribute to the comedian, and in fact there’s a voiceover narration about Bruce (not by Hardin, I’m pretty sure) for the first minute or so of “Lenny’s Song” as a piano plays in the background. Still, it seems a place should have been found for this as a bonus track on some CD reissue or another. With its failure to appear on Hang on to a Dream: The Verve Recordings, or the Australian two-fer CD of his first two LPs, orthe CD reissue of Live in Concert(all of which have bonus cuts), it seems unlikely it’ll get picked up in the future, possibly because its appearance on the Probe label presents licensing difficulties.

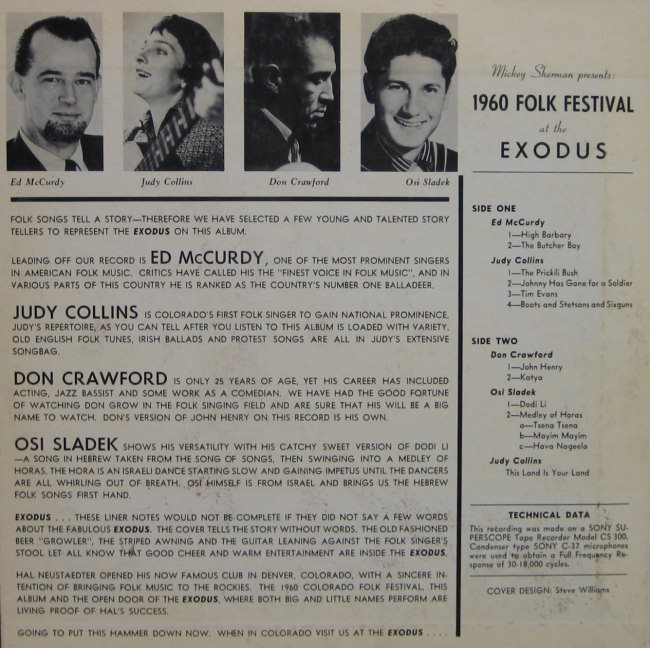

Judy Collins, tracks on Folk Festival at the Exodus and 1960 Folk Festival at the Exodus LPs. Before signing to Elektra Records, the label she spent many years with as a folk and then pop star, Collins had a few tracks on a couple rare local compilation albums, 1959’s Folk Festival at the Exodus and the following year’s similarly titled 1960 Folk Festival at the Exodus. Both were recorded in Denver’s most popular folk club, the Exodus. They’re so rare, in fact, that I still haven’t heard them. I’ve only even seen them a couple times, once in a huge collection of a big collector, and then just late last year as part of an exhibit at the Colorado Music Hall of Fame. The Collins tracks on these LPs have never been reissued, to my knowledge, let alone the albums themselves. When I interviewed her for the liner notes of some CD reissues in 2010, she casually agreed with me that it would be a good idea to make them available again, but I don’t know if she has any official power to do so.

(Note: About a year and a half after writing this post, I was finally able to hear the five Collins tracks from 1960 Folk Festival at the Exodus. They’re very good, strong straight folk performances, about on the level of her 1961 debut LP Maid of Constant Sorrow. In fact, she re-recorded two of the five songs (“Tim Evans” and “The Prickilie Bush”) for that Elektra album. I still haven’t heard her tracks on 1959’s Folk Festival at the Exodus.)

Save the Children: Songs From the Hearts of Women album. Speaking of Collins, she (with Ethel Raim Dunson) produced and coordinated this rare May 1967 compilation LP. As it was on the Women Strike for Peace label, I’m guessing it might have been intended to raise money for anti-war movements, maybe specifically the movement protesting US involvement in the Vietnam War. Her one solo track was Jacques Brel’s “La Colombe,” in a different, longer, French-language recording (albeit with a spoken English introduction) than the English one that was on her In My Life album. Collins also dueted with Joan Baez on Pete Seeger’s “Oh, I Had a Golden Thread” and sang Donovan’s “Legend of a Girl Child Linda” with Baez and Joan’s sister, Mimi Fariña. I think “Legend of a Girl Child Linda” is the only track that’s been reissued (on Baez’s Rare, Live & Classic box, where it’s erroneously annotated as “previously unreleased”).

Most of the other artists on the album are noted women folkies and folk-rockers, including Odetta, Buffy Sainte-Marie (I think her version of “Universal Soldier” here is different from the familiar original one she recorded for Vanguard Records), Malvina Reynolds, Janis Ian (again I think her “Janey’s Blues” here is different from the one on her debut LP), Barbara Dane (doing Dylan’s “Masters of War”), and Hedy West. As the catalog number was W-001, this was likely the Women Strike for Peace label’s first release; I think it was also its only one.

I only saw this album once, in a private collection, and only heard a little of it. I’m pretty sure all the songs the artists had previously recorded are presented here in unique versions done specifically for this LP, though I can’t confirm that without hearing the disc. It seems odd this has never been reissued considering how well known most of the performers are; maybe there is a rights issue involved.

And now for a paragraph of side note trivia: Co-producer/co-coordinator Ethel Raim Dunson, under the name Ethel Raim, co-edited (with Josh Dunson) the 1973 book Anthology of American Folk Music. It transcribed recorded performances from the Folkways 1952 compilation of the same name, which is regarded as perhaps the first important reissue of early folk tracks, helping fuel the folk revival. (The book also includes interviews with Folkways head Moe Asch and early country music A&R man Frank Walker.) I’m guessing Raim was related to Walter Raim, who plays banjo and twelve-string guitar on some tracks on Collins’s outstanding 1963 album #3. Walter Raim, in fact, plays guitar on Collins’s pre-Byrds version of Pete Seeger’s “Turn! Turn! Turn!”; though it had often been assumed the guitar had been played by a pre-Byrds Roger McGuinn, McGuinn later clarified he was ill with the flu when the song was cut, and Raim played on the track.

PH Phactor Jug Band, Merryjuana album. Although it was recorded in Seattle in 1967 (and not released at the time save for two songs that appeared on a rare single), this has something of the sound of San Francisco (where the group had been based for part of 1966) in its heavy strains of the jug-band-cum-psychedelia of the Charlatans. It was wildly uneven and sometimes pedestrian, but it also has some fine off-kilter early psychedelia that could blend forceful blues-rock with glistening ethereal sections, gnarly electric white-boy blues, and raga rock. Little known even when it finally somehow escaped onto vinyl on the small Picadilly label in 1980, it’s the kind of record reissue labels seem afraid to investigate, whether because it’s a lack of interest in the music or fear of the legal hurdles involved.

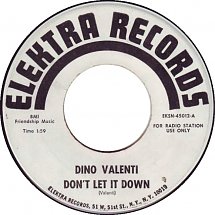

Dino Valenti, “Don’t Let It Down.” Known mostly as the composer of the hippie anthem “Get Together” and as frequent lead singer/songwriter for the early-’70s Quicksilver Messenger Service, Valenti was one of the first folkies to try going electric, if rather gingerly. “Don’t Let It Down,” a rare 1964 Elektra single (probably from pretty late that year), isn’t so much folk-rock as somewhat awkward bluesy rock with harpsichord (by Leon Russell) and pop-soul backup vocals. It’s not that great, but historically interesting. Also not that great, and yet more historically interesting, is the B-side ballad “Birdses,” as it helped inspire the name taken by a group that fused folk and rock far more memorably, the Byrds.

“Birdses” finally did find official release in 2006 on the five-CD box Forever Changing: The Golden Age of Elektra Records 1963-1973. The failure of “Don’t Let It Down” to get reissued is vexing, especially as two Valenti outtakes from the period showed up way back in 1970 on the Early L.A. compilation.

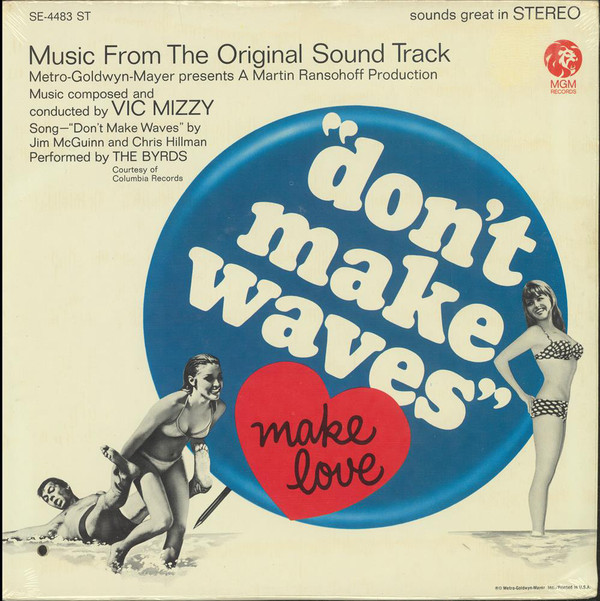

The Byrds, “Don’t Make Waves” (soundtrack version). As the non-LP B-side to the not-quite-hit-single “Have You Seen Her Face,” “Don’t Make Waves” was one of the least essential songs the Byrds released during their classic 1965-67 David Crosby era. It’s a real basic Roger McGuinn-Chris Hillman composition, serving as the theme song for an obscure 1967 film of the same name, though it has characteristically nice Byrds harmonies. And it has, some of you Byrdsmaniacs are already declaring, been reissued as a bonus track on the expanded CD of their Younger Than Yesterday album.

Yes, but actually the version on the Don’t Make Waves soundtrack LP is different. And kind of weird, too — the vocals have a hollow reverb, almost as though they’re singing to the backing track in an empty hallway. Michael Clarke’s had his share of criticism as a drummer, and though it’s usually unfounded and his work is usually serviceable enough, here it’s kind of overdone bashing. It sounds like a demo that got used by accident, or was maybe rushed over to the film’s producers when they needed something before it could get relatively polished in the studio, the vocals seeming to lose some heart near the finish. McGuinn goes into a neat twelve-string figure at the very end, but even that gets botched by the production, which fades it out as soon as it starts.

If this is such a mediocre recording, some might hold the attitude that it’s better off left unreissued. But the Byrds were one of the greatest bands of the time, and it would be good to have everything they did available, including their relatively few misfires. Maybe it couldn’t be licensed for their standard catalog since it appeared on a soundtrack LP for MGM Records, and not on their usual label, Columbia.

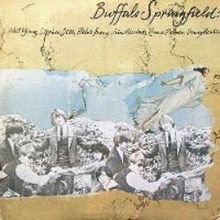

Buffalo Springfield, “Bluebird” (long version). On Los Angeles-area FM radio station KPPC, DJ B. Mitchell Reed made a nine-minute version of Buffalo Springfield’s classic “Bluebird” an underground airplay hit of sorts. As early as 1970, it was reported that Atlantic Records was preparing an album of unissued Buffalo Springfield that would include this extended version. And it did appear on the 1973 double LP compilation Buffalo Springfield. But it hasn’t been issued anywhere else, even on the 2001 Buffalo Springfield Box Set, which had about three dozen outtakes. Maybe the band don’t want it made available, though the 1973 double LP is findable with some effort (and has some very good liner notes in its gatefold).

The nine-minute version is twice as long as the common one that was on their second album, Buffalo Springfield Again, in 1967. Is it twice as good? No. Most of the extra length is taken up by a rather ordinary instrumental jam, and it’s missing the neat coda where the drums drop out, the tempo slows, and a banjo comes to the fore. (A slightly longer one, adding half a minute and taken from acetate, has circulated unofficially.)

Update: just hours after this post went up, Stephen Abbate noted that the long version of “Bluebird” also appears, of all places, on the 1974 Warner Special Products various=artists double LP Heavy Metal: 24 Electrifying Performances. There it keeps company with such early headbangers as Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man,” the MC5’s “Kick Out the Jams,” and Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water,” along with decidedly non-metallic cuts like Van Morrison’s “Domino” and Dr. John’s “Right Place, Wrong Time.” Who knew?

And now, a few honorable mentions to tracks that have been reissued, but on releases that even big fans of the artists might have missed:

Pink Floyd, “Interstellar Overdrive” (1966 version for San Francisco film soundtrack). Probably recorded around late 1966, this hyper-jittery fifteen-minute version of the classic early Pink Floyd instrumental (with extended dramatic drawn-out ending) isn’t just exciting on its own terms. It’s also historically important as one of the very first acceptable-fidelity recordings of the band. It was used as the soundtrack to Anthony Stern’s experimental 1968 film short San Francisco, which is worth seeing for its lightning jump cuts and psychedelic jumble of barely-recognizable San Francisco images, though even some Floyd fans might find it too avant-garde for comfort.

I was surprised that Pink Floyd’s huge 2016 box The Early Years 1965-1972—which included a trunkful of rarities ranging from non-LP singles to soundtracks, outtakes, live performances, and a wealth of film footage—did not include this early version. I referred to it as a previously unreleased version when I reviewed the box set for Flashback magazine and criticized its omission. But even if you also noticed its absence, you might have missed its official release just a few months later on a one-sided single for Record Store Day. As I did, though I already had the track (and the film) on unofficial releases.

The Record Store Day single won’t be too easy to come by, even if it was pressed in a run of 4000, as Floyd’s fans ensured the limited edition would quickly move copies. It’s still too bad no room was made on the box — or on any official DVD or Blu-ray, to my knowledge — for the San Francisco film.

Technically some hard-liners might say this item doesn’t quality for this list, since a track officially unavailable on disc until 2017 can’t said to have been unreissued. It was, however, heard on the soundtrack of a film that was screened starting in 1968, so I’ll be lenient with boundaries here.

The Rolling Stones, “The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man” (long version). Looking for a rare variant by a major band that’s more significant than adding a tambourine beat? They don’t come much more major than the Rolling Stones, but even major Stones fans might have missed this slightly longer version of the B-side of “Satisfaction.” And it’s well worth hearing as (a la Them’s alternate “Little Girl”) another early example of Decca Records apparently censoring one of its best acts. On the extended tag, this long version has Mick Jagger offering a few more wicked imitations of the song’s subject: “I have two clerks…I break my ass every day…here comes the bus…uh-oh…I thought I had a dime…where’s my dime?…I know I got a dime here somewhere…I’m so sharp, you won’t believe how sharp I really am, don’t laugh at me!”

As bold language goes, “I break my ass every day” is several, if not many, rungs below Van Morrison exclaiming the f-word. Still, that’s probably the reason a shorter, ass-less version was substituted after the longer one appeared, according to Martin Elliott’s The Rolling Stones Complete Recording Sessions 1962-2012, “on very early pressings of the UK and US Out of Our Heads album.” It did appear on the 1989 box The Rolling Stones Singles Collection: The London Years, though that’s a hefty price to pay if you just want those additional fifteen seconds or so.

A much more notorious Stones track also came out on an official reissue box, though so briefly that even many Stones completists didn’t catch it. Given to Decca as an up-yours when they needed to give the label one final track as a requirement to wrapping up their contract, the 1970 outtake “Cocksucker Blues” was obviously unreleasable. That wasn’t just because of the title (later used as the title of Robert Frank’s controversial unofficially released documentary of their 1972 US tour). The song itself, performed solo by Jagger on acoustic guitar, is a harrowing and explicit first-person account of gay male prostitution. Yet it somehow slipped out as a bonus single with Decca’s 1983 German box set The Rest of the Best, though it was discontinued shortly afterward. Even one of the world’s top rock memorabilia/record dealers was unaware of this until I brought it to his attention a couple months ago.

Peter, Paul & Mary,“If You Love Your Country.” No, Peter, Paul & Mary aren’t a hip name to toss around these days, even if they did sell tons more records than your Stooges and Beefhearts. Which might seem to make calling this rarity their best late-’60s recording highly relative. But it is a haunting number, and just about folk-rock, with a ghostly organ. The reason it’s so rare? It was recorded for a single in support of Eugene McCarthy’s 1968 presidential campaign that was commercially unavailable, but distributed free of charge at Democratic campaign centers. Even big PPM fans are mostly unaware of this 45, which to my knowledge has been reissued just once — on the massive (13-CD) German box set Next Stop Is Vietnam: The War on Record: 1961-2008. Which means it’s hardly any more known to the general public now than it ever was.

Have some of the tracks listed in this post come out on reissues I’ve missed? Are there notable unreissued ones from this era that are also worthy of mention? Feel free to pitch in with the comments section — more information’s always welcome.