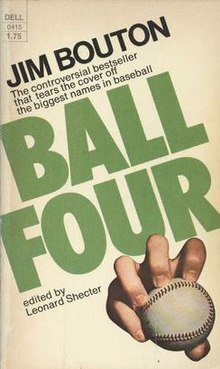

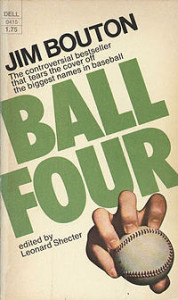

Jim Bouton’s Ball Four is one of the most famous and successful sports books of all time, and deservedly so. There’s not much more that can be said about it that hasn’t already been stated elsewhere. As its Wikipedia entry notes, it’s the only sports book that made the New York Public Library’s 1996 list of Books of the Century, and made Time magazine’s list of the hundred greatest non-fiction books published since 1923 (when Time itself was founded).

But there is a lot more that he wrote, or at least dictated for the transcripts that became the basis for its diary-like text, than has been published. To read it, you have to know where to get it, and make a special effort to access it, especially if you don’t live near Washington, DC.

The Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress has a collection of Jim Bouton papers with more than a hundred containers with about 37,000 items. Probably no one would be able to go through all of those unless they were writing a Bouton biography (and one did come out a few years ago), and maybe not even for that kind of project.

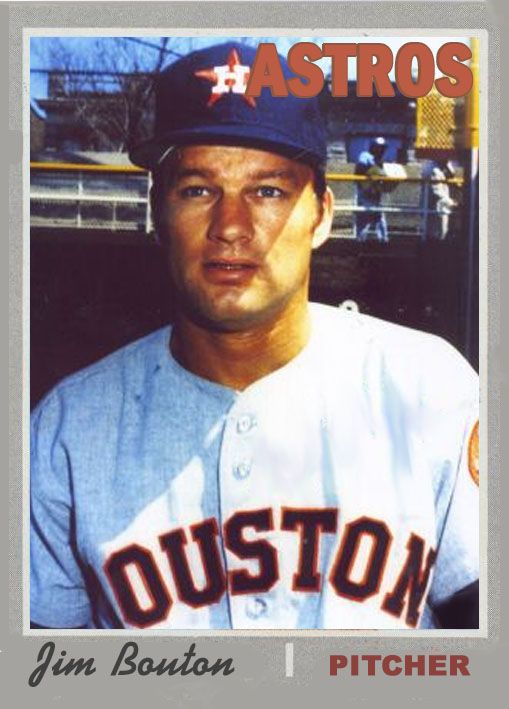

Among them, however, are the original transcripts of the tapes he dictated during the 1969 baseball season that, with editor Leonard Shecter, were turned into the far more concise prose of the Ball Four book. There are also early drafts of the book, though these are much closer to Ball Four in its published form. All of the transcripts, and much of the early drafts, are in just four of the many boxes comprising the Bouton papers.

I went through all of the transcripts, and one of the early drafts, during two days I devoted to looking at the material recently at the Library of Congress. Anyone could do this, as long as you register for a Library of Congress library card (quick and easy to do there in person) and make an appointment with the Manuscript Division a good deal ahead of time (two weeks at least, I’d say), as the material’s stored off-site. But you do have to do it in person in Washington, DC, which I managed to plan as part of a multi-week East Coast trip that was primarily devoted to a work project.

There is a lot more material in the transcripts than the book, hence a lot of material that didn’t make the book. Is it revelatory, or at least worth reading for serious Ball Four fans, of which there are many?

It’s a question that will take a long time to answer, which I’ll try to in some ways with this blogpost. As interesting as I generally found it, it’s sort of like deluxe box set editions of classic rock albums, which I’ve reviewed and dissected much more often than I have literary works. On most deluxe editions, the extra material — the outtakes, the demos, the live recordings from the same era, the alternate mixes, the home tapes, etc. — aren’t nearly as good as the final record, whether they’re alternate versions or songs that didn’t make the album in any form. They’re often interesting, but not on par with the familiar work, and more of value for insight into the creative process than for listening pleasure. Sometimes they are very good from a pure listening standpoint. More often, they’re just okay, or not very different from the final versions.

That’s kind of the case with the Ball Four transcripts. Bouton and Shecter definitely picked the best of the pitcher’s stories and observations for the published book, though there might be a handful of unused ones that should have been considered. In addition, the stories and observations used in Ball Four — even the very best ones — were virtually always considerably pruned from the much longer, more repetitious, and wordier ways they were first voiced in Bouton’s tapes.

That’s to be expected. Bouton was speaking off the top of his head (though he also took some written notes), not writing even rough versions on a typewriter at the end of each day (this being, of course, long before there were word processors that would have those tasks much easier). Often it’s a little like hearing a long version of a classic song, with fadeouts and rehearsals and false starts that can be trimmed, before it’s whittled down to its most effective essential shape.

If you are the type of fan and reader who knows most or all of the stories from the book by heart —and I bet I’m far from the only one —there are a fair number of reasonably interesting ones, or “outtakes,” that didn’t make the final cut, though it takes a lot of patient weeding through the transcripts. While there aren’t many general conclusions to be drawn from what was chosen other than the most obvious previously stated one that he and Shecter plucked the best anecdotes and comments, I do have one.

When Ball Four was published, it sparked an enormous amount of controversy for its depiction of behavior that wasn’t publicized by professional athletes. These included labor disputes, unfair personnel decisions by managers/coaches/ownership, fighting (seldom physical) among players, frequent use of profanity (if commonplace even in mainstream media more than half a century later), and some sex (tame if fairly sexist by today’s standards) and drugs (limited to amphetamines). From some of the outrage it generated among journalists, fans, and the baseball establishment at the time, you might have thought Bouton went out of his way to be as offensive and sensationalistic as possible.

Yet if anything, Bouton held back quite a bit of controversial material — both in terms of stories and thoughts about what he was experiencing — that he dictated into his tape recorder, but didn’t use in Ball Four itself. This included some specific conflicts with other players, sometimes cited by name, that he omitted; citations of drug use and sexual behavior in which famous players were named that didn’t make the book, or in which the story made the book and the player wasn’t named; and substantial criticism of racist or insensitive actions by other players and one manager that aren’t found in the final version. Maybe Bouton was reluctant to go too far and jeopardize his position as a still-active player, especially when detailing the Astros, with whom he’d still be playing when the book was published in 1970. Maybe he felt that getting too personal and cutting too deep would cause too much specific animosity in a few particular situations. Maybe it was a combination of those concerns.

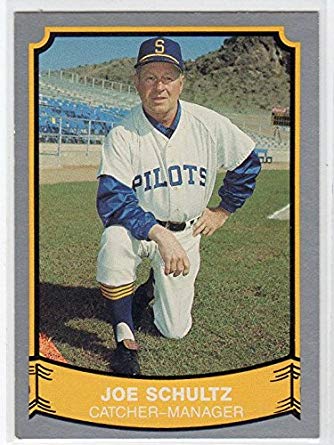

On the flipside, some quite positive comments Bouton made about some associates, particularly Seattle Pilots manager Joe Schultz, aren’t in the final version. Maybe these weren’t felt colorful enough, or were deemed unnecessary considering there are several pretty positive passages about Schultz in the book, something often overlooked by commentators. Some of Ball Four‘s more interesting incidents are fleshed out considerably more fully, sometimes for stories that are fairly brief or presented more lightheartedly in the final version.

There are many examples I could describe in this post, but I’ll limit myself to just a few of the ones I found among the more interesting:

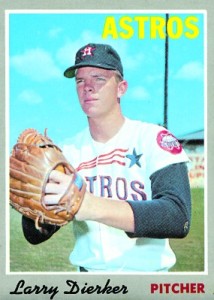

**Although Bouton generally found race relations—not just between blacks and whites, but also between blacks, whites, and Latin players—friendlier on the Astros than on other teams he’d played with, he’s extremely critical of them at a couple points. He notes that two or three players—he doesn’t name them—used the n-word, and not in a kidding manner. He also muses that if changes should be made to the Astros roster, those players should be dispensed with.

He also felt that the team should have traded a few players (rookie pitcher Tom Griffin, who struck out 200 batters in 1969, is mentioned as a possibility) for slugger Richie Allen, then wrapping up a very controversial season in which it was apparent the Phillies were eager to trade him during the off-season. Bouton’s feeling was that Allen was so good it was worth giving him special treatment to have him on a club, at a time when many teams would have shied away from him (though the Phillies did trade him to the Cardinals, in a famous deal in which Curt Flood was included and refused to report to Philadelphia).

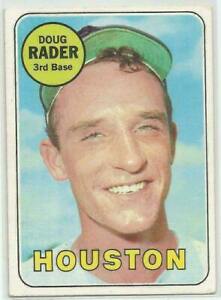

Far from being controversial from our vantage point, Bouton’s attitude toward the prejudiced players seems admirable. Maybe he didn’t, for all the risks he took in Ball Four, want to rock the boat too much with the Astros, for whom he still had to play (if not for much longer) when the book came out. (A brief recommendation that general manager Spec Richardson get fired would have probably caused him far more trouble.) Because Bouton does mention a few white players (particularly Curt Blefary and Doug Rader) who had very good relationships with the blacks on the club, and because he’s generally complimentary about most of his Astros teammates, it’s impossible to say who the offending bigots were, though there might be some suspects more likely than others by process of elimination.

**One of the longest entries in Ball Four is for June 7, when Bouton and some other Seattle players participated in a sports clinic for underprivileged youth in Washington, DC. His friend and roommate Gary Bell was traded minutes after Jim returned to their hotel room, and both events got a lot of space in the book.

On tape, however, an incident at the clinic is treated with much more depth and gravity than it is in the final text. Shortly after arriving at the clinic, Pilots manager Joe Schultz and one of the team’s best players, Don Mincher, simply bailed out as they got impatient and bored with the bureaucracy of getting assigned to run part of the activities. In the book, this is treated as a somewhat quirky and slightly comic turn of events that Bouton views as copping out, without hectoring Schulz and Mincher too much.

In the transcript, it’s obvious this troubled Bouton much more deeply than he let on in the final product. Such was his anger that he talked about it for about half a dozen pages. In part this was because by abandoning the clinic, the pair had failed to come through on commitments that people were counting on, including Hall of Fame player Monte Irvin, then public relations specialist for the baseball commissioner’s office. He states he could never deeply respect either Schultz or Mincher after what happened, though he has a fair amount of positive things to say about both in Ball Four.

**While Bouton held back some of the toughest things he could have revealed, he also held back some comments that would have put his associates in a better light. Maybe this was just done for space reasons, but it’s interesting that in an entry after a good deal of time had passed since Schultz disappointed him in DC, the pitcher’s quite fulsome in his praise of how the manager made sure to put him and Marty Pattin in games after rough outings. He views this as Schultz caring about players and not showing favoritism, looking for the long-range health of the team.

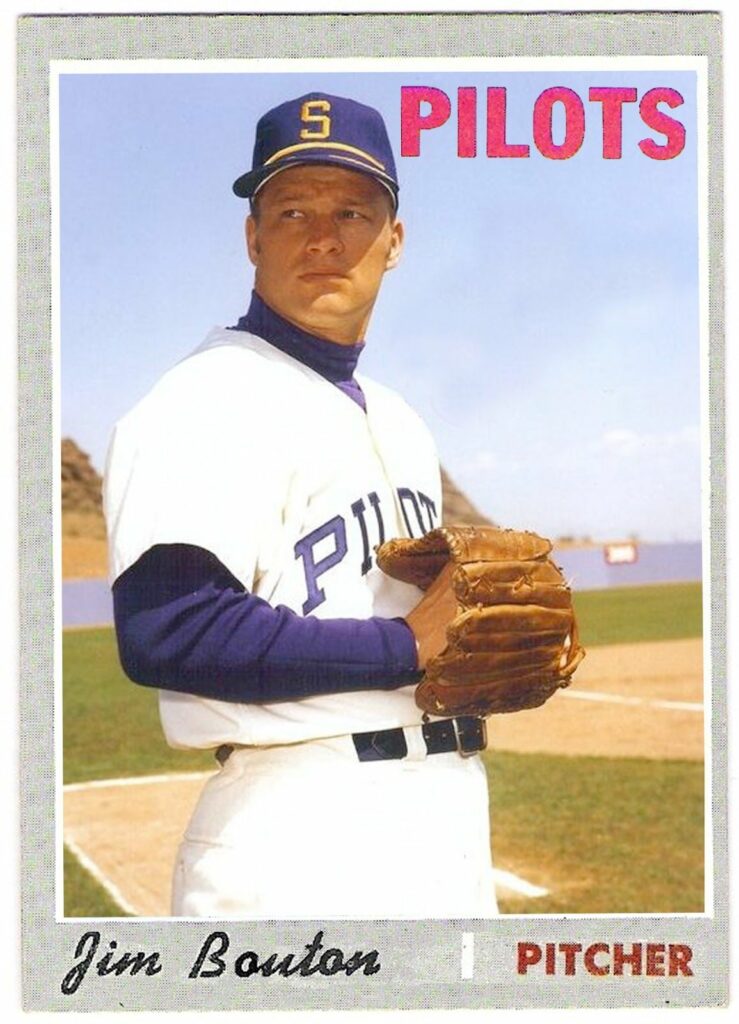

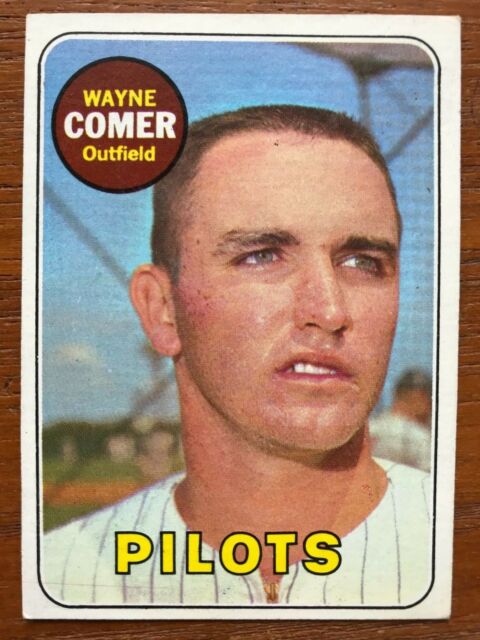

Along the same lines, the Seattle Pilot who comes off worst in the book is outfielder Wayne Comer, mostly as a result of a verbal fight between the pair after Comer profanely insulted a man who’d come by the team bus to thank a teammate for tickets. Bouton makes an important distinction, however, between his view of Comer as a person and his appreciation of him as a player. He’d try to get along with him, he said, and praised his abilities and character in uniform, even if he didn’t care for him as a man.

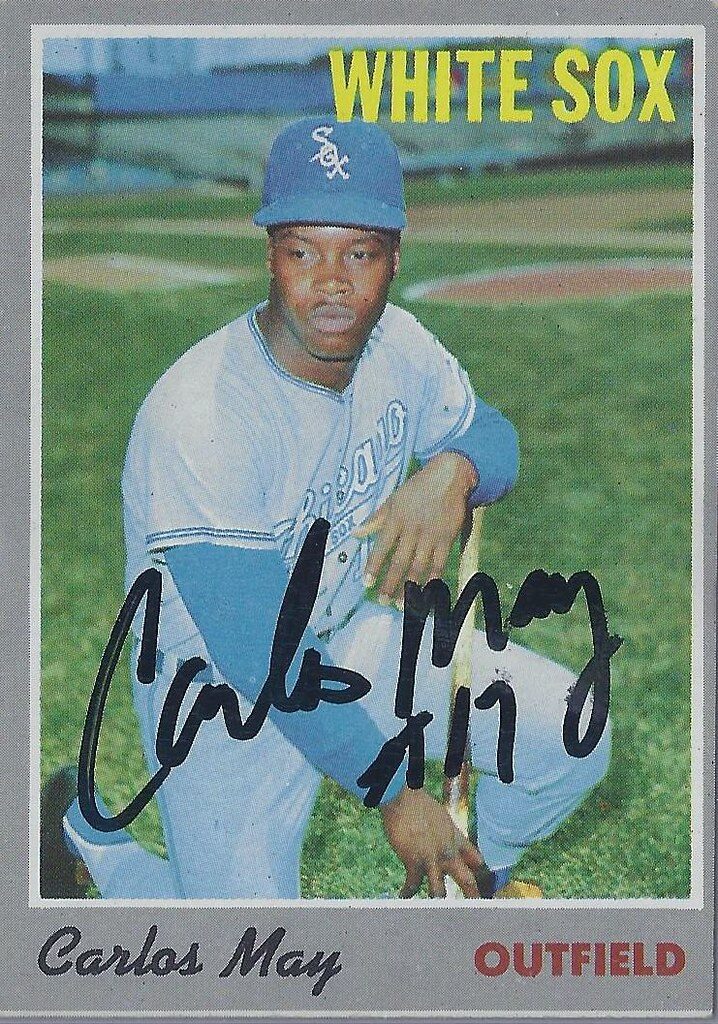

**In summer 1969, rookie White Sox star Carlos May lost part of a thumb in an accident when he was in the Marine Reserves. He had a decent major league career, but the injury probably cost him a chance at a much better one. The incident isn’t mentioned in the book, but on tape, Bouton is pretty critical of what he sees as the military’s stupidity. When he was fulfilling his own military commitment at Fort Dix, he notes, he was never allowed to participate in the dangerous activities like crawling in live machine gun fire. It’s implied that athletes or reservists who might be known to the public were protected in this fashion, May getting injured in a screw-up of that mode of operation.

**Bouton writes about how a Houston sportswriter seemed to think star Astros pitcher Don Wilson’s arm problems were mental, not physical. The book doesn’t detail how he sat down to dinner with Wilson and Wilson’s wife — still sometimes considered daring in 1969, as Wilson was black — and urged Don’s wife not to let him pitch if her husband’s arm was hurting that much. Jim knew it was hurting because Wilson had told him to be prepared to take his place if his arm felt so bad he couldn’t take the mound. Bouton told Wilson’s wife it wasn’t worth risking a career.

**Yogi Berra was fired as Yankees manager after the team lost the 1964 World Series (in which Bouton won two games) to the Cardinals, with Cardinals manager Johnny Keane replacing Berra. According to Bouton’s tape, this decision had been made before the World Series was over — that the Yankees wouldn’t keep Yogi regardless of the outcome. That led to the odd situation of two managers fighting for a championship with one who’d be leading the team he beat the next year, and the other replaced by his opponent even if the Yankees had won. Bouton thought Keane was the only guy involved in the Series on the field who knew about the situation.

**Reserve catcher Freddie Velazquez isn’t mentioned much in Ball Four, other than the disclosure that he earned the nickname “Poor Devil.” The transcripts reveal that Bouton had a friendlier relationship with him, and with some other marginal players like Gus Gil and Billy Williams (not the Cubs star), than you’d guess from their light presence in the final book. It also reveals that when Velazquez caught pneumonia in spring training with the Giants in 1959, he was told by a club official that he’d be released if he didn’t play, though he was under doctor’s orders not to. Velazquez didn’t, really couldn’t, play, and was released the day he got out of the hospital, in Bouton’s account.

**The risk and uneasy logistics of dictating into a tape recorder while he was on the road aren’t discussed much in Ball Four. Bouton was fortunate to have roommates—Gary Bell, Bob Lasko, Mike Marshall, Steve Hovley, and Norm Miller—with whom he got along and trusted to let know he was writing a book. All of them were supportive and kept it a secret, and if any had told on him, it might have cost him not just some status in the clubhouse, but his actual job.

Bouton faced a dilemma of sorts when Bell was traded, unsure of who his next roommate would be. The transcript discloses, though he doesn’t muse upon this in the book, that he’d prefer fellow reliever John Gelnar — a fairly minor Ball Four character —or Marty Pattin, a starter who comes off better in the book than almost any other Pilot (and who would have one of the most successful subsequent careers of anyone on the team). The book could have been different if he’d roomed with either of them, depending on how they reacted to finding out he was writing one. Or it could have jeopardized the book itself, if they were displeased and restricted what he could say in their presence, or even worse let the secret out.

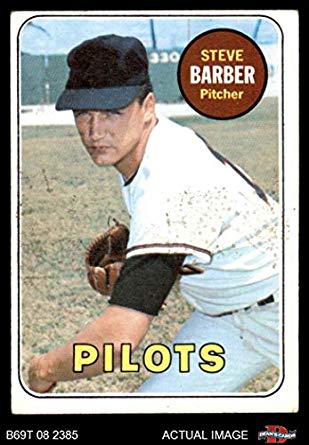

Bouton ended up rooming with Mike Marshall, but only for a few days, as Marshall got sent to the minors. While Bouton didn’t spell it out in the book, he faced an awkward situation when he was then assigned to room with Steve Barber. Barber is one of the Pilots who comes off worst in the book, mostly because of his refusal to go on the disabled list though a sore arm limited his innings, though Jim did appreciate Steve’s willingness to catch the knuckleball in pregame warmups when catchers didn’t want to. It might well have been tense for the two to room together, even if Bouton had somehow hid the project, or Barber hadn’t objected to the book. Over the objections of a Pilots executive, Bouton and three others switched hotel room keys so Jim could room with his friend Steve Hovley, Barber ending up rooming with Greg Goossen.

Bouton’s book-in-progress might not have been as much of a secret as he would have liked. On tape, he admitted near the end of his time with the Pilots that it must have seemed apparent he was working on one, even quoting a suggestion to put something in the book from coach Eddie O’Brien, the figure from the team that comes off in the weakest light. Maybe it was thought Bouton wouldn’t go through with a book, or that there wouldn’t be publisher interest in one from a player who wasn’t a star (even if he’d been a star for a couple years), and indeed was fighting to hang on in the majors.

**One of the more lighthearted vignettes in the book has veteran pitcher Johnny Podres, who’d be starting his final season with the Padres, giving Bouton some pitching tips in a bar in spring training. Like the Pilots, the Padres were also a new expansion team, and it’s observed that Podres didn’t have a contract when he came to spring training to ask for a chance. After a pretty successful career including four World Series wins with the Dodgers, he’d been out of baseball a full year before taking the chance, aged 36. He even got in the Padres rotation and started their second game as a franchise, and though he was 5-3 with a 3.31 ERA on June 1, he was cut by the end of June after a couple rough outings.

**Mike Marshall was sent to the minors by the Pilots in early July, and Marshall’s refusal to report unless they sent him to Toledo rather than Vancouver is written about in Ball Four. What’s not written about is that Bouton went to the trouble of going to Marshall’s apartment the day after Mike was sent down ready to convince him not to quit, telling him what a great town Vancouver (the Pilots’ AAA team) was, how good the Vancouver manager (Bob Lemon) was, and why he should stay in baseball long enough to get a pension.

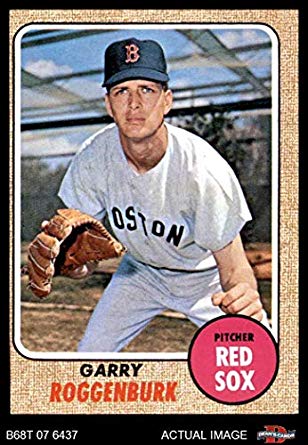

Also discussed in the book is how another Pilots pitcher, Garry Roggenburk, actually quit mid-season although he hadn’t been set down, as he didn’t like the game anymore. Not discussed is that Bouton speculated that if he’d known Roggenburk was that unhappy, he would have tried to talk him out of it before it was too late, making the point that you couldn’t reverse that choice. Although Bouton was criticized in some quarters for the criticisms he made about organized baseball, he clearly thought it was worth the sacrifices and indignities to do what was necessary to stay in the majors, even at a time when it was so much lower-paying and afflicted with unfair labor practices.

**Not everything in the book or transcript is about something mildly or very controversial. It’s sometimes overlooked there’s a lot of good insight into how the game’s played, and numerous stories that don’t have social/organizational dimensions. Like this one that didn’t make the final book, about fellow Pilot pitcher George Brunet. Bouton remembers a time Brunet entered a game to pitch to Mickey Mantle with the bases loaded, looking into the Yankees dugout and knocking his knees together to let them know how scared he was.

I hate to ruin a good story, but I went through Brunet’s relief appearances against the Yankees on Baseballreference.com and didn’t find any such game in which this happened. Maybe Bouton was thinking of August 4, 1963, when Brunet did give up a pinch-hit homer to Mantle, though with the bases empty and not right after he’d entered a close game (which the Yankees won 11-10). Or maybe it was a spring training game.

**One of the more interesting items in Bouton’s Library of Congress file isn’t from the audio transcripts, but a letter from collaborator Leonard Shecter on September 1, 1969. He expresses pleasure about Bouton’s trade to the Astros just a few days earlier, inferring it will be great for the book. He also urges Jim to speculate on why he was traded from the Pilots, with some tough love that’s both the mark of a good editor and might have been tough for Bouton to read.

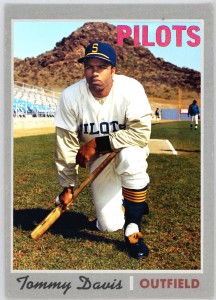

Shecter felt that Bouton had become unpopular with fellow players and the front office, acknowledging the pitcher might disagree. He points out that getting his shoes nailed to the floor—by pitcher Gene Brabender, Jim discovered shortly after the letter—was not an indicator of affection. Shecter wonders if Bouton’s just not the kind of guy to get along with more baseball players than not. Jim didn’t really take Shecter’s advice and speculate much about why he was traded, or consider whether it might have been because he was disliked at the Pilots. He did seem to take Shecter’s suggestion to ask Tommy Davis, a fellow Pilot traded to the Astros just after Bouton was, about this, and that exchange did make it into Ball Four.

There are many other interesting extras in the Ball Four transcripts. Interesting I think, at any rate, to longtime readers who want some more behind-the-scenes details into the making of this classic. There are enough that I might add some others in future blogposts, though this gives you a taste of what awaits at the Library of Congress. And, maybe, one day in a superdeluxe edition of Ball Four that adds some of the unpublished material, complete with contextual footnotes.