Maybe some people who’ve read my work are interested in some of the more everyday basic details of how I work. Maybe not, but at least one person was. That’s Todd L. Burns, who runs the Music Journalism Insider, a newsletter about music journalism. This interview recently appeared on the site, and with his permission, I’m reprinting it here.

How did you get to where you are today, professionally?

I started listening to rock music at the age of five in 1967, after I and the brother I shared a room with got a radio as a holiday gift. I’ve been a big fan of rock since then, starting like so many people did with the Beatles. From there I got into other groups like the Rolling Stones and the Beach Boys, and by the time I was in high school, into great but somewhat lesser exposed vintage acts like the Kinks and the Yardbirds. In college I got into more cult acts like the Velvet Underground, and like so many future rock journalists, got a lot of experience listening to and playing records at my college radio station, WXPN in Philadelphia, which had a huge vinyl library.

The more I heard from rock history (and affiliated genres like soul, blues, reggae, and folk), the more I wanted to hear, and wanted to know. I began writing reviews right after college for a magazine specializing in independent/underground music, Op, and from 1985-1991 was managing editor of a similar magazine, OPtion. After working on some All Music Guides in the mid-1990s, the publisher, Miller Freeman, asked if I had ideas for books of my own. That led to my first book, 1998’s Unknown Legends of Rock’n’Roll, which covered sixty cult acts from the 1950s through the 1980s.

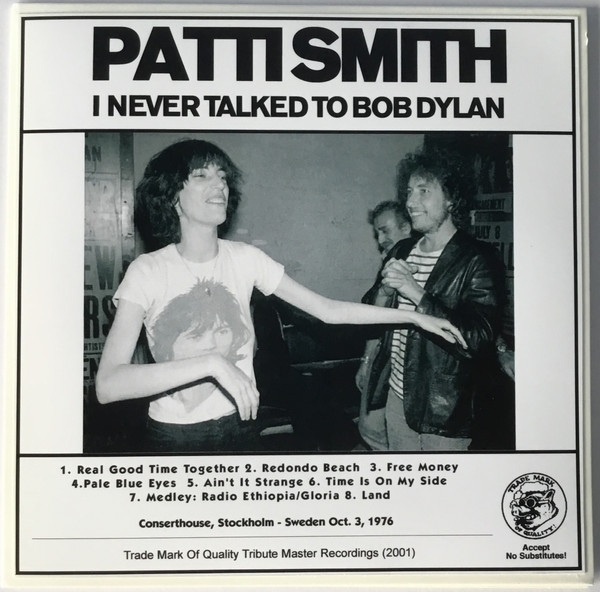

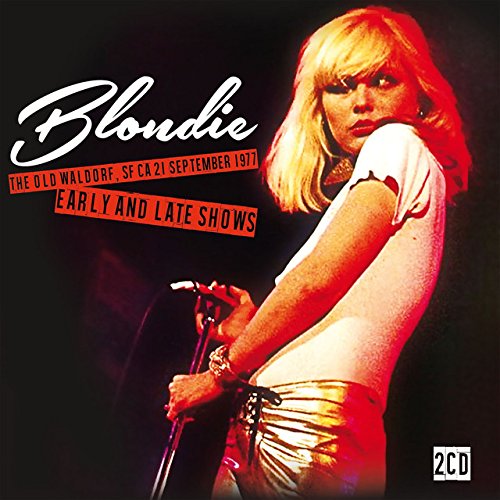

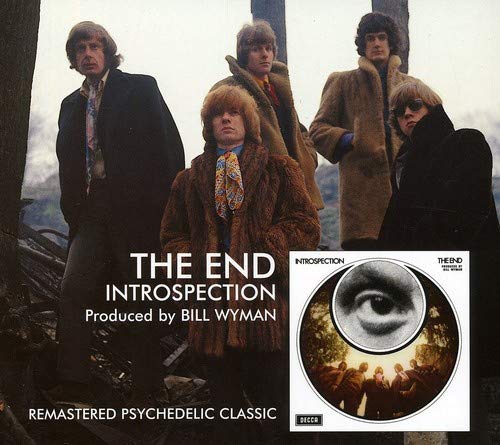

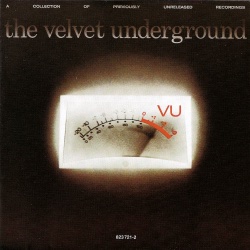

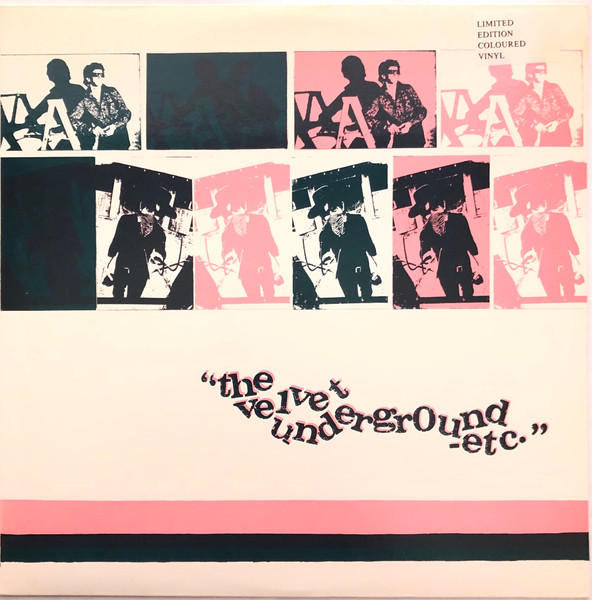

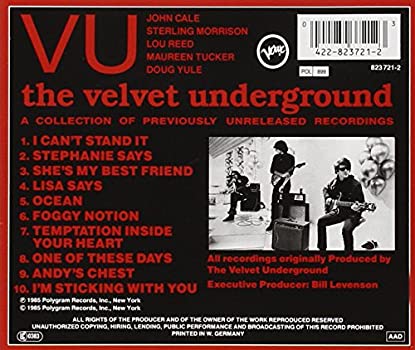

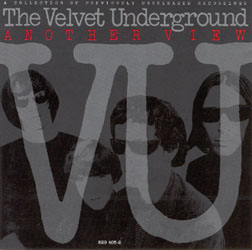

Since then I’ve written about fifteen books, including titles on the Velvet Underground, the Who, and 1960s folk-rock. My biggest focus and enthusiasm is for uncovering little known music history, whether it’s little known material by big acts (as in my book The Unreleased Beatles: Music and Film) or many interesting artists who never got the attention they should have, some of them much more obscure even than cult groups like the Velvet Underground. I’ve never been able to support myself solely through books, which are actually sources of some of the lowest-paying work I’ve done, so I’ve done magazine stories, online stories, liner notes, editing, and other free-lance work all the while. I’ve also presented music history events for about twenty years, and taught full non-credit/adult/community education music history courses in Bay Area colleges for about a dozen years.

But to address the question of how I got to where I am more than what I actually did, some people find the answer boring, but it was perseverance. There’s not a lot of demand for music historians. I pursued every opportunity I could, seldom turning any reasonably interesting work down, and have had to constantly propose book/story/other ideas, many of which have been turned down. I also developed an expertise that not many others have, which has accumulated over a long time, and remains an ongoing process.

Did you have any mentors along the way? What did they teach you?

This might sound pompous, but it’s the truth, although I’m a pretty modest person. I had no specific mentors. I had three older brothers, which gave me more exposure to music history than most people my age, but soon I knew much more about it than any of my siblings. Most of my musical knowledge has come through self-education. There have been people since college that gave me useful professional advice, but usually it’s amounted to “you’re on your own, you have to make your own breaks.”

If there were any figures who taught me things of more specific use, it was from reading the work of people I mostly hadn’t met—the rock writers I liked to read, like Lenny Kaye, Peter Doggett, Johnny Rogan, and numerous others (I did eventually meet all of those guys). I aimed to combine deep research and entertaining prose, as those and many other writers have.

Walk me through a typical day-to-day for you right now.

You might get this answer from a number of people you ask, but there is no typical day. If you’re a self-employed freelancer, as I have been for 26 years, you have to juggle many projects to keep on going. Some days I might have to teach all day. Some days I might have to do and transcribe interviews all day. Some days I might have to write a magazine piece with a deadline. Many days I have to combine all those things. I have to spend more time on rather dull business/financial/organizational stuff—chasing money I’m owed, making sure my taxes are done right, maintaining my computer so I have enough disk space—than most people seem to think.

Generally, a week involves some combination of research, writing, teaching, event presentation (sometimes on Zoom the last few years), and dealing with business stuff as necessary. But there’s not even a typical week, or month. Sometimes I’ve spent weeks at a time traveling to do research. In recent months I’ve had more classes to teach than ever, sometimes every weekday. I can say that generally I get up between 6am-7am (earlier than most writers, it seems) and usually work eight to ten hours from that point. That’s if I’m working at home. Sometimes I need to teach/present in late afternoon or evening, which makes for more like ten-fourteen-hour days. And I have to work on projects from home almost every Saturday and Sunday, often for full weekend days.

What does your media diet look like?

The only rock history magazines I read regularly are a couple to which I contribute: the UK monthly Record Collector, and the ‘60s-oriented rockzine Ugly Things. I usually read parts of the New York Times, Washington Post, and San Francisco Chronicle most days. I don’t watch much TV, and it’s usually public television when I do, though I watch a lot of films of all kinds. Except for baseball and basketball games, I only listen to noncommercial public/college radio, actually more for public affairs than music.

How has your approach to your work changed over the past few years?

The big change was a long time ago, in 1996, when I for the first time became a full-time self-employed free-lancer, working from home except when I was doing research/interviews, or (although not until the 21st century) presenting events and teaching. It’s really always been a jumble of managing multiple projects all along.

How do you organize your work?

I don’t have any special methods, other than labeling my writing and contacts lists on my computer files clearly and backing up what I write every day. I know where to find everything I’ve written on my computers, and where to find the records/books/magazines I regularly consult, though that’s gotten more difficult with my limited space as my collections have grown very big over the years.

Where do you see music journalism headed?

I think any predictions I make would be wrong. There have been a lot of doomsday proclamations about the death of music (and indeed all print) journalism over the last few years, but although there are alarming trends, I don’t think it’s quite that bad. This is hardly an original observation, but there will continue to be a shift toward online platforms rather than print journalism, though I don’t think print journalism will entirely die. I think there will generally be more respect given to music history and non-star artists, though not hugely, and not generally by major publishers.

What would you like to see more of in music journalism right now?

This is pretty selfish, but as a reader and author, I want to see more books on lesser known and cult artists. I’m a big fan of many superstars like the Beatles and Rolling Stones, but I only want books on them if they tell me something new, which is getting harder and harder for such exhaustively covered artists. As many books as I’ve done, I’ve had a hard time getting deals for my books unless they’re on big stars. Hearteningly, there are more and more books on cult artists, but the money involved is so small (as it is, frankly, for many books on more renowned artists) that they’re not worthwhile to do unless authors have other streams of income. Or they can commit to doing one or two such books if they’re really obsessed with the subject, but it’s difficult to do on an ongoing basis.

What’s one tip that you’d give a music journalist starting out right now?

I’m sure you hear snarky answers to this along the lines of: “Don’t do it.” But here’s my one tip, and one that I see given surprisingly infrequently. Write about what you like the most. Tips like “don’t call the main editor, call the managing editor,” “go to the office to pitch in person so they know who you are,” or “study the publications/trends to see what they want/need the most” might be useful for some writers. But I don’t think they’ll make for a very satisfying career if that’s the focus, or if the concentration is more on getting work of any kind than the work you want.

Maybe more importantly, if you write about what you like the most, that enthusiasm and passion will carry through to your writing, and make readers and editors want to read your work more. Also, if you have a thirst for knowing more about and writing about what you like the most, you should develop expertise that will hopefully also help you stand out to editors and publishers if you can write well.

What’s your favorite part of all this?

It’s interviewing the artists and their associates, to get stories and perspectives that haven’t yet been given. Not too far behind is doing research, especially if it’s in sources that few or no one have consulted or yet discovered. I like doing the actual writing too, but finding out new stories and information is what excites me the most.

What was the best track / video or film / book you’ve consumed in the past 12 months?

This is going back a little more than twelve months, and not an offbeat choice, but the Get Back documentary on what the Beatles did in January 1969 had amazing footage that actually unearthed a lot of interesting unknown information in an enjoyable way. If you want something more off the beaten track, the 2022 coffee table book The Byrds: 1964-1967, by Roger McGuinn, Chris Hillman & David Crosby, had a lot of good and mostly little known or unknown photos, but more importantly interesting first-hand memories from all three of those Byrds.

If you had to point folks to one piece of yours, what would it be and why?

The book I’m most proud of actually ended up being two books, my 1960s folk-rock history Turn! Turn! Turn!: The Folk-Rock Revolution and its sequel Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock’s Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock (now combined into one ebook with extra material, titled Jingle Jangle Morning). This is because I was able to weave together many stories and careers into one overview of a major musical movement that had never been covered with one book (or two books, as it ended up), integrating some social history.

For checking out just one piece, I wrote many for the music history website pleasekillme.com, and while they’re not adding new work, the past articles are still up. Several dozen come up if you type my name in the search field. If you want a sample, one of my most comprehensive stories, on a Van Morrison 1968 tape made shortly before he recorded Astral Weeks is here.

Anything you want to plug?

My next book, Do What You Fear Most: The History of the Velvet Underground, is tentatively scheduled for publication by Omnibus Press in London in spring 2025. I wrote a book on the Velvet Underground published in 2009, but it’s been out of print for quite a few years, and it was a day-by-day reference book. This book will be a standard narrative history, which allows me to present the information for wide circulation again, in a more conventionally readable format. I can also incorporate a lot of new information that came to light after my previous book was published about fifteen years ago.