This article first appeared a few months ago on the Fonoteca Municipal do Porto website in a Portuguese translation. I’m making it available here in the original English since a few people have asked if they could read it in that format. The Portuguese translation is here. Fonoteca Municpal do Porto is a sound archive and public space for music appreciation centered around a large collection of vinyl records from the city of Porto, Portugal.

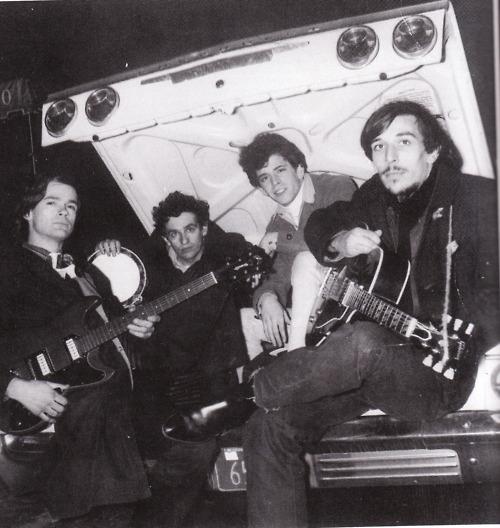

The Velvet Underground released four albums between 1967 and 1970 while Lou Reed was in the band. Each of them is an important statement, and each of them is entirely different from each other. Had the group only issued these four LPs, their place as one of the greatest rock acts would be assured. But the Velvets also recorded a lot of other music in the studio, much of which is nearly as good as what came out while they were active, and some of which is just as good.

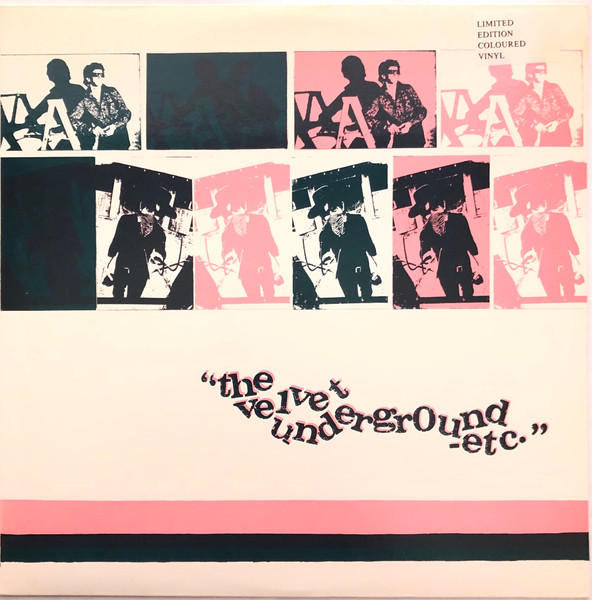

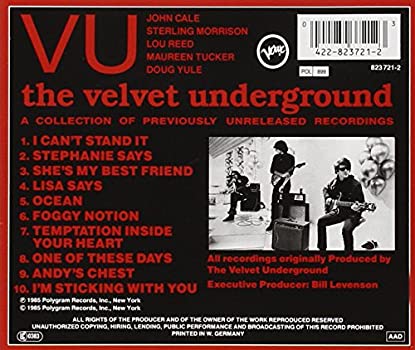

The best of these outtakes, along with some material that clearly wasn’t up to their usual high standards, emerged on the archival compilations VU and Another View in the mid-1980s. VU is an especially vital addition to their discography, featuring much of what would have likely been part of a “missing” fourth album between 1969’s The Velvet Underground and 1970’s Loaded. Another View, sometimes spelled Another VU, is more of a compilation of whatever additional leftovers could be found, although it has some noteworthy highlights.

Much of the material on VU was unofficially circulated on bootleg LPs before its release in February 1985. Back when Velvet Underground bootlegs first started to appear in the 1970s, the possibility of an officially sanctioned collection of the band’s outtakes seemed not only unlikely, but absurd. Their records hadn’t sold well on their official release, and by the early 1970s, some of their early albums were being sold at ridiculously low prices in bargain bins. The MGM label, which had put out the first three LPs, and companies that later acquired the rights to the records clearly thought that interest in the Velvet Underground would disappear.

Instead, the Velvet Underground’s fanatical cult built and built. The mere existence of VU bootlegs, usually reserved for superstars like the Beatles and Led Zeppelin, testified to the intensity of the fans’ devotion. As more and more punk and new wave acts cited the Velvets as a seminal influence, occasionally covering Velvet Underground songs on records and (as Patti Smith did) in concert, the music industry realized there was still money to be made from the VU catalog.

VU was the first of the major excavations into the Velvet Underground’s unreleased material, and perhaps the most commercially successful. It reached #85 in the US charts—a much higher peak position than any of their albums had managed while the Velvets were active, when their highest-charting LP (The Velvet Underground & Nico) only crawled to #171. Of equal importance, it helped turn on a younger generation of listeners to the rich Velvet Underground legacy, ensuring that their four original studio albums never went out of print again.

More important than its commercial impact, however, was the actual music on VU. Eight of the ten songs were taken from 1969 sessions between their third and fourth album. The remaining two comprised a sort of unreleased 1968 single taped between their second and third LPs. Although Another View would be the title of the next outtakes compilation, these ten tracks indeed gave us a kind of “another view” of the Velvet Underground than what we hear on their first three albums.

For the most part, the songs and performances have a more light-hearted, even fun approach than the more serious and abrasive ones heard on 1967’s The Velvet Underground & Nico, still their most famous LP by far; 1968’s White Light/White Heat, easily their noisiest and most aggressive; and 1969’s The Velvet Underground, their quietest and folkiest, yet with lyrics as complex and probing as those heard on their previous work. The Velvet Underground remain most known for their more disturbing and controversial creations, especially those that ventured into previously taboo explorations of hard drug use, unconventional sexual behavior, and dissonant avant-garde drones and electronic distortion. Yet their range also encompassed upbeat, catchy celebrations of pleasure, passion, and rock and roll, as much of the VU compilation demonstrates.

Some of that good-time feel is heard in abundance on one of the two 1968 outtakes, “Temptation Inside Your Heart.” Here the Velvets seem to be trying on soul music for size, though they can’t help letting their inner ambiguity seep through. There aren’t many soul songs, for instance, that would taunt “I know where the evil lies inside of your heart.” Or, for that matter, leave the microphone on so it caught guys murmuring “electricity comes from other planets” or comparing what they’re trying to Motown and Martha & the Vandellas, complete with uncharacteristic upper-register soul harmonies on which they seem on the verge of bursting into laughter.

Also recorded at this February 1968 issue was the lovely ballad “Stephanie Says,” graced with celeste and beautiful John Cale viola, played with as much skill as he brought to the instrument on the more grating drones he employed for the likes of “Venus in Furs.” It seems possible their Verve label (a division of MGM) wanted to somehow coax a commercial single out of the Velvets with these two songs, with the more polished “Stephanie Says” the most likely candidate. Its failure to find release in 1968 is inexplicable, though for all its attractiveness, it coats a typically ambiguous Reed portrait of a globetrotter facing death with bravery.

It also anticipates a few future Lou Reed compositions whose titles follow a woman’s name with “Says,” like “Candy Says” and “Caroline Says.” Also in that sequence is VU’s “Lisa Says,” from the sessions that might have formed the core of a missing 1969 album. This heartbreaking romantic Reed ballad is arguably the highlight of VU, although it’s not as good as the live recording heard on their great concert double LP 1969 Velvet Underground Live (recorded in late 1969, but not released until 1974). That live version has a jaunty second bridge missing from the studio track, and the composition’s failure to get revived for the Loaded sessions is a mystery.

“Ocean” vies with “Lisa Says” as the best song on VU, and is certainly the most serious, Reed and band invoking an almost hypnotic meditative state. The quiet sections contrast with crescendos that ebb and flow like actual ocean waves. This would get attempted again at the Loaded sessions in 1970, though again it’s puzzling that it failed to find a place on that LP.

The other half dozen cuts from the 1969 sessions on VU find the Velvets in a surprisingly cheerful mood, perhaps reflecting a desire to move toward a more rock-oriented and possibly more commercial sound after three years or so of failing to land a hit record. The tunes aren’t in the same league as Reed’s best compositions, but all of them have some charm. “I Can’t Stand It” is an explosive riff-driven rocker, as well as a vehicle for some of Lou’s weirdest humor as he suffers all sorts of indignities while pining for his lost love. “Foggy Notion” isn’t much more than a catchy choppy riff with some engaging absurd lyrics, partially inspired by an obscure mid-1950s B-side by the early rock’n’roll vocal group the Solitaires.

Less impressive, but certainly pleasant, are the uncommonly straightforward midtempo love ode “She’s My Best Friend”; the whimsically wistful “One of These Days,” which shows the Velvets at their bluesiest; and “Andy’s Chest,” an almost comic number with a touch of vaudeville, later explained by Reed as what he thought about Andy Warhol being nearly shot to death in 1968. Drummer Maureen Tucker gets a rare lead vocal on the yet more vaudevillian “I’m Sticking with You,” which almost seems like it could have been used in a western saloon-set musical from the nineteenth century. That puts it in somewhat the same style as the one track on the Velvet Underground’s four principal albums on which she sang lead, “After Hours,” though “After Hours” is better.

Although mildly criticized by some critics and fans for its 1980s-oriented mixes, VU is a valuable supplement to their four fully realized studio albums. It’s more lightweight and not as provoking as any of those records, but consistently entertaining. “Stephanie Says,” “Lisa Says,” and “Ocean” are as artistic as almost anything else the band did at their best. Half of the songs would be remade for Lou Reed solo albums, but in every instance, the Velvet Underground’s version is better and rocks harder.

It’s not exactly the “missing” fourth album between The Velvet Underground and Loaded, however, and not just because two of the songs date from between the second and third LPs. A few more 1969 outtakes were retrieved for 1986’s Another View compilation, which the relative commercial success of VU likely made possible. The album also featured some other outtakes, dating back as far as late 1967. But Another View simply isn’t of nearly as much value as VU, and much more like the sort of random assortment of odds and ends that comprise many archival digs through the vaults.

There are still strong cuts that every Velvet Underground fan will want to hear. The best is the propulsive opening rocker “We’re Gonna Have a Real Good Time Together,” which according to a 1969 article in the Distant Drummer was being considered as a single that year, though it didn’t come out. Basic yet supremely joyous, a live version had long been available on 1969 Velvet Underground Live and outdoes the studio take in sheer frenetic energy. The finest other song on Another View, a 1969 studio version of “Rock and Roll,” is likewise outdone by both the 1969 Velvet Underground Live performance and the 1970 remake on Loaded.

Some of what was unearthed for Another View was unfinished, and it’s often obvious why the other tracks were not released at the time or even chosen for VU. The compelling hard rocker “Guess I’m Falling in Love,” “I’m Gonna Move Right In” (which isn’t much more than a repetitive riff), and the innocuous “Ride into the Sun” don’t even have vocals, although versions exist of all of these with singing.

Filling out the album, two versions of “Hey Mr. Rain” are among the most (and few) monotonous numbers in the Velvets’ catalog. “Coney Island Steeplechase” displays Reed’s sometimes regrettable taste for vaudevillian tunes. To a milder degree, so does the strange “Ferryboat Bill,” its nagging circular melody anchored by a forced pun about a dwarf.

There are many Velvet Underground fans who want to hear everything they can by the band, and they’ll treasure, or at least want to own, Another View. But VU is a much better dig into their archives, and one of the rare compilations of unreleased material that hangs together as a consistent and enjoyable listening experience. The music later appeared on other reissues, including as bonus cuts for deluxe box set reissues of White Light/White Heat and The Velvet Underground. But for the more selective fan, it still serves as the best introduction to the studio material not featured on their 1967-1970 albums, as well as documenting much of the more accessible and rock-and-rolling side of this magnificent band.

Richie Unterberger is the author of White Light/White Heat: The Velvet Underground Day-By-Day.