Rock books are booming, even as the primary sources for first-hand memories pass away or dim in their accuracy and detail. The range continues to be enormous, from the Beatles to David Ackles, from the Rolling Stones to Neil Innes, from Melanie to the Swinging Blue Jeans. I just hope surviving artists and their associates are more conscientious about preserving and making available archival recordings and documents in the time they have left, considering how valuable those will be to future biographers.

There are still plenty of noteworthy books to fill up a list of 25 or so of my favorites. So many have been released, in fact, that some will have to wait until next year’s supplemental list of 2025 volumes, as I haven’t had time to check out everything I might consider, especially if the book came out near the end of the year.

1.Down River: In Search of David Ackles, by Mark Brend (Jawbone Press). Hard-to-classify singer-songwriter David Ackles put out four albums in the late 1960s and early 1970s, none of which sold well, and which have garnered a passionate but fairly small cult following in the ensuing decades. It’s thus welcome to have a full book on this idiosyncratic figure that draws on much research, even if not all the info could be filled in, owing to the death or inaccessibility of Ackles and many of his associates. However, Brend did interview quite a few of them including Ackles himself shortly before the musician’s death in 1999 and, specifically for the book, Elton John’s lyricist Bernie Taupin, who produced Ackles’s third album. He also gained access to some previously unearthed session sheets and unreleased live and studio recordings. This is contextualized by the author’s detailed description of his tracks and compositions, as well as his perspective on how Ackles fit or, maybe more accurately, didn’t fit into the thrust of his era’s popular music.

Ackles almost backed into a recording career by chance, a meeting with an old friend leading to a writing and, soon, recording deal with Elektra Records. Although there were elements of rock in his records (primarily the early ones), he was really more of a theatrical singer-songwriter, with dabs of folk, jazz, music hall, and satire. Writers of the time, even big fans of his, struggled to come up with reference points in their reviews, comparing him to Randy Newman, Judy Collins, Nilsson, and others, though ultimately he wasn’t too similar to anyone. This both made him more interesting than many cult figures, but also less successful in his time and even after his time, as his music was less accessible than many of his peers working in roughly the same areas was, and certainly less related to rock, even if he was primarily marketed to a rock audience. Elton John and Bernie Taupin were big fans, Elton topping a bill over Ackles at his breakthrough 1970 live Los Angeles performances. Taupin producing Ackles’s third album didn’t help David sell many records, however, though he got some extraordinarily effusive reviews.

Brend is an intense fan, but doesn’t get carried away, acknowledging there are reasons Ackles hasn’t had a huge rediscovery and resurgence in recent years along the lines of Nick Drake, or even Judee Sill. Besides describing many of the rare and unreleased recordings in the main text, he also wrote a specific lengthy appendix going into all the unreleased live and studio recordings he was able to research (and often hear) in great detail. (My interview with the author about this book is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/interview-with-richard-morton-jack-editor-compiler-of-world-countdown-august-1966-july-1967/).

2. The Doors: Night Divides the Day, by the Doors (Genesis). This coffee table book is the Doors’ equivalent to The Beatles Anthology and other volumes of bountifully illustrated oral histories of major acts. All of the text is devoted to quotes, from brief to very extensive, from the four Doors and a few of their associates. Of course Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek couldn’t be interviewed specifically for this project, but Robby Krieger and John Densmore were, and Morrison and Manzarek are represented (as John Lennon was in The Beatles Anthology) by many archive quotes. Archive quotes from Krieger and Densmore were plucked from various sources too, and other voices represented include producer Paul Rothchild, engineer Bruce Botnick, Elektra Records boss Jac Holzman, and some photographers, filmmakers, a road manager, and some others who worked with the group. So are some other musicians, including Van Morrison, as the then-unsigned Doors supported Them at the Whisky A Go Go in June 1966. (Van Morrison’s most favorite Doors songs, incidentally, are “Break on Through,” “End of the Night,” and “When the Music’s Over.”)

It’s true that many of these quotes can be found in various books and other sources by and about the band, and the sources are noted in an appendix, though it would have been good to have footnotes delineating the precise origination of specific quotes. It’s also true that some voices are missing, like manager Bill Siddons and Morrison’s primary partner Pamela Courson, though much more information can be found about Morrison’s personal life in various books if you want it. The focus here is mostly on the music, and it does a good job of hitting many of the interesting points about their songs, albums, and career arc from beginning to end, even including a bit about the post-Morrison Doors. And even if you’ve read as many books about the Doors as I have, you’re not going to automatically recognize the quotes and stories you might have previously come across.

There are also many photos from throughout their career, quite a few of them rare, and a good number previously unseen to my knowledge. These are augmented by a fair share of memorabilia like tape boxes, show posters, handwritten lyrics, and tickets. Of particular interest for me, in the section on The Soft Parade, there are some observations from both Krieger and Morrison explaining why songs on that album were credited to individual writers, instead of bearing the group credit found elsewhere. In particular, Krieger says had hadn’t written much before then besides “Light My Fire” and “Love Me Two Times,” Morrison noting that “in the beginning, I wrote most of the songs. On each successive album Robby contributed more songs until finally on this album it’s almost split between us.”

3. The Island Book of Records 1969-70, edited by Neil Storey (Manchester University Press). This is the second volume of this coffee table book series, the first having covered the history of the Island Records label from 1959-68. Why suddenly just two years instead of a decade, for a book that’s about as big, with 432 very large-format pages? These were the years when Island became a much bigger force in the marketplace, and particularly the album-oriented rock one. In just these two years, it issued hit albums (and occasional hit singles) by Jethro Tull, Blind Faith, Traffic, King Crimson, Free, Cat Stevens, Fairport Convention, and Emerson, Lake & Palmer. There were also influential folk-rock albums with a smaller audience, particularly the debut by Nick Drake, but also on LPs by Fotheringay and John and Beverley Martyn.

All of Island’s releases in these two years are covered in this hefty volume, with extensive oral history-formatted text and a heap of graphics. The text has quotes from the period, from archival sources, and from many interviews done for this book with many of the artists; people who worked at Island, most notably the company’s head, Chris Blackwell, whose contributions aren’t token, but quite extensive; and others of note, from journalists and LP designers to producers and record store clerks. The illustrations include plenty of those LP covers, of course, but also many advertisements from the era, along with photos, tape boxes, telegrams, press releases, press clippings, charts, inner label variations, and more.

The previous volume in this series had more typos and miscellaneous inaccuracies than it should have, and while a few creep in here, generally there’s a big improvement in those areas. The quotes are almost all interesting, with in-depth insights into the artists, their records, how they were produced, and how Island marketed and distributed them. “All of Island’s releases” really does mean all of them, including some by acts that didn’t really take off, like If, and the occasional weird rarity, like the avant-garde record by White Noise. And even the occasional unreleased one, like a live Traffic LP that was canceled in late 1970. There’s a section for the label’s singles, some of which had non-LP tracks or alternate mixes/versions.

Some of the text dives really deep, to the pleasure of intense collectors, like a graphic detailing exactly who is who on the cover of their popular 1969 sampler LP You Can All Join In, or the intricate explanation of why a planned album by blues/folk singer Ian A. Anderson came out on a different label. (There are different explanations, but his coincidental bearing the same name as the most prominent member of Jethro Tull seems likely to have had something to do with it.) The most renowned records get the biggest spreads, and these aren’t necessarily the biggest-selling ones of the time, with Nick Drake’s Five Leaves Left getting plenty of ink. So do some acts that might not interest nearly as many readers, like Bronco, though generally the apportionment is as you would expect. It can be a little confusing when non-famous people, like Island staffers, are quoted and it’s hard to follow what exactly their position was, but one of the appendices has bios of everyone quoted.

4. Boom Boom Boom Boom American Rhythm & Blues In England 1962-1966. The Photographs of Brian Smith, by Simon Robinson (Easy on the Eye). Music enthusiast Brian Smith was for the most part an amateur photographer in Manchester in the 1960s, though some have of his photos have previously been published. As it’s one of the biggest cities in England, many touring musicians made Manchester a stop when US blues, soul, and rock’n’roll singers started playing in the country more often by the mid-1960s. In fact, judging from the collection of pictures featured in this 180-page book, very few other towns—including those in the US—would have hosted so many legends in such a short period of time. Listing all of them would take up more than one paragraph, but for a start, there are close-up shots of Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, Little Walter, Big Mama Thornton, Howlin’ Wolf, Carl Perkins, Bill Haley, Sonny Boy Williamson, and many others. And these aren’t mere snapshots taken by an unskilled fan. Smith didn’t pursue a career as a professional photographer, but his pictures (almost all in black and white) are generally on par with the best taken of such musicians during this era, capturing them both onstage and in informal backstage and offstage locales. Although there are some slightly apologetic notes about the condition or imperfections of some pictures, all of them are interesting to see, and many are excellent from both historical and artistic viewpoints.

The photos alone would make this a worthwhile book, but there’s also quite a bit of interesting text that’s not, like many such volumes have, limited to brief captions. There are detailed memories from Smith himself and others about the shows and the performers, and they’re not just bland testimonies to how great the musicians were. There are some pretty deep digs of interest to serious fans, like Sugar Pie DeSantos citing Connie Francis as an artist who had soul, and Stevie Winwood discovering the Malibus’ soul obscurity “Strong Love,” which he’d sing when the Spencer Davis Group covered it for a small British hit, at Manchester’s Twisted Wheel club. Smith also photographed plenty of British acts, and although they take a small percentage of the book’s pages in a final section, many good ones are represented by rare pictures, including the Rolling Stones in their very early years, the Spencer Davis Group, Eric Burdon, a pre-stardom Rod Stewart (from a time when his name was misspelled “Stuart” on the billing), Alex Harvey, and even far less celebrated names like the Honeycombs, the Outlaws, and Jimmy Powell.

5. Buzz Me In: Inside the Record Plant Studios, by Martin Porter & David Goggin (Thames & Hudson). There were three Record Plant studios – the first in New York, then a branch in Los Angeles, and then one in Sausalito, near San Francisco. This book focuses on their operations in the period between when the New York branch started in the late 1960s and 1980, when some work was done on John Lennon’s final recordings. Many top artists worked in one or more of the studios during this time, including Jimi Hendrix (their initial primary client), Stevie Wonder, John Lennon, Sly & the Family Stone, Patti Smith, the Velvet Underground, the Who, Fleetwood Mac, and Bruce Springsteen. The full list is much longer, and should also include work done on the soundtracks to Woodstock and The Concert for Bangladesh.

There’s not room for this nearly 400-page book to discuss everything on the list in detail, but quite a bit is. This includes stories that haven’t made the rounds much or at all, like how considerable overdubbing and fixes were done for the Woodstock and The Concert for Bangladesh albums; the massive overindulgence of the sessions for Keith Moon’s solo albums, which were excessive even by mid-1970s rock decadence standards; the limitations of Phil Spector’s roles in some albums for which he has production credit; and the mountains of material, much of which has to be unreleased if the reported quantity is accurate, cut by Stevie Wonder. Hendrix was considered the most important source of cash flow before construction of his Electric Lady studio was finished (and he died shortly afterward). There were hopes that Sly Stone could fulfill this role in the early 1970s, which couldn’t happen as his musical output diminished and his personal eccentricities mushroomed, as covered in depth here.

The technical side of the studios’ construction and recording, as well as the business machinations between owners Gary Kellgren, Chris Stone, and Roy Cicala, might not be as interesting to the general music fan. But they’re pretty interesting, and also reflect the excesses of the era’s music business with their over-ambitious schemes and heavy drug use and partying. Much of the air went out of those balloons when Kellgren died, along with a girlfriend, in his own swimming pool in a still-mysterious tragedy in the late 1970s.

6. Mann Made: The Story of Manfred Mann 1963-1969, by Guy Mowbray (Red Planet). Structured primarily as an oral history with some linking text by the author, this covers Manfred Mann through the years the majority of Mann fans find their most interesting. While their evolution wasn’t as radical as some of the other top British rock bands of the period, it saw them move from jazz-tinged R&B/rock to out-and-out poppy rock, and through several lineups, fronted by original lead singer Paul Jones and then his replacement, Mike d’Abo. All along, however, they put some quite jazzy and occasionally rather strange and experimental stuff on LPs and B-sides. Even in their earliest and bluesiest phase, they excelled at pop-rock singles, and they were among the first rock acts to intelligently interpret Bob Dylan songs.

Add it up and they were a very interesting and eclectic group, even if they weren’t extremely colorful as individuals (apart perhaps from their lead singers), and hampered by production/management advice not to concentrate on songwriting as much they probably should have. Remarkably, all of the surviving members were interviewed at articulate length — which, also remarkably, includes most of their members, though a few (notably Jack Bruce, their bassist for a fairly brief time in the mid-’60s) were no longer around to participate. Even some guys who were only in the band for a few months or so were tracked down, as well as some early members who didn’t record with them.

It’s odd that although their touring (including in Australia) is covered, their one trip to the US (with the Paul Jones lineup) is barely mentioned, let alone detailed. In the linking text between quotes, the author does sometimes digress at unnecessary length on side topics like the kinds of electric keyboards that came into vogue in rock (not just with the Manfreds) in the ’60s. For the most part, however, the musicians are left to speak for themselves, with insight and humor.

7. Love and Fury: The Extraordinary Life, Death and Legacy of Joe Meek, by Darryl W. Bullock (Omnibus Press). This biography of the legendary, and legendarily eccentric, 1960s British rock producer was preceded by an in-depth biography back in 1989 (and published in 2000 in an updated edition), John Repsch’s The Legendary Joe Meek. Meek’s work and life was fascinating enough that it can merit more than one study, however, and this nearly equally detailed volume is a worthwhile complementary work, even if it inevitably covers much of the same ground. Bullock pays some more attention to Meek’s complex and oft-troubled personal life, though without neglecting his music, thoroughly describing many of the records he produced and sessions for those. While not many surviving Meek associates are left, there are also first-hand memories from many of them, all the way up to one of the future superstars with whom he briefly worked, Steve Howe (when Howe was a teenage guitarist in the Syndicates).

While Meek is most known for the Tornados’ “Telstar,” the Honeycombs’ “Have I the Right,” John Leyton’s “Johnny Remember Me,” and Heinz’s “Just Like Eddie,” many of his other productions are discussed, including plenty that never came close to the hit parade. Some of those were by fairly well known names, like Screaming Lord Sutch and (before his hits) Tom Jones; some featured contributions by future stars like Howe and Ritchie Blackmore; and many are known only to collectors. Actually it’s pretty astounding how many records he produced, and when you consider many tracks were unreleased at the time, it’s an overload that surely contributed to the early death (in a suicide-murder) of a man who wasn’t too temperamentally stable to begin with.

Much of what Meek devised to create his trademark sound – compression, weird effects, sped-up vocals, and influences from the occult – is discussed. But some of the specific best of his non-hits could have been covered in more depth, particularly his attempts to get into more updated “beat group” sounds after Beatlemania had changed the industry. Tracks like the Buzz’s “You’re Holding Me Down” and the Syndicates’ “Crawdaddy Simone” deserve more space than getting simply (if accurately) noted as “freakbeat” classics. So do surprisingly cool efforts from Heinz (with help from ace session musicians like Blackmore) such as “Big Fat Spider,” for all the derision the singer suffered as a no-talent who only had a career due to Meek’s infatuation with him. Much of that slack is taken up by the annotation in the ongoing bulge of reissues of Meek’s work.

8. Dip My Brain in Joy: A Life with Neil Innes: The Official Biography, by Yvonne Innes (Nine Eight). Neil Innes’s widow wrote this book about her late husband, the British singer-songwriter-actor who had one of the greatest gifts for combining music with comedy. It’s not so much a straight biography as a combination of a biography and a memoir of their life together, though it doesn’t suffer for that. Yvonne was with Neil from the early 1960s onward, which means she was there, or there for much of at any rate, his stints with the Bonzo Dog Band, the Rutles, and as a seventh member of sorts of Monty Python, for whom he took on some minor acting roles and often performed music with in their live shows. Also covered are his numerous other activities, which will be lesser known to fans outside of the UK, as many of them were not accessible outside of his homeland. These include his work with future members of Monty Python when the Bonzos were frequent guest stars on the late-‘60s children’s program Do Not Adjust Your Set; Monty Python’s Eric Idle on Idle’s mid-‘70s British TV program Rutland Weekend Times, which inadvertently gave birth to the Rutles; the short-lived supergroup of sorts GRIMMS; and various TV and radio series, as well as many live performances Innes gave as the featured/central artist.

Innes’s wife wasn’t around for all of this, as Neil was often away for extended periods working and touring as their family grew. But she was around for a lot of it, and there are plenty of interesting and amusing inside stories of how his projects worked, dating from the chaotic formation of the Bonzo Dog Band from his art school background. She has a good sense of humor herself, as well as insights into her husband’s take-life-as-it-comes demeanor, which gave them lots of easygoing fun, but also might have made him easier than some to take advantage of in music business dealings. It’s disheartening to hear how he lost copyrights to much of the material he wrote for the Rutles, how he fell out with Idle in a business dispute in the 1990s, and how he didn’t get the money he expected from Spamalot, though this didn’t prevent him from simply getting on with as much fun as he could as he constantly juggled creative projects and touring.

Like so many memoirs, this does lose some momentum after his peak projects are discussed, and by the twenty-first century there are some stories of moderately amusing domestic incidents that aren’t of nearly as much significance as tales of the Bonzos/Rutles/Pythons. But Yvonne Innes is an engaging narrator, and while there might not be as much in the way of hard facts and research as a totally straight biography would boast, her tone is in keeping with the good-natured satirical approach to life Innes projected in his music and other forms of entertainment.

9. Blood Harmony: The Everly Brothers Story, by Barry Mazor (Hachette). With both Everlys gone and many of their close associates similarly unavailable, it’s a challenge to do a biography as comprehensive as it could have been with more first-hand interviews, though the author did some. While there haven’t been many books about the duo, this does the best job of blending coverage of their music, recordings, career trajectory, and personal lives. Although press attention paid to them in their late 1950s and early 1960s peak was superficial, Mazor diligently dug up much such clips, and accessed and depicts many of their filmed performances. As their music got more erratic after 1962, and their story as a whole less interesting after the 1960s, the volume inevitably gets less interesting in its final chapters, though their bitter 1973 breakup and 1980s comeback are detailed, along with how they played out the string as a legacy and retired act in the 21st century. Perhaps their more or less constant feuding and personal differences are played up more than they need to be, but the music is central to the story, including the distinctions between what each brother sang and wrote. To its credit, much more of their catalog is discussed than their big hits, though there could have been more in-depth material on some of their LPs, particularly 1960’s It’s Everly Time and A Date with the Everly Brothers, both of which are among the best pre-Beatles rock albums.

10. Times and Seasons: The Rise and Fall and Rise of the Zombies, by Robin Platts (HoZac). There have actually been previous low-profile books on the Zombies, but this is better and more thorough by far, and not just because it’s a pretty lengthy 350-page biography. There’s much first-hand and vintage interview material from all five of the original Zombies, and the author treats the band as the major British Invasion group they were, not the three-hit wonder they’ve often been dismissed as. While numerous interviews and liner notes have dispensed much of the story, this covers their origins and 1960s work with coverage featuring much detail even some of their bigger fans might have missed. There are plenty of deep quotes from the period from the likes of regional newspapers few have seen, and few have also seen all of the reproductions of vintage advertisements and press clippings used throughout the volume. There’s likewise some trivia even Zombies completists might not have come across, like their serious consideration of covering the Temptations’ “My Girl” when the hits had run alarmingly dry, or keyboardist Rod Argent having written an instrumental (never released by the Zombies) on a mid-‘60s single by the obscure group the Second City Sound.

Note, though, that only about half of this covers the 1964-67 period in which the original Zombies lineup was active. The rest covers the members’ musical activities from their breakup to the present, including the 21st century version of the Zombies with Argent and singer Colin Blunstone. The early part of the post-Zombies section remains interesting, if not as interesting as what the Zombies actually did as a unit, including the stories behind the numerous fake Zombies touring the UK and US to capitalize on the belated rise of “Time of the Season” to near the top of the charts. Rod Argent (and to a lesser extent bassist Chris White’s) early years with the band Argent, and Colin Blunstone’s early recordings as a solo artist, also hold some interest, though less so as the mid-‘70s approach. After that, things become something of a grind through increasingly brief recaps of numerous albums and tours that didn’t make a significant commercial or artistic impact.

There could have been more musical/critical description of their numerous 1960s recordings, particularly their non-LP singles, that were very good and intricate, even if they didn’t sell much. Sometimes more attention is given to how high they charted than how they sounded, though if you’re interested in how they charted in non-US/UK territories, and on infrequently consulted charts like those compiled by pirate radio stations and local US stations, an astonishing number of statistics were dug up for those. For more specific info on the songs and the recordings, you can find it in the extensive liner notes for several fine compilations Alec Palao assembled for Ace Records.

11. Richard Manuel, by Stephen T. Lewis (Schiffer Publishing). This 400-page book is not only a hefty biography of the Band multi-instrumentalist (principally pianist), singer, and occasional songwriter. It’s so thoroughly detailed it also nearly functions as a history of the Band, though the focus is on Manuel, and plenty of other information is in biographies of the group, and in the memoirs of Robbie Robertson and Levon Helm. It not only covers his time in the Band (including their Robertson-less ‘80s reunion years before Manuel hung himself in 1986), but goes way back to his bands in Stratford, Canada, before he joined Ronnie Hawkins’s backup group the Hawks. The Hawks mutated into the Band by 1968, and their very interesting years backing Dylan on tour in 1965-66 and then on the 1967 Basement Tapes recordings are also covered in great depth.

Although he wrote some notable songs on the Band’s debut album and was always vital to their sound as a pianist and lead/backing singer, Manuel had an oft-troubled life, though the author concentrates more on celebrating his artistry. Even before his alcoholism became its worst after the Band’s mid-‘70s breakup, Manuel had piled up numerous car wrecks and generally debauched behavior, balanced a bit by a likable personality that won him friends like Dylan and Eric Clapton. He nonetheless suffered from a lack of confidence that contributed to his near-total withdrawal from songwriting after 1968’s Music from Big Pink, as well as general instability that made his post-Band life (and some of his late-Band life) tumultuous.

The text is a little too bubbly and enthusiastic about his musical virtues, making some similar points quite a bit. However, it’s to be commended for discussing his recordings in extreme detail – not just the albums by the Band, but many live tapes, film clips, and studio outtakes, going back to his pre-Band band the Revols, and including live and Basement Tapes-era recordings with Dylan. That might be too much for some casual fans and readers. But more is much better than less, and more books should take such time to document what’s available, official and otherwise. Many pictures of Manuel and his associates from throughout his life are also featured.

12. Insomnia, by Robbie Robertson (Crown). Although this isn’t nearly as long as Robertson’s memoir Testimony, and doesn’t cover nearly as many years, it’s kind of a sequel. Testimony stopped when the Band came to an end; Insomnia covers the next three years or so, when Robertson didn’t record much music, but was extremely busy as a film producer/actor/composer/soundtrack mixer. Much of this was done in association with Martin Scorsese, of whom he was a housemate in Los Angeles during much of the late 1970s. Both of these figures were going through rough romantic and personal times, and much of their anguish was alleviated by drugs and womanizing. Robertson might not have gone as close to the edge health-wise as Scorsese, but had flings of various length with Genevieve Bujold, Jennifer O’Neill, and Tuesday Weld, among others, before reuniting with his first wife. His wilder and tougher experiences are related in an interesting, zippy storytelling manner that’s neither too frivolous nor too regretful about sowing his wild oats.

Even if you’re not a particular fan of Robertson’s music, there are interesting anecdotes aplenty here, many of his intersections with lots of musical and movie celebrities. There’s Robert De Niro, not unexpectedly, and Bob Dylan, though not a huge amount of text related to the latter. But there are also unexpected interactions with film figures like The Battle of Algiers director Gillo Pontecorvo berating Scorsese’s movies as fascistic, or Robertson and Scorsese cutting out of a London restuarant to avoid a simmering confrontation with a loud and unruly nearby table commandeered by Keith Moon. There are also regretful accounts of his loosening ties with the rest of the Band, and although Levon Helm in particular has given a different perspective, here Robertson views the loss of their musical and personal comaraderie with remorse. There also inside tales of how The Last Waltz documentary was edited and finalized.

One puzzling if minor aspect of this generally good read is that Dylan wanted The Last Waltz not to come out before his own documentary, the ill-received and generally little seen Renaldo and Clara. According to Robertson, an attorney assured him he knew what to do to take care of this, without revealing how to Robbie. But this book doesn’t reveal how this was resolved.

13. Is Everybody Ready for the Next Band? The Rolling Stones 1969 US Tour, by Richard Houghton (Spenwood Books). This isn’t a conventional book about the tour itself, but an oral history collecting memories of people who were at the shows. Most are previously unpublished, although there are a few excerpts from reviews of the time. And almost all of the tales are from audience members, which might make for less inside information than band members and their associates, but allows for perspectives that usually don’t make customary biographies and histories. There’s also one exception to the “US Tour” part of the title, as there are also accounts from those who were there at the Rolling Stones’ July 1969 free concert at Hyde Park—the only show they played outside of the US that year, and their first with Mick Taylor, staged just a couple days after the death of the guy he replaced, Brian Jones.

While there isn’t much here that conflicts with the usual reports of how this legendary tour went down, it’s still interesting to read these anecdotal accounts, which have some personal and informal qualities not often heard in more standard surveys. These testify to the general quality, and occasional sloppiness or substandard sound, of the concerts, including descriptions (usually very complimentary) of opening acts Ike & Tina Turner, Chuck Berry, B.B. King, and (though many didn’t pay him much attention) Terry Reid. Some of the more offbeat sources that stand out are the guy who managed to get into the elevator with the Stones as they were going up to their New York press conference; the official photographer of the West Palm Beach Music & Arts festival that was one of their gigs; and a fan who taped a Boston show that’s now been bootlegged.

More general things that stand out is how overwhelmingly young the audiences were for the Stones at the time, largely ranging from the mid-teens to early twenties. A good number were high on something, as was often par for the course during the era, and some managed to sneak in without paying or weave their way to the very lip of the stage—accomplishments that are much rarer in our current era of much higher security, and much vaster crowds. The Stones also often did two sets, and often took the stage much later than the official opening time, leading to crowds that had to wait outside in the cold for hours for the second show, which often finished long after midnight.

Recollections of their final and most famous/infamous show of the tour at Altamont are in the final section, and generally confirm the reports of chaos and violence at the concert, though many simply couldn’t tell exactly what was going on, even if they were relatively close to the stage. There are also several dozen photos (including some prevoiusly unpublshed snapshots of the Rolling Stones onstage), programs, tour itineraries, advertisements, and other memorabilia related to their 1969 tour.

14. Waiting on the Moon, by Peter Wolf (Little, Brown). Even if you’re not a J. Geils Band fan (or a fan of Wolf’s solo music), this is a pretty entertaining memoir. For Wolf focuses not on his records or performance career, although there’s some of that, but on the many people with whom he’s been associated, sometimes very closely, sometimes in more passing but interesting encounters. Those started long before the J. Geils Band, particularly when he was a struggling student and musician in Boston, where he often befriended (and sometimes backed up in concert) blues legends like John Lee Hooker, James Cotton, and Muddy Waters. He was also a good friend of Van Morrison when Morrison was struggling to gain a foothold as a solo artist during his time in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1968. There’s a whole chapter about that, and while Wolf still regards Morrison with affection, it will not refute Van’s reputation as an enigmatic eccentric. There’s also a lot about his marriage to Faye Dunaway—not all of it pretty—and his experiences with some non-musical figures you might not expect to show up, like Andy Warhol, David Lynch, Tennessee Williams, and Alfred Hitchcock. Everything’s relayed with humble humor and an engaging storytelling tone.

What’s missing? Even in a nearly 350-page book—which isn’t as wieldy as it might seem from that number, as there’s a lot of white space between sections—there’s not a whole lot about the J. Geils Band. Wolf doesn’t even go over how they formed until one of the final chapters, and then only in a cursory fashion. What’s covered focuses more on some admittedly interesting (and sometimes shady) navigations of the music business, particularly with Atlantic Records and controversial manager Dee Anthony, than the music. If you’re looking for how he and the group felt about devising their take on blues-R&B-rock in their early records, or even anything about their hits from “Give It to Me” and “Freeze Frame,” there’s virtually nothing. He does discuss and lament the end of his songwriting partnership with Seth Justman, and getting asked to leave the group just after their huge commercial success in the early 1980s. There’s the feeling enough about his career could be saved for a different memoir, and that he might prefer to tell tales about his interactions with celebrities (with booze aplenty along the way). Reader interest in his own music might have been underestimated, and interest in his not-so-extensive times with the likes of Julia Child (and a chapter about exchanging a gift of expensive wine from Atlantic for numerous cheaper bottles) overestimated.

15. Wings: The Story of a Band on the Run, by Paul McCartney (edited by Ted Widmer). Although there are many quotes by McCartney in this book, it’s an oral history, not an autobiography. There are many quotes from people in McCartney’s orbit from the end of the Beatles through Wings’ official split in 1981, including all of the other Wings; two of McCartney’s daughters; and various producers, session musicians, graphic designers, and other professional and personal associates. Some of this material was taken from interviews done for the documentary Man on the Run (not in wide release until 2026), but some obviously is taken from other sources, particularly when the subject hasn’t been alive for many years (most notably in the numerous quotes from Linda McCartney). It would have been good for the specific sources to be noted, even if that’s the kind of thing that only bothers intense historians.

In a 550-page book, inevitably there are a lot of stories and detail, some of which cover familiar territory on the first decade of McCartney’s post-Beatles life, some which don’t. Among the less familiar tales are Sean Ono Lennon remembering how his father John must have played Paul’s 1970 debut solo LP a lot considering how worn John’s copy is (as was the case for other Beatles solo albums), and Paul noting that a TV program of Johnny Cash was a specific inspiration for forming Wings, as he was impressed by Cash’s interaction with his backup band, the Tennessee Three. Wings’ first British tour, an informal and somewhat slapdash affair where they’d show up at colleges unannounced, is given a lot of coverage. All of Wings’ concerts are listed in an appendix, which also includes a discography and timeline.

Unsurprisingly, McCartney and others’ take on Wings’ music and accomplishments is unremittingly positive, although (Band on the Run aside) their albums—and this book also covers McCartney’s first two albums, before Wings were formed—all got mixed and sometimes negative receptions. Critics’ reviews in particular are criticized or viewed as inaccurate or irrelevant in the long run. While it’s true some of their records have gotten a fair amount of retrospective reassessment over the years (and sometimes hailed as maverick indie-like in their attitude despite getting massive distribution and often high-gloss production), the possibility that at least some of this criticism might have been valid isn’t given much examination. There are also plenty of accounts of how their tours evolved into multimedia spectaculars and Wings’ constant lineup shifts, where internal tensions that helped caused them are discussed but not too thoroughly mined. McCartney’s brief jail term for bringing marijuana into Japan is a significant part of the book’s final pages, though his foolishness is somewhat underplayed, especially as the cancellation of Wings’ Japanese tour was crucial to ending the band.

Although the book could have had some more balance, the biggest issue shoving it down this list is that Wings simply weren’t as interesting, musically or historically, as McCartney’s previous group, the Beatles. Allan Kozinn and Adrian Sinclair’s two music-centered volumes (there are more to come) on the first dozen years of his solo career, The McCartney Legacy, have much more detail on his music and recordings, and quite a bit on his general career. The first of those books, The McCartney Legacy Volume 1: 1969-73, is recommended more highly than this perhaps somewhat sanitized quasi-memoir.

16. The Hollies: Elevated Observations: The Graham Nash Years 1963-1968, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). Checksfield’s Hollies book follows the format of several of his previous ones devoted to the discography of certain acts: track-by-track descriptions, basic release information, and plenty of black-and-white illustrations of vintage record covers, sheet music, and ads. Although it only covers the first half decade or so of the Hollies’ career, in his, my and many others’ estimation, that’s by far the best portion of their work, going up to original Hollie Graham Nash’s departure from the group at the end of 1968.

Like his books on the Searchers, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Dave Clark Five, the Brian Jones-era Rolling Stones, Cliff Richard, and the Tremeloes, this is distinguished from most such discography volumes by both its intense attention to detail and actual critical evaluation of the music, as opposed to mere lists. That level of detail encompasses tracks that even completist Hollies collectors might not be aware of, like unreleased BBC sessions, outtakes, and foreign-language versions. There are also lists of the many cover versions the Hollies generated during the 1960s—some of them really obscure—and an appendix documenting their BBC sessions and TV/film appearances. While Checksfield’s love of the group might lead to assessments of their work that some will feel overenthusiastically generous, this is a valuable book for anyone who cares enough about the Hollies to look into their recordings beyond the obvious best-of compilations, and even beyond their multi-disc anthologies.

17. World Countdown August 1966-July 1967,edited by Richard Morton Jack (Landowne). The last years of the 1960s saw the emergence of many underground, or at least alternative-ish, papers that gave far more coverage to rock music than almost any prior publications of the sort had. Most of them are now forgotten and hard to find; many were very short-lived. Some were so odd in their focus, variable writing style, and rococo graphics that they’re hard to easily describe.

World Countdown, published in California from August 1966 to July 1969, was one such magazine, and one of the hardest to classify. It’s also very hard to find, with few surviving in library or institutional collections, and not many having been preserved by private collectors. Author and rock historian Richard Morton Jack has tracked many of them down, and the new book he’s edited, World Countdown August 1966-July 1967, reprints all of them from that year, along with a lengthy introduction covering the history of the magazine.

Original reporting and criticism of the era’s rock scene was not World Countdown‘s forte, although it did have some. Instead, it offered a jumble of reprints of material (ranging from entire articles to bits and pieces) from other magazines; sketchy scene reports and impressions; verbatim reprints of press releases from record labels or publicists hyping specific artists; tons of ads for records, record stores, fashion accessories, music- and fashion-related businesses, and more; and many pictures of music acts from the time, many of them seldom if ever seen elsewhere.

The range of artists covered was almost absurdly wide, from the deepest underground (including quite a few who rarely or never put out records) to the biggest rock superstars, teen pop hitmakers, and even mainstream pop singers. Quite credible early rock journalists could be read in its pages, yet such offerings were outweighed by hype-heavy copy, a good deal of it unattributed. While many of the ads boasted slick professional design, the cut-and-paste layout of many pages could verge on the amateurish.

The obscure pictures and ads are what’s really of most interest, since you really have to sift through the copy to dig out interesting bits of info that rarely surface elsewhere. Some are here, however, like a report on a Fugs concert that mentions their unissued Atlantic album The Fugs Eat It; fleeting bits about Bob Dylan signing to MGM for $2 million (though he’d never record for them) and Capitol considering releasing the Beatles single “A Day in the Life Of” (sic) after the track was illicitly broadcast in advance of Sgt. Pepper‘s release; and Ralph J. Gleason’s accurately enthusiastic review of Jefferson Airplane’s Surrealistic Pillow. Unexpected names pop up among the contributors, like Richard DiLello (before he moved to London and worked for Apple Records) and, as photographer, Ronnie Haran, who helped find acts for the Whisky A Go Go, most notably the Doors. (My interview with the author about the book is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/interview-with-richard-morton-jack-editor-compiler-of-world-countdown-august-1966-july-1967/).

18. Before Elvis, by Preston Lauterbach (Grand Central). Subtitled “The African American Musicians Who Made the King,” this focuses on several key black influences on Elvis Presley as he began his recording career in the mid-1950s: Arthur Crudup, Big Mama Thornton, Junior Parker, black gospel in his region, and brothers Phineas and Calvin Newborn. The first three names are known even to many casual Presley fans, as Crudup was the writer and original performer of three early Elvis cuts (“That’s All Right Mama,” “My Baby Left Me,” and “So Glad You’re Mine”); Big Mama Thornton did the original version of “Hound Dog”; and Parker, besides also recording for Sun Records, put out the first version of “Mystery Train.” The Newborns aren’t so well known as the others, in part because they were principally jazz musicians, and didn’t write/perform songs Elvis covered.

The book’s greatest strength is its coverage of Crudup, Thornton, and Parker, which gives overviews of their careers and doesn’t just focus on the original versions of songs Elvis did, though there are plenty of details on those. Among the other interesting points discussed are Crudup’s struggle to get royalties for the Elvis recordings of his songs (ultimately successful, but not until after his death); Thornton’s composition of “Ball and Chain,” made famous of course by Janis Joplin with Big Brother and the Holding Company; and Parker’s successful transition from raw early electric blues to smoother soul. The Newborns’ connection to Elvis wasn’t as firm, though Lauterbach discusses reports that their stage shows were influences on Presley’s live performances, and also relays the difficulties Phineas in particular had due to his psychological problems, though the jazz he did wasn’t too similar to Elvis’s rock. While the book’s subtitle makes its focus on Presley’s African-American influences clear, this volume underplays the substantial effects white gospel and country also had on his work.

19. Treasures Untold: A Modern 78 RPM Reader, edited by Josh Rosenthal (Tompkins Square). Record Store Day is mostly known for limited edition releases on vinyl and, to a lesser extent, CDs. This 155-page hardback book, however, was a spring 2025 Record Store Day release limited to a thousand copies, though it does include a CD. The dozen chapters present memories, stories, and perspectives by (and occasionally interviews with) devoted collectors of 78s, some of whom are also musicians, dealers, archivists, reissue compilers/liner note writers, and/or record label owners. The authors aren’t celebrities on the order of, say, R. Crumb, although there’s a detailed story of an in-person encounter with him in one of the chapters. But some will be known to general music historians, like editor Josh Rosenthal, who runs the Tompkins Square label (and did some of the writing and interviewing), longtime collector/reissue writer/assembled Dick Spottswood, and record label executive David Katznelson, who’s also worn several hats. The focus is usually on blues, country, and folk 78s, though a few other genres like jazz, gospel, and early rock’n’roll are also discussed.

You don’t have to be a collector of original 78s to find this interesting. (Indeed, very few music fans, even those very interested in this type of early-to-mid-twentieth century music, will be collectors as intense as those featured here.) Much of the best text centers around the adventures these fellows (they’re all guys) had in finding these records, whether navigating dusty antique shops, cleaning out moldy leftovers from recently deceased collectors, or coming across rarities in the most unexpected thrift stores or private homes. Attention’s also paid to the ins and outs of negotiating (often absurdly high) prices, speculations as to the future of 78 collecting as the well runs ever drier, and the significance of preserving this music for posterity as it becomes ever scarcer.

The point’s often made, perhaps to the extent of over-repetition, that 78s are precious because they’re tactile and voice authentic sentiments of great cultural import, with sound quality that some argue to be better or at least different than is possible in other formats. Some valuable pure music history pops up from time to time, however, as in Spottswood’s story of how royalties were obtained for the Rolling Stones’ cover of Robert Wilkins’s “Prodigal Son” on Beggars Banquet. The Rolling Stones couldn’t deny Wilkins was the originator, it’s noted, since the original (and banned) artwork for the LP had graffiti noting “The Prodigal Son” was by Reverend Wilkins.

Reproductions of rare inner labels from vintage 78s, as well as some photos and other ephemera, are dotted throughout the book. The enclosed ten-song CD has covers of roots music 78s from the 1920s and 1930s recorded especially for this disc—Michael Hurley might be the most well known of the interpreters–with the artists, labels, and catalog numbers of the original source versions noted. (My interview with the author about this book is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/treasures-untold/).

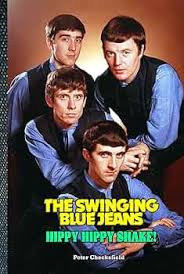

20. The Swinging Blue Jeans: Hippy Hippy Shake!, by Peter Checksfield (peterchecksfield.com). The Swinging Blue Jeans were probably the best and hardest rocking Merseybeat group besides the Beatles and the Searchers, but it still comes as something of a shock to see an entire book about their work. In the US, they’re only known for their sole hit in the country, “Hippy Hippy Shake.” That was a much bigger one in the UK, where it almost made #1, and they also had some other big and small hits in their homeland, especially with their version of the American soul-pop tune “You’re No Good” (the same song Linda Ronstadt had a big hit with in the 1970s). They did, however, record quite a bit—much more than even many British Invasion collectors realize. There’s a four-CD set of their 1963-69 work alone.

Like many of Checksfield’s other numerous books, this is more a reference work than a biography. The bulk of it goes through all of their recordings in order, with some critical description of each one, along with some discographical details. This includes not only all of their singles (of which they had many) and albums (of which they had just a few in the ‘60s, their contents and availability differing according to the country in which they released material), but foreign language recordings, BBC sessions, outtakes, and tracks that only surfaced on obscure compilations. They made many more post-1960s records than people realize—in fact, those take up about half the book—and these aren’t nearly as interesting as the prime earlier work, especially as they were often filled out with remakes of their 1960s songs.

This is a volume for deep British Invasion specialists for sure, but they were a better group than many people realize, and at least get some in-depth appreciation here that will almost certainly never generate another book about them. It’s augmented by numerous black-and-white photos, reproductions of record sleeves/ads/sheet music, and a list of their TV/film appearances.

21. Yoko: A Biography, by David Sheff (Simon & Shuster). For all Yoko Ono’s fame, there hasn’t been much in the way of straightforward accounts of her life. This is the most serviceable one I’ve come across, by the writer who interviewed her and John Lennon for Playboy shortly before Lennon’s death. Much more detail could have been given about her recordings and wealth of artwork in other media, and this is more an overview of the basics of those and her career trajectory than mounds of background information. Sheff, who was a personal friend of Ono’s for quite a few years after the Playboy interviews, is generous in assessing her accomplishments and significance, but does discuss some of the more troubling incidents of her life and controversial aspects of her personality. Those include her trust in psychics; attempts to vilify her while she was married to Lennon, and then to exploit and rob his archives, and extort and threaten her; and the need to provide bodyguards for her and her son for years after her husband’s death.

While Ono’s activities with and without Lennon while they were together have been covered in much depth elsewhere, that’s not as true for her life before and after John. This book fills in much of those eras, including her upbringing in Japan; her extensive avant-garde artistic endeavors in several fields in New York and London before 1968; her resumption of contact with her and Tony Cox’s daughter Kyoko after many years when her whereabouts were unknown; and her fairly prolific, if sometimes intermittent, work in many areas after 1980. Also covered is the shift in the regard in which she’s held by the public, which has given her more respect among listeners, critics, and musicians in recent decades, though there have always been detractors. For some far more intensely detailed description and discussion of her pre-21stcentury work, the large hardback book Yes Yoko Ono is a good one to check out.

22. The Musical Life of Melanie: From the Village to Woodstock and Beyond, by Craig Harris (Rowman & Littlefield). This biography is noted primarily because there’s not much material available covering Melanie’s life and career. As a book, it’s on the matter-of-fact side; sometimes jumps back and forth chronologically; and doesn’t go into extreme depth on some of her recordings and compositions. But there are details about her pre-recording career background, her husband/producer Peter Schekeryk, and some of her compositions, particularly her more famous ones, that aren’t so widely circulated. Her peak years in the late 1960s and early 1970s get the most attention, as they should, and in common with many biographies of popular musicians, the coverage gets skimpier and more rushed the later the decade. Also in common with many such biographies, there are dispiriting behind-the-scenes stories of sexism, poor business ethics within the music industry, and financial mismanagement, in this case on the part of her husband, who sold her publishing to compensate for his unwise decisions. Melanie wrote and recorded more than can be heard on her records, as the 2024 six-CD box Neighborhood Songs revealed, and while that might not have been available to the author before this book was written, it’s unfortunate that material isn’t covered here.

23. Desi Arnaz: The Man Who Invented Television, by Todd S. Purdum (Simon & Schuster). Does this belong in a list of music books? Well, although Arnaz is known more as an actor than a musician, he also made music a big part of his career, and did make quite a few records. Those records are barely mentioned here, as the focus, as per its title, is on his work as a television actor and producer, especially for I Love Lucy. His behind-the-scenes work on that and other shows is pretty interesting as, among other things, I Love Lucy was a pioneering production in being made on film before live audiences rather than broadcast live. Too, his and Lucille Ball’s Desilu production company was among the first to realize the potential of ownership of episodes that could be syndicated for reruns, though gaining those rights were something of a fluke as part of negotiations for other conditions. To this day, he remains one of the most iconic and powerful Latinos to have attained TV stardom. There were downsides to his 1950s superstardom, including relentless womanizing, a stormy marriage to Ball, and alcoholism. This is detailed in this well researched and well told biography, starting from his early days in Cuba and relentless rise through the entertainment ranks after arriving in Florida as an indigent teenager with few resources.

The following books came out in 2024, but I didn’t read them until 2025:

1.Neu Klang: The Definitive History of Krautrock, by Christoph Dallach (Faber & Faber). This is actually an oral history, and as to whether that’s definitive, it covers a lot, but not everything. That’s not to disparage this worthy tome, which has 432 pages of quotes from first-hand interviews with many of the leading figures, and quite a few minor ones, of Krautrock — i.e. German progressive rock of the 1970s. These include members of Can, Kraftwerk, NEU!, Faust, Tangerine Dream, and Amon Düül, all of whom are given chapters of their own. But many lesser known figures are represented, whether from more obscure bands like Agitation Free or people involved in record labels, journalists, managers, record store owners, producers, and fans. There are also interesting chapters on overall topics like Krautrock’s reception inside and outside of Germany, the influence of drugs and communal living, and ambitions or pressures to be commercial (or not).

The memories and stories are generally entertaining enough, both in their content and how they’re told, that this might be a good read even for those whose interest in Krautrock is casual. Particularly interesting are quotes relaying the sociopolitical context for the counterculture that helped give birth to Krautrock. The harassment and repression from authorities that were endured by the musicians were considerable and sometimes astounding, dating back to the sometimes horrid conditions they suffered in postwar Germany with their families and schools. There were also interactions, if usually tangential, with left-wing German terrorists of the 1970s.

There are numerous weird and sometimes humorous stories, and here’s one example. Steve Schroyder of Tangerine Dream was briefly in a Berlin mental hospital after he was “picked up in a department store because I wanted to stroll out with Deep Purple’s In Rock LP without paying, and made no attempt to hide it. I told the staff the record had been made just for me so I didn’t need money to pay for it, and anyway money would soon be obsolete in the modern world, since everybody knew it would soon be abolished. So I was promptly arrested and handed over to the police, where a psychologist diagnosed me with depression…But I climbed out the window with another guy the next day and split.”

2. I Wouldn’t Say It If It Wasn’t True: A Memoir of Life, Music, and the Dream Syndicate, by Steve Wynn (Jawbone). As the most prominent member of the Dream Syndicate, singer-songwriter-guitarist Wynn was a central figure in the Paisley Underground movement in early 1980s Los Angeles alternative rock. Although he’s gone on to a long solo career (and eventual reunions with the Dream Syndicate), this principally covers his early life, especially the formation and career/records of the Dream Syndicate in the 1980s. His very well written, oft-witty memoir isn’t just of interest to Dream Syndicate fans, as it vividly captures the lives of many alternative rock musicians at the time. Wynn followed the path many took to fame (a highly relative term as these bands were far less famous than the ones with huge-selling records) in the scene, from intense fan with college radio shows who worked in record stores (including the famous Los Angeles Rhino Records) to forming a group. There weren’t deliberate plans to become pretty well known within a year, but that’s what happened after they put out a debut EP that got heavy college radio airplay.

Although Wynn thrived on the life of a traveling musician, driving long distances across the country and then Europe for fairly meager pay and variable reception, original bassist Kendra Smith didn’t, leaving the band fairly early on. Wynn hails her as the soul of the Dream Syndicate, and while a few other lineups had some greater mainstream success over the next few years, there’s a sense they never lived up to the promise a lineup including Smith might have had. Moving between indie labels and the major A&M, there are also instructive tales of how their bigger major-label budget and way-extended studio production process shaped their recorded sound into something different, and not better, losing some of what had made them distinctive at their outset. Wynn also relays numerous encounters with many other acts on the same general circuit, some of whom would go on to great success, like R.E.M. and the Bangles, and more of whom would like the Dream Syndicate only achieve different levels of cult recognition. One casualty of their tangled journey from near-amateur punkish group to verging-on-mainstream one was Wynn’s friendship with fellow Dream Syndicate guitarist Karl Precoda, though he’s remained close with others who passed through their lineups.

3. Talkin’ Greenwich Village, by David Browne (Hachette). Subtitled “The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital,” this covers the music that sprang from the Village’s scene from the mid-1950s to the mid-1980s. Even in about 350 pages, you can’t hope to cover everything worthwhile from that vibrant community. But this does encompass a lot, if sometimes in somewhat breezily capsule fashion. It concentrates more on the neighborhood’s folk music than any other style, but the area’s contributions to rock (often from performers originating in the folk arena) and, to a lesser degree, jazz are also included. So are the numerous venues and their frequent struggles to stay alive in the midst of high overhead and significant neighborhood opposition; Washington Square Park, where much of the folk boom got its traction; and the record labels and recordings that emerged, though the emphasis is more on the performances and interaction between key players. Plenty of interesting quotes and memories, some little known, are sprinkled throughout the text, for which Browne did many interviews.

Note that the boundaries of Greenwich Village are tightly defined, so performers more associated with what’s often called the East Village get less attention. The Velvet Underground, Fugs, Holy Modal Rounders, and some other folk, jazz, and rock performers who made much of their reputation a bit outside those boundaries aren’t heavily covered. Some acts who aren’t nearly as well known as the major figures identified with the scene, such as Bob Dylan of course, get more attention than some readers might expect. In particular, Dave Van Ronk, the Blues Project (especially their guitarist, Danny Kalb), and the Roches get quite a bit of ink, including their numerous post-prime attempts to gain some success and recognition. That’s okay, however, as some of the really big names have received a wealth of documentation in other books, and the aforementioned ones are generally underrated and not as well covered as they deserve.

While the Velvet Underground only get a few sentences in the book, one of these has an inaccuracy that needs to be pointed out and corrected. This states that at Café Bizarre, “Their one show was notable for their future mentor Andy Warhol seeing them for the first time and drummer Maureen Tucker not being allowed to play her instrument due to owner Rick Allmen’s objections; they were promptly fired.” The Velvet Underground played more than one show at Café Bizarre, and actually had a brief residency there in December 1965. Although it’s not known exactly how many shows they played there, it was definitely more than one, and almost certainly more like a week or two’s worth. Playing just one show at which Warhol saw them for the first time and they got fired (which they did, after playing “The Black Angel’s Death Song” after being instructed not to by ownership, according to several accounts) didn’t happen.

4. Cher: The Memoir Part One (HarperCollins), by Cher. At about 400 pages, part one of a presumably multi-part Cher memoir covers her life through the end of the 1970s. Those are probably the years readers primarily interested in her music will be most interested in, though those who want to hear about her movie career will have to wait until the next volume. This is very detailed from her earliest years, with a lot of time given to her rough childhood and adolescence, which saw her move countless times and bounce between relative comfort and poverty. Sonny Bono doesn’t enter the story until after around 125 pages, and the narrative picks up in relative excitement around that point, as Cher finds her voice (having never before sung professionally) as a backup singer on Phil Spector sessions, and then through some flop singles with Sonny before the duo hits big with “I Got You Babe.” The music and recordings then take something of a background role as Cher gets into their lavish celebrity lifestyle, fashions, fitful attempts to make movies, and comeback to 1970s TV stardom.

Bono doesn’t come off too well, as he was quite possessive, short-changed her in business affairs, fooled around with other women, and generally tried (with much success, until their mid-‘70s divorce) to control both her professional and personal lives. What are his good points? Actually, Cher gives about equal time to his good ones, and she often forgave his indiscretions and resumed professional and personal contact with her even after their marriage had faded, to the point where readers will get exasperated. Her serious mid-to-late-‘70s affairs with David Geffen and Gene Simmons are covered without undue salaciousness, as is her brief marriage to Gregg Allman, hampered as it was by his substance abuse problems. Much attention’s given to her clothes, hair styles, home decoration, and free-spending ways, which could be so reckless it’s hard for those of us who’ve never had nearly as much money to feel too much sympathy when those ways cause financial trouble.

For those who do care about her up-and-down but generally quite successful recording career, there’s a frustrating absence of depth. Some big hits are barely mentioned, and one of the biggest, “Bang Bang,” isn’t mentioned at all. There’s little sense of how she felt about dividing her recording career between the duo outings that produced her first big hits and her almost immediate separate (and soon much more successful) solo output. As far as anything beyond those big hits—and she did make a lot of records—there’s virtually nothing, other than the failure of some pre-“I Got You Babe” singles to catch on.

Although there aren’t many passages that need to be called out for inaccuracy, here are a couple. The Rolling Stones hung out with her and Sonny on their first US tour in 1964, which is interesting, but the ages of Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and Brian Jones at the time are all given incorrectly. More seriously, it’s stated that “Mick and Keith had been arrested in the UK with drugs on them earlier that year,” but that was three years later, in 1967. Her account of their visit to the UK in mid-1965 gives the impression, as she writes, “that we were American and had to go to Britain to get famous first,” but actually “I Got You Babe” entered the US charts about a month before it entered the UK charts, and when it did enter the UK charts, “I Got You Babe” was #1 in the US. Do these things matter sixty years later? Yes.

Coming in May 2026: My 800-page biography of the Velvet Underground, published by Omnibus Press:

Congrats on the new book. Looking forward to it.

Thank you for the list but the most interesting book is yours for sure ..

That’s a really nice review of our Boom Boom book Ritchie. Very sadly photographer Brian Smith died just before Christmas, so I was not able to share it with him but I know his family will enjoy reading it. He leaves a great legacy.

Great list. Can’t wait for your Velvet Underground!