If you have socially responsible investments, there are too many reasons to cheer the incoming Joe Biden administration to fit into one paragraph. Obviously there will be much more commitment to promoting sustainability and alleviating the destructive effects of climate change. Fighting systemic racial injustice will also be a priority.

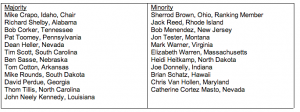

Yet Biden and Congress will also have their hands full fighting the pandemic and boosting the ailing economy—goals that, of course, are deeply interrelated. How easy or difficult will it be to pass legislation that would not just undo the worst policies of the previous administration, but also enact new progressive ones? Much will depend on who’s in Congress, especially a near-deadlocked Senate, which like the House is barely in Democratic control as Biden takes office.

Climate Change and the New Administration

While SRI addresses many issues, most would agree that climate change tops the list. It’s complex and urgent enough that it needs an entire blog post to address, though we hope to examine others in coming months as the new administration settles into place.

Even before taking office, Biden got the discussion into gear by picking a diverse group of environmentally conscious, highly credentialed men and women for key cabinet positions. These include:

- Former Michigan governor Jennifer Granholm, who’s championed renewable energy, as Secretary of Energy.

- Deb Haaland, who would be the first Native American cabinet secretary, as Secretary of the Interior.

- Pete Buttigieg, who attracted plenty of favorable attention as a presidential candidate, as Secretary of the Transportation.

While there are only sixteen cabinet positions, all subject to Senate confirmation, much of the administration’s staff doesn’t have to pass that test. John Kerry’s appointment as special presidential envoy for the climate won’t need to clear that hurdle. Neither will Gina McCarthy, Barack Obama’s EPA administrator, who will head a new White House Office of Domestic Climate Policy.

With near-daily accounts of vicious partisan conflict as policies crawl through the Washington maze, it’s easy to get frustrated, especially with the clock running out on opportunities to stem climate change. Socially responsible investing gives us a chance to make our voices heard outside of the voting booth. It’s not too early to look at how SRI should expand and change our voice for environmental action over the next four years, and hopefully beyond.

Where We Stand Now

With the deluge of headlines over the last four years announcing all sorts of calamitous environmental policies, you might assume it’s been nothing but bad news for building a greener economy. To the surprise of many, that’s not exactly been the case.

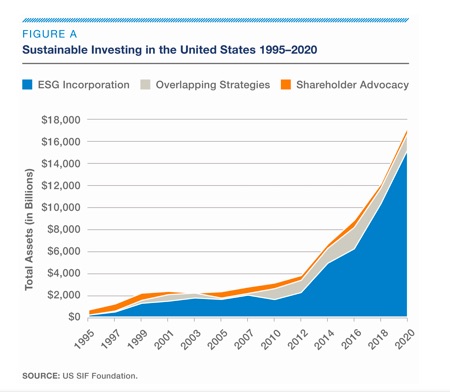

According to the latest report from the United States Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment, total US-domiciled assets under management using ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investment strategies increased to $17 trillion in 2020. That number doesn’t mean much without some context:

- According to Forbes, “The figure represents 33% of all US assets under professional management.”

- It rose 42% over the past two years, from $12 trillion.

- It’s an enormous gain from just a decade ago, when about one in eight such assets were under professional management, as opposed to one in three.

Some cautions are in order when you take in these numbers. ESG is seen by some as shorthand for SRI Light, with guidelines that aren’t as strict as those often adopted by the SRI community. The 33% figure applies to assets under professional management, and is far from representing one in every three dollars in the overall economy. It also counts the ESG assets of huge investment companies like Vanguard, Fidelity, and BlackRock whose overall mission isn’t SRI-centered, and in the view of some not even especially ESG-centered.

Some see this bulge in ESG as a symptom of big players exploiting opportunities for their financial gain, rather than a reflection of their core principles. As renowned environmentalist Bill McKibben wrote in The New York Times shortly after the election, “The fossil fuel industry has been the worst-performing sector of the American economy for many years now. Its problems are twofold: It faces a sprawling resistance movement, rooted in the undeniable fact that its products are wrecking the planet’s climate system. And in wind and sun, it faces formidable technological competitors who can provide the same service, just cleaner and cheaper.”

Along the same lines, some skeptics feel such companies might be creating ESG-sensitive funds to greenwash their public image. Others point out that many financial operations, not just investment companies with ESG assets, are turning toward green technologies out of necessity after demand for fossil fuels tanked when air and car travel plummeted in the pandemic.

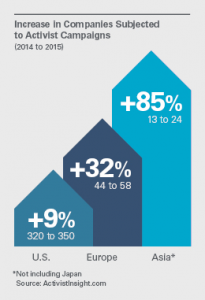

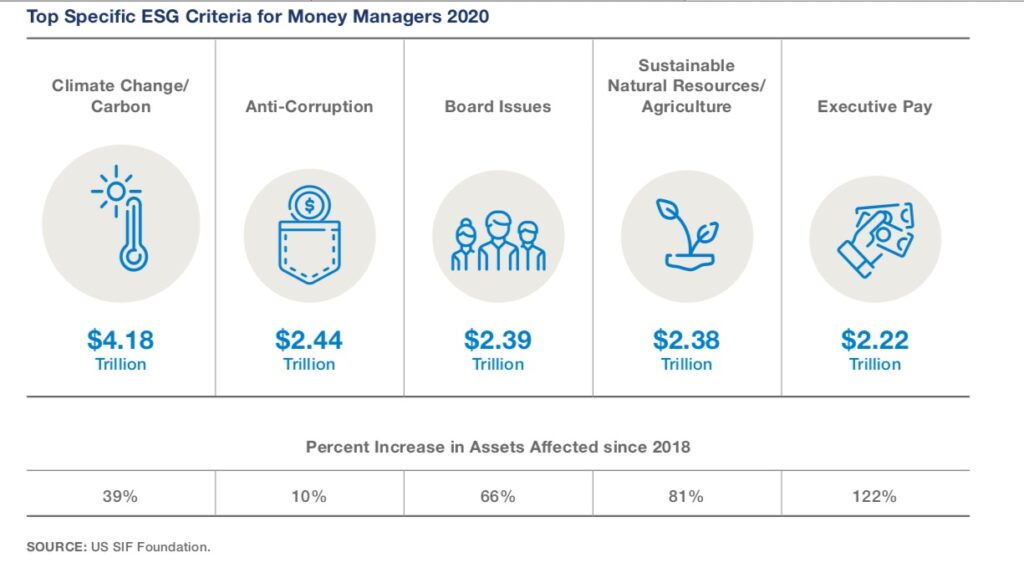

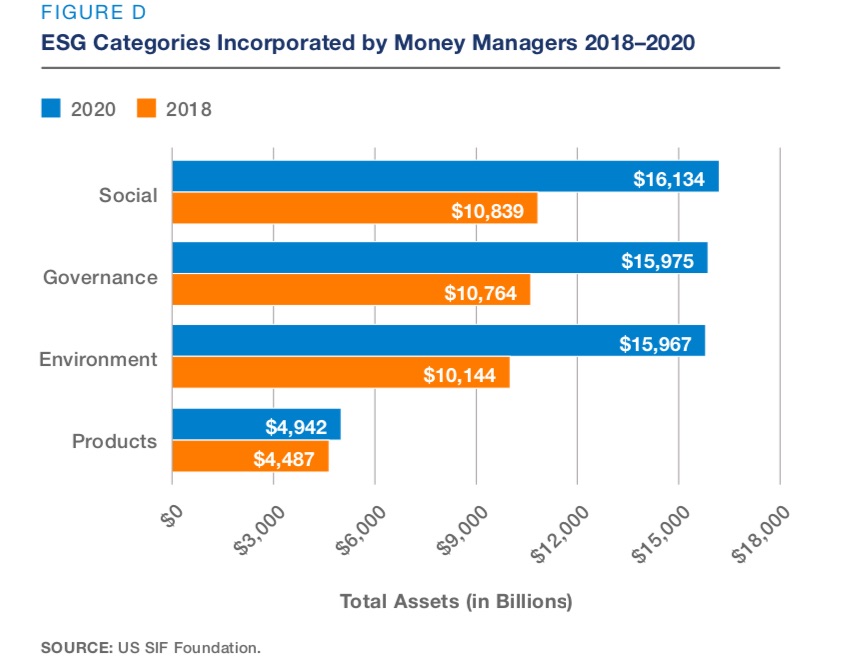

The graphics below give a basic outline of ESG’s growth and priorities:

More Signs to Green Growth

But whatever the motives of companies getting green-friendlier or ESG-oriented, the economy’s generally turning more toward environmentally sustainable technologies and investments. Impax Asset Management president Joseph Keefe put it this way on the site of Pax World Funds, the first socially responsible mutual fund in the US:

“The clean energy sector has managed to thrive despite four years of indifference at best, and opposition at worst, from the Trump administration. Technology cost reductions, supportive state-level policy, and strong demand from corporate consumers responding to customer pressure have all helped renewables grow significantly with extremely limited federal support.” As just one example, although solar tariffs were imposed on imported cells and modules in 2018, the Wood Mackenzie global energy consultancy group expects the solar market to grow by 33% in 2020, and 48% in 2021.

Crucially, this sort of progress isn’t only taking root in mutual funds or private enterprises not known for their altruism. Governments and institutions have also continued to direct their resources toward fossil-free territory.

We only had to wait about a month after Biden was elected to see the sharpest such left turn. In early December, comptroller Thomas DiNapoli announced New York State would start divesting its $226 billion employee pension fund from oil and gas companies if they didn’t have a plan aligned with the Paris climate accord within four years. In 2018, it had been announced that New York City’s pension fund would seek to divest $5 billion in fossil fuel over five years. But New York State’s divestment would be the biggest yet by a US pension.

Such heartening headlines in no way cancel the worst of the outgoing administration’s environmental atrocities. Even as time ran out on its remaining days in office after the election, it was selling oil and gas leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; completing rollbacks on more than a hundred environmental rules; continuing 24/7 construction of a border wall, which threatens nearly a hundred endangered species; and not taking measures to increase controls on industrial soot emissions, although polluted air’s been linked to Covid-19 death rates. Still, the trends toward SRI or ESG investments could help the Biden team get off to a running start not just in reversing these policies, but initiating others. What are the possibilities?

Biden’s Plan

First, let’s take a look at what the new administration plans to address. It will be a brief look because there are literally pages and pages of details at joebiden.com/climate-plan. That itself is a heartening sign, considering the outgoing administration seemed to have no such plan whatsoever, let alone such a comprehensive one. Here are a half dozen highlights:

- Ensure the US achieves a 100% clean energy economy and reaches net-zero emissions no later than 2050.

- Make a federal investment of $1.7 trillion in clean energy and environmental justice over the next ten years.

- Use the federal government procurement system, which spends $500 billion every year, to drive toward 100% clean energy and zero-emissions vehicles.

- Double down on the liquid fuels of the future, which make agriculture a key part of the solution to climate change.

- Make a historic investment in energy and climate research and innovation, as well as clean and resilient infrastructure and communities.

- Re-enter the Paris Agreement on day one of the administration.

There’s much, much more information on this site, titled “The Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice.” These key points alone, however, will both encourage and require massive investment in green technology and environmentally conscious companies. As a New York Times editorial reported, along the way, Biden’s pledged to “eliminate fossil fuel emissions from the power sector by 2035.” That itself would drive a lot of investment away from gas and oil.

The goalposts are sure to shift as socioeconomic conditions change, and as political battles are waged on Capitol Hill. But SRI investment, from both professional management and plain old citizens, will be vital to keeping those goals in sight.

The SRI/ERG Community Wish List

If socially responsible investors have more power than they’ve had in four years—and, perhaps, ever if Biden sticks to his plan—how can their influence be felt in Washington?

“There is a growing chorus of policymakers who recognize that climate change is a material risk to investments,” notes Bryan McGannon, Director of Policy and Programs for the US Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment. “We anticipate that climate risk disclosure by public companies will get attention by the SEC [Securities and Exchange Commission] and Congress in 2021. We also expect the Department of Labor to act on the rules governing retirement plans to clarify how ESG investments may be considered.”

Let’s start with a cabinet position of particular interest to the SRI community. Under new head Marty Walsh, Boston mayor and former union leader, the Department of Labor will probably abandon a proposal requiring plan fiduciaries to prioritize the finances of beneficiaries over social and public policy objectives.

That doesn’t just pave the way for more transparency and ethical behavior from those who administer a great deal of our country’s wealth. It also leaves far greater openings for the initiation of environmentally and socially progressive shareholder resolutions. It would also increase the likelihood of those resolutions having a true positive impact for everyone, and not just benefiting the beneficiaries.

The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment has proposed the creation of a White House Office of Sustainable Finance and Business to promote “the continued growth of sustainable investment and accelerate the shift from a shareholder-centric company model to a multi-stakeholder model.” The second part likewise translates to companies that would be accountable to the health of society as a whole, and not just the portfolios of its investors.

The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment Wish List

This is just the first of eight major recommendations the forum has proposed for the new administration on its website, at ussif.org. If not quite as mammoth as The Biden Plan for a Clean Energy Revolution and Environmental Justice, it’s a lengthy document with dozens of elaborations and sub-recommendations. Here are just some of the other points in its platform likely to be of interest to anyone with a mind toward socially responsible investing, and not just those who make a living at it:

- Appoint leadership at the Department of Labor (DOL) and Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with sustainable investment expertise.

- The SEC should reverse regulatory action limiting shareholder proposals.

- The DOL should reverse regulatory action limiting the inclusion of ESG factors in retirement plans.

- Create a new position of sustainable finance liaison at the Environmental Protection Agency.

- End fossil fuel subsidies.

Some of the forum’s recommendations aren’t specifically linked to SRI/ESG or climate change, such as an urge for a $15/hr. minimum wage and mandatory paid sick leave. Those sort of concerns are nonetheless intimately linked with laying the groundwork for more socially responsible investment, which can best thrive if our overall economy and livelihoods are healthy.

The report’s elaborations on the key eight recommendations include some proposals that aren’t mentioned in Biden’s climate plan, and that might be viewed by many as more progressive. These include suggestions to establish a tax on carbon emissions; restore the Clean Water Act; and, in a measure both wordy and worthy, “establish an Office of Climate and Environmental Justice Accountability within the Council on Environmental Quality.”

Many signs, then, point to a more favorable climate for both fighting climate change and expanding socially responsible investment, an essential pillar in that fight. How might individual investors best allocate their resources in that climate, whether by getting their assets as fossil-free as possible or otherwise? That’s something that can be addressed in a future post on this site.

This story first appeared on the website of Effective Assets.