Last night I gave a presentation at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives about my books on 1960s folk-rock. Most of it was centered around rare film clips, but I was also asked to talk a bit about the research I’ve done at the library over the past two weeks ((thanks to a grant from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation). This is for the expanded ebook edition of my two-volume work on 1960s folk-rock, Turn! Turn! Turn! (published as a print edition in 2002) and Eight Miles High (published as a print edition in 2003), which I’m combining into a single ebook, Jingle Jangle Morning: Folk-Rock in the 1960s.

It would take many hours and many pages to cover all of the material I’ve discovered at the library. So I used just a few images to illustrate how rare items could shed some light on folk-rock’s history, even after having written about it for 600 pages in the print editions. All of these are taken from ads that appeared between 1965 and 1967 in Cash Box, the biggest music trade magazine besides Billboard, but (unlike Billboard) very hard to find copies of these days, in public libraries or anywhere else.

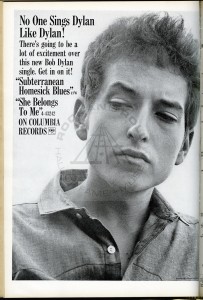

Let’s start with an ad for one of the first folk-rock releases of all, by the most famous songwriter associated with the genre, Bob Dylan:

While Dylan had been a pretty big album-seller for a couple of years by the time this ad (and the 45 it promotes) appeared in March 1965, he had yet to issue a hit single, and in fact had barely issued anything in the seven-inch format in the US. The biggest sales of recordings of Dylan songs belonged not to the songwriter himself, but to Peter, Paul & Mary, who made the Top Ten with “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

This ad shows Columbia got heavily behind Dylan as a singles artist as soon as he made the transition from acoustic folk to rock. Whether that was because they thought rock would be more commercial or because they were getting tired of other labels reaping higher sales from Bob’s songs is impossible to say. But here the company emphatically makes the point that “no one sings Dylan like Dylan” — a phrase that would be quoted many times in subsequent years, and might make its first appearance here. Too bad the ad’s photo (from the cover of Dylan’s third album, The Times They Are A-Changin’) that was about a year out of date by the time “Subterranean Homesick Blues” was issued, both on a single and on Dylan’s fifth album, early 1965’s Bringing It All Back Home.

It wasn’t long before a Dylan song from Bringing It All Back Home got to #1 — not as performed by Dylan, but by the Byrds, who took “Mr. Tambourine Man” to the top of the charts. The Byrds were also on Columbia Records, which might have removed the sting just a little. That ignited a near-instant rush by other artists to cover Dylan songs, even as Columbia issued another Dylan cover from the Byrds’ debut album, “All I Really Want to Do,” as the follow-up to “Mr. Tambourine Man.” In fact, another Hollywood act, Cher, put out her version at the same time, outperforming the Byrds on the Billboard charts. Cash Box took the extraordinary step of combining both versions into the same chart entry, the (presumably) combined sales and airplay getting “All I Really Want to Do” to peak at #9 in the magazine’s listings on August 14, 1965.

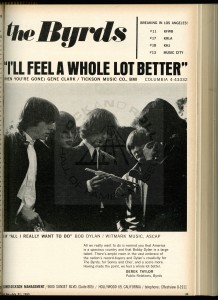

Exercising damage control, and maybe out of desperation, the Byrds’ single was flipped and remarketed with the original B-side, Gene Clark’s composition “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better,” promoted as the A-side. This ad tells the story:

Byrds PR man Derek Taylor (most famed for his work in a similar capacity for the Beatles) tries as best he can to be pissed off with dignity in the ad’s copy, declaring: “All we really want to do is remind you that America is a spacious country and that Bobby Dylan is a large talent. There’s ample room in the vast embrace of the nation’s record-buyers and Dylan’s creativity for the Byrds, for Sonny and Cher, and a score more. Having made the point, we feel a whole lot better.” But despite the ad announcing the single’s entry into the Top Twenty on four Los Angeles charts, “I’ll Feel a Whole Lot Better” wouldn’t break out nationally. At least the incident afforded an opportunity to use a great, seldom-seen picture of the band, with leader Roger McGuinn consulting the slide rule he was reported to carry around with him, this photo supplying the proof.

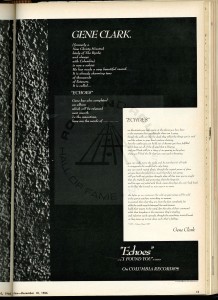

Sliding farther down the Byrds and Gene Clark thread, Clark — the band’s primary songwriter on their first two albums — left the group in early 1966 to pursue a solo career. This wasn’t commercially successful, his debut solo LP, Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers, failing to chart at all when it appeared in early 1967. Clark has a devoted cult following, and many hardcore fans of Clark and other artists who don’t get sales on par with the passion of their admirers blame record labels for the failure of such records to reach a wide audience. Undoubtedly poor promotion is indeed often to blame in such instances, but it’s simply not true that Columbia did nothing to promote Gene’s solo career. The December 10, 1966 issue of Cash Box contained this extraordinary two-page ad for the single that previewed the record, “Echoes”:

It was rare for labels to take out a two-page ad for anything, and also rare, in 1966 at any rate, for ads to reprint lyrics of a single in full. There were a good number of ads that did so in the final years of the ‘60s, however — a change that folk-rock likely did much to foster, as it made rock lyrics (and lyrics in popular music as a whole) taken far more seriously than they had been before folk-rock’s emergence.

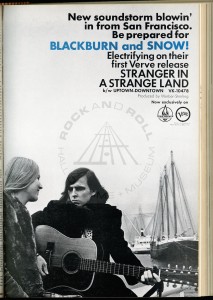

As an aside, there were quite a few instances when I came across prominent ads for records that had been alleged to have been poorly promoted. Take, for example, this single by Blackburn & Snow, one of the finest underrated and overlooked early San Francisco folk-rock acts:

Despite an abundance of fine, and finely harmonized, original material, few tracks (and no LP) were issued by Blackburn & Snow while they were active in 1966 and 1967, though a full CD finally emerged in 1999. Only two singles came out at the time, however, and even those appeared somewhat belatedly after they began their recording career. “I think if it had been marketed well, and it had come out early enough, it would have done something,” Sherry Snow (now known as Halimah Collingwood) told me when I interviewed her for the book. “It isn’t like I didn’t try,” countered Frank Werber (most famous for managing the Kingston Trio), who recorded them for his Trident production company. “There was not a lot of interest. From anybody.”

I don’t want to pick on Halimah Collingwood by using this ad as an example — she gave me a lengthy, friendly, and candid interview. Many other artists have claimed their releases were inadequately publicized. But this full-page ad does indicate that there was some substantial promotion behind their “Stranger in a Strange Land” single, when it finally did come out, about a year the track was recorded.

And as a trivial note, who wrote “Stranger in a Strange Land”? David Crosby, who’d been a housemate of Snow’s in Venice, California, before the Byrds formed. The Byrds tried it in the studio themselves, but only got as far as cutting the song’s unissued instrumental backing track, subsequently released on the expanded Turn! Turn! Turn! CD.

Sometimes ads can tell a more serious story than the loss of record sales due to bungled promotion. Janis Ian’s “Society Child” was turned down by numerous labels owing to its controversial subject (interracial dating), and even after it was released in 1966, many radio stations were reluctant to play it. It was only after she sang it on a Leonard Bernstein-hosted CBS special on pop music in April 1967 that it was picked up by enough stations to make it a national hit. The story’s been told many times, by Ian and others.

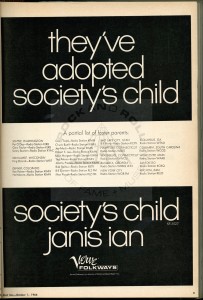

I didn’t doubt Ian’s account, but a couple Cash Box ads supplied vivid proof. Look at this one, from October 1, 1966:

Here the Verve/Folkways label’s praising 17 radio stations in 13 cities that had the courage to play “Society’s Child,” including, most surprisingly, three in the South (in Columbus, Georgia; Augusta, Georgia; and Columbia, South Carolina), where resistance to the single (and integration in general) was heaviest.

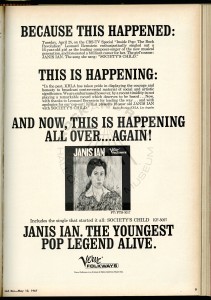

Now look at this ad from more than seven months later, after “Society’s Child” finally started to break out nationally:

That verifies the influence the TV special had in making the single a hit, but more intriguingly, contains this note from KRLA, one of the most powerful radio stations in Los Angeles:

“In the past, KRLA has taken pride in displaying the courage and honesty to broadcast controversial material of social and artistic significance. We are embarrassed however, by a recent timidity in not playing a remarkable record which deserves to be heard…Now, with thanks to Leonard Bernstein for leading the way…and with apologies for our ‘cop-out,’ KRLA presents 16-year-old JANIS IAN with SOCIETY’s CHILD.” — Radio Station KRLA, Los Angeles

A vivid illustration, then, of both the initial obstacles to the record’s success, and network television’s role in getting a key outlet to reconsider its stance. Then, as now, it’s rare for an institution of any sort to apologize for anything so publicly.

By the way, the reason Ian got on the TV show in the first place was because New York Times music critic Robert Shelton played “Society’s Child” for Bernstein’s producer, David Oppenheim, who in turn played it to Bernstein. Shelton’s most known for writing the first prominent, glowing review of a Dylan show (back in September 1961 for the Times), as well as generally helping Dylan’s rise as his most prominent champion in the press. Here’s another instance, however, in which he helped change pop history.

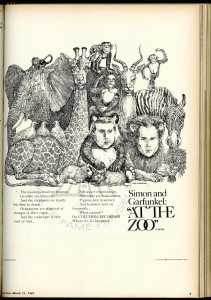

Not every ad has to make such a heavy point to be worth investigating, or tell you much about why a record did or didn’t make it. I leave you with this goofy-as-all-get-out ad for Simon & Garfunkel’s single “At the Zoo”:

Here’s guessing Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel did not see or approve this ad before it got printed in March 1967. Maybe Art wouldn’t have minded being cast as the lion, but it’s hard to see Paul being pleased to be the panda. As the ‘60s finished, artists like Joni Mitchell and Neil Young would insist such frivolous promotion be discontinued. And they’d get their way — just one overlooked example of how folk-rock helped give musicians more control over not just their product, but also their promotion, as musicians demanded and received a voice in how they were advertised.

Thanks to the staff at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives for their help with assembling images for this post.