Hard-to-classify singer-songwriter David Ackles put out four albums in the late 1960s and early 1970s, none of which sold well, and which have garnered a passionate but fairly small cult following in the ensuing decades. It’s thus welcome to have a full book on this idiosyncratic figure that draws on much research, even if not all the info could be filled in, owing to the death or inaccessibility of Ackles and many of his associates.

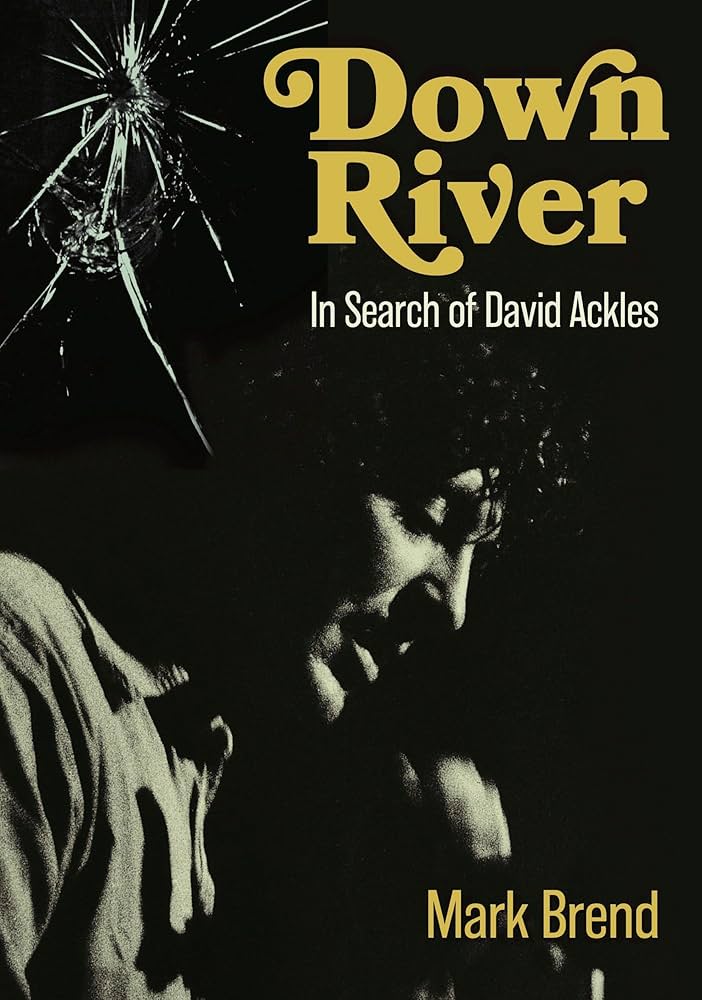

However, for his new biography Down River: In Search of David Ackles (on Jawbone Press), author Mark Brend did interview quite a few of them. Those include Ackles himself shortly before the musician’s death in 1999 and, specifically for the book, Elton John’s lyricist Bernie Taupin, who produced Ackles’s third album. He also gained access to some previously unearthed session sheets and unreleased live and studio recordings. This is contextualized by the author’s detailed description of his tracks and compositions, as well as his perspective on how Ackles fit or, maybe more accurately, didn’t fit into the thrust of his era’s popular music.

Ackles almost backed into a recording career by chance, a meeting with an old friend leading to a writing and, soon, recording deal with Elektra Records. Although there were elements of rock in his records (primarily the early ones), he was really more of a theatrical singer-songwriter, with dabs of folk, jazz, music hall, and satire. Writers of the time, even big fans of his, struggled to come up with reference points in their reviews, comparing him to Randy Newman, Judy Collins, Nilsson, and others, though ultimately he wasn’t too similar to anyone.

This both made him more interesting than many cult figures, but also less successful in his time and even after his time, as his music was less accessible than many of his peers working in roughly the same areas, and certainly less related to rock, even if he was primarily marketed to a rock audience. Elton John and Bernie Taupin were big fans, Elton topping a bill over Ackles at his breathrough 1970 live Los Angeles performances. Taupin producing Ackles’s third album didn’t help David sell many records, however, though he got some extraordinarily effusive reviews.

Brend is an intense fan, but doesn’t get carried away, acknowledging there are reasons Ackles hasn’t had a huge rediscovery and resurgence in recent years along the lines of Nick Drake, or even Judee Sill. Besides describing many of the rare and unreleased recordings in the main text, he also wrote a specific lengthy appendix going into all the unreleased live and studio recordings he was able to research (and often hear) in great detail. I interviewed Brend about the book in September 2025, the month after its publication.

You wrote a chapter on David Ackles in your 2001 book American Troubadours, and managed to interview him for a short piece a few years before that, shortly before his death. Down River, of course, is much more extensive. What most made you want to motivate writing a full-length book on Ackles, who isn’t too well known even by cult figure standards?

MB: The short answer is that he’s one of my favorite recording artists – I first heard his music forty years ago and I’ve never tired of it – and I wanted to investigate his work more thoroughly than I have done before. But in addition to enthusiasm for his music, I became intrigued that his records were and are fervently admired by a small group of people from the music world who, one way of another, know what they’re talking about. I’m thinking of the likes of David Anderle [who co-produced Ackles’s first album and also produced Judy Collins in the late 1960s], Jac Holzman, Elton John, Bernie Taupin, Elvis Costello, Jim O’Rourke, Greg Ginn, Phil Collins, and quite a few seasoned rock writers. I wanted to investigate why Ackles has a small but devoted audience yet failed to make much commercial headway when active and – as you indicate – barely qualifies as a cult figure. Is it something about him and his music? Is it the way the music business is set up? Or are there other reasons?

Although Ackles made four albums and didn’t have the psychological and substance abuse problems or reclusive inaccessibility so often associated with such figures, there really wasn’t too much known about him before you started writing Down River. What did you most want to find out about him and his music that hadn’t previously been uncovered?

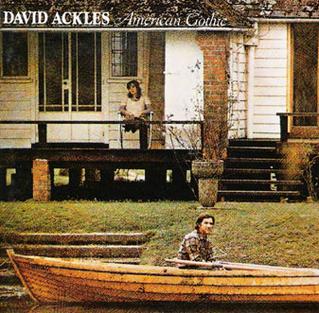

MB: I had some pretty sketchy knowledge of his life before I started serious research, but I wanted to get more detail. For example, I knew about his enthusiasm for musical theatre, but I didn’t know how much work he put into that field of creative endeavor, both before and after his recording career. Similarly, I knew he’d lived in England while recording American Gothic [his third album, from 1972], and I wanted to try and get a sense of what his life was like then. I succeeded in the sense that I now know more about these aspects of his life, and other things, than I did when I started. But of course, there’s so much I don’t know and probably never will.

What were the biggest challenges in devising an in-depth biography of Ackles? One, obviously, is that many of his associates are no longer around, or impossible to trace.

MB: That’s certainly true. Also, associates, friends and family members I spoke to often simply couldn’t remember things. Or had recollections that contradicted the recollections of others. This is hardly surprising, as we’re talking about events that happened many decades ago. A good number of session players appeared across Ackles’s four albums, and quite a few are still around. But I accept it’s a tall order to expect anyone to remember what might have been just three hours of work one day in – say – 1969. Another challenge was that his recording career was short – covering about six years. About ten percent of his life. I had to think about how much focus to give to all those years before and after. I decided early on that I would devote most of my attention to those six years, and bookend them with briefer summaries of the before and after. And accept that there would be gaps in the story. And there are. I’m not claiming this is definitive.

Even not considering the idiosyncratic nature of his music, one of the most interesting aspects of Ackles’s career is the unlikely path he took to making records. He didn’t have an extensive background in, or even big passion for, folk or rock, although those are the audiences his record labels targeted. He didn’t even seem to have many aspirations to being a performer or recording artist. Although he wasn’t that much older than most pop and rock artists of the late 1960s, he was older enough that he almost might have been considered part of an older generation to most of the ones gaining attention in that era. He was first signed as a songwriter, and then got a recording contract with one of the best labels of the time, Elektra, as what seems kind of a fluke when it was determined he should sing and record his own compositions.

Reflecting on all of this, especially with your deep knowledge of the era’s singer-songwriting, does it seem like Ackles is almost unique in the way he became a recording artist, almost like it was accidentally through a back door? And could it partially account for how his work was so idiosyncratic?

MB: The way Ackles secured a recording contract was unusual, to say the least. Even singer-songwriters of a similar age to Ackles who started to make albums around the same time tended to have some sort of background that helps explain how they got to that point. I’m thinking of Fred Neil, for example, who had been knocking around the fringes of the music business since the late ‘50s. And Leonard Cohen, whose earlier creative life as an experimental novelist and poet gave him some counter-culture credentials, I think. Creatively, Ackles spent much of his twenties doing student and community musical theatre. I don’t really know what his ambitions were at this stage in his life. He said he always wanted to be a songwriter, but I could find no evidence that he recorded demos or approached publishers.

But he was writing songs, because when he bumped into David Anderle – an old college friend who had, conveniently, just started in A&R at Elektra – Ackles had songs ready to play Anderle. The various accounts of that meeting indicate that things moved very quickly, maybe even in one day – Anderle and Ackles met, Ackles played Anderle some songs, and Anderle signed him (or at least expressed an intention to sign him – no doubt that actual contracts came later). Without that chance encounter with Anderle, Ackles might never have got signed.

And then there was the added good fortune of being signed to a label run by Jac Holzman, at Elektra, who decided that Ackles should record his own songs after hearing some piano/vocal demos that Ackles recorded after signing as a songwriter. The label was still small enough and non-corporate enough for that sort of thing to happen, yet it was also starting to make some serious money from the Doors and others, so could afford to take risks. And Holzman’s position was that he could just decide to do something like that and it happened. He didn’t have to persuade anybody. He had control.

But I’m not persuaded that the manner in which Ackles got signed accounts for his idiosyncratic work. I think that comes from his unusual combination of influences, and also that he – not really a rock musician – was paired with producers and musicians from the rock world. For the first two albums at least. I’d suggest this led to a sort of creative tension which makes those albums so unusual. And then by the time he got more artistic control – arranging the third album and arranging and producing the fourth one – his own tastes prevailed, making those records just as unusual, but in a different way. In my mind there’s a definite divide there, between the two halves of his career.

In the 1960s, the music industry often had the mindset that some major songwriters should just be behind-the-scenes songwriters, rather than making records of their own compositions, especially if their voices and image weren’t considered as commercial as some artists who could interpret their work. As just a few examples, Randy Newman mostly wrote for other singers, actually with a fair amount of success, before doing albums; Carole King, of course, was largely a songwriter (with Gerry Goffin) for others before starting to make albums at the end of the decade; the first hit records of Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell songs were interpretations by others; Jackson Browne was only signed to an Elektra publishing deal, not a recording one, and didn’t make his recorded debut for a few years; Janis Ian told me Elektra only wanted to sign her as a songwriter and not a singer; etc.

Do you think Ackles’s timing, for all the bad luck his subsequent career might have suffered, was just right for getting a record deal, coming just at the time when people like Jac Holzman and others were realizing there was a market for songwriters with non-standard voices and images doing their own material?

MB: I think his timing was right, but it seems to have been more happenstance than intention. Elektra had already released records by David Blue, Phil Ochs, Tim Buckley, Fred Neil and Tom Rush by the time the Anderle signed Ackles. I think most of those artists fit into the “non-standard” voices category and were writing their own material. But, as we’ve discussed already, the difference with Ackles is that he doesn’t seem to have been trying to establish himself in that capacity before he got signed. He arrived at the right place at the right time, but it wasn’t planned.

Another unlikely aspect of Ackles’s emergence is that his first album was recorded with rock musicians, none of whom he knew, although he seems to have had no experience with rock, or particular knowledge of the form. But although the backing seems mostly to have been Elektra’s idea and arranging, it comes off pretty well, and not forced. Do you think Ackles simply had a musical talent, versatility, and personality that sort of made it easy for him to adapt to a new and pretty unfamiliar setting quickly?

MB: He was musically gifted and adaptable. Certainly, live tapes I’ve heard demonstrate that he could play and sing to a very high standard in that context. And everyone I spoke to commented on how congenial and friendly he was, so he would have been adept at getting on with people. But he also had a clear vision. There was a failed initial attempt to record that first album with Wrecking Crew musicians, and Ackles (and Anderle) decided it wasn’t working. He could tell – and articulate – when things weren’t right. That happened several times throughout his career.

The funny thing about that first album is that David Anderle said (to you, in fact) that a lot of it was pieced together and fixed in the mix, with the musicians playing to pre-recorded Ackles piano and vocal takes. And it really doesn’t sound like that. It has a loose, live in the studio sort of feel. So I think Anderle and (co-producer) Russ Miller deserve some credit.

I’m not trying to pat myself on the back too hard, but it was interesting to read that Jonathan Romney compared “Sonny Come Home” to the film The Swimmer in The Guardian. I regard that song as one of Ackles’s standouts. When I interviewed David Anderle about Ackles, I made that exact comparison, with no knowledge of that 1999 comparison in The Guardian. As you note in the book, Ackles couldn’t have seen The Swimmer before recording this, though it seems possible (I think unlikely) he read the short story on which it was based. Especially if you’ve seen The Swimmer (which I think is very good for the most part despite some dated elements), do you have any thoughts about the song and how it at least mirrors the spooky “empty desolate home” final scene of The Swimmer?

MB: I love The Swimmer. It’s a top ten film for me. I think the film and “Sonny Come Home” share two things. First, the arriving at what once was home, to find it’s all changed. Second, a general atmosphere of disorientation. But there are differences. The film follows the lead character, played by Burt Lancaster, as he makes his way home by swimming through his neighbors’ swimming pools. The arrival at the former home is the culmination of that journey. But in the song there’s no journey – it starts with ‘Sonny’ arriving at the now-changed former home. A related difference is that in the film there’s a creeping sense of something being not right that builds as the film progresses. But in the song the disorientation prevails from the start.

In his concerts, Ackles performed solo on piano, not with a band. This wasn’t unusual among singer-songwriters of the era, perhaps for financial reasons; Donovan and Simon & Garfunkel used few onstage backup musicians in their early years, Carole King, Randy Newman, and James Taylor performed solo on their early-‘70s BBC TV concerts, and I’m sure there are other instances. Although Ackles’s concerts seemed to be well received, do you think that live approach might have restricted his chances to break out into a wider audience?

As far as I could discover, Ackles played live with a band just once. This was when he visited the UK in 1968 and played with a pick-up band of bass, drums, organ and guitar, who approximated the arrangements on the first album. They recorded BBC radio and TV sessions, and played lived at least twice (once, a sort of private press function, secondly, on a shared bill at Fairfield Hall, in Croydon). Apart from that he played solo, as you say. And I think that did come with limitations, because he wasn’t a good fit playing to bigger rock audiences. He tended to play small theatres, clubs and coffeehouses, with correspondingly small audiences – maybe a couple of hundred people per night. If he’d had a regular live band he could have toured supporting rock acts, to far bigger audiences.

And it wasn’t just that he was a solo performer. He was a pianist, and in an age way before digital keyboards there was no way he could transport a decent-sounding instrument to gigs. This meant he was dependent on whatever instrument the venue happened to have. And if it was a poor-quality instrument, there was a corresponding impact on Ackles’s performance.

But I think another factor that limited the impact of his live work in terms of building an audience, is that he didn’t want to go out on the road and tour in the conventional sense. He said quite early on, in several interviews, that he didn’t want to do an endless run of one-nighters. So, I suspect that winning an audience through relentless live work was never going to happen, even though he played a fair number of shows.

Because Ackles didn’t sell a lot of records, it’s a bit of a surprise to learn from your book that he actually did a fair amount of concerts, though he favored residencies of sorts at certain venues, like the Main Point in the Philadelphia Area and the Canterbury House in Michigan. It’s nothing like Nick Drake, who did barely any concerts and seemed not to enjoy doing them, or Skip Spence, who didn’t do any as a solo act as far as I know. Ackles also seemed fairly at ease at his shows, with some audience repartee – nothing like the stereotype many have of cult singer-songwriters. Did this live activity also come as a surprise to you, especially as you were able to access tapes of some of those live concerts?

MB: I was surprised that Ackles played live so much. I don’t know how many shows he did between 1968 and 1973, when he was recording, but it must have been in three figures. For example, I know of four residences at the Troubadour in Los Angeles (one supporting Joni Mitchell, one supporting Elton John, one headlining and one sharing a bill with Dave Mason). That alone amounts to more than twenty shows.

I’m not sure that he was particularly at ease playing live, though. Or at least, he was often not at ease. His wife, Janice, said he was a nervous performer and sometimes got ill before shows. I’ve heard two tapes of him playing live at Canterbury House. On both his musicianship – his playing and singing – is superb. And on the second there’s a lot of good-humored chat with the audience between songs. But by the time that tape was made Ackles had played several shows at Canterbury House, and felt at home. Reviews of earlier shows at Canterbury House comment on his apparent nervousness.

Over the course of his four albums, Ackles moved from the vaguely folk-rockish backing of his first LP to increasingly theatrical music with looser ties to folk and rock, and eventually not many ties to folk and rock. Do you see this as him managing to circle back to the style he truly loved the most; a natural progression as his songwriting and studio experience evolved; or some combination of such factors?

I think the musical theatre influences were there from the start – see “Laissez-Faire,” “Sonny Come Home” and “His Name Is Andrew” on the first album. But they were partly disguised because the songs were performed by rock musicians playing rock arrangements. As you say, the albums became progressively more theatrical thereafter. I see this as a process of Ackles gradually getting more control of his recordings and pushing them in the direction he always wanted to take. The sound and feel of the third album, American Gothic, is as much to do with the arrangements – which Ackles wrote – as the songs themselves. I think the title track of that album, for example, would “feel” a lot less theatrical if the first album’s band had worked out some parts and performed the song.

Getting back to the process of what you wrote and researched, what were the most interesting and surprising things you learned, even having come into the project with about as much knowledge about his background as anyone?

MB: I knew before starting that there had been aborted attempts to record the three Elektra albums, but I hadn’t appreciated the stature of the musicians and arrangers Ackles worked with, unsuccessfully. Lots of Wrecking Crew players, Al Kooper, Don Ellis, Del Newman. People at the top of their game at the time. Yet it seems that Ackles was quite assertive in deciding that things weren’t working and insisting on moving on. That tells me he had a strong artistic vision from the start.

Similarly, I knew that he worked on musical theatre projects after his recording career ended. But I didn’t know the extent of that. To write a complete musical theatre play, with twenty plus songs each and a full script, must be a huge undertaking, and Ackles did it at least twice, as well as lots of other projects that didn’t progress so far. He chipped away at that work for decades, up until the end of his life.

As you note early in the book, many figures who worked with and knew Ackles are dead or untraceable, or might not remember much or anything about him even if you found them. Who were the associates you would have been most eager to speak with had you been able to, and why?

David Anderle, definitely. He knew Ackles before and at the start of his recording career, so would have had some unique insights.

You unearthed a lot of positive print reviews of Ackles’s records, some of which are almost shocking in the intensity of their praise, comparing his work to Sgt. Pepper in its quality and scope, for instance. Different reviews called American Gothic “the best pop album ever made…or maybe the second best,” and “the best album of the year? Undoubtedly. The best of the decade? Probably.” But as many such reviews prove, they’re examples of how even rave reviews don’t necessarily sell records. That happened, just drawing on a biography I’ve done, with the Velvet Underground’s records (more so near the end of when they were active) and John Cale’s first solo album. What do you think was preventing Ackles from breaking out to a wider audience – not just James Taylor or Joni Mitchell stardom, but even more modest sales that could sustain a career, like for Randy Newman and Leonard Cohen?

MB: Overwhelmingly, the main reason was the rock audience’s unfamiliarity with the styles and conventions of musical theatre, which came to dominate Ackles’s albums. I came across quite a few people who bought American Gothic on the strength of the reviews and were somewhat baffled by it. I think I was when I first heard it. Not that they, or I, didn’t like it. It’s more a sense of not really understanding what’s going on. There are some country-influenced songs that fit very loosely with the sort of thing people like Mickey Newbury and Kris Kristofferson were writing at the time (“Another Friday Night” and “Waiting For the Moving Van,” for example). But I can see why songs like the title track, or “Midnight Carousel” or “Montana Song” baffled people.

That aside, I think there’s a sense that, in terms of his character and persona, Ackles didn’t fit comfortably into what the music business or rock audiences expected at the time. I see something indefinably “rock and roll” about Leonard Cohen as a personality – even though he wasn’t a rock musician – that isn’t there in Ackles. And, after the first album, his songs weren’t widely covered.

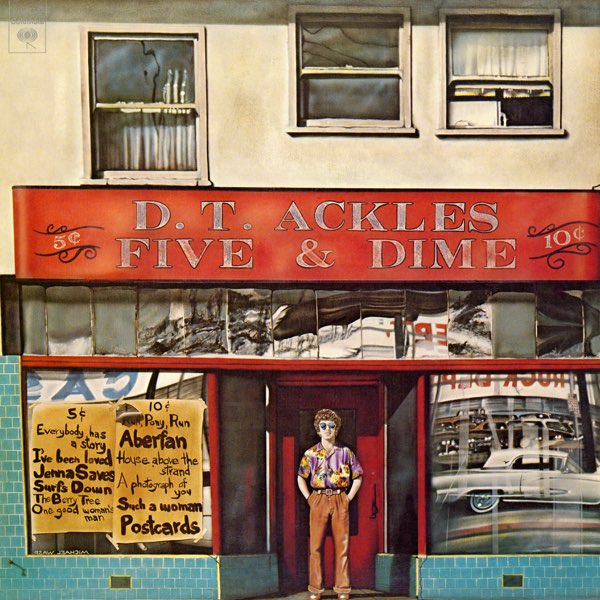

Then, toward the end of his career, he had some bad luck. After he left Elektra Clive Davis, an admirer, signed him to Columbia. But Davis was sacked while Ackles was recording what became his final album, Five & Dime, and at almost the same time Ackles’s manager dropped him without warning. These were events completely outside of Ackles’s control, but I think they finished off his career because he didn’t know anyone else at Columbia and he didn’t have a manager to advocate for him. If those two events hadn’t happened I feel certain that Five & Dime would have got more attention, and probably that Ackles’s recording career would have continued. And if it had continued, who’s to say he wouldn’t have eventually built up a bigger audience.

Something also apparent from the reviews you quote is that, even in the many positive ones, writers seem to be at something of a loss to fully describe or classify Ackles’s music, owing to its lack of familiar reference points. That led some of them to often use comparisons that might have been somewhat in the ballpark but weren’t totally apt, like to Randy Newman, Nilsson, or even Judy Collins. Could his elusive-to-classify style have been both a hindrance to his recognition at the time, and a reason he stands out now as more interesting in some ways than the many more conventional singer-songwriters of his era?

MB: Yes, to both parts of that question. I think most of the references writers used in the ‘60s and ‘70s when trying to place Ackles give some sense of him as a serious, song-based performer, with influences outside of those usually associated with pop and rock, while at the same time not really telling you what he sounds like. In addition to the names you list, other frequently-used comparators were Leonard Cohen, Laura Nyro, and Jacques Brel. And very often, there were references to Brecht/Weill. Musically, the Brecht/Weill comparisons are the most accurate, but I’m not sure how useful they are, or were then, as I suspect that Brecht/Weill’s work has never been widely known to your average rock listener, apart from a few cover versions (i.e. “Mack The Knife” by Bobby Darin; “Pirate Jenny” by Judy Collins; “Alabama Song” by the Doors).

Ackles’s biggest boosters were Elton John, for whom Ackles opened at John’s breakthrough 1970 concerts at the Troubadour in L.A., and John’s lyricist Bernie Taupin, who produced David’s third album. While that didn’t mean Ackles sold more records, what do you think were the biggest benefits of the Ackles-John-Taupin association?

MB: I think that connection is a big factor in helping ensure that Ackles retained his admittedly very modest corner in rock’s collective memory. Both Elton John and Bernie Taupin have taken multiple opportunities over the decades to talk about how much they admired Ackles. And the fact that Taupin produced American Gothic is of interest in itself, as we know him as a lyricist, not a producer.

For all the quality of Ackles’s work, for me personally, it’s not a surprise that he didn’t sell much, or even gain retrospective sales boosts and prestige like Drake and Spence did. The music’s just too theatrical and far from rock, especially on his later albums. What do you view as the reasons he hasn’t garnered a posthumous cult following on the order of someone like Drake’s? And do you see it as possible, even at this late date, that he could start to gain some more cult appreciation, and your book might help in that regard?

MB: In summary, I think there are three reasons. One – the unfamiliarity of his musical theatre influences; two – the absence of a tragic back story; three – the cancellation of the There Is a River box set [which almost came out in 2007]. But I think, with the help of a reissue campaign, he could get more attention even now.

Something that might have helped built Ackles’s career and visibility to a greater level was covers of his songs, which was probably Elektra’s initial thought in signing him first to a writing deal. To list just a few examples, some hit covers definitely boosted major singer-songwriters’ careers in their early days, like Three Dog Night’s “Mama Told Not to Come” for Randy Newman, Three Dog Night’s “One” for Nilsson, and Judy Collins’s “Both Sides Now” for Joni Mitchell. There weren’t that many Ackles covers. Personally I don’t hear a song that could have done this for him in this manner, though Julie Driscoll/Brian Auger & the Trinity’s “Road to Cairo” was about the best, and the best shot at doing so. Do you have any thoughts about why he wasn’t covered more often; what Ackles composition might have helped him via a cover; and what you think of Driscoll’s “Road to Cairo”?

MB: There were quite a few covers of songs from Ackles’s debut by established artists, in addition to the Driscoll/Augur version of ‘Road To Cairo’. Martin Carthy did ‘His Name Is Andrew’, and the Hollies and Spooky Tooth recorded ‘Down River’. And there were several other covers by lesser-known artists. But the covers tailed off for [Ackles’s second album, 1970’s] Subway To The Country, with Harry Belafonte’s version of the title track being the only one of note. This surprises me a little. I can see why something like “Inmates of the Institution” didn’t attract any other artists, but there are some quite simple, accessible songs on that album that are ripe for reinterpretation (for example, “That’s No Reason To Cry”).

But having said all of that I don’t see Ackles as a hit single songwriter, more a potential provider of album content. The Driscoll/Auger recording of “Road to Cairo” is a case in point. I think it’s a decent version, though there was talk of mastering and/or pressing problems that made the original single sound a bit weedy. But I can see why it didn’t repeat the success of “This Wheel’s On Fire,” the big Driscoll/Auger hit it followed. “Road To Cairo” is a story song – much of its appeal is in the unfolding narrative. The chorus “I’ve been traveling …” doesn’t have the rousing, catchy quality of “Wheel’s on fire, rolling down the road,” even though both songs share a similar brooding feel in the verses.

One of the greatest attractions of your book is that you were able to access, and describe in considerable detail, a good number of unreleased studio and live recordings. What were the most interesting of those to you, and what do you think they most revealed or added to his legacy that’s not apparent from his official albums?

MB: The unreleased recordings I heard – live, studio outtakes and demos – revealed to me that Ackles was prolific, and his standards were consistently high. Though he only made four albums (a total of 41 songs), he wrote dozens of other songs and the ones I’ve heard are all good. And I know I haven’t heard everything he did by any stretch. Among the most interesting to me is “There Is A River,” an outtake from American Gothic, which sounds something like a location recording of a street preacher. After he lost his deal Ackles worked on several musical theatre projects, including a contemporary setting of Puccini’s La Bohème. I’ve heard a demo of four songs from that project that, as you’d expect, deploy all Ackles’s musical theatre techniques. There are two ballads on that demo – “Mississippi Small Talk” and “Country Home,” that, to my ears, are the equal of anything he released.

You note that some of that unreleased material came very close to coming out in 2007 on the There Is a River anthology, though the circulation of advance copies means that a number of serious Ackles fans have been able to hear that. This of course is frustrating for serious Ackles fans, and finding out about quite a bit more unreleased material will make them yet more eager to hear more from the vaults. Do you see any possibility that unreleased recordings – both studio outtakes and the live tapes you detail – might come out in the future, and that your book might help with making that possible?

MB: One of my main hopes for the book is that it helps prompt a reissue campaign, and the release of previously unreleased material. There are fully realized studio outtakes from all three Elektra albums – both previously unheard songs and completely different versions of familiar songs. And I’d say there’s scope for a Live At Canterbury Housedouble album, which could include four previously unknown songs, alongside solo versions of songs from the albums. And there are all sorts of demos and other scattered live recordings for television and radio. There’s a lot of potential.

This is a very difficult hindsight question to answer, but had Ackles been able to make more albums, do you have any thoughts as to what directions he might have gone?

MB: I feel that if he’d been able to carry on and been given artistic freedom, he’d have done what he tried to do anyway – though without any backing – which is write, perform and record musicals.

The book hasn’t been out for long, but have you had any interesting reactions to it, including from people who might have known Ackles?

MB: So far people have been kind. I’ve had some touching emails from old friends and family.

To restate the cliché that’s on the verge of going viral: Q: Didja hear the one about David Ackles? A: Only a few thousand people bought his first LP – and none of them formed a band! (Boom-boom!) Do you see Ackles somehow becoming an influence, even a small one, on current/future musicians, as he was on you in your early musical career?

MB: I wouldn’t say Ackles was an influence on my early band, the Palace of Light. We loved his records, but I think we always understood we couldn’t get anywhere close to sounding like him, in any way. In fact, our record company suggested we cover one of his songs (“Postcards,” from the final album) and we declined. But I see no reason why he couldn’t influence contemporary musicians. I think that streaming – whatever anyone thinks about it – does allow people to investigate all kinds of music. And one consequence of that is that there are now lots of artists with very eclectic influences. Incidentally, my view on streaming is that the technology itself – like most technology – is neutral. I object strongly to the business model, as artists aren’t paid.