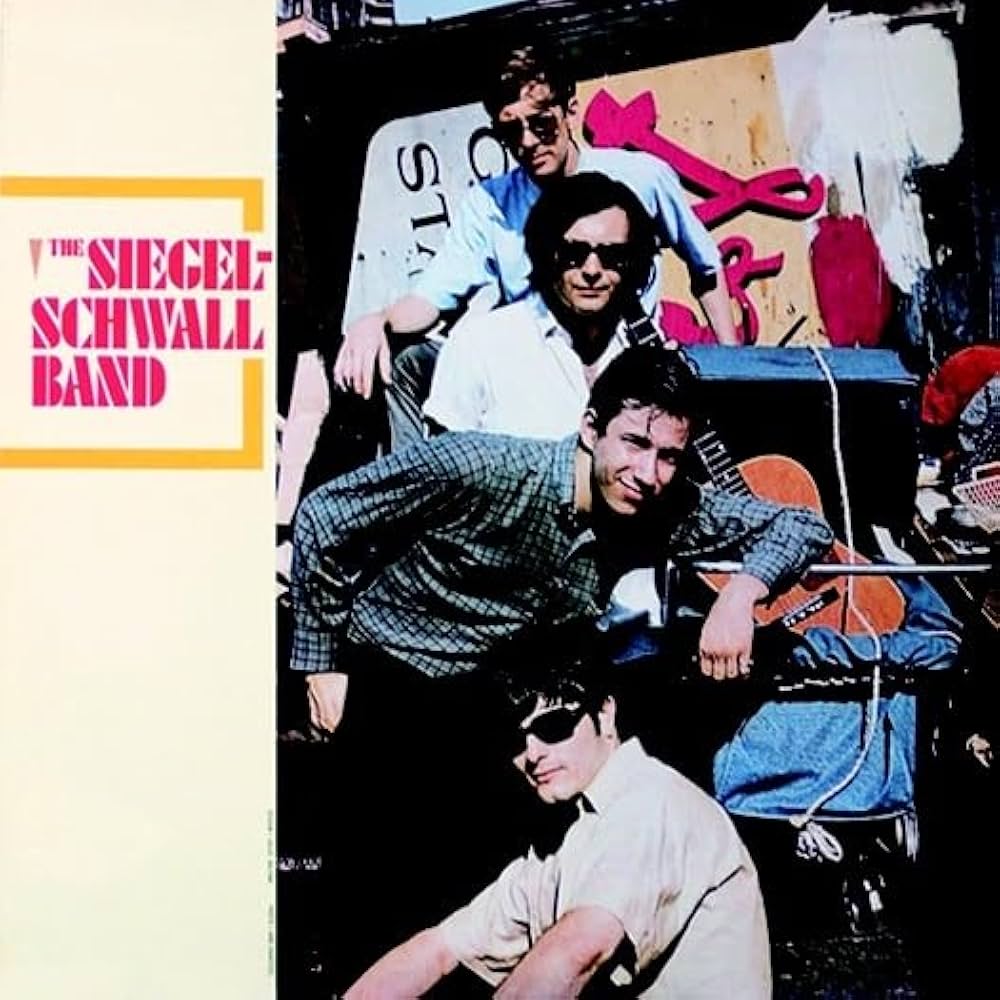

Joni Mitchell seldom recorded with other musicians in the 1960s, although virtually every other notable folk singer-songwriter was making the transition from folk to folk-rock in the last half of the decade. For many years, however, it’s been known that she did some recordings in Chicago with pretty full backup arrangements around late 1966. These were produced by Corky Siegel and Jim Schwall of the Siegel-Schwall Band, a white electric blues group with a style and repertoire similar to that of the early Paul Butterfield Blues Band.

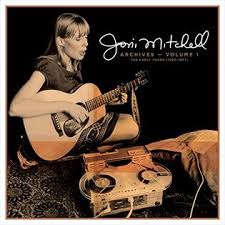

I was able to hear just a couple of these tracks about 25 years ago while researching my two-part history of 1960s folk-rock (now combined into one ebook, Jingle Jangle Morning). Recently, however, nine have gone into unofficial circulation. Some Mitchell fans wonder why none were included in her extensive and excellent Archives Vol. 1: The Early Years (1965-1967) box, which has five CDs of unreleased material predating her 1968 self-titled debut LP. Part of the answer, as well as part of the more important answer as to why she didn’t record with folk-rock arrangements in the 1960s, might lie in these tracks, which don’t match Joni with the most suitable backup that could have been devised.

On paper, this was a strange matchup for what was one of Mitchell’s first ventures into a professional recording studio, and possibly her first with what might have been called band backup. For all her eclectic talents, Mitchell didn’t do straight or loud electric blues, as the Siegel-Schwall Band did on much of their four 1966-70 albums for Vanguard. Their first, self-titled LP, issued around the time 1966 was turning into 1967, might have already come out when Siegel and Schwall produced these sessions.

There isn’t any blues on the music they produced with Mitchell. Perhaps more surprisingly, some classical and non-rock/non-blues instrumentation was employed. That’s not such a surprise if you know that after the Siegel-Schwall band split, Siegel fronted Corky Siegel’s Chamber Blues, which performed an unlikely blend of blues and classical music. It made for an odd mixture, to say the least, when Mitchell taped these sides in Chicago. The sessions were arranged, according to an interview Siegel did for jonimitchell.com, after Mitchell and her first husband Chuck (then playing at least part of the time as a duo) opened for the Siegel-Schwall Band in Detroit at the Chessmate club.

According to Siegel, the sessions took place in Chicago at a place actually called Eight Track Studios. He believes Josh Davidson would have been on bass, and seemed uncertain in his jonitmitchell.com whether the drummer might have been Jack Cohen and/or Russ Chadwick.

“We felt, artistically, it would be interesting to approach with a little bit of a classical flavor,” Siegel told me in 2001 when I interviewed him for my folk-rock books. “Jim Schwall mostly provided this touch with his string and brass writing, which was really great stuff, way ahead of its time for bringing classical idiom into folk and pop. There was violin, trumpet, drums, bass, and cello. Two of the pieces were by Joni and the other two were performed and written by [her then-husband] Chuck Mitchell. With regard to other aspects of the arrangements, which were more my effort or fault, you could actually see the bell bottoms and the paisley and maybe even some white go-go boots.” Although Siegel only referred to two tracks having been taped with Mitchell, nine identified as originating from these sessions are in circulation, and seem likely to be from the same sessions given the similarities of sound and approach.

The problem was that the backup arrangements didn’t mesh well with Mitchell’s material, though Joni’s vocals were fine. Certainly the songs were okay-to-excellent, including one that would appear on her debut album, “Night in the City” (done in two different takes and a backing track in Chicago) and another, “The Circle Game” (in two different takes) that would appear on her third, 1970’s Ladies of the Canyon (and had been covered by several artists by the time that LP was released). Although Mitchell didn’t put “Eastern Rain” on one of her albums at the time, Fairport Convention did a fine version on their second album with Sandy Denny on lead vocals (and Mitchell’s own live and radio performances of the song are on Archives Vol. 1).

Also done at the sessions were the enjoyable, lightly jazzy “Brandy Eyes,” a live November 1966 performance of which is on Archives Vol. 1; “Blue on Blue,” which recalls songs from her debut like “Michael from Mountains,” but is less distinctive (a March 1967 radio broadcast performance is on Archives Vol. 1); and “Daisy Summer Piper,” a lilting, lighthearted number with some hints of the irregular rhythms she’d use more often as time went on. The last song isn’t on an official Mitchell release.

It’s hard to say whether these demos put Mitchell off recording with a band, or even session musicians, for a while, but you could certainly imagine that being a factor. The backup players don’t seem to know the songs well, or play them with sympathetic complementary rhythm. Sometimes the blend of light folk-rock of sorts with horns and violins is exceptionally awkward. I’m not the fussiest audiofile, but the volume levels and mixing are sometimes notably clumsy and ill-judged. Going through these individually:

“The Circle Game” was lumbered with a squeaky trumpet fanfare and a plodding rhythm section, with no guitar presence to speak of. Someone, almost surely not Mitchell, was trying too hard to cram too much in, perhaps in a misguided attempt to sound like something that would catch the ear of AM radio programmers. Even by this point, “The Circle Game” was catching the attention of other recording artists, as versions would appear on 1967 albums by Ian & Sylvia and Buffy St. Marie, and on Tom Rush’s 1968 LP actually titled The Circle Game.

The different take of “The Circle Game” bundled with this batch, in contrast, is more suitably plain and folky. However, the voice that harmonizes with Mitchell on the choruses—it sounds male, and possibly it’s her first husband Chuck, who performed with her as part of a duo for a while in the mid-1960s—is unnecessary. If there are going to be harmonies this early on, let Joni double-track herself. Maybe that is Joni providing the wordless, ghostly background wails in the latter half of the recording. It seems like there are two guitars, but no other instruments.

The track identified as take 1 of “Night in the City” is downright strange compared to the locked-in easygoing swing of the re-recording on the first album (Joni Mitchell aka Song to a Seagull). It’s too fussily arranged, with a violin, cello, mandolin, and a chorus that breaks into a rhythm falling somewhere between polka and square dance call. Whether live or overdubbed, the rhythm’s erratic enough that she seems to have occasional trouble coming in at precisely the right time with her vocals.

The rhythm gets more waltz-like on take 2, though again it’s overorchestrated, and awkwardly shifts between the different rhythms of the verses and choruses. The drumming is rudimentarily clunky enough to make you wonder if the set is being handled by someone who’s not too experienced on the instrument. There’s not much to say about the instrumental backing track of “Night in the City,” though it perhaps inadvertently makes some of the mistimings stand out more, and you can clearly hear what sounds like faint accidental drops of objects at one point.

“Blue on Blue” is less excessively produced, though the orchestration is again unnecessary, if less blatantly obtrusive. Some of the guitar flourishes, whether played by Mitchell or someone else, recall those heard on early tentative folk-into-rock recordings by the likes of Tom Rush and Tim Buckley. There are more noises that sound like someone faintly fumbling with objects near the end, though Joni’s vocal is excellent, and a decisive cut above the standard of whoever’s been enlisted to help out.

“Eastern Rain” might be the best, or at the least the least ill-suited, of the productions for these demos. The guitar sounds yet more specifically like some of the rounded full high notes you hear on some early Tim Buckley records. The combination of that guitar, bass, and washes of what sounds like it could be a tabla fill out the arrangement. Like “Night in the City” and “The Circle Game,” this was certainly a song strong enough to have deserved a place on her first couple official albums, and again Mitchell’s vocal is first-rate.

Those tabla or tabla-like washes are similar enough to the ones heard on Fairport Convention’s version that one wonders if Fairport actually heard this exact Mitchell demo. They certainly did hear some Mitchell demos of songs she hadn’t released as they began their recording career, which they were able to access via their producer, Joe Boyd, as early Fairport member Iain Matthews told me in an interview.

“Daisy Summer Piper” likewise isn’t as overproduced as “Night in the City” and “The Circle Game,” though there’s light bass and drums, and high trills that sound like they might be coming from a mandolin. It’s a little odd that it was chosen to demo when at least one quite superior original composition, “Urge for Going,” is known to have been written by 1965, and somehow overlooked for this session. Maybe Mitchell herself doesn’t rate “Daisy Summer Piper” too highly, as it didn’t find a place in any guise on Archives Vol. 1. At least one other version, performed only with acoustic guitar accompaniment, survives as part of a group of demos she taped around this time the publishing company she had with Chuck Mitchell, Gandalf.

Mitchell would play more and more piano on her albums as her recording career progressed, but “Brandy Eyes” is the only one of these tracks on which the instrument is prominent. The bass and drums, however, are on the pickup band level, or worse. Maybe it’s Joni on piano, as you’d think she’d want to play something on each of the demos, though it’s not known for certain.

It’s hard to believe Mitchell was too pleased with these demos, or too confident it would help in getting a satisfactory record deal, although in his jonimitchell.com interview, Siegel says “she was really happy with it and really excited about it.” She was virtually certainly referring to these sessions in a March 1967 interview with Philadelphia radio DJ Ed Sciaky, where she remarked, “I made the mistake once of orchestrating [“The Circle Game”] and getting a blues band…who are also fine classical musicians to do an arrangement…And I tried to do a rock version of it and I lost everything. It’s strictly a ballad…If you put a rock beat to it, it would really, really be a hit, but it doesn’t work.”

That didn’t keep several other artists from trying to cut folk-rock

versions of “The Circle Game.” But Mitchell told Sciaky that in her estimation, “It didn’t work out well because ‘Circle Game’ is not ever going to be a rock ’n’ roll song. Ian & Sylvia found that out with their version, and I tried to do the same thing. It has to be kept down. It has to be a ballad. It’s very tempting.”

Perhaps a folk-rock approach would have worked out better than Mitchell’s Chicago demo session with more accomplished and sympathetic musicians. Bruce Langhorne, for instance, met Mitchell around this time, and recorded with more folk-rock singer-songwriters than just about anyone back then, including Bob Dylan, Richard & Mimi Fariña, and Fred Neil. Yet he feels her music sounded better unaccompanied for a reason: “I was used to just tuning into people and playing their material. And Joni—I couldn’t really play with her. Because she was so creative and so wonderfully unpredictable, and her music was so sophisticated, that I couldn’t just tune in and start playing and have it work.” Although Mitchell’s most renowned for her songwriting and singing, her guitar tunings were so numerous, complex, and unusual that these alone would have presented more challenges for accompanists than the usual singer-songwriter.

Throughout her career, Mitchell was so determined to call the shots for her music that it’s difficult to imagine she’d be put off playing with other musicians from one disappointing group of sessions. It’s more likely that she simply determined her early songs sounded best as acoustic solo performances, maybe with some encouragement from David Crosby, producer of her first LP. In the Crosby documentary Remember My Name, he noted that despite some technical issues he and Mitchell were dissatisfied with, he feels the record did capture “her essence.”

That can’t be argued with, given the quality of Joni Mitchell aka Song to a Seagull, whose hushed ambience I love. It’s still intriguing to consider what those songs, or any batch of her finer early songs, might have sounded like had a folk-rock approach been taken for her debut album. There’s a hint in a December 1967 televised performance for the Canadian Broadcast Corporation, where a song from her first LP, “The Dawntreader,” is given a backing track quite different from the studio version. Its lightly echoing electric guitar, basic drumming, and orchestration are much more tasteful than what was employed for the Chicago demos.

While such a thing probably wasn’t commercially possible back in 1968 (certainly for an artist making her debut on a major label), and is still rare today, it’s tempting to imagine her doing two albums of the same songs—one virtually entirely solo and acoustic, as she did, and the other with a light folk-rock approach. That’s something that can only exist in an alternate universe, if you believe in such Star Trek-like things.

Something that is evident, even from the Chicago sessions, is that Mitchell’s best material, and how it was sung, was so good at this early stage that it’s hard to believe she wouldn’t get a recording contract for another year or so. That’s also demonstrated, in better settings, by the wealth of recordings on the Archives Vol. 1 box set. Part of that delay was due to her insistence on a better deal than would likely have been offered to her earlier than when she signed with Warner Brothers. Fortunately much of what she did in the mid-‘60s before her debut album is now easily accessible on Archives Vol. 1, even if it doesn’t catch everything, and it’s unlikely the less impressive but revealing Chicago sessions will be granted official release.