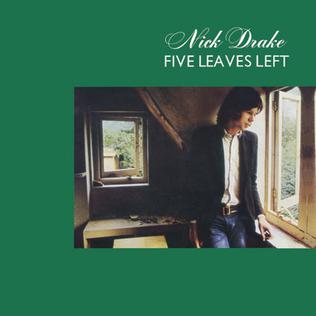

Nick Drake made just three albums, but now the archival releases of tracks unissued in his lifetime far exceeds those three LPs in quantity. The amount of archival material increased substantially in 2025 with the four-CD box set The Making of Five Leaves Left, three CDs of which (containing 32 tracks) were previously unissued. These three discs feature studio outtakes, most of them alternate versions of songs from Five Leaves Left, spanning late winter 1968 to early spring 1969, along with eight songs from an informal 1968 non-studio tape in arranger Robert Kirby’s Cambridge dorm room that’s of fairly low but listenable fidelity. The fourth CD is Five Leaves Left itself, Drake’s 1969 debut album.

Although the differences between the studio outtake versions and those heard on the final LP are usually not huge, it’s pleasant and interesting to hear the songs in somewhat different arrangements that are usually less elaborate than those on Five Leaves Left. Like many such historical boxes, these do illustrate how polish and production touches elevating the final versions to substantially higher quality. An early take of “‘Cello Song” (then called “Strange Face”) stands out with its absence of cello and inclusion of what sounds like steel drum patterns, perhaps played on piano. The early take of “River Man” doesn’t have the dramatic orchestration on the familiar Five Leaves Left arrangement, as another example.

As for songs that didn’t make the LP, “Mayfair,” which would be covered by Millie Small in 1970, is okay if perhaps atypical in its Donovan-ish upbeat observational flavor. Just three of the eight songs from the dorm room tape (“The Thoughts of Mary Jane,” “Day Is Done,” and “Time Has Told Me”) would make Five Leaves Left, though one (“Made to Love Magic”) would be recorded as a studio outtake in 1968. The other four are okay but not up to the same standard, again showing more of an early Donovan feel than his studio releases would exhibit. Drake’s skills on guitar—sometimes it’s hard to believe just one person was producing such a full sound—are in abundant evidence on most of the outtakes, even on the half-dozen tracks from his first studio session in late February/March 1968.

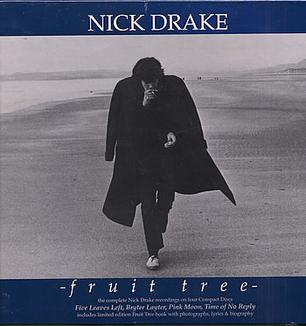

With an LP-sized 60-page booklet featuring extensive liner notes, production details, lyrics, photos, and tape box productions, the extras are elaborate. Note that a number of tracks recorded by Drake in the studio during this period, some of them detailed in the liner notes, are not included on this box. There’s no need to panic, as they’ve been available for decades on the Time of No Reply compilation and Fruit Tree box. Specifically, these are “I Was Made to Love Magic,” “Joey,” and “Clothes of Sand.”

The format design and art direction of The Making of Five Leaves Left was done by Cally Callomon, who runs the Nick Drake estate. I spoke to him about the box just after New Year’s 2026.

How did you get involved with the Nick Drake estate?

I met Gabrielle [Drake, Nick’s sister and well known actress] in ’95 when I was working at Island. I was at Island for ten years. I left Island in 2000 to go back to managing artists, which I’d done before, and designing for artists and musicians. I’ve always looked after Bill Drummond, so I wanted to concentrate on Bill’s career.

I suggested to Gabrielle that Nick never had a manager, and he could do with a manager. I think being an actor, she understands that more than others would. Because everything was down to her. Both her parents had died, so she was the last remaining Drake, with a very busy, hectic acting career. So it appealed to her to have somebody renegotiate contracts, which is what we first had to do.

Did you have any sense of how much material was available for the Making of Five Leaves Left box when you started working on it?

When I first started working on it, I had no idea there was this much material. I had tried over the years to find out what was in the Universal tape storage, and I got different feedback and data each time, because it was a mess. [When] they were getting their London-based tape storage properly into a digital library, suddenly it became easier then to put just “Nick Drake” into a database, and to find out what was there. I say that was easy, but Neil Storey [editor of the Island Book of Records series of books documenting the history of the Island label] was the person who had to do it. It’s not enough just to have data. You have to have an idea who was in the studio at Island, and at what time.

And because Neil was working on his Island Records book, his massive tome, he knew that in Sound Techniques [studio in London, where Drake’s producer Joe Boyd often worked], Nick was being filtered into various different hours whenever it was possible. So there may be something down that’s a Sandy Denny session, or a Fairport [Convention] session there, which actually turned out to be a Nick Drake session. Because someone had canceled, or they finished early, and Nick could get in there and do three hours recording.

So with all of these things, it takes a human being and previous knowledge to be able to filter it out. That was all done without me. That was something that Johnny Chandler [in charge of the box’s product management] wanted to do, because he wanted to find out, is there enough material for some kind of reissue program? He came to me nine years ago with “look, we’ve done all of this work, there’s absolutely no pressure on you to do anything about it.” He’d already paid Neil to do this work.

I didn’t think there was enough. I was astounded by how much there was, and I was really pleased to have the database. But there wasn’t anything in there that was saying this would justify a major release, or adding tracks, which we never want to do, onto stuff.

But I knew about the Beverley Martyn tape [with six songs, four of which would be re-recorded for the final album, from Drake’s first session at Sound Techniques in late February/March 1968; a copy came into the possession of Martyn, a singer-songwriter also produced by Joe Boyd]. I’d heard it some time before. So I said to Johnny, if we can get the Beverley Martyn tape, that would help.

Then in the process of doing that, I stumbled across – we investigated the Paul de Rivaz angle. [de Rivaz, like Drake a student at the University of Cambridge in the late 1960s, had the tape recorder on which the 1968 dorm room tape was made.] Because every couple of months, somebody would say, I’ve got a rare tape of Nick Drake, do you want to buy it? That happens quite often, and so much of the time it’s just a reel-to-reel recording of a bootleg that’s already been out on vinyl, and it’s very easy to work out what’s what. And there’s been some false generated…somebody making out that this is Nick Drake when it obviously isn’t. Not obviously, but you can tell that it’s not.

So it took some time for me to realize, we’ve got a lot of material, and we’ve also got some really special material. I thought then that the time was right to do what we did. It’s what we did with Family Tree [the 2007 compilation of pre-debut LP Drake tracks], to actually put it together in some kind of cohesive integrated formula. That suggested doing a separate standalone release, rather than adding any of the tracks onto existing releases. Or doing what Universal [who now own Drake’s catalog] often do with the deluxe packaging, just chucking in another CD of extra stuff [recorded] at the time. Johnny Chandler at Universal was the most honorable, patient and intuitive person to work with. So he removed any idea of pressure. Because they had certain [sales] targets they have to reach each quarter.

Did you have any idea of how much demand there would be for the box?

They knew that this would sell well. I always knew it would sell well. I had no doubt. No fear of that. Persuading other people – not Johnny, but other people – in different territories is very difficult, in America especially. Nick is held in very high regard as far as the media is concerned, and incredibly low regard as far as the industry is concerned. The two I think always play catch-up with each other on many, many artists, [singer-songwriter] Judee Sill and suchlike. You read more glowing reports about Dory Previn than you’d ever see comprehensive campaigns on her material. It’s a fan-media-based thing. I also mean film directors, television advertising, music supervisors and suchlike. They tend to lead the way.

There were a lot of multiple versions to choose from, as detailed in the table of sessions included in the box notes. How were the tracks that made the box selected?

I tried this on Family Tree. Really, the Everly Brothers’ [1968] Roots album [was] the guiding light for me. At that time of their career, they wanted to put a record out that showed the development from Tennessee right through to where they were then, which was a kind of slightly psychedelic country act. That album, which is a beautiful album, starts with them as children on a radio show with their parents. And it works its way through musically, tells a story. There have been a few albums like that. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band and the Dillards have been really good at that.

So I wasn’t inventing anything new with Family Tree. I wanted a radio program that starts with Nick in the [Mozart’s] Kegelstatt piece that he did with a classical trio, through the Molly Drake stuff [recorded by Nick’s mother], right through up until he was going to Cambridge. So I see this [box] as a follow on from that, when he put aside Bert Jansch and Jackson C. Frank and Bob Dylan, and had really the acceleration of him writing pieces of music that were the end of Family Tree. Things like “They’re Leaving Me Behind” [an early Nick Drake composition included on Family Tree] was just put aside, because he was writing so fast and so impressively that there was no need for him to have traditional material or covers on the first album.

[On the box], it isn’t all in chronological order. There’s some where you can hear a development between a very basic version to an experimental version to an orchestrated version, and the couple of dead ends that they went down. So it was trying to tell the story, with [producer] Joe Boyd very much and [engineer] John Wood at his side, trying to show the development. There was a deliberation of approach with John, Joe, and Nick that took them into completely new territory. You can hear Leonard Cohen in there, you can hear Tim Buckley for example. You can hear Beatles in there. But they were treading [a] very often less trodden path, I think most of the time.

What were the biggest surprises in the material you found?

“Mickey’s Tune” [on the de Rivaz tape] was a big surprise. Because when we first heard it, I didn’t know what it was. Nick just said…this is a nameless one, he called it. But I recognized the words. So it didn’t take me long to go back to the lyrics of the songs that never made it, never actually got recorded, to realize that that’s “Mickey’s Tune.” We knew he had a song called “Mickey’s Tune”; we had his handwritten lyrics. So there was the first recording we’d ever found of that song. I realized that’s why it never made the album, because compared to the rest of the stuff, it isn’t of the same caliber. They also thought “Time of No Reply” was not of the same caliber, which is what an abundance of riches they had, where you don’t even put that track out. [Although “Time of No Reply” was not on Five Leaves Left, a version from the sessions is included on this box.]

My thing that’s really revealing is the fact that the final album is all from the last session. [Seven of the ten final tracks were from the last group of sessions in April 1969, according to the documentation in the box’s notes; the other three were from the previous sessions on February 14, 1969.] So over a period of a year, they were going into the studio when they could, putting down more stuff. I think the fourth space in between sessions galvanized even more determination about what this album was going to be. That’s quite rare, particularly today, when people just think it’s alright to go in and everything’s done in one take, and put it all down and we’ll put the album out. I’ve got lots of favorite albums that took years to make.

I think it’s a testament to Boyd’s extreme faith in Drake that he and Nick took so much time for a debut album, a little more than a year, at a time when that wasn’t done for many artists.

I entirely agree. Joe is a very far-sighted man. He seems unaffected by fashion. You can tell by his dress sense.

Among the alternate versions, “Strange Face” is interesting since it evolved into “Cello Song,” a big part of the difference being different orchestration. On an early version, it’s hard to tell whether one of the instruments is a keyboard or a steel drum. Is it known what that was?

I don’t know, to be honest. There are a few recordings that Neil Storey has to suggest might be a particular conga player at the time. But not having proper track sheets of who was playing what, it’s all conjecture about what instruments were being played and who was playing them.

What do you think Nick gained most by taking so much time, when he sounded ready to record at the first sessions in early 1968? I think some other labels, artists, and producers would have been content to put out what he had at that point, since his songs, guitar work, and vocals were strong on less adorned arrangements.

I never met Nick. But from what I’ve learned from Gabrielle, he couldn’t be rushed into anything. But then he was also not in a position to rush into anything. Whereas Bryter Later [Drake’s second album, issued in 1971] was a more cohesive package, recorded as an album. And then it got delayed by nearly six months after its initial cited release date. It got delayed by quite a long time. I think Nick was impatient to get it out.

But that’s normal for someone who’s finished something that they’re immensely proud of following an album that really hasn’t set the world alight. It may have been thinking, with Bryter Later, well, this is gonna do it. This is far more direct. Nick didn’t know any better with Five Leaves Left, ‘cause he’d never released a record before. So he could easily just have been thinking, well, this is how long things take normally, isn’t it?

It seems like it took a while to settle on the orchestral arrangements he wanted. Was he trying to get something less fussy than some of the first attempts?

I don’t know the answer to that. I know he trusted Joe, because when Joe suggested John Cale [who contributed instrumentation to a couple Bryter Later tracks] later on, Nick wasn’t gonna say, well, no. It was, okay, let’s give John a go.

[For the first tracks attempted with orchestration], Joe suggested Richard Hewson [perhaps most known to rock fans for his work on some tracks on the Beatles’ Let It Be, as well as some for Apple Records releases by James Taylor and Mary Hopkin]. He wasn’t like a man of the moment, they could have gone with Reg Guest [who worked with Dusty Springfield and the Walker Brothers] or Wally Stott [most known for working on early Scott Walker albums] or any of the other key arrangers in London at the time.

But intrepid I think is the word I would always use. You take these steps and you see how they go. They both, Joe and Nick, knew these songs need augmentation. So how do we augment it? Which way do we go? Nick had already done this with Robert Kirby at Cambridge, and had been really happy with Robert’s work.

So hearing arrangements that both Joe and Nick didn’t feel were right, however competent and beautiful they are, gave Nick the permission to say, ‘I do have this other guy.’ Joe was about to spend a load of money on studio time with a string arranger he’d never heard of. I should say orchestrator; Robert never liked to be called an arranger. He said “Nick arranged the songs, I orchestrated them.” Which you hear on the Paul de Rivaz tapes; the arrangements are coming from Nick.

Nick seemed to be much more confident in his musicmaking than in other areas of his life. He was very determined to make records his own way.

I think it’s dangerous to mix confidence up with shyness. I know a few shy people who are very confident. It’s hard when I’m working with them to get over their shyness, and say look, what do you really think? Because you obviously really do think how you want this to be. The British in particular have a terrible habit of saying well Cally, I’m not sure about this. When in fact what they mean is, I don’t like this. Whereas Americans just say, I don’t like this. It’s so much easier. And the Irish. Working with the Cranberries, as I did for three albums, I knew exactly where I was at all times, with all four of them. Because the Irish are very direct speaking.

In England, we’ve got this dreadful habit of mealy mouth, working our way around – “I’m not sure,” or they use “kind of “or “sort of.” It’s a shyness, partly. It’s a need not to commit to anything. But Nick was a shy person. I think Joe and John got through that, and a few of the musicians that he worked with could tell when Nick was saying no, this isn’t working. That’s what [bassist] Danny Thompson would say. He was hearing the material for the first time; you can hear that he’s working out different bass arrangements. But he’d say he knew when it was right. He was getting enough feedback to say, well, these five different takes all work, but this is the one. But that’s just a personality thing. Because Gabrielle says [Nick] was a very stubborn boy.

The box doesn’t include any versions of “I Was Made to Love Magic,” “Joey,” and “Clothes of Sand,” which were all recorded at some point during the sessions the box spans. Was that because it was felt the quality wasn’t consistent with the other songs recorded in the studio, and/or because studio versions of all of these have long been available on the Fruit Tree box and the Time of No Reply outtakes/demos compilation?

I think it’s both. I’m really aware of giving people what they’ve already got.

I insisted that the final [Five Leaves Left] album is in there, out of respect to Nick. There are going to be a lot of people who are only just discovering Nick Drake. They’ve listened to maybe four or five songs by streaming the songs. This might be their introduction to Nick as a Christmas present, The Making of Five Leaves Left. I felt we had a duty to show people what the finished album ended up sounding like. That was my only compromise, really, of putting in something that had clearly already been sold. Some people found that bit hard – why did we bother with that? But it’s a bit like releasing something that’s just Rembrandt’s sketches, and not showing what the sketches turned out to be.

Five Leaves Left only sold about 2000-3000 copies when it first came out in 1969, although now, like all of Drake’s catalog, it’s sold many more. Do you know how many it’s sold at this point?

I have no idea. I’ve tried to find out worldwide sales figures. You move from one platform to another. [There’s] a different accounting procedure at Polygram to Island, [and then] into Universal. And very, very few people there are at all interested in historical sales. If it came to awards, all three albums would be silver and gold. They’ve reached those kind of figures worldwide. But I wouldn’t want to ever hazard a guess how many copies have we ever sold of Five Leaves Left.

[In the UK, all three of the studio albums Drake issued in his lifetime, also including 1972’s Pink Moon, have been certified as “gold,” signifying sales of 100,000 copies. The Drake compilations Way to Blue and A Treasury have also been certified as gold, and another compilation, Made to Love Magic, has been certified as silver, signifying sales of 60,000 copies. These figures only account for sales within the UK; the worldwide figures are surely much higher.]

There’s an interesting comment from Joe Boyd in the box notes that “Pink Floyd and the Incredible String Band had sold themselves, Sandy [Denny] with Fairport.” [Boyd also produced the Incredible String Band and Fairport Convention, as well as Pink Floyd’s first single.] Do you have any thoughts as to why it took Nick Drake so long to find his full audience?

Pink Floyd were a blues band. They fitted into the music of the time. They mixed with the cognoscenti, and they mixed with quite high-falutin’ people in London. They were middle class students in London. They had [the underground psychedelic club] UFO as a vehicle, and Joe Boyd as a vehicle. So they had a lot of the pieces all in place. They had Syd Barrett, very flamboyant, attractive, enigmatic soul. They played live a lot, and did interviews. And their music sounded like 1967.

People just loved Nick, ]but] I don’t think anybody wanted to go round championing him, even though Elton John was, who was unknown at the time. [In July 1970, Elton John even recorded four songs from Five Leaves Left as part of a demonstration album intended to generate other versions of songs by artists with whom Boyd was working.] He just didn’t have the network sorted out.

[Also] there was a snobbery at the time that you didn’t release singles. Or if you did release singles, they weren’t on your album because that was seen as commercial. He was with Island Records, who were one of the chief perpetrators of that. Jethro Tull singles would not be on an album.

It’s a lethal combination, but mainly I think it’s because Nick’s music, there wasn’t a template that it fit into. Lots of people loved the music at the time through the [Island] sampler albums, mainly. And that’s me. That’s where I first heard Nick. I couldn’t work out where this fitted in the Spooky Tooth/Traffic/Claire Hamill sort of territory within Island, but it just sounded great. It sounded like he was his own person, which he most definitely was.

There are a few artists that I think really are underappreciated. Even though Judee Sill has fans, and Dory Previn has fans, and David Ackles has fans, I still think they’re not as appreciated in the way that I think could be.

I would also put Sandy Denny in that category, at least in the US, where I’m from and based. She’s not nearly as well known here as she should be, and though some reissues have put out a great deal of her released and unreleased material, they haven’t always been that accessible.

I’ve used Sandy Denny, whose music I absolutely adore, as an example of how not to do it. Jeff Buckley is probably another example, where there are 29 different versions of Jeff’s only album. Because somebody else will say, oh, we can do it like this. And somebody says, yes fine, do it like that. So the more you do it, the weaker it becomes.

I feel Sandy has been betrayed commercially. If you’re gonna release a big box set for 120 pounds and say this is everything, which I love having, and then six months later reissue all of her albums with some instrumental tracks that aren’t on that box set, that to me is a classic case of a record company losing track of what it is to buy records. They now have to sell to the trade. They can go to the trade and say, six new tracks on this, and this has never been heard before.

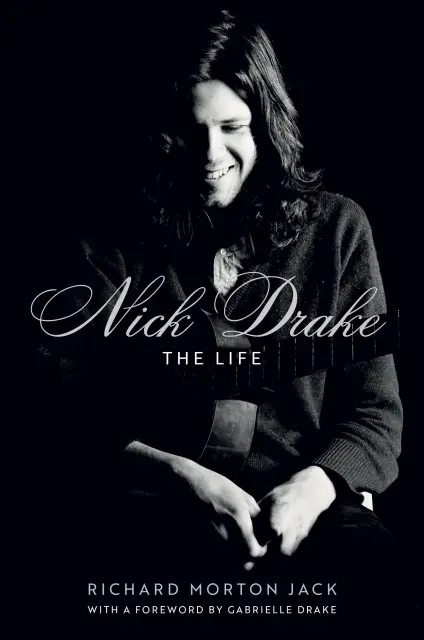

This is why Richard’s book on Nick Drake [Richard Morton Jack’s Nick Drake: The Life, issued in 2023] is so good. He writes with the reader in mind. And I wish some of the record companies would release records with the purchaser in mind.

I love the Beach Boys. I love Holland, that’s my favorite album. When this set came out, it was 80 pounds, Carl and the Passions and Holland together. The music is fantastic; I knew the music was fantastic. The book that comes with it is almost like a child’s pin-up book of photos of them playing live. Come on, it’s got to be better than that. With a story like Holland, why it happened.

My Scott Walker box set that I did [In 5 Easy Pieces, from 2003], I’m just ashamed of. Because I was pressured into putting out something that I thought was really, really substandard. It didn’t start out that way. But there was just a desire to get the thing out. That should be released—not when it’s finished, because it never is—it should be ready. Until you’re ready, just don’t put the thing out. But you just need one TV ad, and someone says quick, let’s get this out, because there’s an opportunity. That is losing sight of what it’s like to buy records, for me.

Fruit Tree [the Nick Drake box from 1979, with his three original LPs, at which time his cult following was just starting to build; this was expanded with a fourth disc of outtakes, Time of No Reply, in the mid-1980s] and the Sandy Denny box set [Who Knows Where the Time Goes, a four-LP set from 1985] had me in mind. I tried very hard to work out who had a box set like Fruit Tree before Fruit Tree. I thought this is tremendous, this is fantastic. For years, I couldn’t think of another artist that have had the same treatment. Soft Machine had Triple Echo [a three-LP set from 1977], but that was almost all unreleased Soft Machine material. I did find an artist who’d had this treatment. This was Roy Harper. Because there was a Harper box [the limited edition Harper 1970-1975] that came out that just put albums in, with Flashes from the Archives of Oblivion as an extra album inside. He’s the only person I can think of that had a box set done like Fruit Tree before.

When I worked with Julian Cope, he would say to be a Doors completist, you don’t have their last two albums, Other Voices and Full Circle [recorded and released after the death of Jim Morrison]. That’s what a completist is. I always took that on board is that having everything doesn’t mean it’s complete. It’s knowing what not to have (laughs). We all know several artists where you think, well, there’s Tim Buckley albums that you really don’t want in. The Rolling Stones, I’m very grateful for the fantastic records that they made, but to be a completist, my Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan collection ends at this particular time. And there’s enough there to keep me going for years.

Would it be a surprise to find enough similarly unreleased material to make a box or expanded edition of Drake’s second album, Bryter Later? That’s my favorite and Joe Boyd’s favorite, as well as many other people’s.

It would be a big surprise, but never say never. We would have to send Neil Storey back in. John Wood thinks it was done much faster in single takes. I’m not sure. It was eight-track, it was recorded as, so there’s a lot more scope in there. But it would take six months of Neil digging, and working out how many takes of “Northern Sky,” and how many takes of…It’s something we definitely will do, but whether it justifies a release or not [isn’t yet known].

There’s a BBC session we couldn’t include [on] Five Leaves Left. We wanted to, but the BBC just wanted too much money for it. We may go back in on that. And maybe someone will come forward and say I have got a recording of Nick on Manchester TV or whatever. Never say never.

But the way the [Making of Five Leaves Left] set is designed and put together I think justified four pieces of vinyl. Now if somebody said there is enough for a single piece of vinyl extra for Bryter Later, and we thought this is amazing stuff, it doesn’t have to be commensurate with The Making of Five Leaves Left.

I’m publishing my own books of traditional material, folk tales and such like. I work with Bill Drummond all of the time, and we have a number of projects for 2027 that we’re investigating on Nick, and talking to people about what we could do.