Lots of people, including myself, visit sites marking where the Beatles grew up in Liverpool. In fact, there are a number of tours that will take you around — the best by some distance is the one that goes into Paul McCartney and John Lennon’s childhood homes (https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/beatles-childhood-homes). A good number of people go to Elvis Presley’s birthplace in Tupelo, Mississippi, and of course tons go to Graceland in Memphis. No doubt there are some other rock landmark tours — it’s not official, but a fellow writer took me around to places in Belfast where Van Morrison grew up and mentioned in his songs.

But few people visit landmarks of the Rolling Stones’ early years. In part that’s because, unlike the Beatles, they didn’t all grow up in the same town. All but Brian Jones were raised in London or near London, Jones hailing from Cheltenham near the Welsh border. But London’s vast and the other four weren’t near each other. Except, that is, for Mick Jagger and Keith Richards, who both grew up in the London suburb of Dartford. That is, if you can accurately call this town of nearly 100,000 about a forty-minute train ride from the big city a suburb — more on that later.

Considering the Stones are (or at least were) the most popular group in the world bar the Beatles, and that Jagger and Richards were (and are) the most important members, it’s a little surprising there aren’t more pilgrims. There is, however, at least one operator of regular Stones-Dartford tours. I and a friend took it on a July Sunday. We didn’t have any trouble booking it — actually, we were the only two on the tour, the operator taking us around for a couple hours in his car.

I’d have to say that if you’re not a big Stones fan, you’ll be pretty nonplussed by the tour, which takes you around to a series of buildings that most would find nondescript if not for their Jagger-Richards associations. (And you do need a car to see them in a couple hours; Dartford’s not that big, but the sites are fairly spread out around town.) If you drag someone along who’s not pretty passionate about the band, they’ll likely feel kind of like I do when I tag along with friends looking at tapestries. But if, like me, you are intensely interested in their history, it’s worth doing, if only to get a sense of how utterly average Mick and Keith’s surroundings were until they helped form the Rolling Stones.

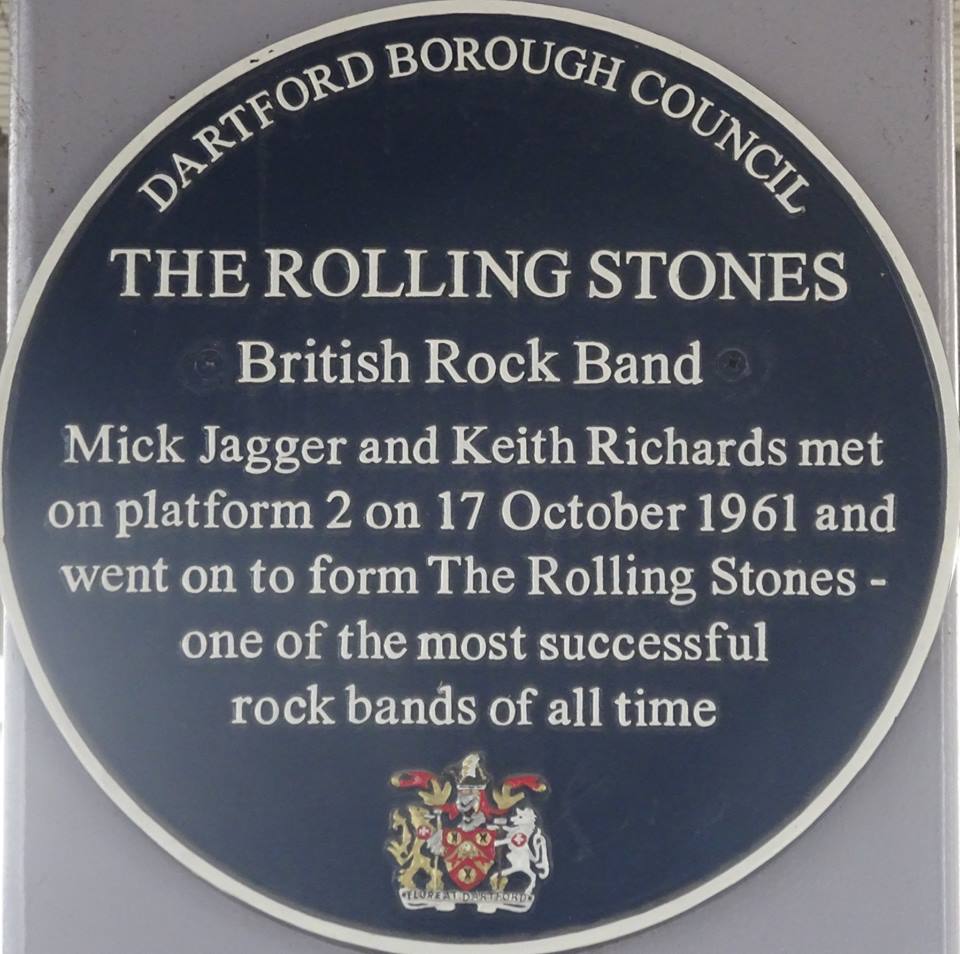

The most significant stop is actually the very first one, and something you can easily visit on your own if you wish. It’s the Dartford train station platform where the pair met on October 17, 1961, setting into motion the events that led them into the Rolling Stones. Indeed, the spot’s now marked by a blue plaque honoring its significance:

Sure, there’s not much space for explanatory text on these plaques, but it’s not quite accurate. Mick and Keith did know each other casually at various points while growing up in Dartford, and this didn’t mark the first time they met. And as I heard very quickly when I posted this picture on social media, many fans took exception to the plaque’s claim that they “went on to form the Rolling Stones.” In their view, it was Brian Jones, or Brian Jones and keyboardist Ian Stewart, who formed the band, or at least got together to form a band that Jagger and Richards joined very shortly afterward. I don’t find this important enough to argue or get upset about. I think that Jones, Stewart, Jagger, and Richards were all important in the initial stage of the Stones’ evolution, which was quite complicated and would see a number of people go in and out of the lineup until they settled on five members (not including Stewart) in early 1963.

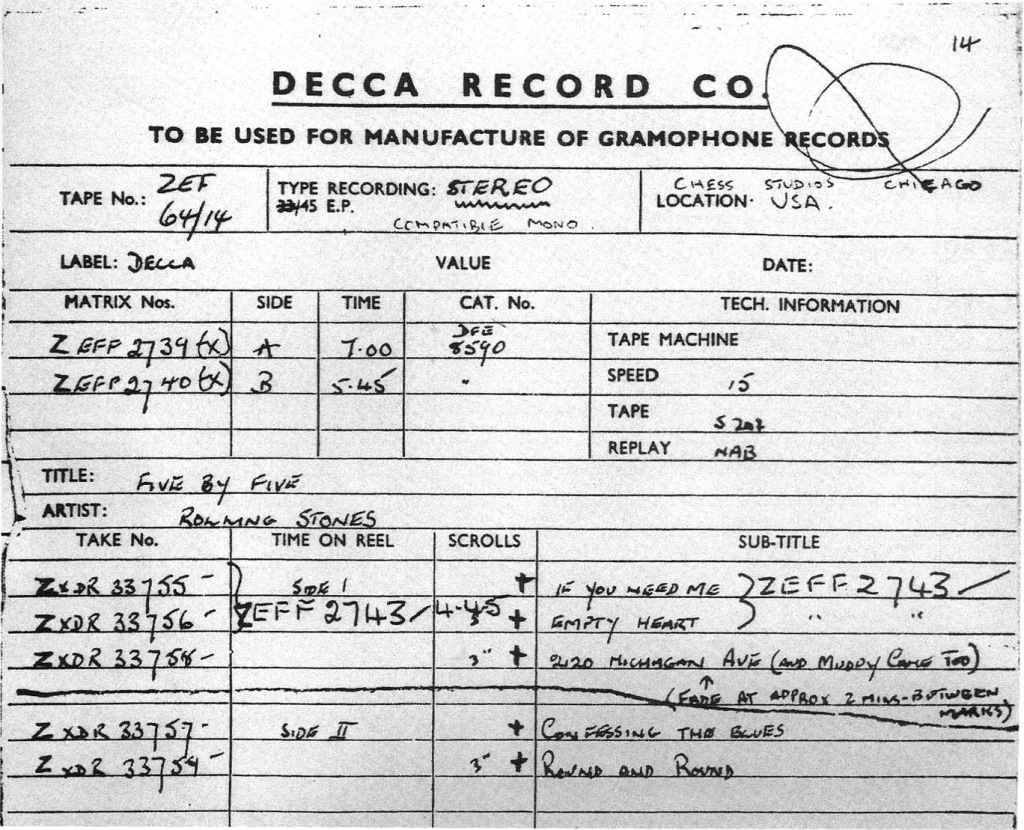

But this was the meeting that sparked Mick and Keith’s very close personal friendship and musical collaboration. The story’s pretty well known (even to some non-Stones fans), but after they recognized each other while waiting for a train, Richards spotted albums Jagger was carrying from Chess Records — a label that issued many records by some of their favorite artists, like Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, and Muddy Waters. That got them to discovering they had very strong common musical interests, as well as both knowing another budding musician into the same material, Dick Taylor (an original Rolling Stone, though he left by the end of 1962 to found the Pretty Things).

So yes, it was a momentous occasion well worth marking, though maybe not worth the hour and a half roundtrip train ride from London just for the plaque alone. Otherwise it’s an unremarkable train platform:

As a side note, only about ten days before taking this tour, I actually saw Dick Taylor performing. The Pretty Things have a lengthy, fascinating history that can’t be summed up in a paragraph (and there’s a whole big chapter about them in my book Urban Spacemen & Wayfaring Strangers: Overlooked Innovators & Eccentric Visionaries of ’60s Rock if you’re curious). Suffice to say they were the best British Invasion band never to make it in the US, and sounded much like a raw Rolling Stones in the mid-’60s, unsurprisingly as they drew from very similar influences. On July 13, 2018, I saw them give what was introduced as their last London club performance, with Taylor and original singer Phil May still in the band:

Dick Taylor (left) and Phil May of the Pretty Things onstage at the Half Moon Putney, July 13, 2018.

Of greater surprise to me, when I referred to Dartford as a London suburb in my social media posts, I quickly heard back from a couple British residents who took exception to this categorization. “Technically, Dartford has never been a London suburb,” wrote one. “It has never been part of any unitary authority centred in London (the LCC or its successor, the GLC) and it isn’t even part of the Metropolitan Police Area. Just why this is so, I can’t really say, any more than I can explain why Watford and Epsom were never included in Greater London for administrative purposes.” Another simply stated, “Dartford is in Kent, it’s not a London suburb.” Now, most small-ish cities/large towns twenty miles or so from one of the biggest cities in the world would be, I’d say, fairly described as suburbs, at least in the sense US residents use the term “suburb.” My main point, as I explained, is that Dartford is near but not part of London, a forty-minute or so train journey away.

Getting back to the Dartford train station, I’d guess the surrounding area has changed a lot since 1961. Walk over the road and there’s a huge shopping center. It’s as impersonal as its US counterparts, though a theater was staging a production based on the Rolling Stones’ biggest rivals:

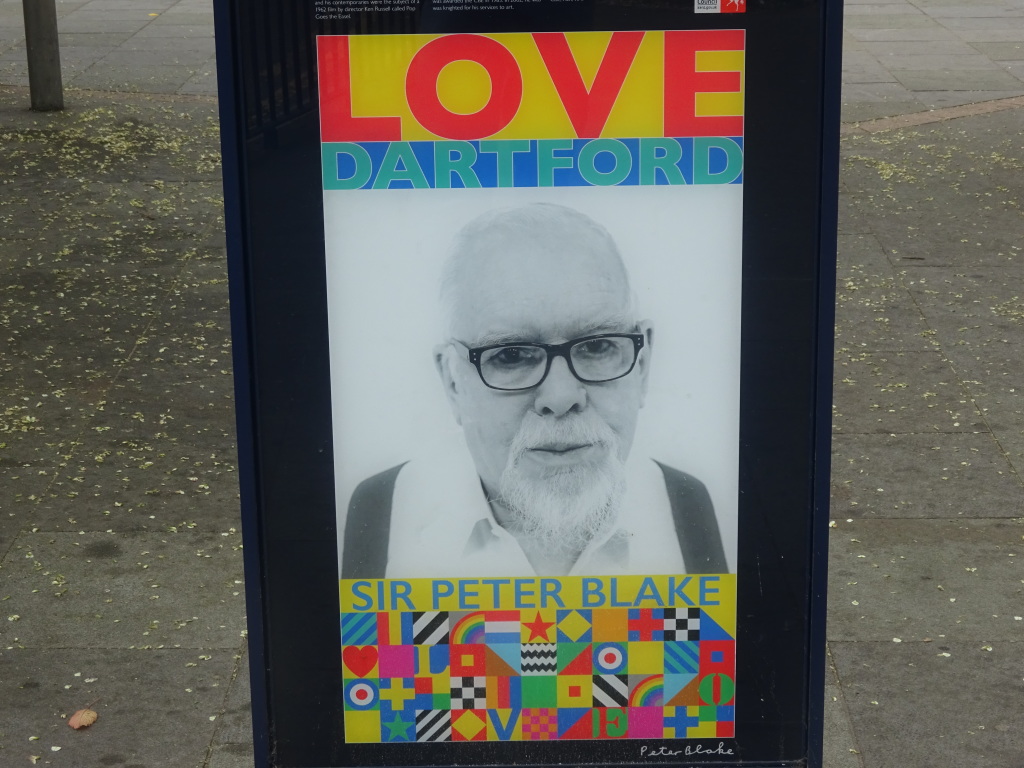

And Dartford being proud of whomever famous they can dig up who was also born in the town, there was a permanently mounted poster honoring artist Peter Blake, most famous for his work as a designer for the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper album:

Get a bit away from the train station area, and there are older buildings and less rampant modern development, some of which have strong Stones associations. Here’s the hospital where they were born, though as I remarked to the tour operator, it looks more like a doctor’s office than a hospital:

Then there’s the Holy Trinity Church where Mick was christened and Keith sang in the choir — actually quite an aged structure, with the oldest parts dating back to medieval times:

Cities don’t in general do much to honor living rock legends, and Dartford’s no exception. There is a statue of Jagger, but it’s way off the beaten path in the town’s Central Park. It’s so far along a path leading away from the park’s chief open space, in fact, that it’s not too easy to find unless you have a guide. The statue’s so slender that even within feet of reaching it, the sideways view makes it look like some piece of metal sticking up from the ground until you get right in front of it:

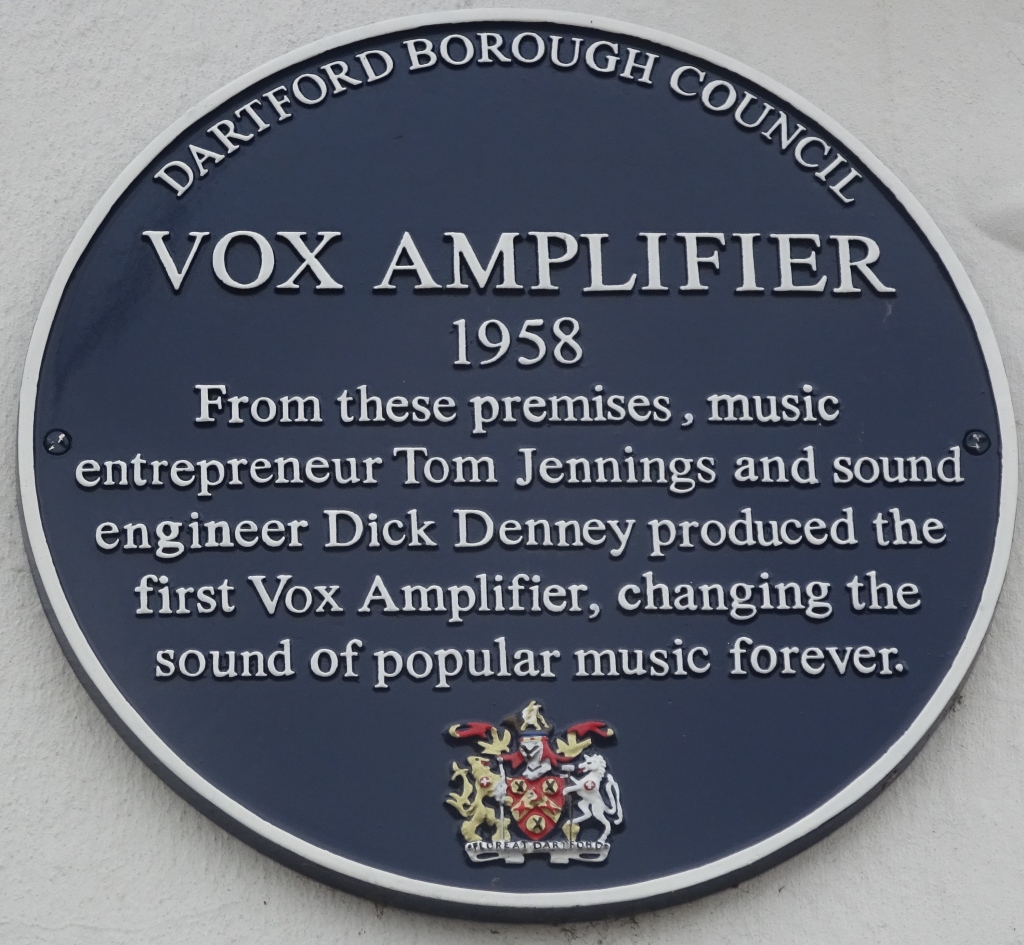

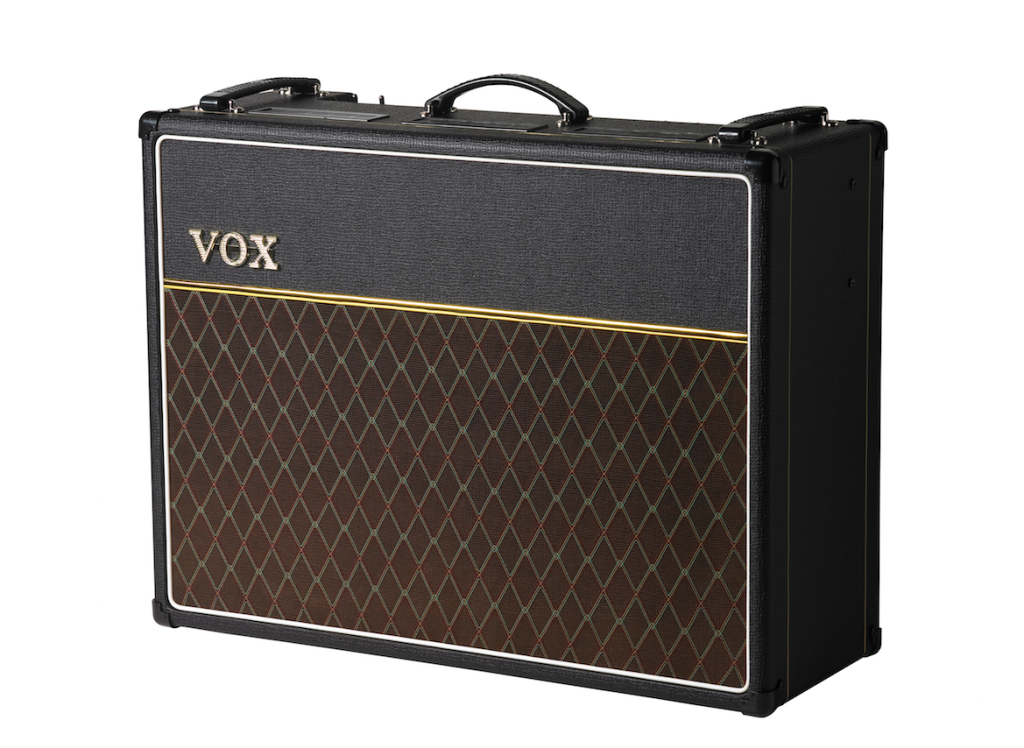

It’s not obvious, but the thing in front of the bench that looks like a small metal door is supposed to represent a Vox amplifier. Why? The answer’s revealed later in the tour.

Mick and Keith didn’t live in the same homes the whole time they were growing up, and the tour visits two former residences of each Stone. Here’s the earlier one for Richards, above a shop:

Unremarkable, certainly, except for a plaque marking its significance:

Rock god, sure. But “cult film star”? Is that really worth mentioning on a plaque?

It’s impossible to get a good clear picture, but inside the window of the store (which was closed it being a Sunday), there was a photo of Keith coming back to visit the building many years later:

The first of Mick’s childhood homes on the tour is just a couple blocks or so away. As Jagger and Richards were born just half a year or so apart, certainly they must have run across each other in the neighborhood. Mick’s building is yet less remarkable than Keith’s:

You could say the same about the nearby primary school they both attended for a while:

The next stop was Mick’s subsequent childhood home. It’s not that visually stimulating, but it does generate a little more thought. It’s pretty big — certainly big for a suburban London home for a family of four (Mick has a younger brother) in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Jagger’s final years in Dartford. His father was a physical education instructor, which isn’t a profession we associate with affluence, but the family must have had some decent income and resources. Or, at least, more than the Richards family, whose subsequent home (coming up later) was bigger than their earlier one, but not as big as this one. It’s a little like seeing the difference in size between McCartney and Lennon’s childhood homes — Lennon might have put “Working Class Hero” on his first album, but he definitely had a much bigger and nicer house than McCartney or the other Beatles had.

Part of the reason Mick and Keith didn’t know each other that well before their train station summit was that after going to the same primary school in early childhood, they attended different institutions. Jagger went to Dartford Grammar School, which now also houses the Mick Jagger Centre, a “multi-use facility holding a music venue, theatre, dance studio, meeting rooms and bar/café which are all available to hire on request,” according to its website.

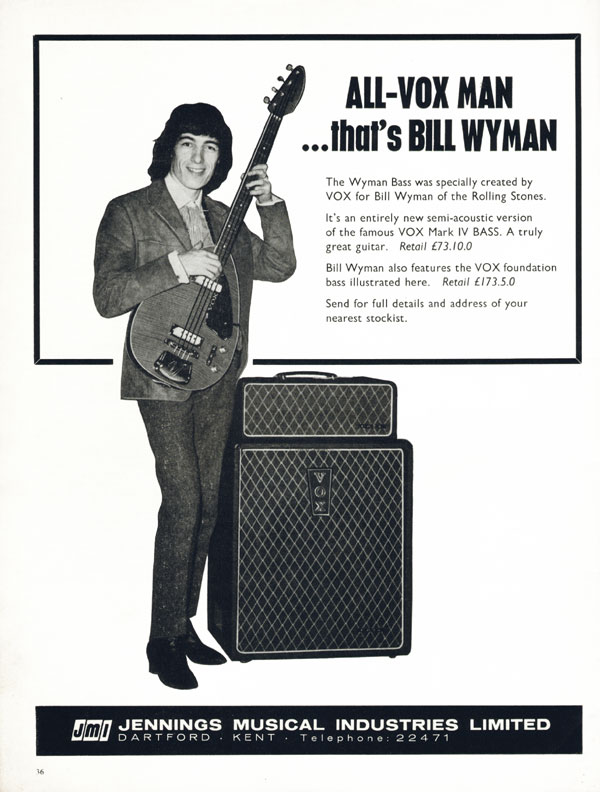

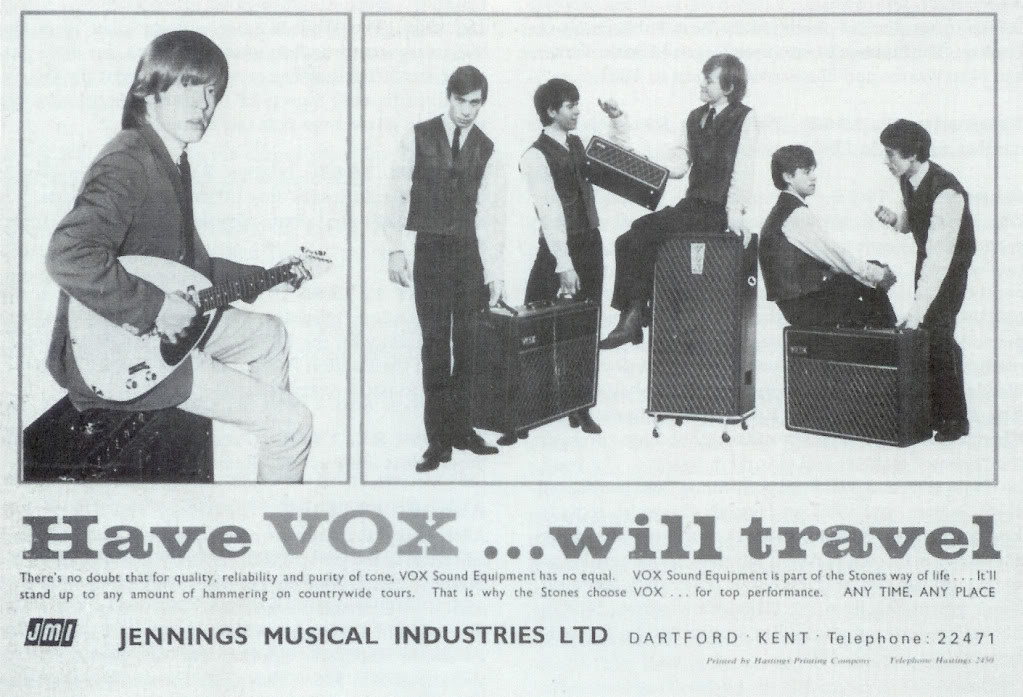

Just a few blocks away from Dartford Grammar School is an arguably more interesting structure. While Jagger was going to school nearby, a brand of equipment the Rolling Stones and many other ’60s bands used was being developed just a few blocks away, as the plaque on the building declares:

So that’s why there’s a Vox amp near the statue of Jagger in Dartford Central Park. It’s not a very big or impressive looking building, and is now occupied by an entirely unrelated business:

The last stop on the tour was Keith Richards’s other, later childhood home. Visually unexceptional, it does naturally have a plaque explaining its importance:

I’m well aware these photos don’t make for a stunning spread, or even one as interesting as other childhood homes of future heroes, like the ones of the Beatles or Elvis. What they do reflect, however, was how utterly ordinary a suburb Dartford was, and is.

When Mick and Keith were getting turned on to the artists of Chess Records, I imagine it must have fueled their hunger to see more of the world. Or at least something different and more exciting than the plain and predictable, if safe and secure enough, neighborhoods in which they lived and went to school and church. Going to Chicago, home of Chess Records and the greatest blues artists, wasn’t an option. But going to London was, and only a year or so after meeting on the train platform, Jagger, Richards, and Brian Jones were living together in a legendarily squalid apartment in the city’s Chelsea district, in Edith Grove.

As Robert Christgau’s chapter on the Rolling Stones in The Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll noted, “Only two of them [Charlie Watts and Bill Wyman] came from working class backgrounds…This is not to say the Stones were rich kids; only Brian qualified as what Americans would call upper middle-class. Nor is it to underestimate the dreariness of the London suburbs or the rigidity of the English class hierarchy.” (Hey, there’s another US writer referring, if indirectly, to Dartford as a suburb!) Rock’n’roll, soul, and the blues didn’t offer Mick and Keith a route from poverty; they weren’t poor, though Mick’s family seemed a lot better off than Keith’s. But it did give them a route out of the suburban lifestyle that Dartford certainly reflects.