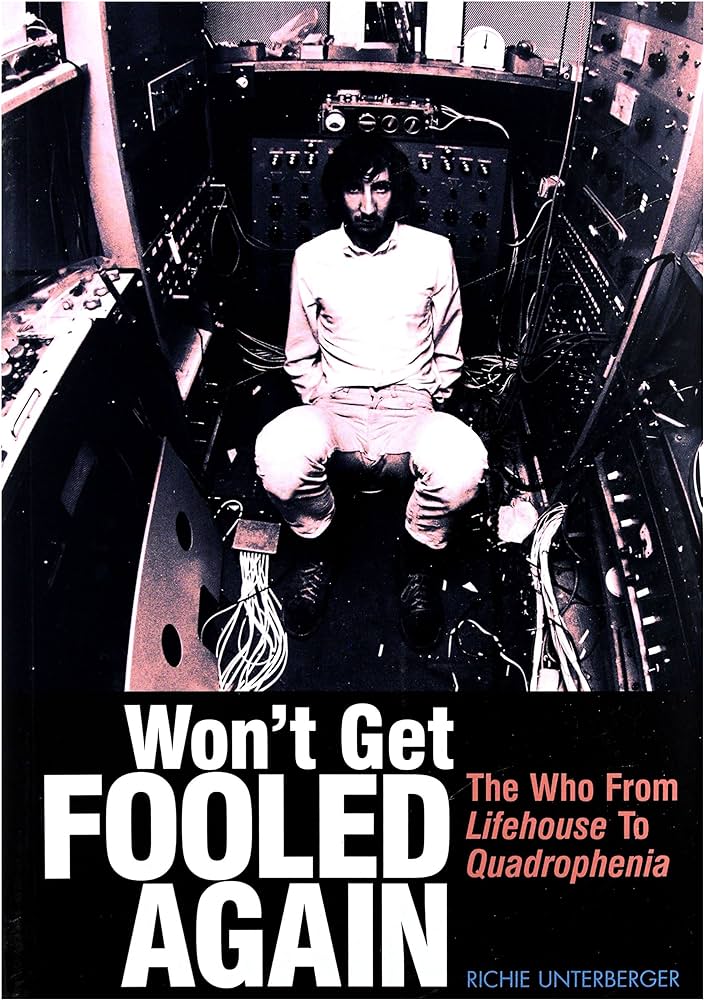

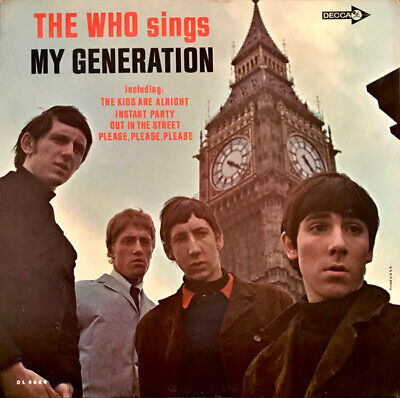

Recently I came across a copy of the US edition of The Who Sings My Generation in a three-dollar bin. Why was it just three dollars? It’s in stereo, not mono; the cover is very worn, and in fact the top of the cardboard sleeve is partially split; and an illegible name is scrawled in magic marker near the top of the back cover. Why did I buy it? Although I’ve had the tracks on the record since I was in high school in the late 1970s, and I have expanded CD editions of the record, I never have had a copy with the original US cover. My late-‘70s vinyl copy was as part of the double LP reissue that combined My Generation with Magic Bus. Yes, the same one that’s seen in the background in the party scene in the Quadrophenia movie. Despite its general excellence, that film, or at least that scene, was justly criticized for showing that record in a movie set in around 1965, though the double LP didn’t come out until 1973.

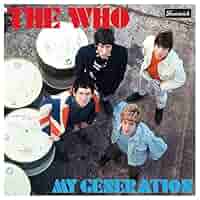

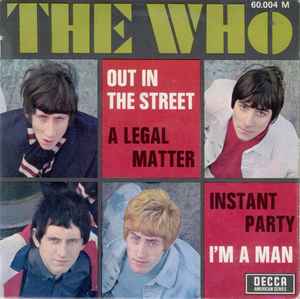

Although its music is by now super-familiar, there are reasons to own the original US cover, and not just to put on top of a shelf as sort of ambient artwork. The cover photo, of the moody Who with Big Ben hovering in the background, is entirely different than the UK edition, which used an overhead shot of the Who in colorful mod gear (and had the same tracks as the US version, except for substituting “I’m a Man” for “Instant Party” aka “Circles”). I’m guessing the Who didn’t choose the US cover photo, and many feel that US releases of the time in general bastardized the intended artwork of UK acts. I actually prefer the US cover photo, however, even if, I’m guessing, Decca Records chose it to emphasize that the band were from England. For what it’s worth, the vinyl itself on the copy I found plays surprisingly well, with no skips, and not too much surface noise, though there are some ticks.

The unsigned liner notes on the back cover are garnished with a bit of hype, and misspell the singer’s name as Roger “Daltry.” Actually, they’re fairly accurate, except for the claim that “following an extended engagement at the Marquee, the Who embarked on a fantastically successful tour with the Beatles.” They never toured with the Beatles, although they were one of the Beatles’ opening acts (in their High Numbers days) at a couple August 16, 1964 shows in Blackpool, and were one of many acts on a bill with the Beatles at the New Music Express Pollwinners concert on May 1, 1966.

There was a bit of image-building in the assertion that the Who are “often described as four tough, modern guys. They all hail from Shepherd’s Bush, West London [actually Keith Moon was from a different part of London], which is an area where most boys would sooner join a street gang than play in a group.” On stage Daltrey, it was noted, was “generally imitating whatever dances the audience may be doing on that particular night”; Moon “invariably winds up each performance with a bunch of broken drumsticks”; and Pete Townshend “has smashed fourteen guitars.” For those youngsters that did find this LP when the group were barely known in the US, the liners probably did the job of whetting their appetite, whether or not they’d managed to hear any Who singles on the radio.

Note, by the way, that the very title of the record was slightly different in the US and UK. The UK edition was simply titled My Generation, after the hit single title track. The US changed it to The Who Sings My Generation. I read at least once someone writing that the title was inappropriate considering singing wasn’t what the Who were most known for then, perhaps implying they also didn’t sing so well, or not so much sing as put vocals in a record dominated by instrumental mayhem. If so, that’s ridiculous. Roger Daltrey might not have been Roy Orbison, but he did sing effectively for the Who, and their harmonies might not have been as slick as the Hollies’, but they worked well for what they were doing. If Decca’s hope was to make the Who seem a little more palatable to US audiences by putting “Sings” in the title, it didn’t yield commercial results. The LP didn’t make the charts in the US, though it made #5 in the UK.

Decca Records has been criticized for poorly marketing the Who in the mid-1960s, one example being the graphic near the bottom of the back cover, which advises, “If you’ve enjoyed this recording…you’re sure to like these other great Decca albums…” The four shown are by Rick Nelson, the Kingston Trio, Len Barry, and Brenda Lee, none of whose music was similar to the Who’s in 1965, though all had done some records of merit, some of which the Who must have heard. It wasn’t an appropriate selection, but such back cover in-house ads weren’t uncommon at the time. The back cover of Bob Dylan’s rare 1967 Benelux single “If You Gotta Go, Go Now,” for instance, advertised nine singles by other CBS artists, including the Ray Conniff Singers, an easy listening act that couldn’t have been more unlike Dylan than almost anyone on CBS.

The actual music on the LP has been written about a lot, and properly praised. It could, however, have been a lot different, and appreciably worse. Unusually, most of the details were laid out back in July 1965 in the British magazine Beat Instrumental, about five months before the Who’s actual debut album came out.

John Emery’s story reported the album “has been completed,” producer Shel Talmy playing him an acetate with nine tracks. Nine tracks wouldn’t have been enough for an album; presumably, it was the basis of an album that might have come out, with two to four additional songs. What’s more, the story only detailed eight specific songs, making one wonder whether someone’s math was off. If not, what was the missing ninth track?

Anyway, these are eight tracks that were on the acetate. Although the exact sequence isn’t known, maybe it was in the order the story discussed them:

I’m a Man (included on the official UK version of the album; originally by Bo Diddley)

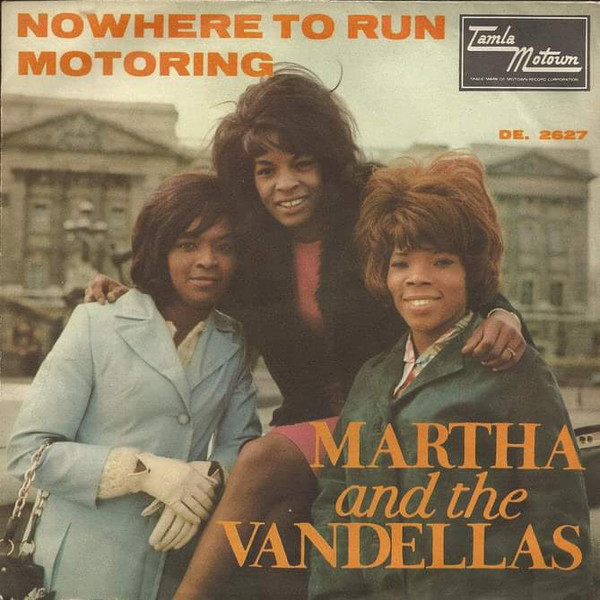

Heat Wave (not released until 1987 on the archival compilation Two’s Missing; not the same as the remake on the UK version of the Who’s second album, A Quick One; originally by Martha & the Vandellas)

I Don’t Mind (included on both the official US and UK versions of the album; originally by James Brown)

Lubie (not released until 1985, under the title Lubie (Come Back Home), on the archival compilation Who’s Missing ; originally by Paul Revere & the Raiders, under the title Louie, Go Home)

You’re Going to Know Me (retitled Out in Street, included on both the official US and UK versions of the album; the sole original song on the acetate, written by Pete Townshend)

Please, Please, Please (included on both the official US and UK versions of the album; originally by James Brown)

Leaving Here (not released until 1985 on Who’s Missing ; originally by Eddie Holland)

Motoring (not released until 1987 on Two’s Missing; originally by Martha & the Vandellas)

Even the Beat Instrumental reporter was hit “slap in the face just looking at the titles [by] the lack of originality in choice of material.” Not necessarily the songs chosen, I’d think, but the presence of just one Pete Townshend composition. That’s all the more odd since the Who had already made their UK reputation with a couple originals on hit 1965 singles, “I Can’t Explain” and “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,” the latter co-credited to Townshend and Daltrey.

One would guess the record would have been filled out by, if possible, more Townshend originals. Or, if there was haste to get an album out quickly, more R&B/rock/soul covers. They’d already used one such number, “Daddy Rolling Stone,” on the flipside of the UK 45 “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” Often groups tried to avoid using previously issued singles as album tracks, in which case they could have put on the Garnet Mimms cover “Anytime You Want Me,” which was mysteriously used as the US B-side of “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,” and hadn’t been issued in the UK.

They could have also put on “Shout and Shimmy,” the James Brown cover that ended up on the B-side of the UK “My Generation” single. That’s not to be confused with the much more famous Isley Brothers song “Shout,” though they’re pretty similar. Maybe they could have also revived “Baby Don’t You Do It,” the Marvin Gaye cover they’d already recorded at Pye Studios in late 1964 (as heard on the CD version of Odds and Sods); the song was clearly a group favorite, as they put a live version on the B-side of their 1972 single “Join Together.” The running order could have been topped off with an instrumental group jam a la “The Ox,” which wouldn’t have taken as much writing or arranging effort as a full-blown Townshend original.

Had all this happened, the Who’s first album would have been more akin to the Rolling Stones’ first album than The Who Sings My Generation. The Rolling Stones’ self-titled debut LP had, sort of like this acetate, just one fully developed original song, “Tell Me.” It wasn’t as characteristic of the early Stones as “Out in the Street” was of the early Who, but it was a good Mick Jagger-Keith Richards composition, and was a substantial US hit. But the rest of the first Stones album—which, like the Who’s first, was nearly identical in its US and UK editions, the US one replacing “Mona” with “Not Fade Away”—was entirely devoted to covers of American soul/blues/R&B/rock, with the exception of a couple songs that sounded like they were written in the studio. One was the basic, nondescript instrumental “Now I’ve Got a Witness”; the other was the Jimmy Reed-like “Little By Little.”

A sober difference between the early Stones and Who, however, is that the Stones were much better at covering R&B/soul/blues songs. So the first Rolling Stones album is very good overall; a good representation of the best of what they had to offer at that very early point in their career; and much better than a comparable Who album would have been. I like some of the Who’s early covers, especially “Daddy Rolling Stone,” though they did it better live on TV than they did in the studio. But the four songs from the acetate that didn’t surface until archival compilations—“Heat Wave,” “Motoring” (which was the B-side to Martha & the Vandellas’ hit “Nowhere to Run”), “Leaving Here,” and “Lubie”—are rather pedestrian, though “Leaving Here” is the best of that batch.

It’s odd, incidentally, that “Lubie”—sort of a novelty sequel to the infinitely more famous and better “Louie, Louie”—found anything of an audience in the UK. It’s not known how the Who became aware of Paul Revere & the Raiders’ version, actually titled “Louie, Go Home” when they put it on a non-hit 1964 single. But the Who weren’t the first British act to record it, as David Bowie—then known as Davie Jones—put it on the B-side of his first single in 1964, as leader of the King Bees. His version—using the title “Louie, Louie Go Home”—wasn’t very good either. Why the Who mangled the lyric into “Lubie” isn’t apparent. Maybe they simply misheard a record being played that wasn’t in their collections?

The James Brown covers and “I’m a Man” were better, though the lumbering feedback-strewn arrangement of “I’m a Man” isn’t nearly as good as the scorching hit version of the same tune by the Yardbirds. But although those three songs did get onto the album (only in the UK in “I’m a Man”’s case), in this acetate’s context, “Out in the Street”—or “You’re Going to Know Me,” as it was then known—clearly sticks out as the most exciting and original track by far. And the one that clearly displays the Who’s greatest assets, including Townshend’s feedback and distortion, and Daltrey’s aggressive mod posturing.

Displaying sensible judgement that was uncommon at a time when record labels were often rushing to put out whatever they could to capitalize on hit singles, the Who regrouped, canceled the supposedly completed or near-completed LP, and redid most of it from scratch. Presumably at least part of the main purpose was to allow more time for Townshend to write original material that would be more distinctive than the R&B covers filling out the acetate. As co-manager Kit Lambert told Melody Maker in its July 17 issue, “The Who are having serious doubts about the state of R&B. Now the LP material will consist of hard pop. They’ve finished with ’Smokestack Lightnin’.” The “hard pop” term might, incidentally, be the germ of the origin of the phrase eventually popularized as “power pop,” a genre of which the Who are usually acknowledged as the principal father.

The record that appeared in December 1965 would be mostly different, and mostly Townshend compositions:

Out in the Street

I Don’t Mind

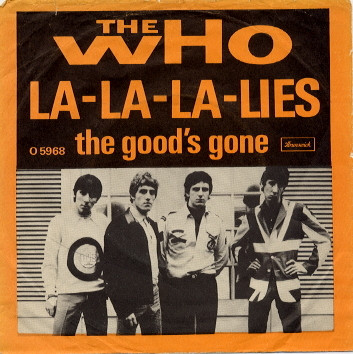

The Good’s Gone

La La La Lies

Much Too Much

My Generation

The Kids Are Alright

Please, Please, Please

It’s Not True

I’m a Man (UK edition only)

The Ox

A Legal Matter

Instant Party aka Circles (US edition only)

They did put on a single after all with the title cut. As far as the nine originals go, there’s not a dud in the bunch. “The Kids Are Alright” could well have been a hit single, and aside from “My Generation” is probably their most famous 1965 track. “A Legal Matter” was good enough to make it onto the first proper Who best-of, Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy. “Out in the Street,” “The Good’s Gone,” “Much Too Much,” “La La Lies,” “It’s Not True,” and “Circles” (mysteriously titled “Instant Party,” and redone in an inferior lower-energy version for a UK-only 1966 EP) might not be too well known outside the circle of Who fans, but they’re all good, tuneful, and bursting with vigor. Even the minimalist instrumental “The Ox” has its place for its sheer outrageousness, at least by 1965 measures, in its all-out fury.

So after the rehauling that had resulted in a much better LP than the one that apparently almost came out in mid-1965, was Pete Townshend happy? He never seemed entirely happy with the Who’s results, and even this early in the band’s lifespan, The Who Sings My Generation was not an exception. In the December 4, 1965 Record Mirror, he gave a very detailed track-by-track rundown of the LP—about as detailed as any such exercise of the time. These are worth repeating here and analyzing, especially as the column of sorts hasn’t often been reprinted:

On “Out in the Street”: “This was gonna be a single. I hate that ‘no, no, no’ bit. It was originally ‘show me, show me’ but Kit Lambert thought it wasn’t very good. He wrote all the new lyrics. I’m not gonna take the blame for any of them. It sounds all cut about and edited.”

Interesting that this was apparently considered as a single, presumably their third one (not counting the High Numbers “I’m the Face” 45 in 1964), to follow up “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” It did end up as the B-side to the US 45 of “My Generation.” Did Lambert write a bunch of new lyrics—in which case it seems like he might have been entitled to a co-composing credit—or just change “show me, show me” to “no, no, no”? I think “no, no, no” (which I always heard as “know, know, know”—maybe the reporter got this wrong) does sound better.

On “I Don’t Mind”: “This was gonna be on our first LP which never came out. It’s just a straight copy, well the best we could do of a James Brown number. It sounds better the way we do it now.” That seems to confirm they kept doing it live for a while, through the end of 1965, though no other version survives for comparison.

On “The Good’s Gone”: “One of mine. I like it. Roger sounds as though he’s about six feet tall when he’s singing. It’s a big bore this.” A direct contradiction between “I like it” and “It’s a big bore,” but Townshend often hasn’t been consistent in his evaluations, sometimes within the same interview. It’s unstated that Daltrey is considerably less than six feet tall, though his shorter stature is implied.

On “La La La Lies”: “It wasn’t as good as this before I did it with Keith. It’s not my favorite one on the LP. It reminds me a bit of Sandie Shaw.” Shaw never had a big hit in the US, but was very big in the UK in the mid-1960s with singles like “Girl Don’t Come,” which did get to #42 in the US. Townshend still had the Shaw comparison in mind when he put his 1965 demo on his Another Scoop compilation in 1987, writing in the liner notes, “Sandie Shaw had several hits, written by Chris Andrews, with songs that employed this rhythm.”

On “Much Too Much”: “I like the beginning of this. Sounds like Barry McGuire, doesn’t it? [McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” had just been a huge hit.] Very sort of folky. ‘Green Green.’” McGuire’s voice was gravelly, and Daltrey’s is gravelly on some of “Much Too Much.” “Green Green” was a hit McGuire sang lead on with the New Christy Minstrels. But “Much Too Much” does not sound folky.

On “My Generation”: “Rubbish! Any record that can’t get to number one is rubbish. If it gets to number one, it proves I’m wrong.” The “My Generation” single had entered the British Top Twenty a few weeks before this was published, and would peak at #2. This seems like an awkward attempt at humor by Townshend, poking fun at how a record’s status might be considered greater if it managed to top the charts.

“The Kids Are Alright”: “This was gonna be the B-side of ‘Generation.’ It’s our French EP. Shel Talmy said he’d prefer it as the ‘A’ side in the States. He doesn’t like taking chances, he doesn’t like doing anything. I don’t know where I got the idea for this one from, it sounds sort of symphonic. This is the favorite number on the LP of John, Keith, and me.”

Interesting that Talmy, probably correctly, sensed hit potential in “The Kids Are Alright.” Townshend later slagged Talmy on several occasions, and Talmy and the Who would engage in a lengthy legal fight by early 1966 when the Who and their managers didn’t want him to produce the group anymore. This indicates some resentment might have been growing before that. Note that Daltrey is the only member not named as considering the song his favorite. Did he not like it as much as the others?

“Please Please Please”: “This is another one of the old LP, same old crap. We didn’t want all this stuff on it. I’m a bit gone on all these electronic toys, these robots we’ve got. I don’t like all this rhythm and blues. I don’t play like that anymore.” Townshend seems to be referring to some distorted guitar effects in the break, where there are series of rapid wobbly notes. It’s fair to say he doesn’t seem too fond of the track.

“It’s Not True”: “This is everyone else’s favorite track. I hate it. Yes, I’m thinking of giving this one to a country and western group actually. They’re called the New Faces.” I originally wrote in this post, “More awkward attempts at humor, I think. It seems Townshend didn’t take everything in this summary seriously. The New Faces seems like a lame reference to the Small Faces, then the second-hottest mod rock band in the UK, behind the Who.”

But in the comments section, reader Scott Charbonneau notes there was an actual UK group called the New Faces who had four British singles in 1965-69 with a lightweight folk-pop sound, like the Seekers without the guts. So Townshend might indeed have wanted the New Faces to do “It’s Not True,” maybe in a country style. It does seem like the New Faces could not possibly have been confused with the Small Faces.

“I’m a Man”: “We recorded this years ago [probably meaning in the earlier batch that was on the acetate – not years ago, probably early-to-mid-1965]. I hate this as well. I don’t actually like the LP. It strikes me as kind of weird the way there are so many numbers from different stages of our career. I only hope they don’t expect us to do it on stage. It’s great how I get that plane sound out of my guitar. This is probably our best recorded feedback.” He hates it, but likes the feedback—more contradictory remarks. He does seem frustrated that the album is split between more recent original material (the substantial majority) and the four tracks that were on the acetate.

“A Legal Matter”: “I’m singing on this one. Put that it’s a similar voice to Paul McCartney.” More joking around. This was Townshend’s first lead vocal, and it’s okay for the Who’s purposes, but it doesn’t sound like McCartney.

“The Ox”: “This is the lead track on the LP [an odd remark—it was the final track on the UK version, though it was third to last on side two of the US version], we all wrote it except Roger [who doesn’t sing on it as it’s an instrumental, and presumably doesn’t play an instrument on it]. It’s an American sound like something you get from the Wailers. I got out of this something I’ve always wanted to get out of a piece of music. I like that piano break. Actually it’s John getting a piano sound out of his guitar. Nicky Hopkins is on this, he used to be with Cyril Davies. This session went on much longer and at the end we were all falling about.”

It’s interesting Townshend was aware of the Wailers, the Northwest band who did basic R&B/rock, and were not the same as Bob Marley’s reggae Wailers, who were barely known outside of Jamaica then. As the Wailers’ only Top Forty hit was the instrumental “Tall Cool One”—and not a huge hit—and “The Ox” was an instrumental, I’m guessing “Tall Cool One” is the record Townshend knew, and that he wasn’t aware of their numerous subsequent ones, which were often vocal with a frat rock/garage rock feel. But “Tall Cool One” isn’t nearly as fast and frenetic as “The Ox.”

So there’s a lot to say about The Who Sing My Generation. A lot more, in fact, than Decca wrote in the liner notes on the back cover of the US edition, even though those liner notes were pretty long for US releases of British rock bands that hadn’t yet become known in the US. Who would have predicted there would be so much to say so many years later when Decca put out the LP?