Sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Long before the phrase became a cliché, the Fugs combined those elements with political activism, satire, poetry, and other ingredients in a band like no other that operated in the last half of the 1960s. Big in the emerging rock underground, they never became stars, but broke new and often controversial ground in rock lyrics and rock theatrics during their half decade or so.

Like some other crucial artists, such as their Lower East Side New York peers the Velvet Underground, the Fugs are eminently worthy of a documentary, but handicapped by the shortage of prime vintage footage of the group. That’s a factor in Chuck Smith’s new Fugs Film!, but to its credit, it unearthed more such material than anyone knew was out there. More importantly, it benefits from recent first-hand interviews with the two surviving members of the Fugs’ core trio, Ed Sanders and Ken Weaver. The third, Tuli Kupferberg, is represented by some archive clips. A few of the other Fugs who drifted in and out of their numerous lineups were also interviewed (Peter Stampfel, bassist John Anderson, and guitarist Danny Kortchmar), as well as some people who knew the Fugs well, like Betsy Klein, Weaver’s girlfriend in the 1960s (who did the female vocal on “Morning Morning”), and arranger Warren Smith.

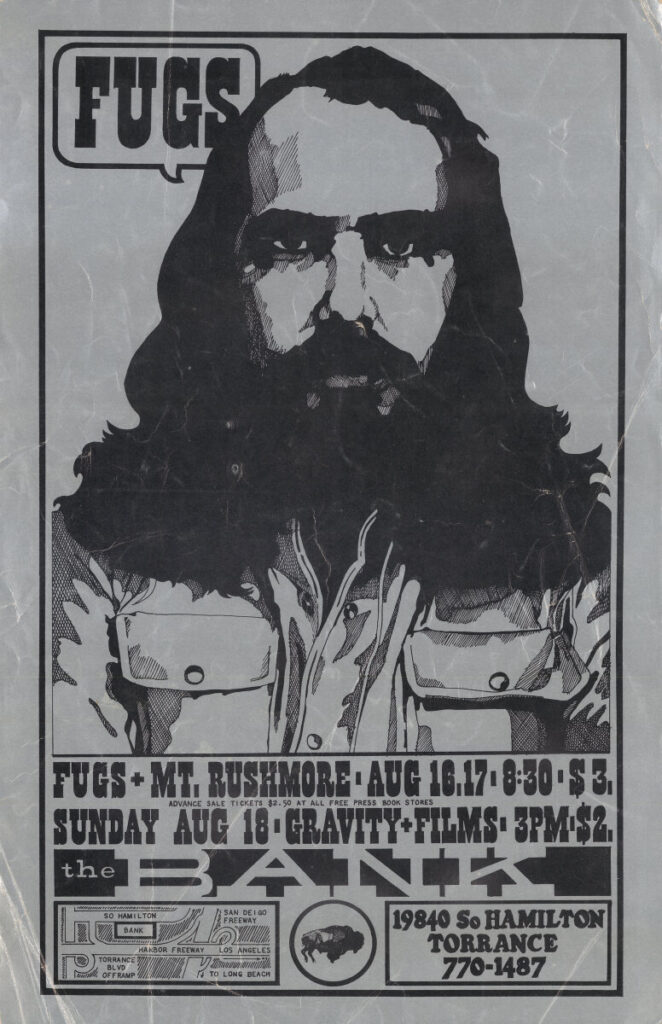

Although this isn’t a totally comprehensive history of the group, it does cover most of the main bases, including highlights from their records; their funny and oft-controversial performances, mixing bawdy humor with penetrating social satire; their participation in the effort to levitate the Pentagon in a 1967 protest against US involvement in the Vietnam War; their activities as poets and Sanders’s New York Peace Eye Bookstore; Harry Smith’s production of their debut album; and their breakup in the late 1960s when Sanders got tired of the effort involved in running a rock band. There are some genuinely good, high-quality performance clips filmed in 1968 in Sweden. Quips from a late-‘60s David Susskind interview with the three principal Fugs are also worthy.

But the biggest surprises are in the interviews. Weaver remembers watching his stepfather beat his mother to death as a youngster. Anderson, now living as a woman named Jackie, recalls getting a frosty reception from the Fugs after he returned from serving in the military in Vietnam, realizing he couldn’t rejoin the group, although he’d tried to get disqualified from service.

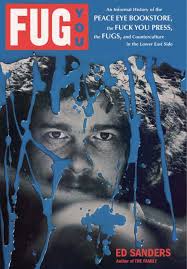

There are some interesting aspects of the Fugs’ career that aren’t covered in as much depth, including their interesting and sometimes fractious relations with record labels, and only passing or no mentions of some interesting members, like guitarist Jon Kalb (brother of the much more famous Danny Kalb), bassist Charlie Larkey (later husband of and collaborator with Carole King), guitarist Ken Pine, guitarist Vinny Leary, and keyboardist Lee Crabtree (as well as producer Richard Alderson). Some of this is detailed in Sanders’s autobiography Fug You, for those who want more info.

Chuck Smith is quite familiar with the Lower East Side milieu in which the Fugs emerged. He directed the 2018 documentary Barbara Rubin and the Exploding NY Underground, based around underground filmmaker Rubin, who in the mid-1960s was an associate (if sometimes fleeting) of the Velvet Underground, avant-garde filmmaker/critic Jonas Mekas, Andy Warhol, Bob Dylan, and the Fugs, among others. I spoke to Smith in November 2026, shortly after the premiere of Fugs Film! at the DOC NYC festival.

How did you decide to do the Fugs film?

To be honest, Ed [Sanders] asked me to do it. He was a friend of Barbara’s [Rubin’s], and he had seen the film and he loved Jonas Mekas. And he trusted Jonas, and he knew that Jonas trusted me. And so, after he saw that film, I think he’d been thinking of doing a Fugs film. Many other people had approached him over the years, but he’s very smart. Somehow he thought that I would do a good job.

I didn’t really want to spend more time in the ‘60s. Yes, I knew it well. But I was kind of hoping to get out of that for my next film. But it was just too good of an idea. I said, yeah. Also, I knew he was getting older, and Ken Weaver was still alive. So honestly it was ‘cause Ed asked me to do it, and said he would give me all the music for free, which I knew was a big issue. Because for the Barbara Rubin film, you need to get rights to music. He said he controlled most of it, and that’s a done deal. That’s how it started.

So Ed was the sparkplug.

Yeah, he was the sparkplug. He’d been going through his archive, because he was about to give his archives to Princeton. So the history has always been in his mind. Not that he doesn’t always think about history. He’s an amazing archivist, an historian. But he’d been preparing his archive to send to Princeton. The first day I filmed with Ed was just before that, because I kind of wanted to see the archive before it moved to Princeton. The week before they picked everything up, I was up there while he was going through the files. I looked at all the Fugs boxes, and started going down memory lane.

So it’s kind of a good first way to start filming with Ed. In fact, I think a little bit of that interview is in the film from that first day. Because it’s always exciting when you first start talking to someone about something. But right away I knew that Ed has written about this. He’s done an autobiography, he has stock answers to things. And I don’t really like stock answers. I like emotion and some feelings. A little bit like Jonas too…

Anyone who’s been around a long time has been telling stories for years. They say the same kind of things. I could sense right away that Ed was giving me the spiel. What I really wanted was to do it enough that I’d break him down. I finally did get there, both with Jonas and Ed at some point, and break through the stories that are told over and over.

It’s interesting there’s an archive of Ed’s material.

It’s at Princeton. But it was also an archive of the ‘60s. Not only did he collect all the Fugs stuff. He had every issue of Fuck You, his magazine. He had every issue of the [‘60s New York underground paper] East Village Other. He had tons of memorabilia, and all his research for Manson [for Sanders’s Charles Manson biography, The Family]. It was his entire archive, which was about three little cabins or sheds full of stuff. It was a giant truck. It was a big event. He had boxes and boxes of fan mail from then, and that was fun. It’s a cool way to start.

It must have been a big challenge to put together a full documentary with such little vintage film footage of the Fugs. It’s fortunate there’s the fifteen minutes or so of performance from 1968 in Sweden.

Yes. You always hope there’s going to be some great discovery. I’d already known about the Swedish thing, which was great. But that’s really later in their career, and that was one of the problems. Then of course, Ed English had done a film with them, twenty minutes, called The Fugs, which is also in the movie. Those are the two extensive documentations. That Fugs film was from 1966, so that was an earlier version [of the band]. So between that ’66 footage and the ’68 footage, I was like, I could do it. I kept thinking, I’m gonna find something new, something great. But I didn’t find any video. I did find some cool audio stuff.

They were on the BBC in ’67 twice, and I think someone must have shot their Roundhouse shows [at the renowned London venue The Roundhouse]. But I couldn’t find it. In the end, I was stuck with ’66 and ’68. The other interesting thing about that is, the camera wasn’t there during some of the big events, like with the Velvet Underground as well, that you want to document.

I really don’t like animation or had never used it, and didn’t like it in some films. But I knew I’d probably want to try some animation for this one to tell those stories. And I knew that Drew Christie had already animated the Holy Modal Rounders [documentary The Holy Modal Rounders…Bound to Love] and Harry Smith [the animated short Some Crazy Magic: Meeting Harry Smith]. I was like, okay, that’s a start. So I liked him, and then Lucy Munger, I loved her stuff; that’s the kind of animation I love, the cut-out stuff. So for levitating the Pentagon, I thought, she’s gonna be great.

You always do hope for this great footage that no one discovered, but I couldn’t find any. It’s amazing, because they did over 500 shows in New York City at the Players Theater, and nobody…no TV station [filmed them there]. As you know with the Velvets, the other problem is that the people who were running around with cameras were Barbara Rubin and the people who were avant-garde. So nobody was locking down and shooting a show the way they did in Sweden, or the way they did in Europe. Frankly, if the Velvets had gone to Europe in ’67 or ’68, someone might have shot them beautifully, like they did the Fugs. All the best Coltrane and jazz stuff, it’s all from Europe in the ‘60s.

So I had tons of really wacky footage. In fact, I did discover some psychedelic footage of them in San Francisco in ’67. But you can’t even see who’s playing. It’s just a bunch of lights and stuff. It was a crazy time for whatever the handheld cameras were. But there’s just enough.

I did find some actual footage that [renowned independent filmmaker] Shirley Clark and Barbara Rubin shot of them flying down to DC for the Pentagon protest and levitation. So that’s in the film. I can see Shirley Clark onstage with the Fugs with a big sixteen millimeter camera. I know that footage exists, and I think it’s in Ornette Coleman’s son’s, Denardo’s, garage. But I couldn’t get Denardo to get it together to give it to me. It’s almost easier when there’s not much footage (laughs).

The Fugs’ career had a lot of different aspects. There’s the music, the political activity, their literary activity, their lyrics. What did you want to focus on for the kind of story you wanted to tell, in a little less than 90 minutes?

The good news is, I wasn’t really a huge…growing up, I did like the Velvet Underground. I knew of the Fugs, but it wasn’t like I was a fanatic. I knew they did some interesting things, but I wasn’t enamored. So I was really coming to their catalog and what they did cold, which was great. You always want to make the film you want to watch. I just wanted to watch a good summary of all the cool things they had done.

And they are super-eclectic. From their first album to all the different…it’s almost operatic, some of their later songs are like opera. They do have people going “ahhh.” It was very diverse, but I knew it was all interesting in little bits. I really just wanted to let someone who knew nothing about the Fugs to uncover a huge strange band that came from these zines. They really did the first zines. That’s part of the film too; both Tuli and Ed had done very cool magazines. And that they were poets.

It wasn’t one particular thing, but how you condense it all. Every time I look at it, I think of all the stuff I left out. So much stuff, we left out. But you get the idea that the Fugs were interesting and innovative, and that’s all you need.

Another challenge is that in documenting what happened 55-60 years ago, a lot of the people aren’t around, or might not be around much longer. You got two of the three most important Fugs. You couldn’t get Tuli [who died in 2010 at the age of 86], obviously. That must have been a good head start in telling the story.

Yeah, absolutely. Ed has been around forever; I knew Ed was gonna know everything and be able to give stories. But I really feel very proud [of] the moments where he got emotional, which he hasn’t talked about much—his mother, or losing Tuli. So to get Ed to get a little emotional was key for me.

Then I didn’t know Ken’s story. Ken Weaver was a mystery. I knew that I wanted to talk to the Crumbs [cartoonist R. Crumb and his cartoonist wife Aline Kominsky-Crumb] when I was out there, ‘cause I knew they were good friends. When Ken starts talking about his childhood, I was like flabbergasted. I was like, oh my god, this is another level. These are things you don’t know going in, and Aline was a huge Fugs fan and told some great stories. Six months after we talked to Aline, she passed away, sadly, and she was so healthy and vital. It’s really important to get all these things.

The good news with Tuli was that he was very well documented, more than the other guys. Even though I didn’t do an interview with Tuli, there were interviews with him, and there was tapes of him. There was actually film footage from some of the movies he was in. So I felt like I got really lucky that the one Fug that I couldn’t talk to personally, there was a lot of documentation of.

You talked to some important other members and associates, like Peter Stampfel, John Anderson (now living as Jackie), and Betsy Klein. Was there some really valuable material from those interviews that you weren’t expecting?

Betsy Klein is a fascinating person. She knew Timothy Leary very well, and helped him get out of jail. She has stories, but she’s also incredibly private, and she lives hidden somewhere. It’s not even the name she’s going by now. So the fact that Betsy agreed to be in the film and to give me an interview…and I didn’t know if I was going to be able to use it after we interviewed her. She would have had to feel comfortable. And thank Betsy that she really did feel comfortable.

But she was another big mystery. People knew she sang on “Morning Morning” [a highlight of the Fugs’ second album, 1966’s The Fugs], but she was a huge part of the Fugs back then. And she was with Ken Weaver. Obviously she’d be an interesting person to talk to, but she was extremely private, and not the kind of person who would agree to everything. She didn’t even sign a release. I had to interview her first, and then got the release. Thank god she did like the way she turned out, and I kept it private enough, and we call her Betsy Klein, so that’s good. People wouldn’t be able to find her. So that was a blessing. And because of Aline Crump…that’s her best friend, was Betsy.

I wanted to find all these Fugs, and I didn’t know which ones I could find. I keep hearing Vinny Leary’s around, but I wasn’t able to find Vinny. I don’t know if he’s a great storyteller. But John Anderson just looked interesting, and I had footage of him in that ’66 thing. I could see he was a cute young guy, so I knew I wanted to find him. I didn’t know he changed his name, so I went to Yale [where Anderson had gone to college]. Then of course to discover that he’d become a woman was like, oh my god, this is really good. And then to discover that he was the one who went to Vietnam, it was like a double win.

Her story, Jackie’s story, really makes the film much deeper than it would have been. Because it brings home the Vietnam story. Also, she’s a great interview. I reintroduced her to Betsy, so Jackie and Betsy are best buddies again. They loved each other back then, too. So I love that story. Those are the things you can never imagine before you start.

Peter Stampfel must have been very accessible.

Peter’s an unfiltered, amazing resource. Steve Weber [who was in an early Fugs lineup with Stampfel, though Stampfel and Weber are more well known as longtime collaborators in the Holy Modal Rounders] would have been amazing. But thank god Paul [Lovelace, co-director of The Holy Modal Rounders…Bound to Lose] did the Holy Modal Rounder doc, and got Steve before he burned out. Really, the Fugs went on to be more than that. But at least getting Peter to talk about those early days was great, too. And kudos to Lenny Kaye and Jeffrey Lewis, who are both true fans, and Penny Arcade, who really know the subject well, and were able to talk very well about [the Fugs, when interviewed in the film].

Ken Weaver having watched his stepfather beat his mother to death, and John Anderson’s transition to a woman, must have been the biggest surprises.

I would say it’s not just a tragic incident for Ken Weaver, it’s his whole fucking childhood was a disaster. I couldn’t even begin to tell you all the shit he went through. We touch on a little bit. He’s written a memoir where he doesn’t even mention the Fugs. The memoir’s about the first eighteen years of his life, and it’s really good, dramatic, and crazy. Yes, definitely Jackie was a great story.

And learning about Ken’s motivation explains Ken very well, and makes him a sensitive character. Because he always looked like the toughest Fug, but he was also the sweetest in a way.

Jackie talked about her experience getting drafted and going to Vietnam, where she didn’t want to go. It’s poignant how when she came back, the main Fugs were kind of aloof and disapproving of her having served there. It seems like they could have been a little more understanding of his situation.

Yeah. I have to say, I don’t tell the whole story there. Because honestly, Tuli from the get-go would have preferred if [John, as he was known at the time] had gone to Canada. He would have helped him get to Canada. The Fugs, when [John] said I’m not a speed freak, they actually did load him up with tons of drugs and take him down to make him look crazy. So they helped him try to get out by becoming a crazy drug addict. It didn’t work.

So they were trying to help him get out of it, and to this day, I think Ed still has a hard time with anybody who goes in. I don’t know what Jackie did exactly in the war, but from Ed’s point of view, he called in some strikes on Vietnamese or whatever, that he was involved in bombing. He still says she didn’t have to do that.

You know, life is messy. Jackie did have family members who’d been in the military and she didn’t want to go, but she also knew that everybody else in her family had. You know, it’s tough. But if you’re really gonna be such an antiwar band and take stands, then yeah, it’s hard to come to grips with someone who actually went over there.

It’s kind of odd, in the Swedish footage, to see Tuli onstage with the band, but he’s not singing or playing anything, just dancing.

(laughs) Somebody watched it and said, I love Tuli, but what did he do in the band? First of all, he wrote a lot of great songs. So the fact that he’s even there is because he’s kind of like the Robert Hunter or whatever of the Dead. But he did play the [handmade percussion instrument] rectarine, and he did sing some of the stuff. Ed was a very different kind of singer, very perfectionist, he wanted everything to sound perfect. It bothered him that Tuli would get off-key a little bit. I wish he would have trusted Tuli a little more on that stuff. Because there’s an emotion when Tuli does stuff that really cuts through the bad notes. Certainly if you watch Bob Dylan enough, you’ll know that he doesn’t care about bad notes. And it comes through.

So Ed was a real perfectionist and sort of ran things, and I wish there was more footage of Tuli singing. But he didn’t really sing very often. If you went to see the Fugs, he would do two or three songs max. So that was tough.

Someone told me he saw the Fugs around 1967, and for the whole performance, Tuli just lay in a coffin and didn’t do anything else. I haven’t been able to verify that story. Did you ever hear that?

No, but it sounds like it absolutely could have happened. There’s no doubt that could have happened. I’m sure he didn’t sing at all on several shows. He was always into the theatrics of it. Really, the early shows were very theatrical. They were probably one of the first super-theatrical bands. Later of course everybody got theatrical. But what they were doing was theater as much as anything else. Tuli was a real part of that.

I saw Beck play once, and there’s a guy in front that was just a party motivator. He was just dancing. I was like, what is he doing? Well, he was keeping everybody excited, and taking the attention away from Beck, who preferred to be off to the side. I thought, that’s genius. So he had a party motivator center stage, and in a sense I think Tuli was a little bit of the sub-motivator, even though he doesn’t sing much.

Some of the footage of Tuli was from the [1971 underground ]movie W.R.: The Mysteries of the Organism, right? The color footage, especially.

Yeah, when he’s dressed up like a military, running around, the “Kill for Peace” stuff. Yeah, that’s great. Again, the fact that he was in these movies and there’s footage of him makes him become a part of the film more than he should have been. Because I didn’t find anything else.

You found some good interview footage, the David Susskind clips especially. Did you know about that before you did the film?

I kind of might have, because from the Barbara Rubin days, I was definitely looking at some old Susskind shows. ‘Cause he really had everybody on the show. The funniest thing is, it says “part 2” of the Fugs. And I’ve never known what’s in part 1. So that’s part 2 of the Fugs, the one that’s on tape, the one that Ed has a transcript from in his book. So I knew that existed. But it says part 2, and I’ve never been able to find part 1.

That kind of stuff really gives you a flavor of the time, when you get to see people in the audience asking questions. I just saw John and Yoko’s One to One film [a recent documentary about their early-‘70s activities]. One of my favorite things is that it just plays commercials from 1972, like Chef Boyardee. It puts you in that mood. You really remember what it’s like to be in 1972. I think one thing that Betsy said that she really likes about the [Fugs] film is that it really captured what it was really like to be back then. I’m happy she picked up on that, because I love the ‘60, and I want people to understand the ‘60s. With the Vietnam story and the free love and all that psychedelic drug stuff, that’s what it was about.

The Fugs’ lyrics have sometimes been criticized for being sexist, or obscenely explicit. Betsy Klein, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and Penny Arcade’s comments put a feminist perspective on them, seeing them as liberating in some ways. Penny Arcade, for instance, views their “Supergirl” as being empowering.

Penny Arcade, I knew I wanted her to play that role in the film. Because she wasn’t personally connected to the Fugs as Aline or Betsy [was]. Of course they’re gonna like the Fugs, ‘cause they were dated them, or they loved them. But Penny, I used her as an outsider. I’m glad she’s there for that purpose.

I asked Patti Smith if she wanted to be in the film, but Lenny [Kaye, longtime guitarist in the Patti Smith Group and rock historian] had already said he’d do it. She said, they weren’t too friendly to women, were they? I was like, well, you know, that’s debatable. She said, I’ll let Lenny do the talking. That’s fine.

I think the Barbara Rubin film showed how sexist the ‘60s were. They were in a way. But the whole society was breaking out of stuff. So I really think the Fugs, talking about women or sex, is just more like freedom of speech, and breaking all boundaries. Which included sex, very much.

There’s some other even more egregious stuff in the Fugs’ catalog which people can discover on their own. But you can’t judge a band by their least politically correct song. If you would, the Fugs would never be in the running at all.

The Fugs ran through a lot of musicians in five years in various lineups, besides the mainstays of Sanders, Kupferberg, and Weaver. In the Swedish footage, I’m not even sure who the drummer is, though I know it’s Ken Pine on guitar and Charlie Larkey on bass. Do you have any speculation as to why that was?

Jeffrey [Lewis] is very good on Wikipedia to list pretty much everyone. But that was Bob Mason on drums in Sweden. I think Kootch [Danny Kortchmar] sums it up the best because he was in the band for a while too, and Charlie Larkey. I talked to Charlie too, but it’s not in the film, because he’s a very quiet, private guy. But it was fun to talk to Charlie. But I think at one point [I asked Kootch] why did you leave the band. He said, well, I kind of wanted to play with real musicians who knew what they were doing.

Also, Ed knew right away that these are the three Fugs [Sanders, Kupferberg, and Weaver], and he knew that people would cycle through. Some of the very early days band members came and left. So they were not full band members. They were sort of hired guns from the get-go. Probably Ken Pine is the one Fug who I think they should have just welcomed into the band, he might have stayed longer. Ken came to the premiere the other night. I was so happy to meet him. He’s a genius guitar player. He used to play with Hendrix. He really was a great musician.

But it’s hard to be supporting the band every night and arranging stuff and playing a real part in the band, and not being treated like the three main Fugs. I understand why Ed did that, because it’s hard to lock in somebody who may not want to do this every night. But that’s probably why they went through a number of people. Because other opportunities came up. And for a musician, you might to move on. ‘Cause this was theater, a lot.

It’s interesting that Kortchmar and Larkey went on to the very top of the session world. Kortchmar as one of the top Los Angeles studio session guitarists, and Larkey as a collaborator with Carole King, to whom he was married for a while.

They sure did. When they were in the Fugs, they sounded tight. They were good. Ken [Weaver] will be the first to tell you he’s not a good drummer. That’s why, in that footage, there’s a second drummer, Bob Mason. And Kootch would play drums sometimes too. So I think it was frustrating for these really good musicians to be in the Fugs. At a certain point, their show became sort of fixed. It was like a touring show. There wasn’t so much new music, and they didn’t have time to do new music. I think that’s another factor of them wanting to play with bands that might jam, or do something fun.

Jonathan Kalb [brother of Blues Project guitarist Danny Kalb] came the other night too. Jackie remembers that summer of ’66, when Jonny Kalb and Jackie were in the band, Jackie was a very good musician, and a great bass player. So Jackie and Jonny were in this band, and Jackie said, there’s no recording of it, but that summer of ’66 she felt like they were a really good blues band. They were a really tight band. I wish I had recordings of that, but I haven’t heard any. But Kalb was only in the band for three months. So again, you’re hurting for not having good recordings of things.

Of course, the sound back then was horrible. I don’t know if you noticed, but almost none of the music is the actual sound from the live performances, or not all of it is. It’s synced up so it seems like it is, but it’s from better recordings. Live audio recordings sucked in ’67, ’66. There’s other docs on the Dead or the Beatles where really great footage had bad or no sound, but they found other performances that had great sound and that makes it great. So I did a little of that kind of—magic.

I have to give a shout-out to one other person who wasn’t around to talk to, Lee Crabtree. Lee Crabtree is an amazing, interesting story. He did help arrange a lot of the early songs. He was there at their transition from the Peter Stampfel style, the folky stuff, into the more musical. Lee Crabtree really helped a lot, and then he jumped off the Chelsea Hotel and killed himself [in 1973]. He was friends with Patti Smith. But he was a troubled person. But he’s in the background there in the film, and he came up here and there. And he’s on the albums. He was a great musician, and a very interesting person.

Besides their first album on Folkways and Harry Smith producing that, there’s not much about their involvement with record labels. Did Ed Sanders not want to get into that, especially ESP, who put out their second and most popular album (The Fugs, 1966) and then put out an album of outtakes (Virgin Fugs) without their permission?

No, it gets into inside baseball. But you’re right, he hates ESP like everybody else does. He did buy his catalog back from ESP at one point. He was particularly pissed off about Virgin Fugs. Because for the year of ’67, the summer of love, Ed was always upset that the Fugs had nothing to release. They had recorded all the songs [for an album on Atlantic Records], and they could have put ‘em out. But there was no label, no deal. I guess Atlantic dropped them, they declined to pick it up.

So during that summer, ESP released Virgin Fugs, and Ed was so pissed, because he didn’t even know they were gonna do that. There’s a song on there, [based on the opening line of Allen Ginsberg’s poem] Howl, “I Saw the Best Minds of Mine Rot,” that Allen didn’t like. Ed had promised it wouldn’t come out, and then it did come out. Ed loved Allen, he didn’t want to upset him. He apologized, he knew why it happened. But he was very upset with ESP.

The Reprise years, I think [when they were on Warner Brothers subsidiary Reprise in the late 1960s], they were very happy to be able to do what they wanted. But there was that key year where they really didn’t release anything, which was kind of tragic. Except Virgin Fugs came out.

When Steppenwolf mention the Fugs on a clip from the Ed Sullivan Show and Sullivan himself actually says the name, did that actually get on the broadcast?

Yes.

Did you know about that before doing the film?

No, not at all. And shout-out to [filmmaker] Jacob Burkchardt, Rudy Burckhardt’s son. Jacob knew about it. He said, have you heard that? ‘Cause it was very funny to him. His father, genius filmmaker, has amazing archives. Also, in terms of the archival footage, I have to give a big shout-out to Jonas Mekas, his archive, amazing. My friend Ken Brown, who had done the light shows at the Boston Tea Party in the ‘60s, his light show footage is in there.

I really feel blessed that I know these people who have these amazing ‘60s archives, which gives the feeling. And to be able to use Rudy Burkhardt’s footage, to tell stories in the ‘60s, is amazing. Same with Jonas, and same with Ken Brown, and Ken Jacobs. I mean, all the geniuses of ‘60s filmmaking. So if I have any great thanks, it’s that I already knew all these people from the Barbara Rubin film, and being able to use their archives for fairly good deal, because they’re friends, is great. Because it’s amazing stuff.

Ed talks about how the Fugs broke up at the end of the 1960s as he didn’t want to keep running the band any longer. What do you think the Fugs might have done had they stayed together longer?

I don’t know. I really think it’s sort of a perfect example of a band that only lasted as long as it could have. We don’t get into it so much, but Ken will tell you again, he was a huge drinker, and not a very good band member. He wouldn’t show up sometimes. Him and Janis Joplin and Pigpen would drink entire bottles of bourbon sometimes together. So he was not a healthy person then, Ken. It almost became like, get up there and do your thing, Ken, and he was drunk, and he would just do it.

So there was some serious issues. I think Ed got very political and was so busy that he even said – it’s not in the film, but in one of our interviews – I wanted to take the time to write a really antiwar song, or I wanted to write more songs. But I didn’t have the time. And Tuli needed someone like Ed to keep him going on things like that. He wrote some amazing songs. But I think in a way they lasted exactly as long as they should have, and could have. Separately, they might have been able to do more. And they did.

But they were never only musicians. That’s the key thing, that they really were more than that. When I talk to [Ed], he’s always moving on, he’s like, I just gotta write one more book, I’m gonna write another book. He’s always got stuff going on. So shout-out to Ed for being committed to getting the work done, and all these years. He’s a creative force.

How do you see the legacy of the Fugs now, long after they broke up?

I think any band that’s out there doing wild stuff. When I wear my Fugs shirts now, people say, oh, the Fugs! Some guy in a band said, we do a cover of “I Couldn’t Get High,” and everyone thinks it’s our song. And I tell ‘em, no, it’s the Fugs. They’re a perfect discovery for people who – people love discovering unknown things, and their archive is vast. Also, they’re TikTok ready. “Boobs a Lot” is a TikTok-ready song.

In little clips, they’re amazing. So in some sense, I really hope people rediscover the catalog. I keep telling Ed, you’ve got to manage your legacy better musically, because it was a little bit left unmanaged. And still is, kind of. He’s in control of things, but I do see in the future someone organizing it better and hopefully it being presented well. Like the Velvets has gotten—a reassessment and a look at it. I really think if they’re edited and curated well, the Fugs have amazing gems, as you can find in the film. There’s more that I didn’t put in. I hope to put out a playlist, or at least maybe get a Light in the Attic to put out a soundtrack album, or something.

It is the kind of music that I think still sounds fresh, and it sounds like a discovery. ‘Cause nobody quite sounds like the Fugs, let’s be honest.

Are there plans for a home video release that might have more footage?

I’ve definitely got a lot of that stuff. I’m thinking about it. Certainly Aline Crumb’s story of getting dope backstage didn’t make it in the film, but that’s a great story. There’s more gems in there. I’m a very tight editor, and I cut things out all the time. I’ve still got stuff from the Barbara Rubin film that I should release.

Was the Doc NYC screening the first one?

Yes. Two showings, it sold out. We have one more screening December 1, at Upstate Films, Saugerties [New York State]. We’re gonna do a sneak peek, and that’ll be on Zoom, and I’ll be there. There’ll be no more showings until 2026. Then we hope to do some more festivals, maybe get out to the west coast, and then find a streamer or some way to release it online.

You’ve gotten good reactions so far?

Yeah. I’m not trying to brag, but people have liked it a lot. What I really like is young people have liked it. I was going to one of the Doc NYC events the other day, and like a 25-year-old who was checking tickets at the door said hey, thank you so much for making that movie, that was the best thing I saw. Then this woman from Brazil said, oh man, that’s film’s amazing, the aesthetic is so cool. But the ‘60s are always cool, I think, for younger people. I really hope young people discover the Fugs. Certainly the old radicals are loving it, but so do the younger people, which has really made me feel good. These are deep dives into stories, and the Fugs are a rich one.

What are you doing next?

I have two projects that are hot to trot. One is a David Cassidy/Partridge Family musical, actual theater, that I’m working on, which I’m really excited about. I think their catalog has been woefully ignored. Just before the Fugs, I wanted to do Bobbie Gentry, who’s amazing. Even if you don’t get to talk to her, keeping the mystery is amazing. She has not talked to anybody. Apparently she kept all her own publishing, and she wrote all those songs. She’s genius. I love mysteries like that, and I would love someone to do it if I can’t do it. But boy, it’s a good story. And the songs sound good.