If not quite as great in number as rock reissues and books of interest to me (with lists to come in the next few days), the number and range of music documentaries continued to be impressive in 2025. It’s not surprising to find docs on superstars like Led Zeppelin and Billy Joel, but more so when cult artists with little surviving performance footage get their turn, like the Fugs. And documentaries on events, festivals, radio stations, record labels, and TV programs show you don’t have to stick to musicians to make a good film about music.

As usual, some of these films might technically have premiered somewhere before 2025. A few have barely been shown, although I was fortunate enough to have been able to see them. They all fall in the 2025 bracket, however, as far as gaining their first wide distribution and/or official premieres.

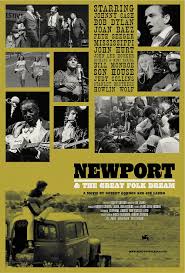

1. Newport & The Great Folk Dream. For every year between 1963 and 1966, parts of the Newport Folk Festival were filmed, forming the basis of Murray Lerner’s documentary Festival!. Many more hours of footage were taken than were used in that movie, and those in turn form the basis of this new documentary about the festival during 1963-66. While there’s some footage that’s also found in Festival!, most famously Bob Dylan’s electric rock performance of “Maggie’s Farm” in 1965, there’s a lot that isn’t, from famous performers like Johnny Cash and John Lee Hooker through to non-professional pure folk acts that didn’t make records. There’s also some interview footage from those years with performers and audience members at the festival, though the emphasis is wisely on numerous excerpts from performances. Also wisely, while there’s interview material specifically recorded for the film with the likes of Judy Collins and one of the audience members seen in the movie, these are presented in voiceovers rather than as talking heads, allowing the images to complement the memories with fuller power.

Highlights are so numerous they’re difficult to fit into one paragraph, but these include clips of the Chambers Brothers doing electric folk-blues-gospel in 1965; the Paul Butterfield Blues Band performance, with Mike Bloomfield on incendiary guitar, that sparked a fight between manager Albert Grossman and folklorist Alan Lomax over Lomax’s condescending introduction; Howlin’ Wolf in 1966, taking his mike into an audience and gyrating in the middle of a song; the Lovin’ Spoonful performing electric folk-rock in 1966 (it’s sometimes not remembered that electric music became a more accepted part of the festival after Dylan’s controversial 1965 appearance); and Richard & Mimi Fariña merrily playing in a rainstorm in 1965. Yet some of the more purely folkloric snippets are amazing too, like an a cappella group from Cape Breton singing with tablecloth wipes as percussion, or a spiritual group chopping wood as part of their show (one of them losing a grip and dropping his axe in the midst of it). As for the voiceovers, Loudon Wainwright III has a memorable soundbite about Dylan messing with the folk that was expected in 1965, using a much stronger verb than “mess.”

As always with survey documentaries, as good as the vintage footage is, it raises hunger for seeing more that exists, especially since about 80 hours from 1963-66 survives. Perhaps some can be made available as home video extras or on separate releases, as was done with some of the performances Lerner filmed at the 1970 Isle of Wight festival.

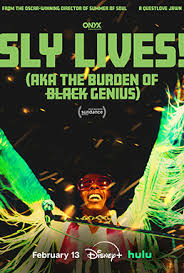

2. Sly Lives! (aka The Burden of Black Genius) (Hulu). Sly Stone isn’t the easiest of subjects for a documentary, as the still-surviving legend isn’t easy to access for interviews. He wasn’t specifically interviewed for this nearly two-hour film, but there are a lot of archive clips and, more importantly, quite a few interviews done for the film with close associates. Those include the Family Stone (though his brother Freddie and sister Rose are barely represented by these), several of his children, George Clinton, and some post-1970s stars discussing his influence, with the latter category not overdone, as it is in quite a few such productions. There are also quite a few vintage clips of Sly in performance (usually with the Family Stone during their prime), a wealth of photos (some rarely seen, at least by me), and some context about the times in which he functioned (again, not overdone), including the period’s racial relations.

Refreshingly, the music itself is not neglected, with stories of how hard the band worked (at least in its first few years), the significance of their unison harmonies, and how Stone was among the first musicians to creatively work with drum machines. Although “Dance to the Music” is depicted as a wish for a simple song that could be a hit (which it was, of course), it’s justly praised and detailed as their commercial breakthrough. Sly himself is justly praised as a musician and bandleader, but his lesser qualities aren’t overlooked, including his growing and excessive drug use; freezing out other band members from the creative process in the early 1970s despite their initial family-like closeness, helping lead to the split of the original and best lineup; his growing unreliability at showing up on time or at all for concerts; and his rapid artistic post-Fresh decline, which by the 1980s included a long prison record. The decline isn’t unnecessarily dwelled upon, the emphasis being on his artistry and triumphs. Because his and the Family Stone’s story is so complex that it can’t be wholly covered even in a fairly lengthy documentary, it does make you wish for a comprehensive written biography. None has yet appeared, though Joel Selvin’s oral history has worthwhile information, as does Stone’s rather fragmentary memoir.

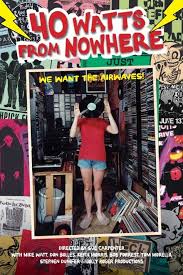

3. 40 Watts from Nowhere. In 2004, Sue Carpenter’s engaging memoir of running a couple pirate radio stations in the mid-to-late-1990s was published. About twenty years later, she’s directed a documentary based on those experiences. While it naturally covers a lot of the same ground as her book did, it’s not simply a retelling of that narrative. It draws on a lot of footage taken at the time for an unrealized documentary on the Los Angeles pirate station KBLT that was run out of her apartment. That includes many of the DJs and others affiliated with the operation, as well as some performances artists did for or at the station. Some pretty well known musicians appear in those guises, if fleetingly, including Mazzy Star, Mike Watt, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. More interesting, however, are the numerous interviews done with station personnel at the time and, crucially, quite a few done specifically for this new documentary. Carpenter herself is extensively interviewed both in the vintage footage and the material shot for her own film.

Carpenter had briefly overseen a pirate station in the mid-1990s in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles to more or less helm the much more well known KBLT for a while in the late 1990s before it was shut down by the FCC. KBLT specialized in broadcasting alternative music of all kinds, if primarily alternative rock, judging from the film. The memories of doing the groundwork for getting on the air, as well as the fun and sometimes rocky times putting music on it to considerable enthusiasm from adventurous locals, are entertaining on their own. An important message that also comes through, however, is how the station helped build a community of people determined to provide something different from what mainstream media could offer, especially (though not limited to) the Silver Lake area in which KBLT was based. Although the station’s operations are the core of the film, not the music itself, there’s also much period detail of the era’s alternative rock scene, and how much different the industry was a generation ago, when physical product still ruled (and took up much of Carpenter’s living space). Some of the bands heard on and playing in support of KBLT were very obscure even by indie rock standards, and there’s also considerable footage (if in snippets) of some of them, in the kind of raw cinematic technique also evocative of the era. (My interview with director Sue Carpenter is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/interview-with-sue-carpenter-director-of-40-watts-from-nowhere/).

4. Everywhere Man: The Lives and Times of Peter Asher. Asher was a British Invasion star as half of Peter and Gordon, though he made his biggest impact on pop music as producer/manager of James Taylor and Linda Ronstadt. Both phases of his career, as well as a few others of less renown, are covered in this two-hour documentary. If you’ve seen Asher’s long-running live show of recent years in which he combines extensive storytelling with some music and film, you know a lot of the material, since the directors often use scenes from his actual presentation, filmed at a San Francisco club. Most people haven’t seen that show, so more of this will be novel to them. And even if you have seen that show (I have, twice), it’s pretty entertaining and informative to see and hear Asher talk about his multifaceted life, interwoven with lots of archival clips and photos, as well as interviews done specifically for this project with Asher and several close associates.

Among those associates are Taylor, Ronstadt, Carole King, Peter’s sister Jane, session musicians like Danny Kortchmar, and less expected names like Twiggy, Pattie Boyd (George Harrison’s first wife), John Dunbar (whose countercultural Indica bookstore and gallery Asher helped with in the mid-1960s), Kate Taylor (sister of James), Eric Idle, and (via a 2006 archival interview) Gordon Waller. An impressive wealth of archival snippets were unearthed, from obscure Peter and Gordon appearances through scenes of Ronstadt and Taylor in their prime (and even one of Kate Taylor onstage). Asher also discusses his brief time as head of A&R at Apple Records, where he first worked with James Taylor, as well as Waller’s hell-raising, the shocking suicide of his father in the late 1960s, and the collapse of his first marriage in the 1970s. As Asher himself acknowledges, he’s rather reserved and unemotional, but still a good and oft-humorous tale-teller, and if he doesn’t blow his own horn much, several others testify to his skills as a producer.

Asher’s post-1970s productions, which include work with Cher, Neil Diamond, and Diana Ross, are barely noted, the 1970s Taylor/Ronstadt era jumping quickly to his brief reunion with Gordon Waller a few years before Waller’s death. As incomplete as this makes this survey, I agree with the decision to focus on the much more interesting parts of his career with Taylor, Ronstadt, Peter & Gordon, and Apple. His brief stint working at MGM Records in the late 1960s isn’t even mentioned, though you can go to David Jacks’s book Peter Asher: A Life in Music for details on that and many other Asher accomplishments the film doesn’t get to. One incident that will surprise many viewers, even those with a good grounding in Asher’s background, is that he initially turned down Linda Ronstadt as a client as he felt that he couldn’t concentrate on developing both her and Kate Taylor’s career at once, though Taylor soon dropped out of the picture and cleared the way for Asher and Ronstadt to collaborate.

As for something that only intense sticklers for historical detail might notice, it seems that in one instance, telling a good story might have gotten in the way of what might have actually transpired. Asher was best man at Dunbar’s wedding to Marianne Faithfull, and says he also had some responsibility for breaking up that marriage by helping introduce Faithfull to Mick Jagger. That marriage took place in May 1965, yet Faithfull first came across Jagger at a party about a year earlier. At least in the way the incidents are presented, the chronology is somewhat confusing and possibly inaccurate, and the deduction that he both helped instigate and disintegrate that marriage possibly overblown.

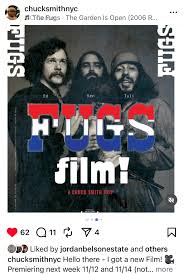

5. Fugs Film! Like some other crucial artists, the Fugs are eminently worthy of a documentary, but handicapped by the shortage of prime vintage footage of the group. That’s a factor in this movie, but to its credit, it unearthed more such material than anyone knew was out there. More importantly, it benefits from recent first-hand interviews with the two surviving members of the Fugs’ core trio, Ed Sanders and Ken Weaver. The third, Tuli Kupferberg, is represented (if rather mildly) by some archive clips. A few of the other Fugs who drifted in and out of their numerous lineups were also interviewed (Peter Stampfel, bassist John Anderson, and guitarist Danny Kortchmar), as well as some people who knew the Fugs well, like Betsy Klein, Weaver’s girlfriend in the 1960s (who did the female vocal on “Morning Morning”), and arranger Warren Smith.

Although this isn’t a totally comprehensive history of the group, it does cover most of the main bases, including highlights from their records; their funny and oft-controversial performances, mixing bawdy humor with penetrating social satire; their participation in the effort to levitate the Pentagon in a 1967 antiwar protest; their activities as poets and Sanders’s New York Peace Eye Bookstore; Harry Smith’s production of their debut album; and their breakup in the late 1960s when Sanders got tired of the effort involved in running a rock band. There are some genuinely good, high-quality performance clips filmed in 1968 in Sweden, though as is so often the case in documentaries, the excerpts are on the too-short side. Quips from a late-‘60s David Susskind interview with the three principal Fugs are also worthy. But the biggest surprises are in the interviews. Weaver remembers watching his stepfather beat his mother to death as a youngster. Anderson, now living as a woman named Jackie, recalls getting a frosty reception from the Fugs after he returned from serving in the military in Vietnam, realizing he couldn’t rejoin the group, although he’d tried to get disqualified from service.

There are, however, some interesting aspects of the Fugs’ career that aren’t covered much or at all. These include their sometimes fractious relations with record labels, including ESP, Atlantic (who dropped them post-ESP after they recorded a few tracks), and Reprise; how and why they changed lineups so frequently; and only passing or no mentions of some interesting members, like guitarist Jon Kalb (brother of the much more famous Danny Kalb), Charlie Larkey (later husband of and collaborator with Carole King), Ken Pine, Vinny Leary, and Lee Crabtree (as well as producer Richard Alderson). Some of this is detailed in Sanders’s autobiography Fug You, but as this 83-minute documentary isn’t overly long, there could have been room for more. (My interview with director Chuck Smith is at http://www.richieunterberger.com/wordpress/interview-with-fugs-film-director-chuck-smith/.)

6. Hung Up on a Dream: The Zombies Documentary. The Zombies were a great group, and this is a good if imperfect documentary. The good stuff: all four of the surviving members were interviewed, with the late guitarist Paul Atkinson represented by an interview with his daughter and quite a few compliments about him from the other Zombies. Singer Colin Blunstone and keyboardist Rod Argent get significantly more screen time than bassist Chris White (who was the Zombies’ other primary songwriter besides Argent) and Hugh Grundy, but no one’s limited to skimpy time. In keeping with their genteel image, they are polite and articulate, with perhaps fewer internal tensions than any other major British Invasion band, other maybe than their fairly mild disagreements about whether they should have broken up in the late 1960s. An unavoidable limitation is the lack of vintage film footage, especially if you don’t count clips of “She’s Not There” and “Tell Her No,” though fairly brief excerpts of performances of those two hits and a few other songs were excavated. The pace is fast and the stories interesting and invitingly told, and while there’s the usual drop-off in momentum when things move past the 1970s into their late-life awards and revival performances, that final section isn’t overly long.

As for the imperfections, there could have been more coverage of their extensive body of quality work besides their two big mid-1960s hits and the 1968 Odessey and Oracle album (which is extensively detailed in respect to its recording and belated appreciation as a classic). Here are two important areas that would have been worth a few minutes: their extensive series of excellent flop mid-1960s singles. Were there any they were especially proud of, and how did they feel about such excellent work failing to sell or even gain much recognition at the time? That issue doesn’t come up, and maybe more seriously, what made them most different from the many other British Invasion groups isn’t discussed either. It’s worth a bit of time to note they used minor melodies more extensively than anyone; had haunting harmonies in addition to Blunstone’s fine distinctive lead vocals; had one of the best instrumentalists of the era in Argent; and that while White didn’t write any of their three hits, he was nearly on par with Argent as a songwriter.

You do hear a lot about their strange tour of the Philippines, and in a related subject, how little money they saw in the 1960s and how badly they got ripped off. That’s interesting and not related in an unduly sour manner, and there’s some attention paid to Blunstone’s solo career in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and Argent (the band’s) relatively successful run during that time. It’s revealed that Blunstone was adopted and raised by the sister of his birth mother, though he didn’t learn his birth mother was the sister of his adoptive mother until well into adulthood. As for a worthwhile sentimental concluding note, Rod Argent observes that while they appreciate their eventual recognition as an important act, the big success was that they remained friends all their lives.

7. Becoming Led Zeppelin. One of the most popular documentaries of 2025 covers the roots, birth, and emergence of Led Zeppelin with their first two albums, ending in early 1970. I’m not a Led Zeppelin fan, which is yet another sure way to lose some friends on social media. However, I’m a big fan of the Yardbirds, from whom Jimmy Page transitioned to forming Led Zeppelin. I’m also interested in his pre-Yardbirds work as a session man, and also the much less documented pre-Led Zep work of the other three members. Much of the first hour of this two-hour film is devoted to those pre-1969 years, with extensive first-hand interviews with the three surviving members (the fourth, John Bonham, is represented by audio from a non-video interview he did). There’s a wealth of sound and silent footage of early Led Zeppelin, some of it rarely seen or unseen before this was released. There’s also some scarce footage of artists with whom they were associated, including the first I’ve seen (though silent, with an official recording serving as the soundtrack) of Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, as well as less likely suspects like Lulu, producer Mickie Most, and Shirley Bassey.

Led Zeppelin fans, of course, will be thrilled with both the footage and the articulate, detailed memories of Page, Robert Plant, and John Paul Jones. Refreshingly, they (and Bonham, via the audio interview) are the only interviewees, telling their story themselves without testimonial endorsements about how great and significant they were from much younger rock stars and other celebrities. In large part because I’m not a fan of the group themselves, the second part was less effective for me, with some segments filled out by footage of period non-music news events and ’60s rock culture. (For what it’s worth, some shots of audience dancing at the Fillmore West are from a 1966 film clip of Jefferson Airplane, not from a Led Zeppelin show or even another Fillmore concert from the time Led Zeppelin were active.) To its credit, instead of restricting itself to brief snippets, some performances of their early songs are shown in total, or nearly total.

As long as this is, there is much more that could have been said, though knowledgeable fans have found the information elsewhere. It’s not mentioned, for instance, that when Page joined the Yardbirds, he played bass at first, then moving to share lead guitar duties with Jeff Beck. Controversies about songwriting credits for some of their early tracks aren’t covered, though Page mentions the Yardbirds’ version of “Dazed and Confused” (later of course also done by Led Zeppelin) was “inspired” by singer-songwriter Jake Holmes, and Plant says he came up with Willie Dixon-type lyrics for part of “Whole Lotta Love.” It’s interesting that Page and manager Peter Grant determined to concentrate on the US market even before their first album came out, and that it was recorded in total before a deal was signed with Atlantic Records. It’s odd, though, that while it’s stated that Page had a drummer in mind before Bonham was suggested, that drummer isn’t named; some sources say this was B.J. Wilson of Procol Harum, others that it was the much more obscure Paul Francis. It’s also odd to hear Page remember devising the abstract instrumental break of “Whole Lotta Love” to ensure it wouldn’t be used as a single; as many people and surely Page himself know, it was indeed a big hit single in the US, though an edited version was supplied to radio stations.

8. Sunday Best: The Untold Story of Ed Sullivan (Netflix). This isn’t an overview of the famous TV host’s career, though it includes a lot of detail about it. It focuses on one specific part of his contributions — his openness, perhaps even eagerness, to spotlight African-American performers on The Ed Sullivan Show. His professional stance against bigotry dated back to his time as a newspaper columnist, and during the program’s long run from the late 1940s through the early 1970s, he had many black entertainers on his show. There are clips (brief; the documentary runs about 90 minutes) of quite a few, including the Supremes, Louis Armstrong, Bo Diddley, Nina Simone, Gladys Knight, Stevie Wonder, and the Jackson Five, as well as interviews testifying to Sullivan’s contributions from Berry Gordy, Smokey Robinson, Dionne Warwick, and others. Some archival interviews with Sullivan make clear his commitment to airing African-American entertainment, even under some pressure from sponsors and affiliates (especially from the South) not to. Numerous scenes of Sullivan hand-shaking and embracing black guests on air also make clear his comfort with giving them a showcase.

Although the documentary’s not overly long, it’s filled out some with contextual scenes of Civil Rights activism from the time, as well as his airing of the Beatles in early 1964 and the program’s decline in popularity by the time the 1970s began. Smokey Robinson particularly hails Sullivan’s love of Motown artists, and how much their guest appearances helped soul music and the image of African-Americans in general. Sullivan’s particular taste in and passion for the music he presented isn’t examined, or perhaps even known to a great extent. His sincerity in giving blacks a platform on national television is evident, however, and though some quick cuts between eras and different forms of entertainers gets rapid at times, it’s not unduly hectic.

9. Devo (Netflix). Getting its festival premiere in 2024, this wasn’t widely seen until it got onto Netflix in 2025, hence its qualification for this list. If I was more of a Devo fan this would be higher on this list, but it earns a place in the Top Ten as it’s well made and has points of interest even for those not enamored of their music. There are extensive interviews with members, particularly Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh, and many archival performance clips, going all the way back to 1973. Plenty of archival interviews are also incorporated via both film and sound recording voiceovers, and naturally there are clips from some of their numerous videos, from early DIY productions through the MTV era. These again have their entertainment value even if you don’t have their records, poking as they often do at institutions, consumerism, and the general deterioration of civilization. The pace is fast to the point of verging on over-hectic, though such rapid-fire imagery is in keeping with much of their aesthetic.

Devo’s music and records come in for a lot of coverage, including their mixed experience working with producer Brian Eno on their first album (as Eno wanted a greater creative role than was reflected in the results), their breakthrough to wider visibility with their Saturday Night Live performance of “Satisfaction,” and of course their huge hit “Whip It,” which was kind of a fluke after a radio DJ in Florida started playing it after a different song had been chosen for a single and flopped. Their roots in the political turmoil at Kent State in the early 1970s gets a lot of attention, as does their use – overuse, in the view of listeners such as myself – of irony and their infiltration, to some degree, of their underground approach into mainstream culture. There are also insights into/examples of the difficulty of an outsider band working within the major label corporate music business, whether it’s conflicts between Virgin and Warners Records in delaying the release of their first album; Warner Brothers’ general impatience with their idiosyncratic way of doing things; and MTV rejecting a suggestive video after playing many Devo videos in the network’s early days.

10. We Want the Funk! (PBS). Funk’s evolution and impact is satisfactorily covered by this nearly 90-minute doc, though there might be a little too much academic analysis by some of the talking heads. Although its echoes in rap and some more modern artists are touched upon, the emphasis is properly on funk pioneers of the 1960s and 1970s. James Brown, Parliament/Funkadelic, and Sly & the Family Stone all get significant airtime and short vintage performance clip excerpts. So do some others, like LaBelle, Bootsy Collins, Prince, and – commendably, as some projects might overlook them – Afrobeat pioneers Manu Dibango and Fela. While there aren’t too many first-hand recent interviews, George Clinton Nona Hendryx, and David Byrne offer some thoughts, and some academics and authors weigh in with funk’s relationship to and reinforcement of African-American identity. Of course some of the less successful and/or critically respected funksters are lightly covered or not covered, but the judgment on whom to focus is sound. Of course, like many documentaries on PBS or elsewhere, the subject merits a more extensive multi-part series if anyone’s up to it.

11. Janis Ian: Breaking Silence. Known to many listeners only for her two big hits “Society’s Child” and “Seventeen,” Ian had a very long career spanning more than half a century, though she recently stopped performing owing to vocal problems. Those two songs get a lot of coverage in this well-made documentary, whose musical focus does emphasize a handful of her compositions, also including “Jesse” (covered for small hit by Roberta Flack) and “Stars.” Ian was interviewed for the film, though her presence is felt more by numerous voiceovers than clips in which she appears. Also heard from are some notable associates and peers, like producer Brooks Arthur, Joan Baez, Arlo Guthrie, Lily Tomlin, and girlfriends and boyfriends. Snippets of a good number of archive clips are present, including her performance of “Society’s Child” on the 1967 Leonard Bernstein-hosted network TV special on pop music that helped the song become a hit single when its controversial lyric about an interracial relationship was limiting its airplay. Numerous gaps not covered by vintage footage or photos are filled in by silent reenactments, which are too heavily used, but not so much that they make for a serious flaw.

A nearly two-hour documentary on any major musician can’t cover close to everything. But there’s much this doesn’t address so much, like her teenage songs besides “Society’s Child” and her time when she was struggling to even get a record deal after being classified as a one-shot child prodigy. Some of that’s filled in by her autobiography. But this does have some unusual stories that will surprise people, like how “Seventeen”’s ascension to hit status was helped when copies of her record were mailed not just to radio programmers, but specifically to women—to their wives and any women working at radio stations. And earlier, when producer Shadow Morton gave her the option of changing the lyric “black as night” in “Society’s Child,” explaining that would remove an impediment to it becoming a hit (Ian didn’t change the lyric). There’s also her near-descent into poverty when it was discovered someone in her management had been fleecing her for years, forcing her to pay off the IRS for thirteen years before she was clear of debt. While like many documentaries this loses some momentum as her more recent years are covered with less depth, but it also recounts her public championing of LGB identity, the archiving of masses of her material at Berea College, and her regrettable need to stop performing (though not writing) when her vocal cords were damaged a few years ago.

12. King of Them All: The Story of King Records (PBS). It doesn’t have the name recognition of Motown, Stax, or Chess, but the Cincinnati-based King label recorded a lot of important soul, R&B, early rock’n’roll, and (mostly in its early days) country music from the mid-1940s through the late 1960s. Lasting a little under an hour, this PBS documentary covers the essentials of the company’s history well, though it inevitably misses out on detailing some notable performers owing to its length. King’s cantankerous founder-owner, Syd Nathan, is represented by some audio interviews, and while his autocratic nature is testified to by some others involved in the label, his dedication to building a powerful independent company is too. So is his willingness to work with African-Americans and southern whites of modest means at a time when that wasn’t encouraged in a more segregated society. So is King’s determination to fulfill the tastes of what were considered minor ethnic markets that weren’t being catered to by major labels, and its role in sparking rock’n’roll by having country artists cover R&B songs, and vice versa.

James Brown was King’s biggest star, and he’s the artist that gets the most coverage here, including with some archival clips that, in keeping with the usual public television format, are short snippets. By the mid-1960s he pretty much was carrying the company, which came to an end when Brown moved to Polydor and Nathan died near the end of the decade. Besides some historians commenting upon King’s significance, interview subjects include Hank Ballard, who discusses his controversial “Work With Me Annie” records and his original version of “The Twist” in footage that must have been shot a long time ago, as he died in 2003. Early King country pioneers like the Delmore Brothers and Merle Travis get some time via recordings heard on the soundtrack and photos. Yet other quite significant R&B/soul/blues artists on King are barely mentioned or heard, including Freddie King, Little Willie John, Bill Doggett, and the Five Royales. King’s legacy is worth a longer or multi-part series, as unlikely as it is that it will be honored with the kind of four-hour treatment given by HBO’s Stax: Soulville documentary.

13. Billy Joel: And So It Goes (HBO). This two-part, approximately five-hour documentary would rank higher if I was more of a Joel fan, or a fan of his music to any significant extent. It’s on this list not just because it’s pretty well made, with plenty of recent interviews with Joel; interviews with close associates covering his whole career, including band members and all of his wives, the first of whom managed him as he shot to superstardom, the second of whom (Christie Brinkley) is extremely famous in her own right: and lots of footage and photos spanning his entire professional life. Much (though not all) of it’s pretty interesting no matter what your take on Joel, particularly the wealth of struggles and professional setbacks he faced in gaining fame (and sometimes, after he became famous). It even goes way back to the two bands he made records with before going solo, the Hassles and Attila, and these aren’t just mentioned in passing, but discussed in reasonable depth. Indeed much of his music is discussed in reasonable-to-considerable depth, including of course his most famous songs and hits, of which there are many.

A few of the obstacles Joel faced — some familiar to those who come to this knowing a lot about his career, but much of them not known, or known much about — including tapes for his first album getting sped up, much to his dissatisfaction, particularly in the vocal department. Some of his producers (though not Phil Ramone) come off pretty badly in their insistence on doing things like that, particularly Artie Ripp and, later, Chicago producer James Guercio. Joel turned down George Martin as producer since Martin didn’t want to use his band, though this actually paid off as when he used Ramone instead, he made the LP that made him huge (1977’s The Stranger). A former brother-in-law manager comes off as quite the villain, though his first wife, Elizabeth Weber, is hailed for assertively playing a vital role in pushing Joel over the top in her years as his manager. If you want some personal intrigue, there’s much, especially as Weber had been married to Joel’s closest pre-solo bandmate when Billy and Elizabeth began their relationship.

The tale gets less interesting after the last of Joel’s most familiar batch of songs on 1983’s An Innocent Man. That still leaves time for two more marriage breakups, subsequent wrestling with alcoholism, and his decision to stop writing original material and, eventually, retire from performing, though he walked back on that to some degree. And there are some reflections on the joys of family life that are common to such celebrity profiles, as well as notes about how the low regard in which he’s held by many critics is countered by his phenomenal popularity. Some of this could have been cut, and indeed some other parts could have been cut down too. But at a time when many American Masters-like studies don’t go deep enough, here’s one that doesn’t shy away from covering multiple sides of the artist at considerable length.

14. The Disappearance of Miss Scott (American Masters). This nearly 90-minute episode of American Masters covers the life and career of jazz pianist/singer Hazel Scott. Her style of mid-twentieth century jazz isn’t among my main interests, but her accomplishments were noteworthy, and this documentary has a good balance of coverage of her musical and social achievements. She integrated some elements of classical music into her fairly mainstream jazz swing, and worked in some all-women bands when such ensembles were fairly rare. At the beginning of the 1950s, she was the first African American to have a syndicated television show. She was also married to Adam Clayton Powell, the famed first black Congress representative from New York State. She also appeared in some movies, although her insistence on not doing a scene with fellow black actors whose wardrobe had been deliberately dirtied cost her Hollywood advancement. She was also among many entertainers who were blacklisted in the McCarthy era. There aren’t many people who knew Scott left, but her son is among the people interviewed, and there are plenty of archival performance (and some interview) clips of Scott herself dotting the program.

This film listed below came out in 2024, but I didn’t see it until 2025:

The Yardbirds: In Their Own Words (Sky Arts). There was a BBC documentary about the Yardbirds almost thirty years ago, but this is both longer (at nearly an hour and a half) and more comprehensive. A good number of band members, associates, and figures influenced by the Yardbirds were interviewed for the film, most especially original drummer Jim McCarty, original bassist/producer Paul Samwell-Smith, and Jimmy Page. Jeff Beck is represented by a good number of archive interviews, though unfortunately Eric Clapton is only seen talking about the band briefly in one. To add to the list, interviewed for the documentary were also Simon Napier-Bell, who managed the group for about a year; late singer Keith Relf’s sister Jane, who’d sing with his post-Yardbirds group, Renaissance; Relf’s wife; and, testifying to their influence, Alice Cooper, Brian May, and Lenny Kaye. While the clips used in archival footage of the band on film are brief, they are numerous, and include the group in their various lineups with Clapton, Beck, and Page, even managing to put in much of their legendary appearance in Blow-Up. Most of their hits and most famous songs are represented in these, though the absence of even discussion of the “Still I’m Sad”/“Evil Hearted You” single is unfortunate. Some of the pictures and home movies are unfamiliar.

The core story of the group will be familiar to many listeners, but even so, it’s good to hear the tale of their unlikely journey from blues group to psychedelic pioneers in their own words. And most of it is in their own words; there’s little narration aside from a prologue, and not much in the way of unnecessary talking heads who weren’t involved in their career. Along the way, the touchstones include how they brought improvisation into blues-rock; the departure of Clapton for blues purism and replacement by the more adventurous Beck; the incorporation of Indian influence; their one album, 1966’s The Yardbirds (aka Roger the Engineer), where they were able to have a reasonable amount of time to record a full LP the way they wanted; their disappointing Page-era Mickie Most productions, for which criticism is not held back; and how Page’s experience in the Yardbirds help set the success of Led Zeppelin. Of particular interest to me were Simon Napier-Bell’s comments, as in his first memoir, he’s pretty flippant about the whole mid-1960s British music scene, as though it was a bit of a joke, though he did write that the Yardbirds were among the few acts who really mattered. Maybe he was writing in that style for effect, but in the documentary, he has serious and accurate comments about the group and the strength of their music. As Jane Relf hasn’t been interviewed too often, her contributions were also welcome. Sure it would have been nice to have more extensive discussion of managers Giorgio Gomelsky and Peter Grant, or of deep tracks like the few they managed in the Page era that were really good like “Glimpses” and “Think About It,” though their version of “Dazed and Confused” is noted (and their French TV performance of it excerpted). It is too bad, however, that this documentary for the Sky Arts channel is difficult to access in the US.

Hi Richie,

Thank you for including EVERYWHERE MAN on this list!

Look for it in a “Theater near you” sometime in June…

All best and happy holidays!

Dayna

Geller/Goldfine Productions