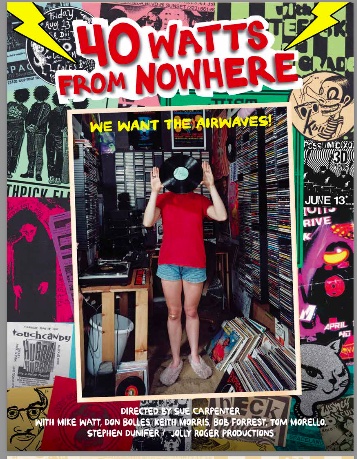

In 2004, Sue Carpenter’s engaging memoir of running a couple pirate radio stations in the mid-to-late-1990s, 40 Watts from Nowhere, was published. About twenty years later, she’s directed a documentary of the same title based on those experiences. While it naturally covers a lot of the same ground as her book did, it’s not simply a retelling of that narrative. It draws on a lot of footage taken at the time for an unrealized documentary on the Los Angeles pirate station KBLT, which was run out of her home.

That footage includes many of the DJs and others affiliated with the operation, as well as some performances artists did for or at the station. Some pretty well known musicians appear in those guises, if fleetingly, including Mazzy Star, Mike Watt, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. More interesting, however, are the numerous interviews done with station personnel at the time and, crucially, quite a few done specifically for this new documentary. Carpenter herself is extensively interviewed both in the vintage footage and the material shot for her own film.

Carpenter had briefly overseen a pirate station in the mid-1990s in San Francisco before moving to Los Angeles to more or less helm the much more well known KBLT for a while in the late 1990s before it was shut down by the FCC. KBLT specialized in broadcasting alternative music of all kinds (if primarily alternative rock, judging from the film). The memories of doing the groundwork for getting on the air, as well as the fun and sometimes rocky times putting music on it to considerable enthusiasm from adventurous locals, are entertaining on their own.

An important message that also comes through, however, is how the station helped build a community of people determined to provide something different from what mainstream media could offer, especially (though not limited to) the Silver Lake area in which KBLT was based. Although the station’s operations are the core of the film, not the music itself, there’s also much period detail of the era’s alternative rock scene, and how much different the industry was a generation ago, when physical product still ruled (and took up much of Carpenter’s living space). Some of the bands heard on and playing in support of KBLT were very obscure even by indie rock standards, and there’s also considerable footage (if in snippets) of some of them, in the kind of raw cinematic technique also evocative of the era.

KBLT was shut down by the FCC in 1998, in a dramatic scenario where Carpenter raced to the roof of the building on which the transmitter was located when the station went off the air. I spoke with her about the film in July 2025, not long after it screened at the Roxie in San Francisco.

Why did you want to do a film of the same story you wrote about in a book?

I had no intention ever of making a movie. I thought the book was going to be the definitive account of the radio station. I wrote it shortly after the radio station was over, just because I have a horrible memory, and I needed to get everything down. And I just thought that was it.

But that book got rediscovered by “experience designers.” They design experiences at theme parks. They also have their own side business of experiential theater. They heard about three years ago that there had been a pirate station in Silver Lake, and there was a book about it. They found the book, tracked me down, and said they wanted to make it into this experience.

I helped them re-create the space, and it was right around the corner from where the radio station had been. It looked so much like the old station, because it was in the old neighborhood. I started reaching out to some of the DJs and said hey, let’s have a reunion and do a livestream with a bunch of the old DJs. So we did that – Mike Watt was a part of it, Keith Morris, like the celebrities, and a lot of the other DJs whose shows I really enjoyed.

Through that, because I was reconnecting with all these DJs that I hadn’t seen in years, somebody just piped up and said, “You know, I’ve got twelve hours of video. You can have it if you want. I don’t know if it’s worth anything. I was just cleaning out my garage, and I was about to throw these anyway. But you can have ‘em.”

I went through the tapes, and I was shocked at what was there. He’d started shooting in the summer of 1998, which was arguably our peak. Then we had an FCC scare and went dark, and then we came back on the air. He sort of captured the arc of the story. He did a sit-down interview with me that I had no recollection of doing. He had the original engineer for the station, who I’d completely lost touch with and couldn’t track down. He had the helicopter ride that we took to sort of scout rooftops [on which to put the transmitter]. He had Sunset Junction, a big street fair [at which KBLT had a booth]. He just had like the whole arc of the story, and I figured I could flesh it out with modern interviews that tell the story completely.

I started as a print journalist, moved into radio journalism, and now I work in broadcast TV. Although I don’t do a lot of work on the broadcast side, I’ve been trained. I have done some broadcast features where I shot, edited, like did everything. I just thought I could do it. I could make a movie with what I had.

This is your first film…

First and only, ever (laughs)!

What did you want to make different about the film than what is read in the book? Not just the content, but also the approach.

To be able to see it…because we did not realize how the world as we knew it was about to end. The analog era, the “have an idea, make it happen, it doesn’t matter if it you make any money” sort of idea. The analog, the creative ‘90s. I had all this footage that showed that.

The other thing is, I was very close to my own story when I wrote 40 Watts from Nowhere the book. It really lacked a lot of self-awareness, I think. What was weird about that book is that men really seemed to like it. Women did not like it, because they read the book, and didn’t feel like they understood who I was. I feel like it was because I was guarded about who I am. I think the difference with the film is, working with the editor I worked with, she really pulled out the emotional part of the story—not just for me, but in the community, and of the era.

I didn’t think of the book as something that would have that difference between men and women readers. I can see the reaction that readers might not know as much about you as a person. But why the reaction would be so much greater for women, I don’t know.

I think it’s because the book was billed as a memoir. It didn’t really go into me so much. It was really a memoir of the radio station. The reviewer who wrote about it for the Chicago Tribune when the book first came out, that’s how he characterized it. I feel like that was exactly accurate.

If you read memoirs, they’re really intense. Because people “go there.” And I’m just a guarded person. I wouldn’t even have known how to plumb that.

What surprised you so much when you looked at the footage that was taken in the late 1990s? Not just what you didn’t remember, but the perspectives, where you and others at the station might be thinking of the experience in a different way 25-30 years later?

Just the joy that people had. It’s not like I didn’t know at the time, or think about that in retrospect. I feel like that’s really palpable, and it really struck me. A lot of it was just the excitement of seeing it. Like you have in your mind’s eye what happened, but then to actually see it was fun. Just like, oh, this is how I remember it being.

There are a bunch of snippets of footage of obscure regional bands who were barely filmed at all anywhere, as far as I know. Did that strike you when you put together the movie?

That was hard. Because back in the time, almost nobody did have a camera. There was a guy who has since passed away, Rush Riddle. He had an apartment down by the University of Southern California, where he used to have a lot of live shows with all of the bands that kind of lived in that area at the time, and would perform at the official clubs. But he had this space where bands could come and play, and there’s hours and hours and hours of footage of a lot of the bands from the scene that were shot. They’re not very dynamic, they’re from one angle for hours on end. But that’s all been given to USC to archive. I don’t know where that currently stands.

Then there’s some other footage that some people shot. They put it out on youtube, and my producer tracked them down, because he’s more connected with that scene than I am. They let us use it. But it was sort of few and far between. There’s just very few people who actually have [such] footage of the band playing live.

A lot of these bands never went on to achieve anything, really. But it does sort of capture the spirit of the era through these different bands.

What was the difference between launching a station in San Francisco and then the one in Los Angeles?

I think the motive in the beginning of both stations were the same. It was just to see if I could do it and create this alternative space for the kind of music I wanted to hear. What’s weird about San Francisco is that it took off way faster than the station down in Los Angeles. It took off like from the get-go. People were finding it, tuning in, listening, and calling.

I was hoping to have that repeat experience when I went down to L.A., not knowing anybody. That is not how it happened in Los Angeles at all. Which could have everything to do with me being the DJ and just doing a shitty job (laughs). I’ve always said that I was the worst DJ on my own station, which I think is very true.

But all the people from the community came in through Brandon Quazar, just like the movie says. I’d not had anything to do with Quazar for decades when I reached out to interview him for the movie.

When it started to take off, as you hit different milestones, it sort of reinforced what I was hoping to achieve, which was be a place where people could play anything. But it was realized in a better way in Los Angeles, just because of these true music lovers who had great collections and great sensibilities. It played out way better than I ever would have expected it to.

Maybe it was a blessing it took off slowly in Los Angeles, because it gave you more time to operate under the radar. Maybe in San Francisco the hammer would have come down from the authorities much quicker.

That’s entirely possible. It was a slow burn for a while, and because of where I was located in Los Angeles, we didn’t have a lot of range. It was very much in the neighborhood itself.

How much of your motivation was music, and how much was activism, making a statement about the importance of providing alternative media?

I was very hesitant to identify myself as an activist when I started up in San Francisco. But then in Los Angeles, I think that became a bigger part of it. As the movement was growing, I was actually reporting on it myself as a freelance journalist, and sort of coming into contact with the scene in Florida, or Pete Tridish [of pirate station Radio Mutiny] in Philadelphia. It was part of my awakening.

The scene in San Francisco was very political and not musical, and in Los Angeles all the stations were about music. They weren’t about politics. Weirdly, I sort of feel like I became – not overtly, but internally, within myself, more of an activist. Like, just keep it going, we’re fighting The Man and we’re winning. That’s sort of how I felt.

But I would not have characterized myself as an activist in the same way [as] Stephen Dunifer [of the pirate station Free Radio Berkeley, interviewed in the film]. Those people were like out there, “come and get me.” I was like, “don’t get me” (laughs).

What do you think the difference was between your station and the several community and college stations in L.A., in its format and content? Some of them did offer really uncommercial material.

I feel like it probably had more of a real reason to exist in San Francisco. That’s because KUSF [the station of the University of San Francisco, which offered alternative programming until the university sold its frequency to classical music programming in 2011] switched from music programming at 6pm to community international programming in different languages at that time. So that was why I went on the air when I did, other than having a full-time job at the time too. I [felt] like it really was necessary to fill that void, because there was no other alternative radio station. Live 105 definitely was not it; that was commercial. But [to have a station] that sort of did this KUSF-style programming.

When I came down to L.A., I didn’t know anything about L.A. But I was quickly schooled in the stations that you’re talking about – KCRW [an NPR affiliate broadcasting from Santa Monica College], KXLU [a college station broadcasting from Loyola Marymount University]. Some of the DJs on KXLU were actually DJs on my station too. I feel like the M.O. that I had, like playing stuff outside the norm, was already being done by those other stations, especially by KCRW at that time.

But I had tried to be a DJ on KCRW and on KXLU, and you couldn’t. Because the policy of the college radio stations in Southern California was different from San Francisco. I had volunteered and gotten on the air both at KALX in Berkeley and at KUSF. Well, I never got on the air at KUSF, but you could get in the door. They did not have the open-door policy in Los Angeles at the college radio stations. You had to, at KXLU, be a student. And at KCRW, I still don’t understand how they had these people who had these DJ slots for decades. It’s almost impossible to get on.

But their musical selection was a little bit softer, I think. Like it was within parameters. There were no parameters at my station. You could play something completely off the rails, like Don Bolles, right? [Bolles, drummer in early L.A. punk bands like the Germs and 45 Grave, DJd on KBLT, and is shown in the film’s vintage footage airing the Golden Orchestra’s absurd “The Chocolate Cowboy” on one of his shows.] Whether you wanted to listen to that is another question.

When Mike Watt was DJing, [in the film] he plays something from a cassette by the Screamers. They were a legendary early L.A. punk band that never put out any records. Only very recently has anything come out by the Screamers that’s commercially available. That’s something cool he could offer, especially being an insider on the scene, that maybe couldn’t have gotten on college or public radio, or seldom would have. It’s one example of how the station could offer something that couldn’t have been found elsewhere. Even if you heard the Screamers elsewhere, to hear Mike Watt talk about them when he played them was a unique experience.

[When] a few years ago I brought the DJs back for that livestream reunion, Keith Morris’s concept for his show—he was like begging me to bring the station back, because he wanted to continue this concept. He’s from L.A., so in the ‘70s and in the ‘80s, he was just out on the Sunset Strip, which is where the rock clubs were. He would go to shows all time, and he had all these stories to tell. I love that. That was Watt too. Having these guys who were locals who went to become legends, that’s what they would do.

I think the sense of community as the station grew was reflected more strongly in the film than the book. Much of what community you see in the film in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles was sparked by the station, even for people who didn’t have a show there.

Yeah, but it was also happening in the music venues. I have a very specific perspective on it, because I was at the radio station from the get-go, within a month of moving down there. So my whole social circle sort of formed around my running this radio station. But I think a lot of people knew each other just from being in the bands, supporting their friends in other bands. A lot of it was happening in the clubs, at private shows in people’s houses.

The community aspect that is more prevalent in the movie really came up in the modern interviews that I was doing. How fondly people felt about it, even thirty years later. And how connected they felt, how the station itself felt like a center for their social life. I think that’s why you’re sensing more of it coming through in the film. Also, my editor drew out the emotional part of the story.

The film vividly reflects how logistically difficult it was to run a station out of where you were living. There’s that scene that notes a lot of the station was between the toilet and your bed. That’s a lot of personal sacrifice to accommodate something that needs a lot of raw material to function, even if it’s nothing like how much was used by stations like KCRW.

I definitely marvel at it. I almost don’t even recognize myself for tolerating it. But my take on it is, [the station] started [broadcasting] 8 to 10pm. Two hours every night, seven days a week. It’s sort of like the frog in boiling water. The frog is in the warm water, the frog is fine. Then you need to keep upping the temperature, and then eventually the frog wants to jump out of the water, the frog dies.

I feel like growing the station the way that I did, it was easy in the beginning, ‘cause it was just regular hours, like when I would normally be up, and when you would be hanging out with your friends. As the station became more popular and grew out to the point where it was around the clock, that was pretty intense. I definitely don’t know how I would have been able to continue like that, to be perfectly honest. It was sad when the station was over, but on some level it was like, “make it gone, get these people out of here.”

But the reason I did it that way was there was no money to have a separate space, like a rented space. I suppose we could have talked about the financial model for that. Back then, rents were cheap and maybe we would have been able to do it. But it didn’t really occur to me at that time.

It was interesting to see that the problems of theft of records, and careless treatment of equipment, were as rife at your small pirate station as they were at established community and college radio stations.

My math on humanity is that 90% of people do the right thing. Then there’s this other group. Like one percent is hell on wheels; four percent, wish you had never met them; five percent you can deal with it. The other 90 are great.

So I don’t feel like I ever knew who those people were who were ripping me off. If they would break something, some people would say hey, I just broke this. But I don’t necessarily think anybody said hey, I’ll get a replacement. I don’t remember that. I’m sure some people did, I just don’t remember.

You had some pretty high-profile artists who were interviewed at the station. Jesus & Mary Chain, the Dandy Warhols, Spiritualized – this is aside from local underground music celebrities like Mike Watt, Keith Morris, and Don Bolles, who I think would have been easier to get on the air. What did those artists think of coming to the station? Did they have a good idea of what the station was and its audience, or were maybe thinking it was a more commercial or had a bigger range than it did?

I so rarely met these bands when they came in. It wasn’t like I was told, hey, Dandy Warhols are coming in. People would just bring people in. I know the guy from Rancid, back when they were a thing, they were there. There was a ton of bands. I just recently found out that Hope Sandoval from Mazzy Star was actually at the station with Jason Pierce from Spiritualized. I had no idea. I literally found this out within the last six months.

Jesus and Mary Chain, I’m not sure what they were told. I think they were supposed to go to a more mainstream station. But I think some of them sort of liked the idea of coming in to a place that was a little bit more underground. ‘Cause it felt more authentic, it felt more real. It would be sort of like, going into a commercial station, you sort of have to be on, and on your best behavior. But coming in to a place like our station, they could just be whatever. It wasn’t being recorded to your knowledge. It was just, you came in, you did your thing, you left.

I think most of them knew that they were coming in to a pirate radio station. The one artist that I remember who came in who really didn’t understand why we needed to exist was Wayne Coyne from Flaming Lips. I remember having a conversation with him, and he really challenged me on like, why? He was the one artist who I don’t think got it. Which is weird, considering that he’s like a far-out kind of guy.

I know someone who was on KUSF in the early 1980s who felt like some of the touring artists being interviewed actually didn’t know where they were because their schedule was so hectic and they were being told do go here and there doing interviews between concerts, Some of them thought KUSF was going to be a much bigger station than it was, and didn’t realize it had a small range and was a tiny couple of rooms in the middle of a college campus with tons of other unrelated things going on. Did you have reactions like that with the musicians who came to the station?

It was clearly in a house. I think they were aware of where they were. But I think it’s the same thing. Like, we were slotted into a schedule among many places that they were supposed to be.

When you had the benefit for the station when it was operating, that was cool to build support for and awareness of the station. But were you thinking at the time, that’s great to build visibility for the station, but at the same time make it more likely you’ll get busted?

Yeah, that was such a clusterfuck of emotions. Because it was super exciting to be doing a show that was out in public that had that lineup, that was getting media attention. It was sort of like that double-edged sword of you want to attract the right people, not the wrong people. But obviously that is not in your control. If you’re going to be public like that, if you’re going to advertise that, if you’re going to have people talking about it, you don’t know who’s gonna be hearing it. And just showing up as a fan, versus showing up as, “we’re gonna shut you down.”

Luckily, that isn’t what happened. We got some very high-profile media in ’97, that’s when it started. That’s when I think we sort of got put on the FCC’s radar. Through the media, not necessarily because of the show. It was the media that came out of the show.

Do you think it was a source of satisfaction to the bands at the benefit concert done for the station, and who went on air at the station, to be feeling like they didn’t have to be doing this for promotion, but they wanted to because they believed in what stations like yours were doing? Because as a well known name, like Mazzy Star and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, they could promote something that really needs promotion, even more than KXLU or KALX?

I don’t think Mazzy Star really knew that — when I talked to her [Mazzy Star’s Hope Sandoval] after the [benefit] show, I don’t think she really…it was [like], “show up, appear at this time.” I don’t necessarily think that she was presented with this as a benefit for a pirate radio station, are you on board? I think her people did. I don’t think she necessarily knew.

Red Hot Chili Peppers, making this movie brought up the debate about, who got more out of them coming by the station? I feel like we got more out of it, because it upped our profile and our credibility. This is hindsight for a lot of the DJs and their very punk ethos. They’re like, “Oh, no, they got so much more out of it. Because we were so cool.” (laughs)

I agree the station got more out of it, though I guess it could have been said, “The Red Hot Chili Peppers are so big they don’t need to do this, but doing it made them seem cooler and more underground.”

[People] also accused us of selling out. We wouldn’t normally play their music on our station. That wasn’t what a lot of the DJs would have been playing.

I’m still wondering how Mazzy Star got on the benefit if they didn’t know what it was for or what the station did. They weren’t as big as the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but they were pretty well known and on a big major label, Capitol. Capitol’s headquarters [the famous circular Capitol building] is about five miles or less from where the station was.

Yeah. Laurel Stearns, who’s in the film and was a DJ, she has magical powers. She’s just a very beloved person that can make things happens. I mean, lord knows what she said. But she was friends with Mazzy Star’s manager.

It seems like something someone managed to sneak through. They’d been on Capitol for a while, and it doesn’t seem like the kind of publicity the label would go after, or even approve, because they wouldn’t have wanted to be associated with a pirate radio station.

That’s why I think it was done with outside management, not having to do with the label at all.

One of the most effective scenes in the film was when the station had a booth at Sunset Junction, and you were literally being drowned out by the sound coming out of the speakers in a nearby booth from the commercial dance music station Groove Radio. It’s almost a literal representation of stations with tiny signals like yours being drowned out by big commercial ones. Not just the signal range, but the different message that smaller stations have from commercial ones.

I felt really lucky when I saw that whole sequence. It was like yeah, this is like, you actually see it. That was the whole point of the movie – you can see it. It’s like the whole thing in journalism, show don’t tell. So this whole movie was about showing it.

Your line in the movie about getting drowned out by Groove Radio was, “We’re battling this huge radio station. We’re just battling to be heard.” It’s aside from just battling to exist. Even if you had a license, because of your small range and the nature of your music, you’d be battling to get an audience.

I feel like Don Bolles’s favorite thing to say about the station is, “KBLT, the station with more DJs than listeners.” Which probably was true. I don’t honestly know how many listeners we ever had at one time. But everybody seemed to know about it who lived in the neighborhood. How often they tuned in, I’m not sure. We weren’t part of Nielsen.

In the movie there’s a sense of, the bigger you got, the more likely you knew the hammer would be coming down. If you could have operated for at least another year or two, are there things you would have liked to have been able to do with the station?

I feel like at the time, when we got busted, the station was firing on all cylinders, and that’s how I would have wanted it to continue. I would have moved it out of my house. That’s probably the only thing that I would change. But I wouldn’t change the way I programmed it, which was to say that I did not program it. I just had an open door policy, and tried to let as many people come in and DJ as I could.

How is how you went through almost thirty years ago relevant to today, when the means for programming music and public affairs is much different than it was then, with podcasts, streaming, and other things now possible? In some ways the outlets are infinite compared to what existed then.

When you look at it through the modern day lense, it seems like a really ludicrous thing to have done. There is human curated radio being done the way that we used to do it, online everywhere. So there’s a lot of real DJing, like real low-power community radio happening, enabled by the Internet.

What I really enjoyed about my station, and I think would still have a lot of value in the present day, is just the community nature of it. Just a group of people who come together to do something that everybody cares about. I’m disappointed in My Spotify, because I feel like every time that I just want to listen to something, just check it out, which I might not even ever want to hear again, it messes with my algorithm. That’s not cool.

There’s just so many options now. Which is a good thing, but I do like the local and community aspect of a terrestrial radio station, and the effort of that, and the effort of listening to it and the effort of doing it. I like effort-ful things.

What were the biggest challenges in the transition from writing about a subject to doing a film about it, many years later?

The biggest challenges were finding more archival footage and photos, tracking certain people down, convincing people to let me use some of their images in the film. And that just because I’m making a movie doesn’t mean that I have a ton of money and that I can afford to buy everything that we’re using. Financially it’s also really been unfun. I thought that I could make this for a lot less than it’s turned out to be.

Also, digitizing things that didn’t need to be digitized, or trying to make the footage, or using AI to make the footage look better. Which introduced all these like hallucinations. That was an expensive thing to learn that didn’t work. We subtracted all that footage out after we had to put in. So it was a very steep learning curve on many levels.

Are there any interesting stories that didn’t fit into the film?

There were certain things that were cut together that we didn’t use that were in the very first version. For the cleanliness of storytelling, we didn’t talk about being busted by the FCC, and then going back on the air. Just on holidays, when we thought the FCC wasn’t gonna be in the office. That was just too confusing to tell. We had cut together a sequence like that. And our signature campaign, like out in the community, like trying to get people to sign up and say we want this station, that we were gonna send in to the FCC somehow to like prove that we deserved to be on the air, like that would have done anything.

Once in a while, I wish I could bring the station back. It makes me sad that back in 2000, Congress was like, if you’ve ever run a pirate radio station, you can’t have a legit license. Because I feel like people now would have a lot of appreciation for it again. I know a lot of the DJs would like to do this again, and I just am in a different stage where I could never do this. Also the penalties for being a pirate are so much worse than they were back when I was doing it.

What are the plans for screening and distributing the film?

We’re still waiting to hear back from about fifteen different film festivals. We are gonna be screening at Long Island Music Hall of Fame, their first music documentary film festival on August 8. We’re going to Cleveland in September. I was just accepted into an Atlanta film festival.

Then distribution, which is really more important, we have offers. But I haven’t accepted any of them yet. I’m still considering them. Ideally, we want to be placed with a streamer, and then have another company who could do physical media. Then we’re looking at doing a soundtrack. None of that has been decided yet. There’s offers on the table, but no deals have been signed.

I am going to find this book and movie! I was a college radio DJ in the ’80s in Seattle (KCMU, now the mammoth KEXP), and briefly – like once or twice! – DJed on a Seattle pirate radio station called FUCC (somewhere in Capitol Hill). I wasn’t involved in the pirate except that I just wanted to DJ and play what I wanted to. Today, I DJ at a community non-profit in Port Townsend, WA* called KPTZ. For fun. And for supplying our rural community with something other than commercial radio. Now that CPB has been defunded, community stations are more important than ever. If you have one, support it! If you don’t have one, do what Sue did and create one!

* Across Puget Sound from Seattle