We’re half a century away from rock’s golden era—well, at least my favorite era of rock—and the reissues keep coming. There was no trouble filling up a Top Ten-and-then-some list for 2016, but there aren’t so many discoveries of previously unheard goodies these days, at least in my pile. The trend is more toward embellishment of previously available material into more definitive deluxe editions, with some overdue first-time-on-legitimate-CD issues of LPs that fans have long been clamoring to get back into print. There’s also a massive box of previously unreleased material from the prime of a major band (Pink Floyd) with the kind of hefty thoroughness that should be done for such acts, but seldom is.

Not that I hear many complaints from people who read this blog or other writing of mine, but the chronological scope of these reissues is narrow, though a few of them do fall outside of the mid-to-late- 1960s. This is, however, an honest list of my favorite 2016 reissues that I’ve heard. No doubt there were some I would have liked that I missed; contrary to some people’s belief, just because you’re a nice guy who’s written about this kind of stuff for a long time doesn’t mean you automatically get sent copies of everything you might want to hear. But if you care about rock history, you should find some items here you’ll want to know about, even if your concentration or specialties are different than mine.

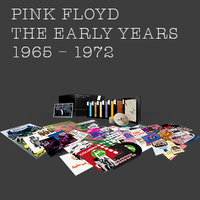

1. Pink Floyd, The Early Years 1965-1972 (Pink Floyd/Legacy). Selecting a monstrously large, expensive box by one of the biggest acts of all time doesn’t make for the most exotic #1 year-end choice. With a price tag hovering around $500, you can’t exactly exhort readers to rush out and buy it either. Yet this does have an enormous amount of rare, or at least off-the-beaten track, material from their pre-Dark Side of the Moon era. The package adds up to ten CDs and nine DVDs (the disc count goes up if you add the blu-rays, though these don’t have significant material not on the other discs). It doesn’t quite have everything of note you can’t find on their 1967-72 studio albums (more on that in a bit). But it has a great deal of it, often in better quality than you’ll find on bootlegs of the same cuts and clips.

Detailing and analyzing the contents in depth would take several thousand words minimum; go to the usual online sites for comprehensive track listings. For my own post, I’ll just note that while I have quite a bit of previously unofficial Floyd audio and video from this era, some of the audio and much of the video was entirely new to me. On the audio front, the most notable inclusions are their non-LP late-‘60s singles (previously reissued on numerous releases, but still not all that easy to find in total); six 1965 demos (previously released as a scarce limited edition) that aren’t that great, but are historically important as their first surviving recordings; and, most crucially, quite a few BBC sessions, many of which are really excellent.

Some of these, in fact, are arguably a match for, or even better than, the standard well known studio versions. The epic BBC rendition of “Interstellar Overdrive” from December 20, 1968—to give just one example—is both stupendous and quite different from the studio version, even if it (unlike many of the BBC cuts) isn’t quite hi-fi in fidelity. Other portions of the box are considerably less exciting, but sometimes—like the September 1969 live Amsterdam performance of their rather half-baked conceptual album-that-never-was “The Man”—carry notable historical weight.

Video-wise, while some of this (like their 1967-68 promo clips) has been heavily bootlegged, much of it hasn’t. The quality, both as far as the image and (to a lesser extent) the performance, is variable. But some of the footage is excellent, and most (if not quite all) of it worth a look for the serious Floyd fan, even if there are too many versions of songs like “Set the Control For the Heart of the Sun” should you pack your viewing into two or three days. It’s admirable how they kept finding new and interesting ways to do “Interstellar Overdrive” in particular. If ambitious pieces like “A Saucerful of Secrets” couldn’t avoid patches of tedium, they usually attacked such challenges with commendable fearlessness. Although the black-and-white footage of a near-full-length 1970 performance of “Atom Heart Mother” in Hyde Park is shaky, it’s certainly fascinating to see a large choir performing the piece with them live.

Could such a sizable collection possibly miss some worthwhile rarities? The answer, as it is for virtually all box sets of this magnitude, is yes. Even discounting the absence of several good circulating audio recordings of live early-‘70s concerts, the failure of Anthony Stern’s 1968 fifteen-minute avant-garde short film San Francisco to get included is a real loss, as its soundtrack is a hyper-jittery pre-record deal unreleased 1966 version of “Interstellar Overdrive.” There are plenty of Zabriskie Point soundtrack outtakes, but more have long been bootlegged. Their filmed-without-an-audience April 1970 performance (broadcast on San Francisco’s KQED public TV station) is missing some material shot for (but not used in) the program.

The absence of such items, however, will likely matter little or not at all even to most Floyd fans, as what’s here is abundant, of great historical interest, and often quite entertaining. Yet considering the scale and expense of this set, customers deserve more than the basic liner notes (by Mark Blake, author of the fine Floyd bio Comfortably Numb) here, although there’s a lot of neat memorabilia. Perhaps the three surviving Floyds could have contributed some quotes and memories with more details about this rare and oft-mysterious material, though it might not be easy to get them in the same room these days.

By the way, when I saw drummer Nick Mason in 2005 on the book tour for his memoir Inside Out: A Personal History of Pink Floyd, he was asked whether there was anything unreleased of interest in the vaults that might come out in the future. He was nonchalantly dismissive of the notion that anything was worth putting out—an absurd contention even then, before the existence of everything on this set was known. Whatever could have happened in the intervening decade to change his and the rest of Pink Floyd’s minds?

2. The Move: Move (three-CD expanded), Something Else from the Move (expanded), Shazam (two-CD expanded), Looking On (two-CD expanded) (Esoteric). A few times on this list, I’ve taken the liberty of grouping a few related releases into one entry. This is the most notable instance, as these four reissues take the Move’s first three LPs (and sole EP) and radically expand them in size with bonus tracks. The result is a definitive representation of most of their career, though it doesn’t include their final LP and singles (done for a different label) or a two-CD compilation of live 1969 Fillmore performances that came out a few years ago.

Although the Move are much better known in the US than they were in the late 1960s and early 1970s (due in part to Jeff Lynne and, if much more briefly, Roy Wood having gone on to the Electric Light Orchestra), they’re still not as widely known in the States as they should be. Aside from the Pretty Things, they were the best 1960s British rock group never to have a hit in the US. These CDs heap on a load of outtakes, demos, and (especially) BBC performances, some previously unreleased (though those of you who’ve kept up with other expanded editions and the Anthology 1966-1972 box will, alas, already have a great deal of this. They’re embellished with historical liner notes, a wealth of vintage photos, and (except for Something Else) mini-posters with reprints of articles from the UK press.

Space precludes a full examination of each CD; for that, you can consult my lengthy review of all four of them in issue #42 of Ugly Things. Let it just be said that if you haven’t heard or heard much of the Move, but you like the mid-to-late-‘60s work of the Beatles and the Who, these are highly recommended, as they combine some of the qualities of both bands with the added twist of Roy Wood’s eccentric but melodic songwriting. Move has their earliest and catchiest hits, as well as documenting the band in their poppiest (yet still pretty hard rocking phase); Something Else from the Move captures the band live at London’s Marquee club in 1968, and is surprisingly dominated by cover versions. Shazam finds them going into progressive rock-influenced epics (with some shorter songs thrown in), though not to the point of self-indulgence or sacrificing a catchy tune. Looking On, the only one of these albums recorded after Lynne joined, does sometimes verge on indulgent heavy progressive rock, though it retains some of their more songcraft-oriented elements. The wealth of BBC performances added to these CDs (Something Else excepted) include covers of quite a few songs the Move didn’t put on their regular releases, though these are usually ordinary in comparison to their studio performances of their original material.

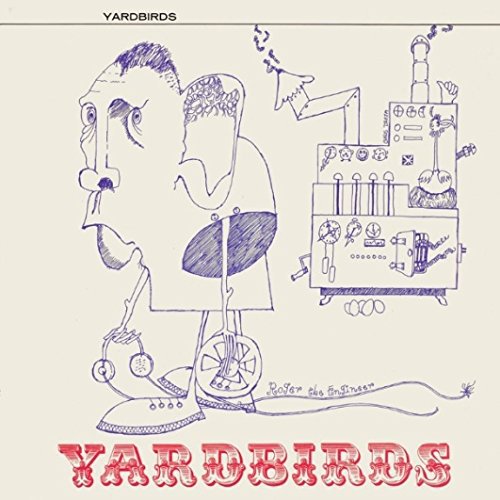

3. The Yardbirds, The Yardbirds (two-CD expanded) (Repertoire). If you’re a fan of the Yardbirds—nay, if you’re a serious fan of ‘60s rock in general—you’ve probably had this 1966 album for a long time, and perhaps in more than one edition. If so, this two-CD expanded edition of the original album doesn’t have a whole lot of (and possibly no) goodies here you haven’t previously heard. But this is the definitive edition of their only full studio LP with Jeff Beck in the lineup, and in fact their first studio LP, period (the one album they did with Eric Clapton was live). Frequently referred to as Roger the Engineer because of its ungainly cover drawing of engineer Roger Cameron (and titled Over, Under, Sideways, Down in its US edition, which subtracted two tracks), it was an uneven but often thrilling collection of tracks that blended middle eastern/Indian-influenced melodies, hard blues-rock, pseudo-Gregorian backing vocals, social commentary, and Beck’s unequaled mastery of sustain and distortion, sometimes in the same tune. Taken together, it was a building block of psychedelic music, though the quintet that made this album would soon alter with the departure of bassist/co-producer Paul Samwell-Smith and the entry of Jimmy Page.

This two-CD expansion has both the mono and stereo mixes, which sometimes differed radically, the mono mix of the weird-as-get-out instrumental “Hot House of Omagararshid” featuring a scorching Beck guitar solo missing from its stereo counterpart. It also has their incredible psychedelic single from later in 1966, “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” (with both Beck and Page on guitar), as well as its humdrum non-LP B-side “Psycho Daises” and the sole other track from the Beck-Page era, “Stroll On” (the rewrite of “Train Kept A-Rollin’” they played in the Blow Up film). There are also all five tracks used on Keith Relf’s rare 1966 singles (which were in a far more baroque folk-pop mold than the Yardbirds tracks on which he sang), and some alternate versions of songs from the 1966 LP of only marginal interest. Historical liner notes with comments from Samwell-Smith and drummer Jim McCarty top off the package. While it’s not my intention to turn this post into an ad for Ugly Things, issue #42 features a lengthy interview I conducted with Paul Samwell-Smith in 2016, including numerous comments about the Roger the Engineer album.

4. Judy Henske & Jerry Yester, Farewell Aldebaran (Omnivore). This has long been on the list of the most desirable psychedelic rarities never to gain legitimate CD reissue, which it finally did this summer, complete with historical liner notes and extra tracks. Originally issued on Frank Zappa’s Straight label in 1969, it’s an assortment of enigmatic songs with oddball imagery encompassing blues-rock, country-folk, satire, and early synthesizer experiments. There’s no better obscure album by early-‘60s folk revival veterans ending up as weird psychedelicists at the end of the decade. The five bonus cuts are just instrumental demos of some of the songs from the LP, but the rare pictures, graphics, handwritten lyrics, and period press release in the booklet are good surpluses. If I may, I think I can take some credit for revival of interest in this LP that finally led (almost twenty years later) to its CD reissue, as I included a chapter on Henske & Yester in my book Unknown Legends of Rock’n’Roll—now available in a radically expanded ebook edition, of course.

5. Fleetwood Mac, The Complete Unreleased BBC Anthology 1967-1968 (Albatross, bootleg). You can’t get this in stores, the quality is a little hissy, and there’s no annotation. So why does this rank so high? Because the music is largely very good—if I ranked these albums by how often I played them, it might place even higher. Quite a few Fleetwood Mac BBC recordings from the late 1960s and early 1970s (most with original lead guitarist/principal singer-songwriter Peter Green in the lineup) are on the two-CD Live at the BBC, but quite a few others remain unreleased. This features 19 of the early ones that didn’t make it onto Live at the BBC, and if the fidelity’s not quite optimal, in all cases it’s actually of an easily listenable standard. Of more importance, a lot of these songs were not only not on Live at the BBC, but not on any official Fleetwood Mac release.

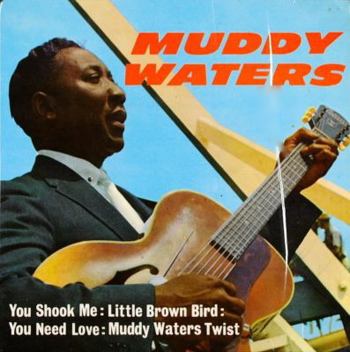

While some of this is routine blues or rock’n’roll oldies covers (including “Sheila,” “Bo Diddley,” and “Peggy Sue Got Married”), there are some dynamite blues cuts not included on their LPs, like B.B. King’s “Sweet Little Angel” and T-Bone Walker’s “Mean Old World.” Most interesting of all is an excellent version of Muddy Waters’s “You Need Love”—the same song (written by Willie Dixon) that provided the basis for Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love,” a year before that Zeppelin track was released (and a couple years after the Small Faces used it as the basis for “You Need Loving” on their first LP). Danny Kirwan takes lead vocal on the supremely haunting blues “Crazy for My Baby,” and while I’m not the biggest fan of Jeremy Spencer’s parodies, his “Psychedelic Send Up Number” is pretty funny and accurate (especially the lyric “I am here and you are there and we are all going nowhere”). It seems kind of unlikely this material will gain official release soon, but it should, with any sonic clean-up that can be applied without deadening the sound. For a fuller review of this CD, see my blogpost about it here.

6. The Beatles, Live at the Hollywood Bowl (Apple). How does the first CD issue of the only commercially available concert recording of the best rock act of all time not make #1 on a year-end list? Over-familiarity, perhaps. This was first issued on LP back on 1977; has never been hard to find used; and, despite the Beatles’ brilliance, isn’t all that great, in part because it wasn’t so well recorded. It couldn’t be well recorded considering the screaming at their shows and the concert recording technology of the time. It’s been remixed from the original multi-track tapes, but there really isn’t all that much you can do to make the source material sound much fuller or clearer. And while some might find it heretical, I don’t hear too much difference between this and the original LP.

Still, it’s an exciting document of their concerts—for it mixes tracks from 1964 and 1965 shows together—in the midst of Beatlemania. There are plenty of great songs and enthusiastic performances, even if the songs don’t veer radically from the studio versions (and, without exception, aren’t as good as those studio versions). And the CD does include new historical liner notes, as well as four bonus tracks (two apiece from 1964 and 1965 shows; one of these, “Baby’s in Black,” did previously come out on the 1996 Real Love CD single). Note, however, that three complete Hollywood bowl shows were recorded—August 23, 1964; August 29, 1965; and August 30, 1965. Yes, a mike failure meant that Paul McCartney’s vocals were missing from a few of the August 29, 1965 songs. But why not put out a double CD of all three shows—which have long been available in their entirety on bootleg—in the sequence the songs were performed?

7. The Mamas & the Papas, The Complete Singles: 50th Anniversary Collection (Real Gone). Is there much that’s previously unheard in any form on this double CD of Mamas & Papas singles that you won’t have if you’ve paid attention to the group’s releases, whether when they were active or since? No, and be aware that most of disc two has solo singles by Cass Elliot, John Phillips, and Denny Doherty that don’t measure up to the group efforts. Audiophiles note, however, that this anthology features original mono single mixes, some of whose components are significantly different than the ones used in the more commonly available versions.

Of more importance, however, disc one is simply extremely listenable—the best single-disc compilation of the Mamas & the Papas ever, in fact, even though it’s just half of this package. It has all the familiar hits, naturally. But it also has more quality B-sides and low-charting 45s than you might remember the group boasting, a few of which—“Got a Feelin’” and “Strange Young Girls” in particular—are on the level of their big hit singles. “For the Love of Ivy,” “Safe in My Garden,” “Somebody Groovy,” “Once Was a Time I Thought,” “Did You Ever Want to Cry,” “Glad to Be Unhappy,” “Too Late,” and “Midnight Voyage” aren’t far behind, and that’s almost an album’s worth of good non-hits right there. Also in its favor are lengthy liner notes with first-hand quotes from Michelle Phillips and producer Lou Adler, as well as a weird, wordlessly hummed 1969 Mama Cass solo single (“All for Me”) so obscure you can’t even call it up on Youtube.

8. Sandy Bull, Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo (Real Gone). In the early 1960s, it was virtually unprecedented for a musician to cut an album weaving together folk, jazz, blues, classical, gospel, and even a bit of electric rock’n’roll. Sandy Bull didn’t only do so over the course of his debut LP, 1963’s Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo. He also often fused different strands of folk, jazz, and world music within the same track, particularly on the groundbreaking cut that occupied all of side one, “Blend.” Lasting twenty-one minutes and fifty-one seconds, with jazz legend Billy Higgins accompanying Bull on drums, “Blend” was both mesmerizing and impossible to classify. In its length and improvisational feel (as well as Higgins’s drums), it drew from jazz; in Bull’s guitar style, elements of folk; and in its droning qualities and accelerating climax, aspects of middle eastern and Indian music. If side two’s four tracks were shorter, they were no less eclectic, encompassing interpretations of German composer Carl Orff, English Renaissance composer William Byrd, a Southern mountain tune, and a gospel song. Here’s hoping his yet better and more adventurous follow-up, 1965’s Inventions, will follow on CD soon. Incidentally, I did the liner notes for this CD, though I hope the ranking reflects where I would have listed it had I not written them.

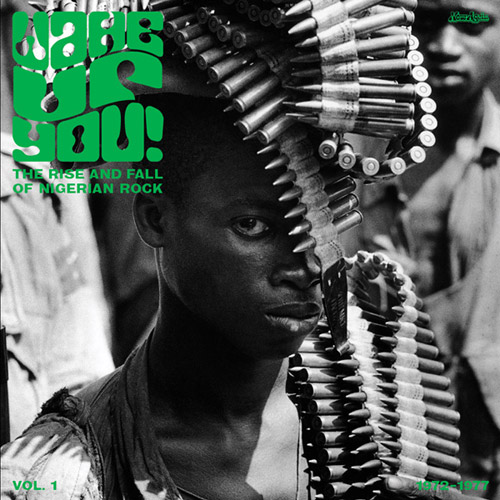

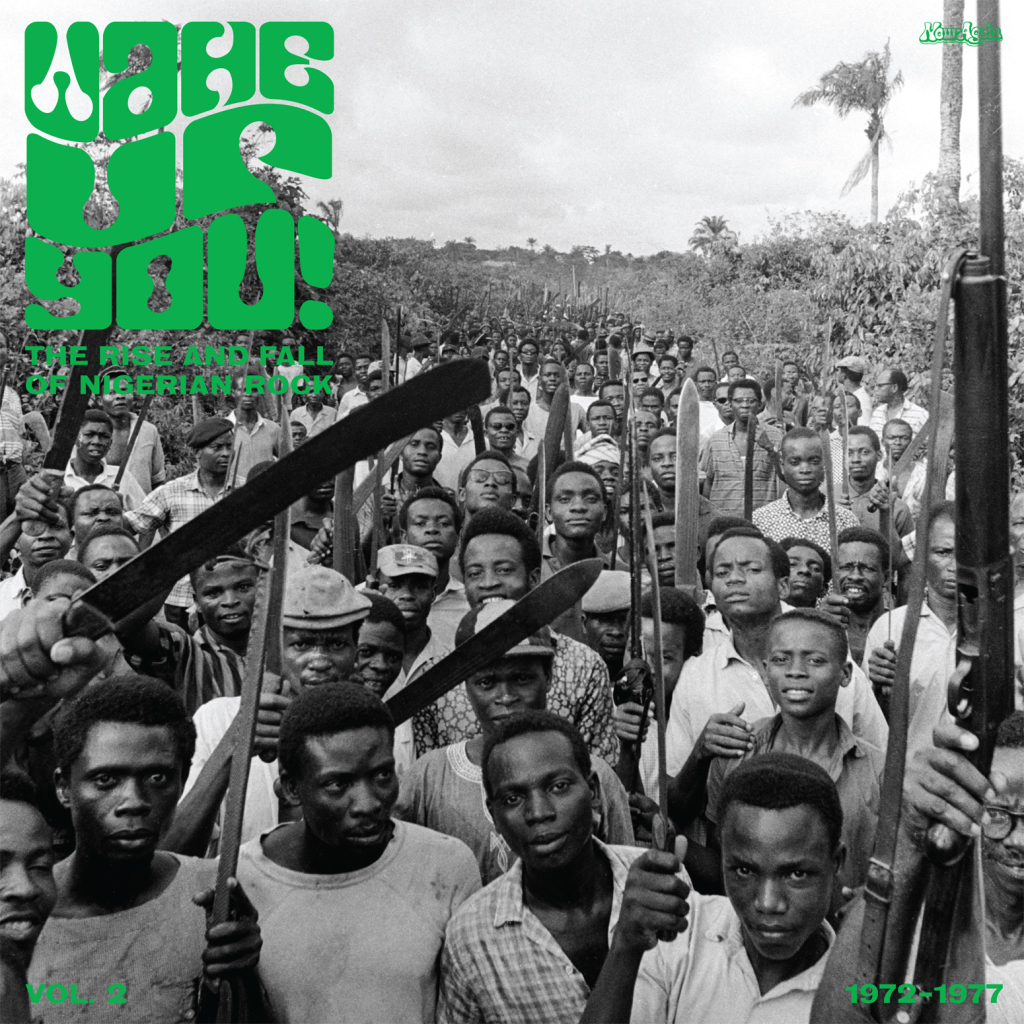

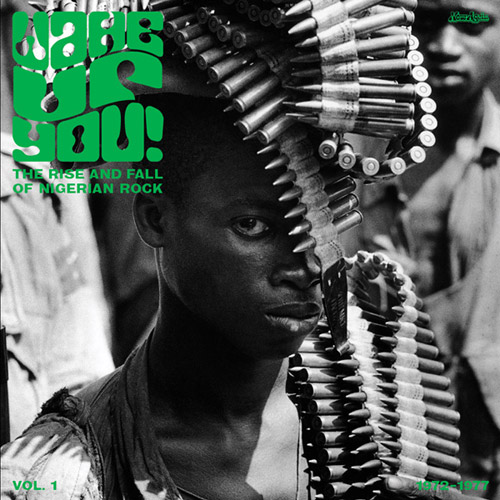

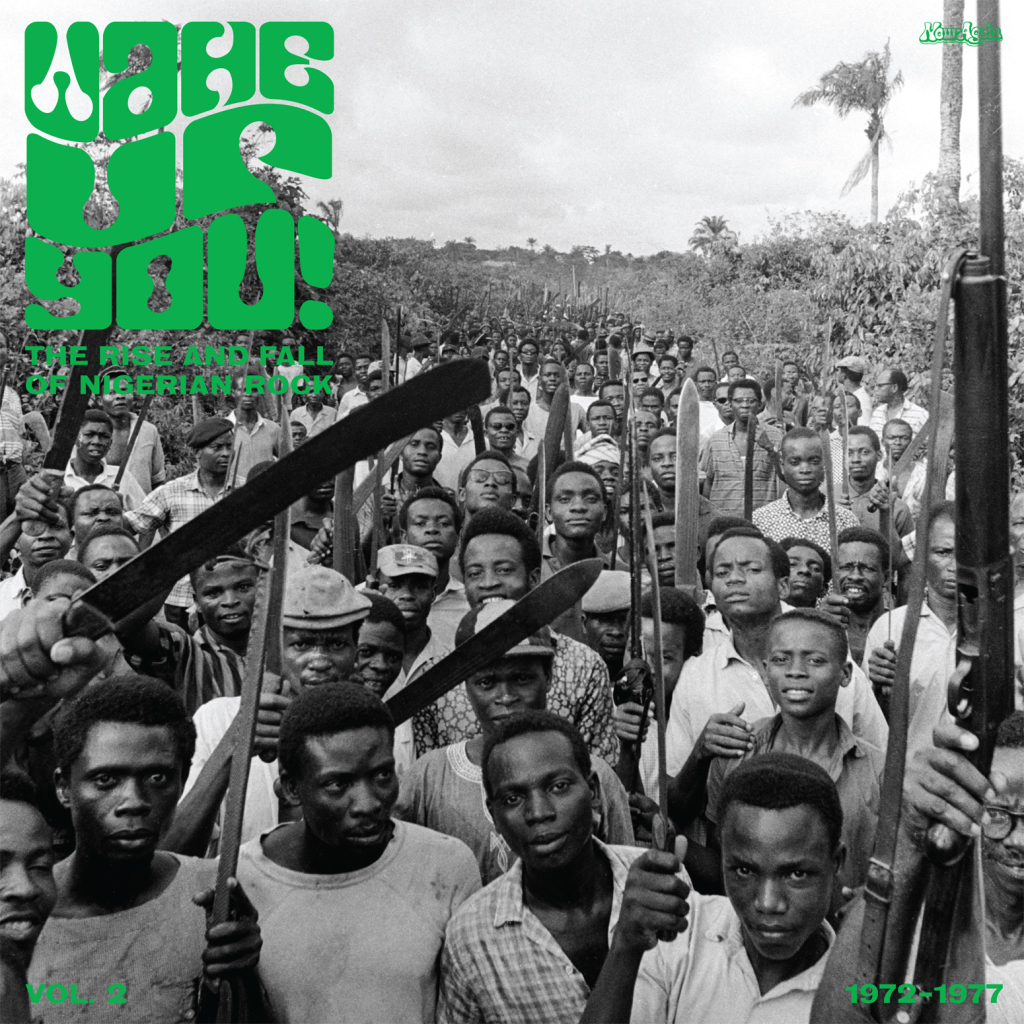

9. Wake Up You! The Rise and Fall of Nigerian Rock Vol. 1 & 2 (Now-Again). It’s amazing enough that Nigerian rock bands managed to form, endure, and (after the fighting was over, for the most part) record during and after the country’s 1967-1970 civil war. These two compilations collect rare tracks, virtually unheard outside of Africa beyond intensely specialist collectors, by Nigerian groups between 1971 and 1978. The music is an exotically awkward, at least to the ears of the Western collectors at which these US anthologies are targeted, mix of rock, soul, psych, and funk, sprinkled with a bit of highlife and other African influences. The label garage rock-soul-funk might apply, but it’s a little bit stranger than that, with lyrics that sometimes seem stream of consciousness without any attempt at being arty. Influences from American icons like James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, and Carlos Santana can be heard. But these Nigerian guys (they’re all guys) didn’t quite have the equipment or experience to replicate them, instead coming up with something more interesting than simple imitation.

Note that although these come packaged with extensive liner notes, the back cover blurb stating that these are “presented in two 100+ page books full of never-seen photos and the story of the best Nigerian rock bands told in vivid detail by musicologist and researcher Uchenna Ikonne” is a little misleading. These do indeed have interesting text and photos, but they don’t exactly add up to two books. Well over half of the text (and many of the photos) of the two volumes are identical, though each has some sections not in the other.

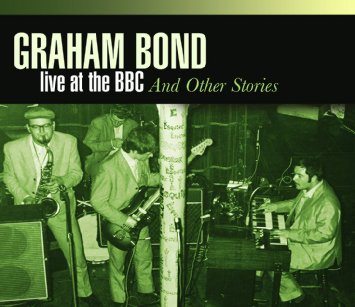

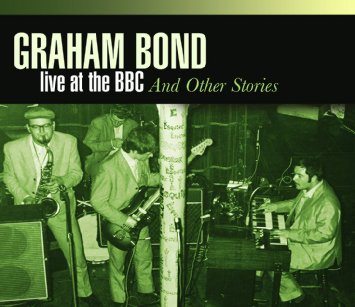

10. Graham Bond, Live at the BBC and Other Stories (Repertoire). It’s a testament both to the increased interest in demonic organist/singer Graham Bond’s music and the prolific body of work that survives that this four-CD set of 1962-1972 performances even exists. Most of its tracks are from the BBC, but some are taken from other live recordings, with a demo and rare studio releases on which Bond played thrown in too. Even if you have all his albums and the four-CD box of 1963-1967 material that Repertoire issued on Wade in the Water in 2012, you won’t have any of this. There are early-‘60s straight jazz recordings on which Bond played as part of the Don Rendell Quintet; 1963 BBC sessions (some backing singer Duffy Power) on which he and his group, with Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, started to make the move from jazz to tentative R&B; and three January 1966 tracks on which the transition from jazz to his idiosyncratic brand of growling, hard-hitting soul-jazz-inflected R&B/rock was complete, as well as some bits and pieces from 1966-1972 of marginal interest.

These account for three of the four discs, and if not for the fourth, this would be a kind of fill-in-the-blanks archival project for completists that couldn’t find a place on a year-end best-of roundup. Disc #3, however, would by itself earn a place on this countdown. Recorded by his short-lived Graham Bond Initiation outfit at two separate BBC sessions on January 31 and March 22 of 1970, it’s highlighted by a ferocious medley of two of his best compositions, “Walkin’ in the Park/I Want You,” and two equally galvanizing 13-minute interpretations of “Wade in the Water.” There are also two takes of one of his best post-Organization songs, “Love Is the Law,” as well as a couple others from his obscure, uneven late-‘60s US-recorded albums. The loose yet forceful “The World Soon Be Free” totally eclipses the comparatively anemic one on his Love Is the Law LP, and overall the ’70 sessions have a nearly mesmerizing blend of rock, blues, and hip jazz, with an aura that’s grim yet compelling. It’s Bond near his very best, playing and singing at a level he’d never again come close to in the four years remaining in his life.

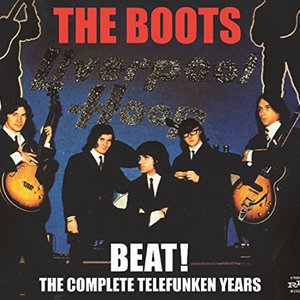

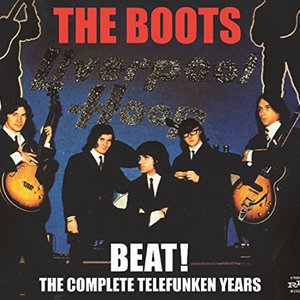

11. The Boots, Beat! The Complete Telefunken Years (RPM). Besides the Lords, the Boots were the best mid-‘60s German “beat” band. They were also the German band most capable at emulating the British R&B style. Given the relatively few competitors they had in both categories on the German scene, and the generally poor standard of pre-Krautrock German rock as a whole, you could be forgiven for judging the first two sentences of this paragraph as damnation with faint praise. But while they were gold and silver medalists without much formidable competition, the Boots did (rather like the Lords) make records that were genuinely fun, even if they’d never win awards in the originality department. This two-CD compilation has all of their 1965-1967 recordings, including both of their LPs, some non-LP singles, and some compilation appearances and outtakes.

Since the Boots for the most part covered songs recently recorded by British and American rock groups (or blues/R&B songs those bands covered) and wrote little of their own material, putting an idiosyncratic interpretive stamp on the material was necessary to make it noteworthy in any way whatsoever. This the Boots managed to do, with the help of Werner Krabbe’s mordant vocals and Ulli Grün’s funereal organ. And the Berlin band did have a feel for blues/R&B, whether on overdone standards like “Gloria” and “Dimples” or less clichéd choices like Cops & Robbers/The Pretty Things “You’ll Never Do It Baby” (here retitled “But You [sic] Never Do It, Babe”).

The non-blues/R&B tunes are in the minority, and might be disparaged by purists as too pop. Actually, however, these gave the Boots the chance to really ratchet up the haunted house factor that might have been their most distinguishing attribute. The Zombies’ great “Remember When I Loved Her” was eerie enough in its original guise; the Boots’ beyond-the-grave arrangement takes the despair of the original to the darkest corners of the cemetery. Similarly, the Shangri-Las’ “Remember (Walking in the Sand)” and the Walker Brothers’ “Another Tear Falls” were suitable vehicles for what we might call the Moody Boots, though not as striking as “Remember When I Loved Her.”

Disc one, dominated by their 1965 debut LP Here Are the Boots and early singles, is superior to disc two, given over mostly to the 1967 LP Beat with the Boots, on which they went in a far more soul-influenced direction. Even that includes a groovy organ-paced instrumental soul-jazz version of Mel Torme’s “Coming Home,” however. The best Boots material has been available on Bear Family’s Smash…! Boom…! Bang…! , but aside from its greater thoroughness, The Complete Telefunken Years has one more advantage. Unlike that Bear Family anthology, its liner notes are in English, summarizing the essentials of the Boots saga. That might be reason enough to make this the first comp of choice for English speakers, even if it’s more expensive.

12. Johnny Winter, Byrds Can’t Row Boats: The Unreleased Masters Collection 1965-1968 (Cicadelic). The numerous recordings Winter made in the mid-to-late 1960s a few years before he signed with Columbia have been around the block on quite a few compilations. These two-CD, 36-track collection gets points for thoroughness, even if less than half of it, despite the subtitle, is previously unreleased in any form (some of the other tracks are represented by previously unreleased mixes). To those wholly unacquainted with this period, it will come as a surprise to hear Winter trying out some folk-rock and psychedelia in addition to his usual blues-rock.

For those who favor those styles, those tracks will actually be the highlight of this compilation, particularly the excellent moody Byrds-styled folk-rocker “You Were Once a Man,” which wonders what a statue would think if he came to life today. The kind of nutso pseudo-surrealistic-Dylan “Avocado Green” is worth hearing too, as are the soul-rock tunes “Easy Lovin’ Girl” and “Comin’ Up Fast.” Much of the rest of this is the accomplished but rather routine blues-rock that Winter would make his main diet when he came to national attention. He does, however, turn in a surprisingly affecting cover of the Byrds’ “The World Turns All Around Her,” which (actually included here in two versions) is one of the highlights of this historically significant set.

13. Eclection, Eclection (Esoteric). Despite issuing just one self-titled album, Eclection’s history was too unusual to summarize in a two-paragraph review like this. (If you must, there’s a full chapter on the group in my expanded edition of Unknown Legends of Rock’n’Roll.) Suffice it to note that although they were based in the UK, just one of the quintet came from the UK, the others hailing from Norway, Canada, and Australia. Their 1968 LP, one of the more interesting obscure folk-rock albums of the period, actually sounded more Californian than British. Its harmonies, slightly orchestrated production, and song construction strongly recalled early Jefferson Airplane, the Mamas & the Papas, and the Seekers, but the band split before doing any additional albums that might have carved a more distinct identity.

This record’s been reissued on CD before; I did the liner notes for that edition, in fact. But this has the significant advantage of adding three non-LP tracks from late-‘60s singles, one of them featuring a different woman singer (Dorris Henderson) than everything else they released, on which Kerrilee Male handled the female vocals. The sound they achieved is more pleasing than the actual songs, to be honest, but that sound is a very pleasing one. This (like the Clear Light reissue listed below) would have ranked higher had the core album around which this CD is based not already been long available without the extras.

14. Clear Light, Clear Light (Big Beat). Nearly twenty years ago, I described Clear Light as sounding “like the Elektra Records roster (the Doors, Tim Buckley, Love) being tossed into a blender.” I’m aware Clear Light cultists would scream in protest that the one-liner was unfair, or even that they weren’t at all derivative of those acts. Still, I stand by that assessment, though I’ll also point out that it’s not a criticism. Clear Light might not have been nearly as original as the Doors, Tim Buckley, or Love, all of whom at various points worked with the producer of Clear Light’s self-titled 1967 album, Paul Rothchild. But the period Elektra psychedelic sound of their LP is appealing, even if I found it a bit generic.

The Clear Light album has been previously issued on CD, but this Big Beat edition is easily the best, as it adds lengthy historical liner notes; the non-LP B-side “She’s Ready to Be Free”; the pre-Clear Light single by the Brain Train, from whom Clear Light evolved; and, most importantly, four previously unreleased outtakes. The outtakes aren’t too great or memorable, but add to the picture of this interesting psychedelic one-shot group (though it’s not a complete one, as two surviving tracks from their abandoned second album were judged of too low fidelity to be included). The best Clear Light track, included on here and on the original LP, remains their most over-the-top one: a gonzo six-minute version of Tom Paxton’s “Mr. Blue,” which transforms the rather tame folk tune into an epic psychedelic horror show.

15. The Tomcats, Running at Shadows: The Spanish Recordings 1965-66 (RPM). Despite the subtitle, the Tomcats were not a Spanish group, nor were most of their recordings in the Spanish language. Instead, they were one of the many hopeful British R&B/rock groups springing up in the wake of the Rolling Stones, somehow ending up in Spain, where they performed and got to record four EPs in the mid-1960s. Known (if at all) for evolving into the late-‘60s British psychedelic group July (who recorded one album that has a cult following), they never even released discs in their native UK. This compilation, esoteric even by British Invasion collector standards, has all the tracks from those Spanish EPs, as well as a non-EP track from a film soundtrack and a few demos from the Second Thoughts, a few of whose members went on to play in the Tomcats.

The preceding paragraph is probably enough to put off listeners who want something in the way of name recognition before taking a chance on obscure material. But this is a pretty enjoyable release, if wildly uneven and not at all as original, distinctive, or creative as the bands (like the Rolling Stones and Pretty Things) whose paths they generally followed. The folk-poppy Spanish-language tunes done British R&B-style are genuinely strange, but also genuinely, at times atomically energetic. They do an unexpectedly terrific rock/R&B cover of Reverend Gary Davis’s country blues standard “Cocaine” that’s quite different from the prototype. The title track is a very good folk-rock-cum-British Invasion original that’s the only strong hint of development of a personality of their own. Much of the rest is generic early British R&B or uninspiring faithful covers of big mid-‘60s British and US hits, though even some of those are appealing. But the highlights make this worth investigating for British Invasion fanatics, though you have to be pretty fanatical to plunge this deep.

16. The Beach Boys, Becoming the Beach Boys: The Complete Hite & Dorinda Morgan Sessions (Omnivore). Before the Beach Boys signed to Capitol Records, they had a local hit with “Surfin’,” and recorded a few other tracks in late 1961 and early 1962 for producer Hite Morgan. These, and some outtakes from those sessions, have been on some other albums dating back many years. This double CD, however, is the most thorough exhumation of those sessions by far, including not just all nine songs they recorded at these sessions (also including an early version of “Surfin’ Safari”), but also many unreleased alternate takes of those tunes. It adds up to 63 tracks in all, augmented by lengthy historical liner notes (by Jim Murphy, author of the recent book Becoming the Beach Boys, 1961-1963), cool rare graphics of tape boxes, and vintage ads/record labels.

This, even more than some of the other entries on this list that dig into a very specialized corner of an artist’s career, is a “not for everybody” release. The many multiple takes of each song are presented in separate groups of nine, meaning you’ll hear run-throughs of the same song over and over again for nine consecutive stretches. It’s kind of like hearing a completist bootleg of surviving sessions (and there are many of those for the Beach Boys’ Capitol recordings, particularly in the 21-volume Unsurpassed Masters series), except this release is legitimate.

For scholars, however, it’s still interesting to hear the embryonic Beach Boys working out their harmonies, even if the alternate versions aren’t too different from each other, and the instrumental backing is so rudimentary as to border on the minimal. It’s also surprising, admittedly with the benefit of more than half a century of hindsight, that the Beach Boys had trouble getting a record deal after the release of “Surfin’.” Even at this stage, it’s obvious they had talent (particularly in the vocal department, and particularly in their harmonies and Brian Wilson’s leads). It’s also obvious, again in hindsight, that even so early on, they didn’t sound like anyone else, and should have been a group worth investing in—as Capitol did.

17. Tim Buckley, Lady, Give Me Your Key: The Unissued 1967 Solo Acoustic Sessions (Light in the Attic). How does previously unreleased material from the prime of a significant artist rank low on this list? It’s not because I feel he’s overrated. Indeed, I wrote a big chapter on Tim Buckley in my Urban Spacemen: Overlooked Innovators & Eccentric Visionaries of ‘60s Rock book. And almost half of these 13 tracks were re-recorded for his best album, Goodbye and Hello.

Perhaps inadvertently, however, these rather bare-bones demos illustrate just how much Buckley’s songs benefited from baroque-folk-rock studio production. In this rather naked state, they tend to sound rather alike and run into each other, as they do on another archival release on which Buckley plays backed by just his acoustic guitar, Live at the Folklore Center, NYC—March 6, 1967. Plus the songs that he didn’t put on his studio albums (although different versions of a couple have shown up on other archival reissues) don’t make one question the decisions to omit them in favor of stronger compositions.

The above two paragraphs might be seem like a harsher dismissal than intended. This is of considerable historical importance; Buckley’s singing is very good; and some of the numbers redone for Goodbye and Hello, particularly “No Man Can Find the War” (one of the finest protest songs ever), radiate obvious strength even in this unadorned condition. With excellent liner notes incorporating a wealth of comments from producer Jerry Yester and frequent Buckley co-writer Larry Beckett, it’s of great value to the serious Tim Buckley fan. It can’t stand on the level of Buckley’s best material and performances, however.

18. John Lee Hooker, The Modern, Chess & Veejay Singles Collection 1949-62 (Acrobat). I don’t get as many random unsolicited cool things in the mail as some people think. But sometimes items do show up that I probably wouldn’t have come across otherwise, like this four-CD, 101-song John Lee Hooker compilation. Now, as great as Hooker was, you couldn’t say he made the most diverse recordings, many of his sides then and later sounding pretty similar to each other in their earthy boogie stomp. (The last song on CD two, perhaps aptly, is titled “Too Much Boogie.”) So this might not be the kind of set you want to play in sequence too often, even if you’re a blues nut. It’s also not comprehensive, sticking to tracks recorded for three labels, though he cut a fair number for other companies (like Specialty, for whom he recorded more than a dozen in the mid-‘50s). Nor does it have the singles he did under a number of colorful assumed names, from The Boogie Man to the who’s-fooling-who John Lee Booker.

Still, what’s here has the cream of his best recordings, including his top classics “I’m in the Mood,” “Crawlin’ King Snake,” “Boom Boom,” “Dimples,” “I’m Mad Again,” “Maudie,” “Boogie Chillun,” and “Louise.” (The last song might not be one of his core classics, but it’s familiar to rock audiences as the Yardbirds did a version on their 1964 live LP, though it might not have been based on Hooker’s, as John Lee wasn’t the only one to record it.) While some purists find some of the later recordings on this set inferior to his earlier ones due to their use of more electricity and full bands, I actually find many of these among his very best (and, in the case of “Boom Boom” and “Dimples,” his most famous). Sure, there are some routine tunes here, and the approach can veer on monotony. But rather like early Johnny Cash box sets are okay to hear all at once if you’re in the right mood, and in the mood for songs that don’t vary all that much, this is general quality listening that formed some essential building blocks of mid-twentieth century popular music.

19. Jesse Fuller, Working on the Railroad (Mississippi/Secret Seven). This six-song, ten-inch vinyl reissue is of considerable historical importance. Cut just north of Berkeley, California in El Cerrito in 1954, these were the first recordings by major folk-blues singer and one-man band Jesse Fuller, including his first version of the well-known “San Francisco Bay Blues.” But it’s also musically impressive as well. I’m not much for most recordings from the very early folk revival, of which these just about qualify, being geared more toward specialized folk fans than the commercial market. However, these recordings are rich and full, with some pretty amazing instrumental work (more so on guitar than kazoo) considering it’s all by one guy. Most of these songs (“San Francisco Bay Blues,” “John Henry,” “Lining Up the Tracks,” “Railroad Work Song”) would be overdone in the ensuing ten years of the folk revival. Yet as these are the first or among the first versions, they have a powerful freshness most interpretations lack.

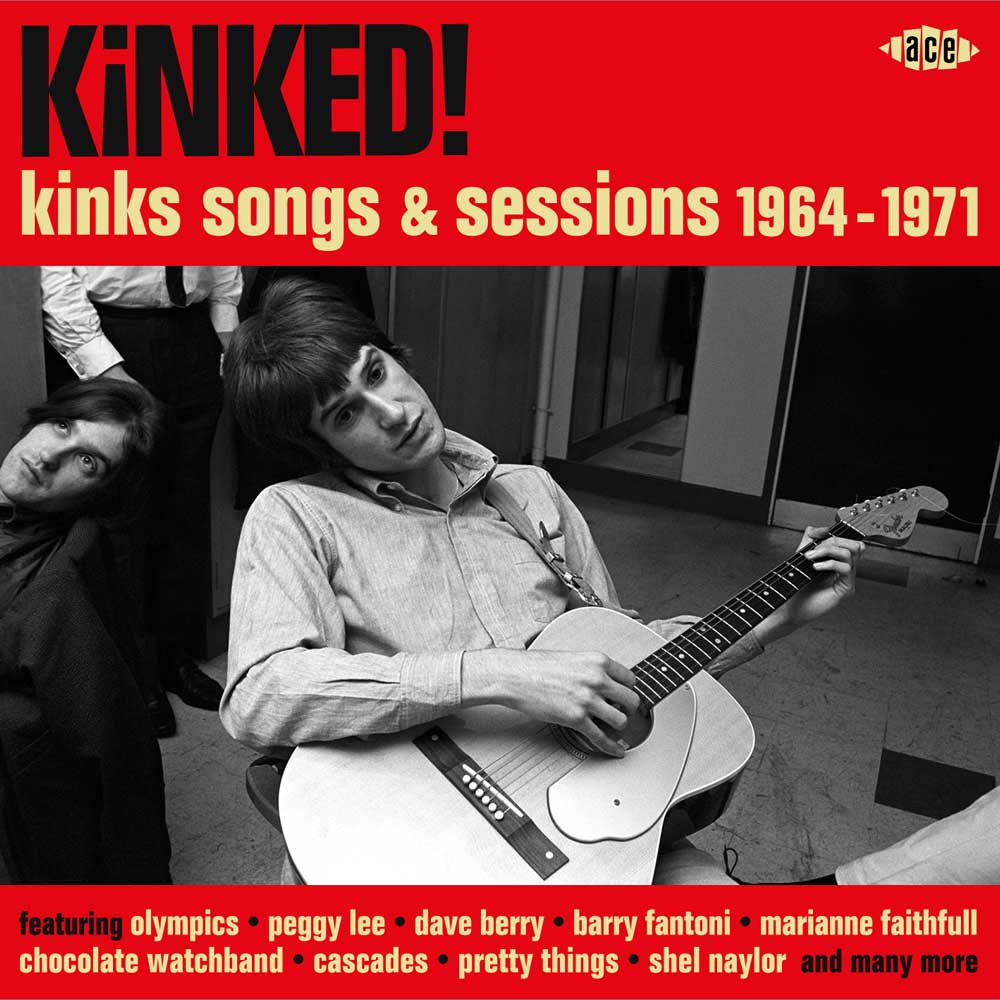

20. Various Artists, Kinked! Kinks Songs & Sessions 1964-1971 (Ace). Sometimes a record makes a list, at least my list, because of its historical significance instead of its musical merit. Yeah, maybe that’s not fair, but if that’s your stance, take heart that at least this is at the bottom. You can’t tell from the title, but this is a compilation of Kinks covers, not actually tracks by the Kinks themselves. What makes this special is that it focuses on, and rounds up most of, the songs Ray Davies (and, in one instance, Dave Davies) wrote, but the Kinks did not release, though some Kinks BBC versions/outtakes/demos of such tunes showed up many years later on some archival compilations. As with the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, there were a fair amount of such items the Kinks “gave away,” though none of them were hits, with the arguable exception of Dave Berry’s “This Strange Effect,” a mild UK hit (and not a hit at all in the US), but a huge hit in Holland and Belgium. Some of these rarities have been hard to find in either their original versions or on reissues, and this anthology does hardcore Kinks fans a great favor by collecting most of them in one place. The CD’s rounded out by uncommon or offbeat covers of songs the Kinks released first, like Marianne Faithfull’s “Rosy, Won’t You Please Come Home” and Duster Bennett’s “Act Nice and Gentle.”

All the same, there’s not a single outstanding cut among these 26 tracks—and nothing even on the order of, say, Billy J. Kramer’s version of Lennon-McCartney’s “Bad to Me” or the Toggery Five’s cover of the Keith Richards-Andrew Oldham composition “I’d Much Rather Be with the Boys,” to cite a couple Beatles/Stones giveaways. There are some better-than-average ones, like Berry’s “This Strange Effect,” the Pretty Things” “A House in the Country” (which has a verse not in the Kinks’ version), the John Schroder Orchestra’s wistful instrumental “The Virgin Soldiers March,” the Orchids’ energetic girl group take on “I’ve Got That Feeling” (whose release predated the Kinks’ recording of the song by about half a year), and the Thoughts’ “All Night Stand” (here represented by a previously unissued alternate take). But the most highly sought after rarities—those that don’t exist in any Kinks version—are surprisingly bland. Nonetheless, it fills in a notable gap in the Kinks (or at least Kinks-related discography), its value upped by compiler Alec Palao’s customarily thorough and informative liner notes. It would be nice if this paved the way for similarly expert comps of giveaways by the Beatles, Stones, Who, and others, but I wouldn’t bet on such collections appearing soon.

And an “historical mention” to:

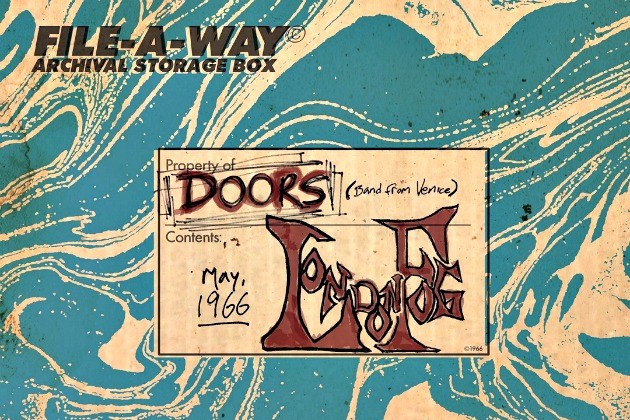

21. The Doors, London Fog 1966 (Rhino/Bright Midnight Archives). Here’s another “historical significance” pick, yet one in which the historical significance outweighs the musical quality even more. This recently unearthed tape of a May 1966 performance at the London Fog on Sunset Strip is the earliest circulating live recording of the Doors, and the first of any kind with the quartet that made their famous albums. It’s not terrible; the sound is pretty good for an audience tape, though Jim Morrison’s vocals are a little hollow. But they sound a bit like an average, at times even plodding white blues-rock band, a little as if they’re trying to be an American Rolling Stones with a prominent organist.

Five of the seven songs are covers, and while they hold interest as uncommon tunes in the Doors’ catalog, their interpretations of “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” Little Richard’s “Lucille,” Wilson Pickett’s “Don’t Fight It,” and “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” (the last with Ray Manzarek on vocals) aren’t scintillating. It’s surprising to hear them do the original “You Make Me Real” at this early date, as it didn’t show up on their studio releases until 1970’s Morrison Hotel, though the version here is inferior. Only on “Strange Days” do you hear the hypnotic eeriness that would be one of the Doors’ most arresting trademarks.

It’s a little surprising that they’d cut their classic debut album (which didn’t include any of the songs here) just a little more than three months later, as Manzarek excepted, the members are some ways off their peak. Morrison’s vocals are almost there, though it’s odd to hear him shout-plead with the audience to dance at a couple points, in line with the semi-bar band they still were. Robbie Krieger’s guitar isn’t as assertive as it would become. Most surprisingly, John Densmore’s drumming—superb on their first LP and thereafter—is clunky enough that had I been told there was a sub or it was by a guy he replaced, I would have believed it. Unfortunately, another reel with “The End” taped by the same friend who taped the other performances is missing. And while this package includes some memorabilia and both CD and ten-inch LP versions of the material, $49.98 is too high a list price.